Dead man talking: Richard Dorrough’s chilling triple murder confession

After turning a gun on himself at a Perth shooting range, Richard Dorrough admitted he’d killed three people. His likely victims were easy for us to find – so why didn’t police catch him?

There was nothing about the man who walked into the Lone Ranges Shooting Complex that Saturday, August 9, 2014, to suggest he was about to make a confession. “He was just another customer,” says Bradley Yates, who runs the gun range in Belmont, Perth, just south of the Swan River. He’d been in once or twice before. Each time, he’d paid his money. He’d handed over his ID when the staff working on reception asked him for it. The former Navy sailor still wore his hair cut short, the way he did during his brief stint in the military.

Since then Richard Dorrough, 37, had worked as a sheet metal fabricator, a welder and a commercial diver. He lived with his fiancée, Joy, and their children in Byford on the city’s south-east margin, where lots of young families went looking for big blocks at reasonable prices. He was “quiet”, “normal”, “nice”, “supportive”, according to those who knew him. So far, so ordinary. Even after Dorrough used the pistol that he hired at Lone Ranges to take his own life, Yates didn’t think too much about him.

Then, a few days later, a parcel arrived at the Byford home, addressed to Joy. It contained an exercise book filled with Dorrough’s handwriting. Only one line has ever been made public: “I did kill three times. It’s the hardest thing to live with while trying to become a witness.” He provided no names, no dates, no places.

Yates only heard about the confession later, after the police announced an investigation. Maybe his conscience got the better of him, Yates thought. “You know, he was his own judge, he was his own jury and facilitated through us his own execution.” But even then, you’re still left wondering what he meant by “trying to become a witness”. And who were the three people he had killed?

It’s easy to find one of Dorrough’s likely victims. So easy, you wonder why the police didn’t catch him. On the night of January 13, 1997, Dorrough was drinking in a bar in Broome where his Navy patrol boat, HMAS Geelong, had docked. He was 19, two years younger than the woman drinking with him, Sara-Lee Davey, a bright, fun-loving receptionist. She came from the remote community of Ardyaloon, or One Arm Point, a two-and-a-half hour drive north of Broome through the red desert, to where it meets the blue ocean. “It’s God’s country. It’s beautiful. If you come there, you’ll know,” says Sara-Lee’s mother Irene, a Bardi elder. Sara-Lee, her youngest daughter, was confident and trusting. “A young person that loved family, making friends and meeting people.”

Sara-Lee had travelled to Broome with her family, choosing to stay there with friends while her parents continued further south, another full day’s drive along the wild, empty coastline to Karratha. In the early hours of January 14, she took a taxi with Dorrough to the long wharf where HMAS Geelong was moored. According to the sailor on watch, Dean Fraser, Dorrough approached, saying he wanted to take Sara-Lee on board. Fraser refused. Dorrough responded, “I’ll just go and f..k her at the end of the wharf”, according to Fraser, who watched the two walk off together, out of sight.

Time passed. Then Dorrough returned alone. “I asked him, ‘Where’s the girl?’”, says Fraser. “He said that she’d already left.” Fraser pauses. He knew this must be wrong. For Sara-Lee to leave, she would have had to walk right past where he was standing on guard duty. “I knew she hadn’t left,” Fraser continues. But he didn’t push it. It was dark. “There’s always a possibility I could have missed her.”

Dorrough had some long scratches on his face, Fraser noticed – marks he hadn’t seen when the two men had spoken earlier that night. Later, when questioned by police investigating Sara-Lee’s disappearance, Fraser told them about the scratches. They didn’t seem to think it was important. “They asked a question, I give an answer, there was no follow-up to that answer,” he says. “I always felt like not enough questions were asked.”

Irene Davey also feels that questions were not asked. By the time she and her husband returned to Broome, expecting to meet up with Sara-Lee, the Navy boat had left town. Two months later, long after she reported her daughter missing, police did speak to the boat’s crew in Darwin. But no attempt was made to search Dorrough’s quarters or do forensic tests on his clothing. During those early days and weeks, then months, Irene kept calling the police, asking if they knew what had happened to her daughter. Years passed and Irene says no one told her that Sara-Lee had been seen at the wharf. No one told her about another witness, who had been fishing on the wharf that morning and spoke to police within weeks of her daughter’s disappearance, reporting that he heard a woman yelling “What the f..k are you doing?” and “Get off me”, followed by a loud, ungodly, frightened scream.

Today there is still no official explanation of what happened to Sara-Lee. A coroner found the cause of death to be “unascertained”. Her body has never been recovered. She remains an unsolved disappearance, one of hundreds of cold cases stretching back decades on the books of the WA police. Detective Superintendent Rod Wilde, from the force’s Special Crime Division, says there could have been more emphasis placed on Dorrough after witnesses reported seeing him with Sara-Lee at the bar in Broome. “And perhaps searches and some seizing around his clothing and in searching of items there that might have forensically linked him,” Wilde continues. “There were things that we could have done and perhaps should have done, in hindsight, differently, that would lead to a different outcome.” Instead, there was confusion at the time, with police chasing claims that Sara-Lee was seen alive after the date her family reported her missing. These have subsequently been discounted. Asked what he thinks happened, knowing what he knows now, Wilde says simply, “I think [Dorrough] killed her.”

Dorrough’s second victim also doesn’t take a lot offinding, because he was charged – and then released – over her murder. About 8.15pm on Friday, November 6, 1998, Rachael Campbell walked down the stairs of the two-storey apartment she shared with her mum and daughter in Lilyfield, inner-west Sydney. Rachael was wearing bright red lipstick, says her daughter, Taila. “She was gorgeous.”

Taila, who was four back then, says her mum used to smell of cigarettes and patchouli oil. She was always listening to Cat Stevens. That night, Taila was staying up late to watch their favourite movie, A Little Princess. Rachael said she had to go out. She promised to be back in time to watch the end of the film together.

Rachael’s body was found the next morning, naked and wrapped in a bedsheet in the car park of St Joseph’s Catholic Church in Rosebery, a few kilometres from her apartment. She had been stabbed in the neck several times. The police also found a bite mark on her left forearm. Twisted up inside the sheet were used condoms and a single, bloodstained $50 note. Rachael’s death was described by media as “another streetwalker stalker murder” and Rachael as a “hooker” with a heroin addiction. Reducing her mum to a caricature like this wasn’t fair or honest, Taila says. “She was my entire world. She was a good person, you know? I couldn’t imagine a better mother.”

Police focused on the fact that Rachael did some sex work, interviewing and taking DNA swabs from several men suspected of violent crimes against other sex workers. None matched the unidentified DNA found in those condoms and on Rachael’s body. Without a match, her death remained unsolved, like Sara-Lee’s in Broome – although, just as with Sara-Lee’s death, the police did speak to Dorrough.

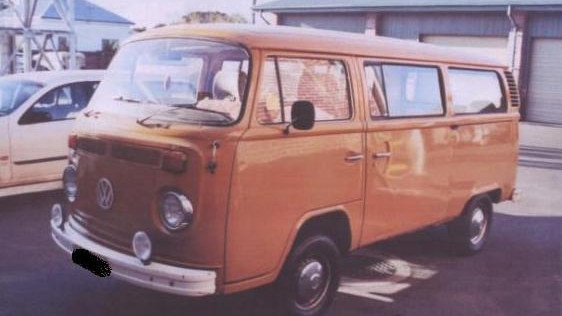

They suspected that whoever killed Rachael had picked her up on the street in a station wagon or van that had a mattress in it. Dorrough had bought a Kombi van with a mattress in it four months before Rachael’s murder. That weekend it was parked on the street outside his apartment, which was a few minutes’ drive from where Rachael’s body was discovered. The next day, quite by chance, police knocked on Dorrough’s door, asking routine questions about another, unrelated murder. Dorrough couldn’t help them. Soon after, he left Sydney, driving the Kombi north over the state border. By this time the cops in Western Australia had questioned him about the disappearance of Sara-Lee but had not taken his DNA. Police in NSW had found DNA with Rachael’s body but didn’t know who it belonged to.

Dorrough would soon be questioned by a third police force, this time in the state where he settled after leaving Sydney: Queensland. That interview took place after a hit-and-run he was involved in. On July 18, 1999, eight months after Rachael’s murder, he sat in Bundaberg police station explaining how he had been in his Kombi van outside a local nightclub with a woman he knew only as Kym. “We were just chatting in the front seat,” Dorrough said. He claimed another man walked up and started an argument, then attacked him. “I didn’t really decide [to run him over],” he told police. “It just sorta happened.”

The other man, David O’Connell, woke up in hospital with a broken leg, cracked vertebrae, deep cuts to his face and the skin shredded from his hands. Dorrough was charged with attempted murder but later pleaded guilty to the lesser charge of grievous bodily harm. The judge was sympathetic and sent him to prison for a year only. In prison, Dorrough’s DNA was taken.

Back then, each state kept its own record of DNA samples taken from crime scenes and from individual criminals. There was no way to compare records between states, and even when the first national database of criminal DNA was established in June 2001 – two and a half years after Rachael’s murder – samples weren’t all matched automatically by computer. To find a match, police had to revisit unsolved cases, reopening the files and requesting that any outstanding, unidentified DNA exhibits be compared against those on the national database. With Rachael’s murder, that didn’t happen. Not for the best part of a decade.

Jo Kamira tells a story about the weekend of her younger sister Rachael’s murder, which she says sums up the early police response. When Rachael didn’t make it home to watch A Little Princess as she’d promised, Kamira says their mother waited until the next morning, then called police. She gave them a description: Rachael had Maori heritage; she’d been doing sex work to feed a heroin addiction. The police said to call back the next day if she didn’t show up. Their mum did so but seemed, again, to get nowhere. Kamira suspected the police weren’t taking her sister’s disappearance seriously.

That might seem unfounded, except that Kamira was a former Australian Federal Police detective. She’d worked in the drugs squad and later been put in charge of equity and diversity. So, on the Sunday, Kamira called the local police near where Rachael had been living, introducing herself as a former detective sergeant. “I said, ‘My sister’s gone missing. My mother’s reported it twice. She keeps getting fobbed off.’” She gave them a description of her sister. The officer said they would send detectives to meet with Rachael’s mother. At this point Rachael had been lying in the morgue for two days. Kamira says it felt like nobody had looked at her that closely.

Today Kamira lives in Canberra, a long stone’s throw from the AFP headquarters. She believes police treat some cases differently, especially in their early stages when deciding whether to launch a full murder investigation. Some don’t get the proper attention, says Kamira. Sometimes it’s when the victim is an intravenous drug user. Or a sex worker. Or Aboriginal. The families are told their loved ones have gone walkabout and maybe they will show up. “When you look at how many Indigenous women have gone missing or have been murdered and there’s been very little done about it… Very, very little.”

Speak to the police who investigated Sara-Lee’s disappearance or Rachael’s murder and they all say they worked it as hard as they knew how to. But they also admit that more could have been done, especially in those crucial early hours and days when evidence is most fresh and before memories have faded.

The failure to catch Dorrough meant he was free to kill again. Kamira thinks there was a pattern to the women he selected: Sara-Lee was Aboriginal, Rachael was Maori, Kym – the woman sitting with Dorrough in his Kombi when he ran over O’Connell in Queensland – was Aboriginal. Each of them was a chance meeting: Sara-Lee inside a bar, Rachael at work, Kym on her own outside a nightclub. In Kym’s case, O’Connell intervened. Dorrough’s guilty plea to that attack meant there was never any trial, so Kym’s version of what happened was never heard in court. When approached today and told what happened to the two other women before her, she replies: “I guess I’m lucky.”

Eventually, the police did catch Dorrough over Rachael’s murder. In November 2008, a fresh review of the forensic evidence matched DNA discovered with her body to that taken from Dorrough in prison. In January 2009, three NSW police detectives flew to Perth and arrested him at work. Despite Kamira’s criticism of the cops’ slow start in the first few days following Rachael’s death, her family have nothing but praise for how they handled everything that followed.

Dorrough was extradited to Sydney and put on trial for Rachael’s murder a year later, in April 2010. The jury were told about the DNA match, and the bite mark, which seemed a close fit for his teeth. But they weren’t told everything about him, says Rachael’s brother, Phil Campbell. The jury were not told why Dorrough spent time in prison in Queensland – just that it was a traffic incident. They weren’t told anything about Sara-Lee’s disappearance. That’s the way the courts work, to prevent the jury being prejudiced against the defendant. But, says Campbell, it meant that the defence could present Dorrough as a good guy – a former Navy sailor, an average Aussie bloke. In contrast, the papers were still calling his sister Rachael a “Sydney prostitute”.

“They couldn’t relate to her,” says Campbell. Having heard the evidence presented to them, it took the jury four hours and 10 minutes to come to their decision. They found Dorrough not guilty.

In the months after Dorrough took his own life, West Australian police had another look at Sara-Lee’s disappearance. In October 2015, more than a year later, State Crime assistant commissioner Michelle Fyfe held a press conference saying they were “seeking the public’s assistance regarding Dorrough’s movements across Australia and New Zealand over the past 20 years”.

Fyfe would not discuss his confession to having killed three people. Or to admit explicitly that they were looking for unsolved murders. Instead, she said, “We are looking at serious offences. We don’t know specifically what he was responsible for or if there are any unsolved crimes at all that he was responsible for. We are in possession of some information that indicates he may be.”

Fyfe also refused to concede, when asked by a reporter, that police had waited too long after Dorrough’s death to appeal for information when “it would have brought, perhaps, closure to these families earlier” if they could name his victims. “Investigative strategies are investigative strategies,” she replied. “[The] decision to go with a public awareness strategy is part of any investigative strategy. The decision has been taken to do it now.” That press conference was the last time any Australian police force publicly attempted to find Dorrough’s victims. If Sara-Lee and Rachael are, in fact, two of the three people he confessed to killing – which has never been officially confirmed – no law enforcement agency seems able to name his third victim.

But there are names out there. Part of the challenge is that there are so many names; there were more than 800 unsolved homicides in Australia during Dorrough’s lifetime, and more than 400 missing people. You can try to sieve the numbers down, using the pattern identified by Rachael’s sister, Jo Kamira: women of Aboriginal or Maori heritage who were killed or went missing in states where Dorrough was known to be living. Each of these assumptions could be wrong. But even if they’re not, the number of potential victims left unsifted is disturbing.

Privately, detectives in NSW and Western Australia talk about the unsolved murder of a Maori woman in Sydney as possibly being linked to Dorrough, although they say the evidence isn’t there to be certain. And, as these detectives admit, finding the third victim is not a priority for any Australian police force. Dorrough’s dead. He is no threat to others. Yes, there’s a family out there who don’t know what happened to their mother, sister or daughter, but the police have only got so many resources, so many hours in any one day; they have to prioritise those cases where the killer is still living.

Which feels tragic. Like Dorrough won – that his penultimate act of confessing to three murders but choosing not to name the victims might end up being decisive. And that feels wrong, particularly when his fiancée Joy, the woman who received his written confession after his death, says there are clues. That Dorrough used to tell her how easy it would be to hide a body.

Dorrough once talked about hiding a body in the water, Joy says (she asked not to have her surname published). Sara-Lee was last seen at the Broome wharf, built out into the ocean. Another time, Dorrough said something about a body wrapped in a sheet in a car park – like Rachael was. Joy says she didn’t understand these cryptic conversations with Dorrough at the time. It’s only looking back, like when he told her: “When a person goes missing and the person that’s done it is really good at it, they will never find where they are.”

“What do you mean?” Joy says she asked him.

“Oh, they’ll never find her,” he repeated.

At the time Joy says she thought, “Find who?” Now she wonders if it wasn’t his third victim.

Joy can also help explain what Dorrough meant by saying killing was “the hardest thing to live with while trying to become a witness”. She says they’d joined a community of Jehovah’s Witnesses while living in Perth. Dorrough was looking forward to his baptism. But, one day, he discovered being baptised would first mean making a confession of his past sins. Joy says Dorrough asked the Jehovah’s Witnesses what might happen if he’d done something that was really bad. Bad enough that he could go to jail for it. Would they report him? They said they would.

Joy asked Dorrough why he asked that question. What was he hiding? “He just went quiet.”

In the end, Dorrough got to choose how he made his confession, what it included, what it left out and what would happen to him after. He got to end the story his way, but his victims didn’t get the same choice.

The best chance of taking back that narrative may now be beyond the reach of those police forces that have investigated Dorrough in WA, NSW and Queensland. It may be closer to the home of Jo Kamira, Rachael’s sister in Canberra, who lives a few minutes’ drive from her old employers in the AFP headquarters – and from the federal parliament. Later this year, a senate committee will begin investigating the cases Kamira says don’t get enough attention: missing and murdered Indigenous women and children. The inquiry was proposed by Greens senator for WA Dorinda Cox, a Yamatji Noongar woman whose cousin was violently killed three years ago. The motion was co-signed by Lidia Thorpe, Greens senator for Victoria and a DjabWurrung Gunnai Gunditjmara woman whose cousin was also killed. The committee’s first task is to invite submissions and then hold public hearings to establish just how many cases like this are out there.

“There’s a long line of women who have either gone missing or been murdered [and] police have not taken any action,” says Senator Cox, who is a former police officer. “It’s quite phenomenal when you think about this, the sheer volume of them. There are women that have been missing for 20 years or so and no one’s bothered to look for them.”

Cox says she’s determined to start looking for these women. Dorrough’s third victim may well be among those names the committee uncovers.

Bloodguilt: the Many Deaths of Richard Dorrough by Dan Box and Kate Wild will be released on Audible on Tuesday.

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout