Country singer-songwriter Michael Waugh’s touching tribute to his parents

Two deeply personal songs mean the world to Melbourne country singer-songwriter Michael Waugh. Here’s the story behind them.

When Michael Waugh was growing up in southern Victoria in the 1970s, his parents had a handful of favourite cassettes that would invariably get an airing on long country drives. Among the go-tos were the greatest hits of Dolly Parton and Kenny Rogers, two great American songwriters who shared a facility with words and melodies. None of that was much evident to young Michael and his siblings – it was a case of learning to love country music or jump from a moving vehicle.

When Dolly Parton came to Melbourne in 2011, Michael took his parents to see the Tennessee queen perform at Rod Laver Arena. By that point, the three of them had been through a lot together: his mother Eileen was in a wheelchair, having lived through a litany of illnesses including cancer while his dad John stuck stoically by her side as her full-time carer. Eileen was 15 when they met, and that was it: after a first date at the Sale drive-in, the pair were married in 1969 and they’d stayed together all the way through.

There they were, three country music fans from country Victoria, surrounded by about 14,000 people including just about every drag queen from the greater Melbourne region. During Dolly’s show, as she sat on the porch of a log cabin that mimicked the tiny house where she grew up while introducing her song My Tennessee Mountain Home, John leant over to his wife and said, “Ah, yeah, but they don’t write songs about girls from Heyfield, do they?”

It was the sort of family reference that would have gone over the heads of anyone else who happened to hear it, but Michael was struck by the economy and evocativeness of his dad’s offhand quip. While growing up, his parents had lived near one another in the neighbouring Gippsland towns of Heyfield and Maffra, rival communities a couple of hours east of Melbourne, and his mother was forever the butt of jokes about the reputation of girls from her town. What’s the definition of confusion? Father’s Day in Heyfield. That sort of thing. Crude as it sounds in black and white, that was John’s blokey way of showing his affection.

It’s true, they don’t write songs about girls from Heyfield. That’s what flashed across Michael’s mind as he sat inside Rod Laver Arena beside the two people who brought him into the world and introduced him to country music. And when he thought more about it, there was no bloody good reason why they didn’t.

So a little later, deep in the middle of marking exams while working as an English teacher in Melbourne’s inner east, Michael kept thinking about his dad’s quip. He’d pick up his guitar and write a few lines in short bursts until he made it to the final verse. That’s when the hairs on the back of his neck bristled and his eyes filled with tears. That’s how he came up with a song whose seed and soul was given to him by his father as he spoke with affection about his mother at a Dolly Parton gig. That’s how he wrote a song that begins with a pretty finger-picked guitar phrase that answered the question contained in his dad’s wisecrack.

The first time he played Heyfield Girl to his parents in their kitchen, not long after he’d finished writing it, was one of the most vulnerable moments in his life. When his father ran from the room in tears, he thought he’d upset him; when he returned, he told his son that it was a beautiful tribute to his mother.

That was only the second time that Michael had ever seen his father cry, and that memory is part of the reason it is almost always the last song he plays at any concert. Because by the time he gets to that final verse, he’s moved so deeply by the story of love and devotion wrapped in those few minutes that he can barely get the words out.

Dad used to tease mum about girls

from Heyfield

‘Cause that’s how she knows that he cares

He’d say, “They don’t write pretty love songs for girls born in Heyfield

But you’re the most beautiful woman that

I’ve ever known

Tennessee girls they might waltz

Californian girls might have no faults

Ah, but you blokes can keep ‘em ‘cause I’ve got my Heyfield girl”

Michael Waugh’s story so far is unlike anything that resembles a classic music success yarn. Some wouldn’t consider what he’s done much of a success at all: he has no shiny ARIA statues, no No.1 singles and no platinum sales accreditations. On the modern metric of streaming services such as Spotify, where an artist’s popularity or otherwise is there for all to see in raw numbers, his songs attract thousands of plays rather than millions.

By day, he’s a 49-year-old schoolteacher and married father of one son who tends not to draw much attention to himself or his sideline career in songwriting. But in the small community of Australian country and folk musicians he has established a fine reputation for himself in a relatively short period of time.

In five years, he has released three albums – What We Might Be (2015), The Asphalt and the Oval (2018) and The Weir (2019) – of such unerringly high quality that comparisons to bush balladeer John Williamson seem not just apt but natural. Like Williamson, he writes open-hearted, clear-eyed observations of Australian life, place and character while maintaining an authentic connection to where he came from. Among those in the know, he’s one to watch.

Heyfield Girl is the opening track on his debut album, while right in its centre is a song that proudly celebrates how he was raised: as the son of a dairy farmer who taught him how to work for what you love. But it’s another song from that album, What We Might Be, that truly captures the passage of time and how his relationship with his father has evolved.

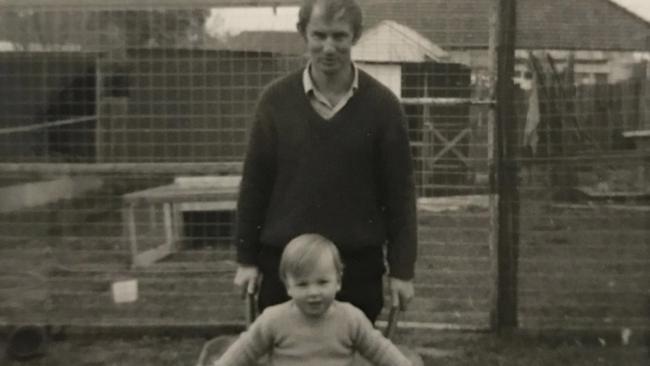

In the opening verse of My Dad’s Shoes, Michael sings about a photograph of himself “laughing when I was two or three / standing in dad’s Blundstone boots that are twice as big as me”. Those shoes become a metaphor for the strength and resilience he saw in his old man, and how Michael now wants to be seen by his own son: as someone who works hard for his family, and who digs his heels in for what’s true. Following the classic country songwriting form, it’s in the third verse – just before the lead instrumental break – that the singer truly sharpens his knife and cuts to the heart of the matter:

When I was a young man

I got too big for my boots

And I tried lots of styles but the soles have all worn through

Now that I am older and the sneakers just don’t suit

I’m proud to wear these Blundstone boots like you

As a young man, Michael used to dream that he’d one day make glamorous music videos packed to the gills with supermodels, like those he saw from British pop group Duran Duran. Instead, he ended up making music videos starring his mum and dad.

Once he’d finished recording his debut album with producer and multi-instrumentalist Shane Nicholson – who has worked on all three of his albums to date – Michael and a filmmaker friend named Ryan Tews drove to his mum’s hometown with the idea of stopping and asking random women if they’d like to appear on camera for a few moments, in order to illustrate the world’s first song written for girls from Heyfield, the timber mill town in east Gippsland.

Their strike rate wasn’t great: plenty of women were rightly leery of two out-of-town blokes rocking up with a camera, asking strange questions. Plenty more thought they weren’t pretty enough for that sort of thing. But a few agreed, and their character-filled faces grace the four-minute film: fish and chip shop owners and bartenders, and mums, sisters and grey-haired grandmothers from the country.

Later, the two blokes returned with Michael’s parents. While driving around Heyfield together, the foursome stopped in front of the house where Eileen was born in 1950. That beautiful shot of her standing and smiling outside a red-brick home on a sunny day appears towards the end of the video, and it’s immediately followed by a tight shot of John and Eileen standing next to each other, laughing. What was so funny? Well, when the director had the camera on them, he asked John if he could do something to make his wife laugh – so he farted. That shot and their reaction is immortalised on YouTube, so whenever Michael or his siblings or anyone else who knew the pair watches the video, they’ll see a moment in time where, right on cue, John cut the cheese beside his Heyfield Girl.

There’s no disguising that it has been a shithouse few months for the Waugh family. When John died in January, aged 76, it felt likethe world was on fire as large tracts of the nation’s eastern states burned. And when Eileen died in March, aged 69, the world was entering a pandemic that would cause major death and disruption. The two people who had brought Michael into this world left him here six and a half weeks apart; both spent their final days at a residential aged care facility in Sale.

His dad had died of a rare lung disease a week before Michael was due to be in Tamworth for the annual country music festival. Michael’s first instinct was to cancel everything to be with his family, but they all told him he was kidding himself if he didn’t think his old man would have wanted him to play those shows. So he kept his plans and went to Tamworth while dragging a wrecking ball of grief in his wake; 13 shows all up, he played, always telling the truth about what he was feeling because that’s what he was raised to do, and it wouldn’t have made any sense to hide it. He didn’t always get to the end of a performance without crying, but he gave it a crack anyway.

At every show that week, it felt like he was walking into a hug. Friends and fans in the audience knew what he was going through and shared kind words with him after he packed the guitar away. Time and again listeners thanked him for the chance to get to know his dad through his songs, and even in the middle of it all, the part-time musician recognised the value and power of what he’d decided to do all those years ago when he tried to capture a sketch of his father in a few verses wrapped around a few chords.

All the way to the end, John didn’t want to talk about his illness, or death or dying. When he was gone, Eileen was annoyed because he hadn’t indicated how he wanted to mark his passing. Burial or cremation? No idea. A church funeral service, or a memorial held somewhere a bit less traditional? Not sure. The only thing he said to anyone was that he wanted his son to sing My Dad’s Shoes. Talk about a tough gig: is there a greater test in a man’s life than being asked to sing a song about his father at his father’s funeral? In the run-up to the big day, Michael ran through it five times at home, crying his guts out. At the service, one of his musical mates stood by his side to offer back-up vocals and emotional support, and to pick up the singing in case Michael lost it. He sang it loud and proud and afterwards he placed a pair of his dad’s Blundstone boots atop the coffin as it was lowered into the ground.

John died at 5 o’clock in the morning, and halfway through that smoky three-hour drive from Melbourne to Sale – with his wife in the passenger seat in the role of human jukebox, taking requests to play songs that reminded him of his childhood country drives with his parents – Michael felt the urgent need to pull over and start a group chat with all the people he’d made music with.

First, he had to tell them his dad had died. Second, he had to tell them how much it meant to him that they had helped him to create songs about his parents. While they lived, the songs were proof of a son’s love for his mum and dad. They were evidence of emotions deeply felt and shared. He thanked his little musical crew for enabling him to pass that message on so that there was no doubt in their minds.

Weeks later, another funeral, and just as he sang for his dad, he would sing for his mum. Heyfield Girl, of course.

They don’t write pretty love songs for girls born in Heyfield

But you’re the most beautiful woman that I’ve ever known…

As this whole story of love and loss unspools during a long and emotional phone call a week after Eileen’s funeral, Michael is reminded of a hit pop song from 1988 by Mike + The Mechanics, because that’s how his mind words: music is wrapped in the very fabric of life.

Anyway, you know that song The Living Years? There’s a bit in the middle eight where Mike Rutherford sings about what he wishes he’d been able to say to his father before he died. What pleases Michael more than just about anything else on earth is that the bittersweet sentiment of that pop hit just isn’t true for him. Through song, he got to tell his dad and his mum exactly how he felt. They didn’t have to wonder. They knew.

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout