‘Dad suffered … and I was charged with a crime’: Tracey Curro’s elder abuse nightmare

In the midst of a bitter family stoush, the former 60 Minutes reporter’s father was left unbathed, unfed, had his money taken and his will changed. It’s a horror scenario playing out across Australia.

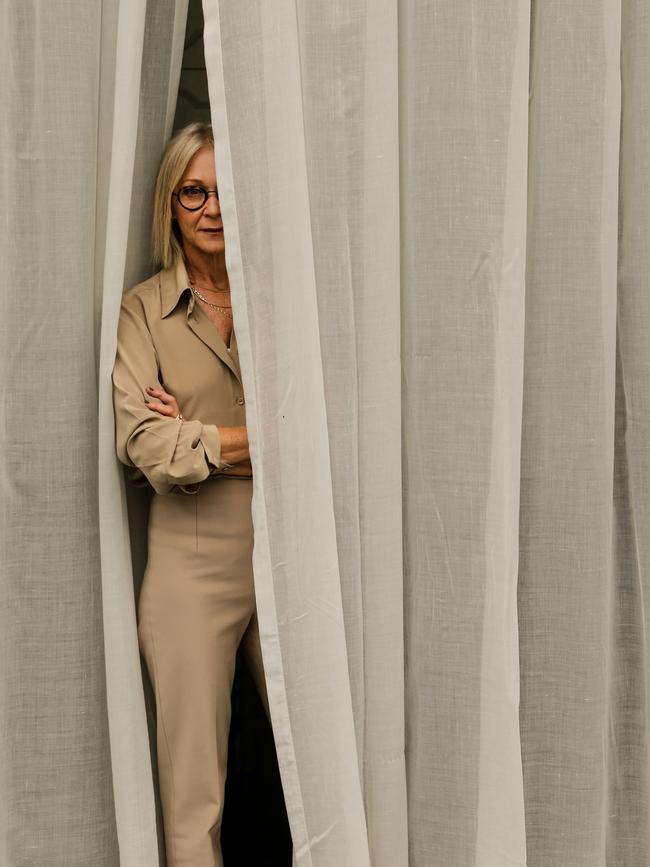

It happened, quietly, in May. Queensland Police finally closed the darkest chapter of Tracey Curro’s life. An assault charge that had been hurled against her in September last year – accompanied by the headline flashing across Australia, “Ex 60 Minutes reporter charged with assault” – had been dropped with very little fanfare. In the end, police had simply found “no evidence” to support the claim. But for Curro, the news was seismic. The trumped-up assault charge, and the sensational, gut-punch headline it produced, had been part of a much bigger nightmare. Her good name was collateral damage in a battle that she and her sister Peta had fought on behalf of their dying father, Phillip. The protagonists in the saga were extended family members and an ex-partner-turned-carer who had tried to wrest control of her father’s affairs in 2021. At that time Phillip was 88 years old and no longer capable of making his own decisions.

When she heard that the assault charge and a related application for a Domestic Violence Order against her were gone, Curro finally began to process the events that had unfolded around her ailing father in her former hometown of Ingham in north Queensland.

“I started to shake. I almost couldn’t believe that at last it was over. I just wanted to fall into the arms of my sister, my husband, my children,” she recalls. “The sense of relief, and release, were overwhelming”.

She sat down in her Melbourne home and wrote a visceral account of the attempt by extended family to “steal” her dying father.

Between April 2021 and October 2022, my sister and I faced the most vile, fantastical accusations in the [Queensland] Civil and Administrative Tribunal that we were abusing our father financially, emotionally and physically. We stole his $29,000. We kidnapped him. We caused his hospitalisation with pneumonia. We forced him to beg for money. We trampled his human rights. We made him depressed and suicidal.

We were killing our father. “The [daughters’] persecution of their father is abusive and dangerous,” they bellowed, over and over and over.

As each of 14 separate applications to QCAT to remove us as our Dad’s attorneys was rejected, our antagonists became more emboldened, their allegations more deranged. Each time the Tribunal found against them, they redoubled their efforts to cancel us from our father’s life. They ignored the Tribunal’s Order that Dad had impaired capacity for all matters. They rewrote his Will. They created a new Powers of Attorney document appointing themselves. They presented this piece of fakery to Dad’s My Aged Care provider, stopped his personal and social support services and allocated his Commonwealth funding to mowing the lawn and cleaning the house of his carer. The result was that Dad’s bank promptly removed our oversight of our father’s accounts and Centrelink cancelled my sister as Dad’s nominee.

Her raw words flowed freely as Curro sought to understand the campaign of destruction that had culminated in the assault charge. She has kept her story to herself until now, agreeing to an interview with The Weekend Australian Magazine to honour the memory of her father, and to shine a light on the growing scourge of elder abuse – the exploitation, neglect or outright abuse of older Australians, often at the hands of family or so-called friends.

Curro, now 59, still struggles to talk about the final months of the life of her dad, Phillip Curro, who passed away in Ingham on November 2 last year, aged 89. Tears flow freely as she says: “Nothing changes unless people step forward to share their stories, unless we dial up the volume and create a chorus of voices so loud that this issue can no longer be ignored. I think as a society we owe that to every elderly person.”

Elder abuse, a catch-all term that covers a multitude of cruel behaviours, is described by Attorney-General Mark Dreyfus as “a serious and growing issue in our community”. It can take many forms including physical abuse, psychological abuse, mistreatment and neglect, financial abuse and sexual abuse.

The extent of the problem is only now being realised, with the country’s first national prevalence study in 2021 finding that an astonishing one in six Australians over 65 years of age living in the community had experienced elder abuse in the preceding 12 months.

This figure is almost certainly under-reported because many victims are either too frail or otherwise unable to seek help, or are too ashamed to report their family members or friends to authorities.

The study found elder abuse is most often committed by family members, with adult children being the most common perpetrators, followed by an intimate partner, then partners of adult children. Psychological abuse (11.7 per cent) is by far the most common form of abuse, followed by neglect (2.9 per cent), financial (2.1 per cent) and physical (1.8 per cent).

It’s a subject that is only now starting to receive the attention it deserves, with the first national plan to respond to elder abuse being released in 2019, with an updated national plan by the Albanese Government now in the works.

“It’s something we have to all take responsibility for and do something about,” says Professor Briony Dow, director of the National Ageing Research Institute. “It is often hard to identify because older people themselves don’t always recognise abuse as abuse. There is also a lot of shame and stigma associated with abuse, especially if a family member is perpetrating it.”

Adds Dr Rae Kaspiew, research director at the Australian Institute of Family Studies: “What’s very concerning is that most people – six in ten – did not seek help or advice from someone else in relation to elder abuse.

“Compared to the amount of attention we have had on family and domestic violence, elder abuse is very much under-appreciated in the sense that people don’t know much about it and there is not enough discussion about what needs to be done. We need a more systematic approach to identifying and screening risk.”

One of the problems, according to Bev Lange, executive officer of Elder Abuse Action Australia, is that many people seem to think that the rights of an older person diminish as they age rather than remaining the same as any other community member. “So we need to raise awareness of ageism and what the rights are of an older person. Many victims of elder abuse are embarrassed because they’ve been abused financially or physically by people close to them, by their children or their intimate partners, so they don’t want their abusers charged, they just want the abuse to stop.”

All experts agree that elder abuse is likely to get worse before it gets better, with the number of Australians over 65 expected to double from 3.8 million to 8.8 million in the next 25 years. What’s more, longer life expectancies mean that dementia and Alzheimers are becoming more prevalent, which makes older people more vulnerable to manipulation and abuse by those close to them.

Another issue is that the relentless march of property prices means the family home is the most obvious form of inheritance, making it a tempting target for family members who might seek nefarious ways to control their parent’s finances before they pass away.

Geoff (not his real name) is a 92-year-old who several years ago agreed to move into the home of one of his two sons in a coastal town in NSW. The son, John, said he would build a granny flat out the back for his father and in return Geoff paid off John’s $280,000 mortgage and also paid $480,000 to build the granny flat.

But shortly after the granny flat was built, John announced they would all be moving to Brisbane, so the improved value of the house and granny flat that they were selling all went to John because he owned the title. Not long after they moved to Brisbane relations became frayed and John placed his father into a cheap, government-run nursing home. When Geoff asked his son for his money in order to pay for a nicer private nursing home, his son refused, saying there was no money left.

“It was absolutely devastating,” Geoff tells me by phone from Brisbane. “I didn’t feel like eating, I just felt completely numb. Fortunately, my older son came to the rescue and he got me out of the nursing home.”

The older son, Greg, says he rang up the elder abuse hotline and realised that his father had been subjected to “a textbook case of elder abuse”. At the time of writing they were planning to take the case to court.

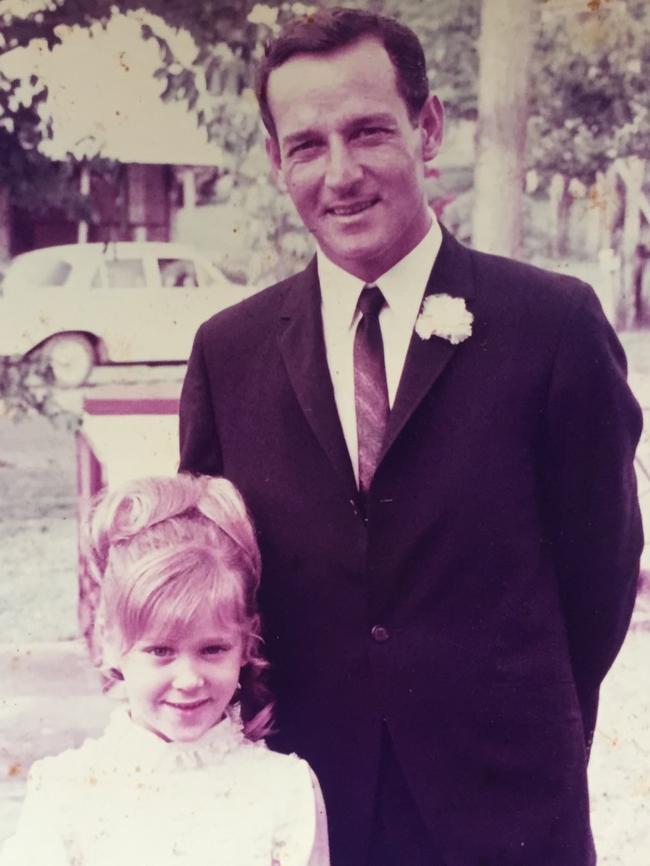

Tracey Curro’s eyes light up when asked what her dad was like. “I’ve often said he was the first man I fell in love with,” she says with a grin. “He was handsome, dashing, funny and impulsive. He commanded a room when telling stories, he loved boats and fishing, had lifelong friends and adored his two daughters and his grandchildren.”

Phillip Curro, who was a smoker from the age of 12, worked in manufacturing for a while and then ran a casino, worked as a bookmaker and ended up managing a retail store in Ingham. Curro recalls an idyllic childhood of weekends on his small boat, having BBQs on nearby tropical islands, fishing and snorkelling.

She says her dad was “enormously proud” when she went on to have a high-profile television career. Curro became a household name – and Ingham’s most famous daughter – in the 1990s when she was a reporter on 60 Minutes during the show’s heyday alongside others like Richard Carleton, Jeff McMullen and Charles Wooley. Her best known interview was in 1996, when Curro asked political newcomer Pauline Hanson if she was xenophobic, to which a perplexed Hanson, who had not heard of the word, famously replied: “Please explain?”

Although Curro eventually settled in Melbourne, she talked on the phone to her dad almost every day and in 2001 it was no surprise that he appointed his two daughters, Tracey and Peta, with an Enduring Power of Attorney over his financial and health matters. But in smalltown Ingham there had long been friction among the extended Curro clan, who were first-generation descendants of Sicilian immigrants and well known among the Italian community in northern Queensland. Curro’s parents had separated in 1994 and her mum, Laurel, died of ovarian cancer in 1996. Her father’s extended family had not been well disposed towards Laurel and therefore had little time for her daughters, Tracey and Peta.

“It was an inexplicable family vendetta, as some grudge carried across generations was prosecuted and which had its genesis before my sister and I were even born,” says Curro.

In 2019 a former partner began to take a renewed interest in Phillip Curro’s life, eventually taking on the role as his carer. By 2020, shortly after the pandemic hit, the daughters began to notice financial irregularities in their father’s finances. By this stage Phillip was legally blind and suffering from lung cancer, emphysema and vascular dementia. He was struggling to make clear decisions and had a habit of agreeing with the suggestions of whoever was caring for him at that time.

Then in late April 2020 the daughters noticed that $10,000 had been transferred from their father’s account to the carer’s account without a clear explanation. They queried the transaction, fearing that their dad was vulnerable to having his finances exploited. “This amounted to 25 per cent of Dad’s total assets, and when we queried it we were first told it was none of our business, then that it was repaying a loan, and finally that this $10k had been deposited in Dad’s name to avoid tax,” says Curro.

Tensions simmered over the transaction and in April 2021, without warning, the carer, backed by several members of Curro’s hostile extended family, applied to QCAT to remove the siblings’ Power of Attorney.

The application accused Tracey and Peta of “psychologically harming” their father by not providing him with “cash or money to contribute to his living expenses”, and claimed they were “obsessively opposed” to their father’s carer. “It’s a sad and sorry state of affairs for an old man who has done his best to ensure his children have a good life,” the application stated. The claims were not made under oath and there was no way for the daughters to immediately challenge them.

Tracey and Peta were stunned. They had ensured that all their father’s bills were paid promptly even if they were increasingly distrustful of the carer’s honesty and motives.

“We were completely blindsided,” says Curro. “First it was shock, then disbelief and then anger. We kept asking ourselves, ‘What do we do, what is the process here?’”

From that point the situation escalated quickly. Within weeks the protagonists wrote up a document appointing themselves as Phillip Curro’s Power of Attorney, ignoring the existing and valid Power of Attorney long held by his daughters. Tracey and Peta applied to be legally represented at QCAT but their application was denied and the case adjourned until December 2021, leaving the daughters with no avenue to respond to the allegations against them or to make their case on behalf of their father. In August 2021, the daughters’ access to their father’s bank account was suddenly removed by the bank, but when they queried it the bank refused to disclose the reasons for the decision. The protagonists’ invalid Power of Attorney was clearly being wielded against their father and themselves.

The protagonists set up weekly transfers of money from their father’s account to the carer. Tracey and Peta noticed that the transactions on their father’s debit card were increasingly unrelated to his needs and included spending on internet access, video games, teenage clothing and spending on cigarette brands that their father did not smoke.

“Dad had always liked to have cash in his pocket, so we would give him $1000 and then a few days later he’s got no money left and no recollection of where the money had gone. It wasn’t big stuff but it was skimming,” says Curro. Then they discovered that Peta had been removed as their father’s Centrelink nominee. The protagonists even wrote up a false will for Phillip Curro. The father who had entrusted his affairs to his daughters was gradually being stolen from them.

“All of a sudden you become like a sort of detective,” says Curro. “Screenshotting text messages, putting everything in writing and creating an evidentiary trail. You start to live in a hyper-vigilant state, and it’s exhausting and all-consuming. You think, ‘Where is the next blow going to come from? How do we defend ourselves and defend our father?’”

“We proactively gathered evidence to disprove what we anticipated would be their next allegations,” Peta says. “I started recording every telephone conversation. I wouldn’t ring Dad unless I had another phone ready to record. I knew that Dad would never remember to hang up, so I used to stay on the line and see what I could hear.

After QCAT validated the original Power of Attorney, and we decided to change banks, I rang Dad to remind him I was picking him up. When he didn’t hang up, I heard his carer ask him, ‘Where are they taking you?’ Dad said that I was taking him to open a bank account. And then I heard, ‘For what? There’s no bank in Ingham. They’re taking you to Townsville. They took control of your money and now you’re letting them take over again. Ring her back and stand up to them. Say you’re not going’. And then I hear Dad asking Siri to call me. Poor Dad. I was always thinking, ‘Poor Dad’. Another time, when his call went through to my voicemail, it recorded him saying to his carer, ‘What have I got to say?’ And the carer directs him to tell me how much rent I am to pay her.”

Despite being caught in the middle of a bitter family dispute, Curro says her father had only a passing awareness of the rift, given his increasingly frail mental faculties. “Peta and I made a decision very early on to try to shield Dad from the nature of the conflict,” she says. “So I tried to normalise conversations with him by talking about the grandchildren or a good book I was reading, just to try to make our talks a happy place for him.”

But Peta says living in Ingham as this volatile dispute was unfolding was difficult. “The hardest thing about living in a small town is that you think everybody knows, and half of them did but they didn’t know the truth.

“Even now I constantly feel like I’m being judged. I’ll see somebody and my heart starts racing. It’s awful, because you don’t know where to look and so you avoid them, or take a deep breath, stand up straight, put your head up and walk past,” she says.

When the case was finally heard by QCAT in December 2021, the sisters had become so jaded by the legal process that they held only a sliver of hope that they would regain control of their father’s welfare.

But to their delight, the tribunal delivered a decisive vindication of Tracey and Peta’s arguments. The tribunal found that the original 2001 order granting them the Power of Attorney over their father’s affairs was valid. It found that they had financially supported their father in full. And it concluded that their father lacked the mental capacity to make his own decisions on personal, health and financial matters, thereby striking out the validity of the extended family’s purported 2021 Power of Attorney document.

“I was dancing on clouds when I heard the verdict,” says Curro. “I went and bought two bottles of champagne and we celebrated. But it was short-lived. Within days they had brought another application against us. It was like playing Whack-a-Mole – you bang one set of allegations on the head and then an identical one immediately pops up,” she says.

Despite the Curro daughters winning the case, the extended family made nine more applications to try to replace and remove them as their father’s guardian between December 2021 and August 2022.

In June last year, the tense communication between the daughters and their father’s carer was abruptly severed and they all but lost contact with their father. “She didn’t allow us onto the property and she took control of Dad’s phone, so the shutters came down and we were totally isolated from him,” says Curro.

In August last year they learned, in yet another application lodged with QCAT, that their father’s health was fast declining and they feared he was being neglected. Curro immediately flew back to Ingham and went over to her father’s home to take him to the doctor herself.

When she arrived at the house, another member of her extended family was there and obstructed Tracey from taking her father.

“I had to take action,” says Curro. “I was despairing because there was an urgent need to get Dad medical care – he’d been stopped from seeing his GP for almost three months – and my relative was intent on preventing me from doing so. That was just 10 days after another QCAT judgement warning them against discouraging or hindering Dad from seeing his doctor.”

It was alleged that during the argument Curro pushed her against a wall, threw a handbag at her and then emptied a glass of water at her. Six weeks later, Curro learned she was being charged with assault, and within 48 hours that fact was leaked to the local media. Curro won’t say it openly, but it is clear she suspects it was leaked by her family protagonists, knowing they could use her public profile against her.

“I went there to help Dad shower and to take him to his doctor. My relative blocked my access to Dad and stopped me from looking after him,” Curro says, choosing her words carefully. “She refused to stop, refused to leave the premises or get out of the way, and goaded me into what was an utterly unnecessary confrontation. She had no legal or moral authority to stop me from getting Dad the care he desperately needed. I told her exactly what I thought of her in highly unambiguous terms. What did she expect? A warm embrace? My father was dying. I was at my wits’ end. Had my relative’s alleged version of the confrontation held water, would the charge have been dropped?”

Curro would later write:

For three months during the final five of his life, Dad was denied consistent medical care, supervision and pain management. His mobile phone was strictly controlled. Our access to our father was blocked. Dad suffered. He was left unbathed and unfed. Money was whittled out of his bank account. His smokes were stolen. He became collateral damage in some inexplicable family vendetta. The Tribunal’s repeated Orders that we had full legal authority to make decisions on Dad’s personal, health and medical care, his financial and legal affairs, were repeatedly breached and ignored. A Domestic Violence application was filed against me in another failed bid to undermine my relationship and deny me contact with my father. And when I attempted to take Dad to his doctor, it was I who was charged with a crime. In my hometown, a local paparazzo got the biggest tip-off of his career: “Ex-60 Minutes Reporter Charged with Assault” headlined around the country, from Cooktown to Perth.

Curro moved on from her television and radio career years ago, and has worked since as a corporate headhunter and a corporate affairs manager. She was happily married with two children, living a quiet life in Melbourne when she suddenly found herself back in the public spotlight for all the wrong reasons. “I guess when you have had a public profile, you are vulnerable,” she says. But she admits it was a devastating experience to have a vexatious assault charge in a family dispute making national headlines. “I was in a tailspin at that point,” she says.

At 9am on November 2 last year, Phillip Curro breathed his last breath at the Ingham hospital. Less than an hour after his death, at 9.52am, the executor of the invalid will phoned Curro’s solicitor. That invalid will called for her father’s body to be cremated and for a portion of his ashes to be sprinkled on the fourth hole of the local golf course.

“It was incredible,” says Curro. “For all the years I knew my father he only ever wanted to be buried, not cremated, and placed in a vault alongside our mum at the Ingham cemetery.”

Even in death, the extended family were trying to wrest control of her father.

Still, Curro held out an olive branch by inviting all extended family members – including those who had fought against her – to the memorial service. She even invited the carer to do a reading. But none of them turned up. “Those who had so righteously professed to be acting in his interests, with such vigour and for so long, chose not to attend his memorial service,” she says.

“When I found out that they weren’t coming I cried long and hard for Dad. But you know what? The consequences of that decision sit with them.”

It seems Curro has – for the most part – left behind the trauma of her father’s treatment in late life. But there is one memory that she still can’t shake, a chilling example of the deliberate neglect that so many older people suffer when they are exposed to elder abuse.

Less than a month before her father died, Curro heard that his carer had gone on a four-day holiday, and that a substitute carer was looking after him. “When we found out, my sister and I knocked on the front door, and pressed record on our iPhones,” she says. “We introduced ourselves to the carer, exchanged phone numbers, took Dad for a drive. We suggested to this kind person that we bring him his favourite meal to eat, a minestrone soup.

“The new carer was surprised. ‘So what were you told about looking after Dad for the next four days and nights?’, we enquired. She replied: ‘Just give him porridge’.”