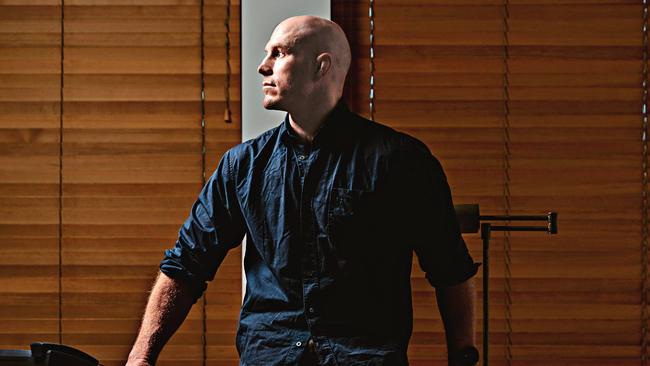

David Pocock on defying stereotypes, rugby, religion, and holding the balance of power in the Senate

Former Wallaby David Pocock keeps a journal, meditates and practises gratitude: good luck trying to stereotype the ACT senator. As a player he was never afraid to speak his mind, but politics has been a baptism of fire.

He tries to start the day with some quiet contemplation.

In the early morning hush, while the sensible people of Canberra are still snoozing, David Pocock can often be found writing in his journal, meditating or generally practising gratitude because “it’s easy to forget how good a lot of us have it”. Next, there’s that body, still as strong and angular as a concrete block but it needs daily work because you don’t play professional rugby union for 15 years and bounce out of bed without a twinge. It’s not just Pocock’s body that requires this physical workout, his mind needs it too. He once punished himself in obsessively unhealthy ways but these days he knows how to keep this side of his personality in check and his morning mind-and-body routine is part of it. “An older, wiser person once asked me, ‘What do you need to do to be well?’’’ he says in his quiet, considered way. “We all know that there are things that we do that make us feel much better.”

And so anyone walking along the deep sandy banks of the Murrumbidgee River near Canberra at dawn on Fridays will find their local senator stripped to his shorts and gathered with some mates for a commando-style workout that makes the usual politician’s jog around Lake Burley Griffin look decidedly tepid. Rocks are hauled overhead and slammed to the ground or lodged on shoulders for uphill sprints; bodies crawl and worm and leap through the sand. There’s jumps and squats and on it goes, nonstop, for 45 minutes until the reward: an ice bath in the tree-lined river.

The former ACT Brumbies star, who played 83 test matches and three world cups for the Wallabies, goes hard in these sessions even though there’s no match to prepare for now. Life as a politician is gruelling in a different way. As the first independent to break the major party stranglehold in one of the ACT’s two upper house spots at last May’s election, Pocock barely had time to settle into his red leather seat when he was called to action as a balance of power senator. “It’s been a wild ride,’’ he says.

He’s almost 35 and this is his first real job outside sport and his own charitable organisations, but those called to negotiate with Pocock soon learnt not to underestimate him. Pragmatic and outcome-focused are some of the words Canberra insiders use to describe their early dealings with him. Inexperienced but willing to listen; highly engaged and committed. Some suggest the Government has manipulated him, that he’s naive, though none have gone as far as fellow senator Pauline Hanson’s “doormat Dave’’ line.

“It’s an easy stereotype, the football player who is out of his depth,’’ Pocock says with a grin that doesn’t quite engage his blue eyes. It’s the sort of look I can imagine him flashing an opponent when he ripped the ball from their grip and sprinted for the try line. His wife Emma was watching on at an event last year when a heckler started up in the crowd. “And he got this little half smile on his face,” she recalls. “I’d seen that on the field if the opposition was ever heckling him. He found it energising and motivating. It’s a skill to bring to politics because you do come under a lot of pressure and people will say things about you.”

Anyway, good luck trying to stereotype Pocock. He was one of the world’s greatest rugby players who devoured feminist texts and Jungian psychology in his spare time, who read theology as he explored his conservative Christian faith. The strong man who was openly vulnerable, revealing his battle with an eating disorder, body image and obsessive training habits. The fearsome warrior on the field who took a stand against hyper-masculinity off it. The quietly spoken introvert who has long spoken out about environmental causes, marriage equality and social justice at a time when sportspeople were expected to shut up and play.

If you think Australian cricket captain Pat Cummins is too vocal about issues like climate change, it was Pocock who led the way. The rugby star wouldn’t just speak, he would act, once stopping play to complain to a referee after hearing homophobic slurs. He blacked out sponsors’ names on his boots because he couldn’t be sure of ethical supply lines and was arrested in 2014 after chaining himself to equipment at a coal mine protest. His wedding to Emma wasn’t off limits, either – they delayed their formal nuptials until marriage was legally available to all.

Of course his “keep politics out of sport” critics dismiss all this as sanctimonious grandstanding but anyone who knows Pocock understands he is a man of deep convictions who has long held that professional athletes should use their platform in a responsible way. “It’s the right thing to do,’’ was his common refrain when called upon to explain his actions. You can imagine the angst among football administrators left dealing with the fallout.

“Speaking out, he was less concerned about the public response and more concerned about whether it was affecting his teammates. That was the lens he would look at it through,’’ Emma says now. Former Wallabies and ACT Brumbies skipper Stephen Moore says Pocock was always respectful of his teammates as he grappled with the need to speak his mind. “For the most part I’ve always had huge respect for his courage in speaking up for what he believes in,’’ Moore says. “Where it becomes complex is in a team environment, that’s always a fine line. For the most part Dave got that right, [but] there were probably a few occasions where he maybe compromised his teammates and the organisation that was employing him. I never liked to restrict anyone having a personal view but it is tricky because you have an organisation that has sponsors and affiliations that you have to consider all the time.”

In a life lived creating headlines on and off the field, his political allies and opponents have a wealth of information to bring to their understanding of David Pocock the politician. For a reserved man he has been unusually transparent – ACT voters can hardly complain they didn’t know what they were getting. He’s been nothing if not consistent.

But is there something to be learnt from the way he approached rugby? Moore speaks of his incredible discipline in preparing for games. Dan McKellar, his coach at the Brumbies, has watched Pocock’s progression with interest. “He was a rugby player who was the ultimate professional, as tough as nails and didn’t back down from a challenge,’’ McKellar says. “And I’m pretty sure that’s exactly how he will approach his political career.”

In a darkened room at the Australian National University we’re staring at the guts of a quantum computer, its multi-coloured wires spilling out in seemingly random tangles. Pocock puts the non-scientists in the room out of our misery with a request to keep it simple, lifting his hands to his shaven head to convey a mind explosion. Dr Andrew Horsley, a co-founder of Quantum Brilliance, breaks it down but there’s only so much information that can be conveyed in 20 minutes, and with a handshake and a group photograph we’re back in Pocock’s electric car. He’s only halfway through a speed-dating session with Canberra small businesses that’s taken him into the world of cyber security, carbon accounting and hospital waste management. There’s still wildlife drones, space satellites and geospatial intelligence to explore before he can drop his notepad in his office at Parliament House and think about his day – and the crammed political year ahead.

The hallways outside his office are quiet when I visit but come Monday they’ll be swarming with politicians, advisers and lobbyists for the sitting week. Many have already found their way to his door or arranged a quick meet – Pocock the footballer still has star power. His key Senate vote provides extra lustre.

He’s taken on the role with the same quiet purpose with which he approached rugby, though he hasn’t yet acquired the polish of others in this building. He doesn’t walk into a room with the assured thrust of an experienced politician and he thinks before speaking, often creating long silences, as if he’s set his own verbal emissions target. No need to add to the hot air over Canberra. While some find these pauses discomfiting – “You never know what he’s thinking” – others point out that when you’re not talking, you’re listening. And his supporters say this is one of his strengths: taking in information, and running it past his trusted confidants. Everyone speaks of the influence of his whip-smart wife Emma; they’re a solid team.

Unusually for a politician, Pocock is not considered a grandstander. “And he doesn’t walk into a meeting telling you what he thinks he knows,’’ says one observer. His old football mates say he was the same in his playing days – no point saying something if it doesn’t need saying. There’s no amusing Lambie-esque turns of phrase and unlike some of the Senate’s more colourful characters he’s unlikely to trouble the speaker, only once being called out for unparliamentary language in a speech on climate change when he used the word “bullshit’’.

His old coach McKellar says Pocock was always humble and quiet in the way he went about his rugby. “He wasn’t out the front telling jokes or being loud or making it all about him. He went about his job really quietly.” Emma describes his manner as unimposing. “At times I’ve had people say he’s a bit aloof or standoffish but I just think that reserved quality is quite jarring to what we usually expect from blokes. I’ve always found it a really appealing part of him as a person,’’ she says.

He first saw his future wife at a vigil for the homeless in 2009 in Perth, where Pocock was playing with the Western Force. Emma too had grown up in a conservative Christian home and she was studying women’s studies. Pocock was reading widely (Gandhi, Martin Luther King Jr, and Catholic priest and peace activist John Dear), and they bonded over books. “When I met him he’d just finished reading everything that Desmond Tutu had ever written and he was going through a big Stoics phase. So he was not your average 21-year-old,’’ Emma says.

Their first joint read was Mere Discipleship by Lee C. Camp, a book exploring the biblical Christian message. “I hadn’t met too many people my age who were exploring similar things so it was pretty exciting,” Pocock wrote in his autobiography Openside, released in 2011 when he was just 22. He goes on to describe a collage he did with Emma, which featured a picture of Gandhi. “And underneath the drawing of him is one of my favourite quotes: ‘One needs to be slow to form convictions but once formed they must be defended against the heaviest odds’.”

During this time in Perth he was still grappling with a stress-related eating disorder he’d developed when his family moved to Australia in 2002 with all their belongings stuffed in a few suitcases. They were among the white farmers driven from their properties in the violent mayhem of the Zimbabwean government’s land reform program that was meant to redress colonial-era land grabs. Pocock has written of the intimidation and fear of that time, the farm workers and white farmers in their district being beaten and murdered. “On one occasion we had to flee the farm after being tipped off that there was a group of militia heading our way.’’ These were hard early lessons in inequality and social justice, dispossession and messy real-life political consequences and they left a deep imprint on the young Pocock. “Growing up in Zimbabwe, politics affected every part of your life,’’ he once observed.

Aged 14 and safe with his family in Brisbane, where he attended Anglican Church Grammar School, he became irrationally strict about what he ate; he worried about taking in any fats and developed a ‘‘very skewed idea of my body image and what I looked like”.

“In hindsight my diet was not about being healthy but was something I had a lot of control over and I went to such extremes to maintain that control,’’ he wrote. With the help of a psychologist he learnt that extreme dieting and exercise gave him a sense of control and certainty, a likely response to the fear and powerlessness he’d experienced in Zimbabwe. He turned to the writings of Carl Jung and Jungian psychoanalyst James Hollis to try to make sense of things, and Emma helped him deal with irrational thoughts that badgered him when he became stressed.

So how has he been dealing with the pressures of political life? Have the demons been vanquished? “I don’t think it ever goes,’’ he says after a long silence. “You can try to outgrow some of it and have better ways of thinking about it and put other things in your day-to-day to deal with it.” He’s talking of his morning journalling, his exercise regimen, meditation, being out in nature. His views on religion have changed over time and he no longer describes himself as religious. “I’m definitely spiritual… there’s so much mystery and I’m OK with that.”

He likens the pressure of parliament to the high-performance environment of elite sport. “In terms of the pressure, rugby was really helpful, having that almost weekly test where you had to perform and you were open to scrutiny regardless of what else was going on. You run on the field and it’s time to turn it on.”

At various times in his rugby career Pocock was touted as a future politician, and not just because of his activism. “He has a presence and an aura about him,” McKellar once said. “When he walks into the dressing sheds, him being there makes everyone a better player.’’

Pocock had been approached to run for politics in the past but a call from proACT – a “voices of” community movement that gave rise to a suite of teal candidates targeting Liberal MPs – caused him to reconsider. After retiring from rugby in 2020 he’d completed his Masters of Sustainable Agriculture; with brother Steve he started a conservation program, the Rangelands Regeneration Trust, in Zimbabwe, where he has retained strong links. He also co-founded with Emma (a former adviser to Greens Senator Sarah Hanson-Young) FrontRunners, an organisation for athletes and sporting bodies who want action on climate change.

When the call came he wasn’t at a loose end as such but the time seemed right to think about politics and his newfound backers thought they could see a pathway to victory.

With more than 2000 volunteers and a strong local profile, both major parties were worried. In the event Labor’s Katy Gallagher was re-elected and Pocock ousted the Liberals’ Zed Seselja. The senate makeup means that the Labor government now needs the Greens and two other crossbenchers to pass legislation opposed by the Coalition. Their first port of call is often Pocock and the Jacqui Lambie Network, thrusting the new senator into a powerful position, although he quickly renounced the kingmaker tag. “It’s certainly not a mantle I seek; instead I’d prefer to be a peace broker,’’ Pocock noted in his maiden speech.

It’s nine months since the election when we meet in February and he looks comfortable enough striding the corridors of Parliament House where his pale shaved head and muscular form, which never looks quite comfortable in a suit, makes him hard to miss. He’s front page news today in the local daily The Canberra Times under the headline “Pocock’s War Chest”. Political donation disclosures are out and the David Pocock Party received nearly $1.8m in donations, including $856,382 from Simon Holmes à Court’s Climate 200.

He’s not worried by the story: “I welcome the conversations that it’s generated. Let’s talk about it.” Climate 200’s money came from more than 11,000 individual donors, he points out, and he’s on the record from the outset calling for reforms to the donations process, with real-time disclosures a first step. Did he knock back many donations? “Yes, we knocked back quite a few. Most trading companies, property developers and also EV companies. I knew that if I got in, and while I think we should be transitioning to electric vehicles, I didn’t want to be compromised by taking that money and then having a hand in EV policy.’’

From the outside he was cynical about politics but he says being on the inside has changed that somewhat. “Being in the senate is so much more collegiate than it appears from the outside. There are genuinely good people in there. People have different views of the world and ideas about how different problems can be solved, but a lot are genuinely trying to represent their states and territories.”

Pocock has already ticked off some of the issues on his hit list. He helped push through the Territory Rights Bill that will allow the ACT and Northern Territory to pass voluntary assisted dying legislation. The national anti-corruption commission bill was a good step but he’s disappointed that public hearings will only be held in exceptional circumstances. “There was a deal between major parties and we can’t do anything about it,’’ he sighs.

He supported the government’s 43 per cent emissions target legislation after securing agreement for greater accountability and transparency. And with the Greens his vote was crucial to the Government’s energy plan, although he later confessed to being surprised when The Australian revealed that, as a consequence, nearly $450m of taxpayer funds would be used to compensate mining giant Rio Tinto, a move he described as perverse. “The compensation is done by a regulation and we quizzed the department on what they thought it would come to and I think we don’t really know the total,’’ he says now. “We knew there would be some compensation for contracts that had been locked in [but] I don’t know where the figure of $450m for Rio Tinto came from.”

Nevertheless, it was used to suggest he’d been screwed by the government. “People are going to find stuff to have a crack at you and that’s fine,’’ he says. “You’re trying to make the best decisions on the information that you have available and it was pretty clear when it came to gas on the east coast that something had to be done.’’

He’s quickly learning the art of compromise, using his power where he can to push through amendments to increase transparency and accountability. Labor’s landmark industrial relations reforms came down to his vote and after fierce lobbying from all sides he negotiated a deal that included an annual independent review of welfare payments including JobSeeker. He supported the Government’s safeguard mechanism, which is intended to reduce carbon emissions from the country’s biggest polluters, even though he wants bolder reform.

Before this vote, I’d asked him: can you live with supporting legislation that will likely allow for new gas and coal projects? There was a long silence and he took a deep breath: “Um… clearly we need more climate ambition, we’re leaving it late… It’s about pushing the major parties to act rather than listen to vested interests whose interest is not to act in the short term.’’ He thought about it some more. “People didn’t vote for me to go in there and blow things up. I want to be constructive and push really hard and be pragmatic – you have to get outcomes.”

He says he has met with mining groups and understands the country can’t turn off fossil fuels tomorrow. “One of the big issues around the Australian conversation around climate change is because it’s so heavily politicised, if you’re speaking about speeding up the transition and moving away from fossil fuels people just assume that you’re anti-mining.

“A lot of these mining companies are transitioning to electric, hydrogen, all these sorts of things, and that is often lost from the conversation. The world is going to want a lot of green steel. We’ve got the iron ore, we’ve got the electricity with solar and wind – you combine those two and that’s a massive industry for us. The mining companies are going to be a big part of that going forward.’’

He could settle in for a long discussion on this topic because he gets frustrated with the media soundbite. He’s more of a long-form guy. “With a lot of policy it’s hard to communicate the details, and politicians on all sides use that. They know they can sell a really simple message that doesn’t tell the whole story.’’

Is he, as some suggest, an easy dance partner for the Government? “Labor is in government, most of the policy that comes through is theirs, so it’s about working to try to make it better or get amendments,” he says. That doesn’t mean he’s in lockstep with the Government. If treasurer Jim Chalmers wants to ask, Pocock has a few ideas about ways to find the money to afford more social and affordable housing and lift JobSeeker payments.

“It’s about priorities. Yes, the budget is tight, but at the same time we’ve seen both major parties not want to budge on $250bn of stage three tax cuts. We’ve seen $368bn committed to submarines. We still give fossil fuel companies, despite them making record profits, four or so billion in diesel fuel rebates. There’s plenty of money in there if we’re going to be frank about finding money and prioritising it. That’s before we even start to dig into capital gains tax discounts on investment properties. These are things we need to have frank conversations about without the fearmongering.”

An impossibly cute orphaned wombat is swaddled like a baby and tucked into Pocock’s arm, its long-clawed front feet working free to try to grasp at the giant hand that’s holding its bottle. He chats to the carers from ACT Wildlife about the scourge of mange and habitat loss, as one of his advisers takes notes. Information gleaned from visits to small businesses or community groups can lead to a quiet word with a relevant minister or department head, a question asked in estimates or committees. This visibility is necessary – unlike the six-year tenure of other senators, the territory senators must go to the polls every federal election.

These meetings also put him in touch with experts and he draws heavily on them when making decisions. As a new politician with no established party infrastructure around him Pocock has had to find his own processes for considering complex legislation and has assembled a strong team to advise him.

“A lot of people have offered their expertise and knowledge and so I’ve tried to consult as widely as possible,’’ he says. “I have a few people I trust to bounce ideas off and I have a great team. But in many ways it’s talking to people in the community, seeing what they care about. My commitment to the people of the ACT is that for each piece of legislation I’ll look at it on its merits and use whatever leverage I have to get good outcomes.”

The baby wombat is stealing the show when a carer brings out a squawking baby chough and Pocock’s eyes light up. As a kid he was a keen birdwatcher and walking round Canberra you often see his eyes drawn up to the trees. The wombat is handed back and he’s over with the bird as his adviser looks at the clock. Dave and birds; this could take a while.

He looks relaxed but there’s a lot going on in his head. He’s “fully supportive” of the Voice referendum, and he’s holding out on whether he’ll support the Government’s $10bn Housing Australia Future Fund. He’s looking at environment laws, transitioning to renewables, truth in political advertising and stricter rules around political donations. In a week’s time he’ll lodge a notice of motion to establish a national inquiry into the management of feral horses in the Australian Alps.

But standing here in a wildlife carer’s backyard, with a wallaby joey peering out of a cloth bag that’s slung around his neck, the baby chough cheeping away and the wombats squirming in their wraps, he looks to have all the time in the world until an adviser leans in. “Dave, we’ve got to keep moving.”

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout