Class action: when a legal victory leaves a toxic aftertaste

When $87m of a class action payout is soaked up by fees and commissions, with a ‘pittance’ left, who’s the real winner?

The people who live around Williamtown, half an hour’s drive from the coal-port city of Newcastle in NSW, have a proud history of blue-collar bolshevism. When coal seam gas drillers tried to start operations in this community eight years ago, residents won a court injunction and staged a blockade in which local mothers chained themselves to a tractor. So when news began spreading that toxic chemicals from the local RAAF base had contaminated the ground and water under their homes, a fight was more or less predestined.

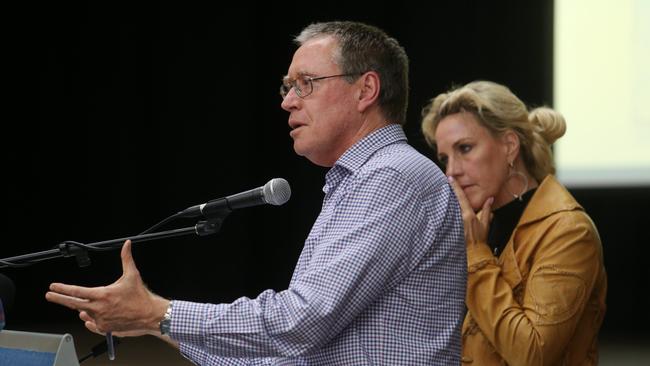

That was in September 2015, a time when the Department of Defence was still assuring people there was nothing to be alarmed about. Rob Roseworne was one of the first locals to discover a different side to the story. The chemicals seeping into local aquifers came from firefighting foam that had been sprayed for decades on the base during practice drills, and medical studies had shown they had caused testicular and liver tumours in animals. Roseworne, who lives with his wife on a 2ha property where he also runs a dog kennel and cattery, helped spearhead a push to sue the Federal Government for compensation.

“The commander of the RAAF base had promised, ‘We’ll look after you’,” recalls the 55-year-old, whose home backs onto a creek 2km downstream from the RAAF base. “But when our questions started being directed to government lawyers sent up from Canberra, it became obvious the Defence Department was going to play hardball. The logic was: if they had lawyers, we needed lawyers.”

More than 500 residents eventually signed up to a class action lawsuit filed on their behalf by the Sydney law firm Dentons (then known as Gadens) in November 2016. By then it was clear that pollution from firefighting foam was a massive nationwide problem: the toxic foams had been used at hundreds of defence bases and firefighting stations around Australia, and blood tests of residents living near these facilities were turning up disturbing results. A five-year-old girl living near the Oakey army aviation base near Toowoomba, Queensland, recorded blood levels of two chemicals – perfluorooctane sulfonate and perfluorooctanoic acid – at 30 times the national average. These toxins, which are prevalent in the environment thanks to their use in Teflon, packaging and waterproofing, are so difficult to eradicate that scientists have struggled to estimate their half-life.

A second class action lawsuit was soon launched by the Oakey community, followed by a third on behalf of people living near RAAF Base Tindal in Katherine, NT. All three were backed by IMF Bentham, an investment outfit with an unusual business model: the company, which recently changed its name to Omni Bridgeway, invests in lawsuits by paying the upfront legal fees in exchange for a cut of the settlement money. It’s a form of “litigation funding” that Australia pioneered and has exported to the world.

In late February, after more than three years of court hearings and failed mediation talks, Defence agreed to settle all three lawsuits for $212.5 million. Lawyers for the communities hailed the result as “total vindication”; in Williamtown, residents posed for the media punching the air in victory. It was only over ensuing weeks that some harder truths emerged. The people of Oakey, whose lawyers had once predicted would win a $200 million payoff, would get only $16.4 million shared among about 450 people – $36,000 each on average. The Williamtown payout totalled $54 million shared between a similar number of people, but to Rob Roseworne and others it was hard to see how that would get them out of the trap they were in.

Then came another revelation: lawyers for the three communities had reaped $30 million in fees from the case, and the litigation funder estimated its profit would be $51.5 million. More than 40 per cent of the settlement would be swallowed up in fees and commissions, while people such as Roseworne faced the prospect of either selling their devalued homes and businesses at a big loss or staying put on contaminated land. “We’re looking at a pittance,” he says bitterly. “But the funder has made a fortune.”

Last year was the busiest on record for class action lawsuits in Australia. To take a few examples, National Australia Bank’s customers sued over excessive fees on their super accounts, and four companies – biotechnology firm Sirtex, engineering concern UGL and dairy companies Murray Goulburn and Bellamy’s – forked out a collective $150 million to settle shareholder lawsuits over their business practices. In November, 6800 Queenslanders won a negligence case against state water authorities relating to the devastating 2011 floods, a victory that could cost the state government hundreds of millions of dollars.

Each one of those lawsuits was funded by IMF Bentham, a company named in part after Jeremy Bentham, the 18th-century British legal reformer whose credo of “levelling the legal playing field between the poor and wealthy” is cited on its website. According to Vince Morabito, a law professor at Monash University, litigation funding is a business innovation that Australians exported to the world: banned for centuries under British law, the practice was kickstarted in 1996 when the Federal Court allowed insolvency practitioners to seek outside funding for lawsuits. Morabito says IMF Bentham was the first funder in the world to bankroll a class action lawsuit – a 2002 case in which several shipping companies were sued by former contract employees. (It was an early win, with an $8 million settlement.)

Since then the practice has become increasingly common in Australia thanks to a series of legal reforms that have loosened the constraints on class actions and led to a jump in their numbers (62 new class actions in 2018-19 compared to an average of 32 annually over the previous five years). Lawyers who work in the field hail this as a win for ordinary people, because the cost of suing large corporations and government departments can be prohibitive without a funder to pay the lawyers – not to mention paying the other side’s lawyers if the case fails. The Queensland floods case lasted nearly five years, including an 18-month trial that cost IMF Bentham and a co-funder around $50 million in legal fees.

‘The court system should not be undermined by proceedings that disproportionately benefit the funder and/or solicitor rather than the litigants’

Most class actions don’t actually resemble that case – more than half involve shareholders or investors suing companies over governance issues, a burgeoning business that is causing angst in corporate boardrooms and has prompted the launch of a parliamentary inquiry. Judges have increasingly begun to voice their ire about the costs associated with such lawsuits. In 2016, NAB customers won a settlement of $6.6 million over excessive fees but, in an ironic coda, IMF Bentham took $4.1 million of it in funder’s commission. That 62 per cent cut was nearly outstripped by a 2018 case in which several hundred Bank of Queensland customers sued over the fraudulent misappropriation of their retirement savings; they won a $12 million settlement, but their lawyers and their funder, Vannin Capital, presented them with a bill for $11.75 million. Justice Bernard Murphy rejected the fees as “plainly disproportionate” and insisted that one-third of the settlement money be set aside for the actual claimants – noting that even this improved share might disappoint some of them. The court system, Justice Murphy tartly noted, “should not be undermined by proceedings that disproportionately benefit the funder and/or solicitor rather than the litigants”.

Federal Attorney-General Christian Porter has already flagged that such issues will be targeted in the pending parliamentary inquiry into class actions, along with the scant regulation of funders, which are currently not subject to licensing requirements or supervision by the prudential authorities. The Williamtown and Oakey lawsuits might well get an airing in those hearings.

The story of how the US chemical company 3M invented a benign-sounding firefighting foam called Light Water that has spread its toxins through rivers, farmlands and homes around the world is worthy of a Hollywood drama – which it now is (Dark Waters, starring Mark Ruffalo).

3M began adding the chemicals known as per- and poly-fluorinated alkyl substances (PFAS) to firefighting foam used by the US Navy in the 1960s, and their extraordinary ability to snuff out liquid fuel fires made them ubiquitous in both civil and military use. In Australia, hundreds of fire stations, airports, mines and military bases used 3M Light Water and other PFAS foams, unaware for decades of their potential toxicity to humans.

Around Williamtown, locals still remember seeing children playing with the foam when fire fighters visited schools in the area. “It was a great product,” says Lindsay Clout, who first encountered 3M Light Water more than three decades ago as an electrical contractor in NSW mines, then came across it again after moving with his wife to a 30ha farm near the Williamtown RAAF base in the early 1990s. “Every other day they were out there on the base training with it, spraying it everywhere. And of course, this is a floodplain – it just ended up in the drains.”

Like many locals, Clout was drawn to the region by its semi-rural coastal setting – generous acreage blocks with the ocean on one side, the Hunter River to the south and the city of Newcastle nearby. Clout raised cattle here until he gave it up 15 years ago to start a garden supply business on his property. Unbeknown to him and everyone else in Williamtown, the Defence Department already knew – thanks to a 2003 report from its own environment officers – that overseas research had warned that the chemicals in Light Water could have toxic health effects, and that shoddy waste management on Defence bases meant the chemicals may have contaminated “neighbouring properties, creeks, dams and reservoirs”. The US Environmental Protection Agency had warned Australian environment bureaucrats in 2000 that the chemicals could have severe long-term consequences to human health.

That same year, 3M had announced it was phasing out Light Water and all other PFAS products, and in 2005 DuPont – which manufactured the chemicals – paid a $16.5 million fine to the US government for concealing their potential toxicity. Despite all this, the Defence Department in Australia did not begin testing its sites for the chemicals until 2011. The results were alarming: in May 2012, it told the NSW Environmental Protection Agency that water flowing off the Williamtown RAAF base had elevated levels of PFAS.

It would take another three years for Defence to confirm that contamination had spread into surrounding groundwater, prompting the state government to close local fisheries in August 2015 – a move the department opposed. By then people living around the base in Oakey had already learnt their water was contaminated and had contacted Shine Lawyers, unimpressed by a Defence assurance that the only health effect they might face was “a rise in cholesterol”. Eradicating PFAS chemicals from soil is diabolically difficult, and a 2011 study financed by DuPont had shown that they caused kidney, testicular and other cancers in animals. In early 2016 The Courier-Mail commissioned blood tests and water sampling for the family of Brad Hudson, a horse breeder whose property was 400m from the Oakey base and who had suffered testicular cancer. The bore water Hudson’s family drank had 23 times the maximum allowable levels of PFAS and his five-year-old daughter had levels in her blood that were 30 times the Australian average.

In Williamtown, local media revealed that Defence had initially tried to keep the contamination “confidential”, and residents were furious when their request for blood tests was at first knocked back. “People’s questions weren’t being answered,” recalls Lindsay Clout. “It was quite clear to everyone that it was a snow job.”

The contamination plume grew over time, eventually affecting 25 square kilometres and more than 750 families. Even those outside the zone discovered banks were reluctant to loan them money. Rob Roseworne’s kennel business became moribund and a property valuer told him his place was now worth “zero”. Residents began speculating about mysterious illnesses that had afflicted their greyhounds, alpacas and chickens.

The community formed three action groups and approached several law firms before settling on Gadens, now known as Dentons. Roseworne recalls a meeting where the lawyers first suggested IMF Bentham come aboard as the litigation funder. “I remember thinking, ‘What’s a funder?’” he says. IMF Bentham’s “condition precedent” was that 450 residents join the action before it would tip its own money in. Community meetings were held and people went doorknocking to encourage their neighbours to sign up.

‘I didn’t want to join the class action, but I thought it was the only way we were going to get anything’

For many residents, the class action seemed their only hope of recouping enough money to sell up and get off the contaminated land. Defence had set up a compensation system but its reputation for playing hardball was well known, and the CFA in Victoria had already refused to pay compensation to firefighters who believed their cancers were caused by PFAS exposure. Jenny Robinson, a Williamtown resident who lived next door to the RAAF base and had just been diagnosed with breast cancer, says pursuing an individual claim seemed daunting. “I just didn’t think we could afford a lawyer. I didn’t want to join the class action, but I thought it was the only way we were going to get anything. I was undergoing chemotherapy, and I just didn’t want to deal with it.”

In its meetings with residents, IMF Bentham made it clear that 25-40 per cent of any settlement could be swallowed up in legal fees and commissions; it also brought along solicitors from other firms to offer independent advice. Still, several residents recall it as a high-pressure sales pitch: the case could be over quickly and IMF offered a “no-risk” path, as opposed to the huge risk of going it alone against the Commonwealth. “The message was: ‘This stuff could kill you, you need to get out of there, you need to be able to make your own choices in life’,” recalls Roseworne, who was among the first to sign up.

Up in Queensland, Shine Lawyers had paid US environmental crusader Erin Brockovich to visit Oakey, generating massive publicity. In March 2017, IMF Bentham agreed to fund that lawsuit on behalf of 450 residents, and Shine’s special counsel Peter Shannon told the media he’d be surprised if it cost Defence less than $200 million in compensation. Five months later, Shine and IMF teamed up for a third class action on behalf of 2000 residents living near RAAF Base Tindal in Katherine. All three lawsuits would be later joined into one case at the direction of a Federal Court judge.

Brad Hudson, the Oakey horse breeder whose property had been grossly contaminated, became the lead litigant in the Oakey case and suffered a backlash from community members who blamed him for damaging property values by drawing attention to the problem. In 2017 Defence approached Hudson with an offer to resettle his family outside the contamination zone on an equivalent property, an offer he rejected for reasons he declines to comment on. Around the same time, a Queensland lawyer named Adair Donaldson began negotiating privately with Defence on behalf of his father, a retired doctor who lived near the Oakey base. Donaldson had advised his father not to join Shine’s class action, and in March 2019 he successfully reached a private settlement with the Commonwealth.

Back in Williamtown, the stresses of the case also frayed relationships, even as the community presented a united front to the media. Blood tests showed elevated levels of PFAS, causing anxiety for parents of young children; environment officials told people inside the primary contamination zone not to use bore water for any purpose and to avoid eating home-grown food and meat. Many people felt trapped in unsellable homes on contaminated ground and marriages crumbled as couples argued about whether to stay or flee. Rob Roseworne fell out with the other community leaders because they were enlisting local state Labor MPs to attack the Turnbull government over an issue he believed both major parties had been negligent about.

Early on, the two law firms behind the class actions had resolved to focus the case on fallen property values, avoiding the contentious issue of whether residents’ illnesses could have been caused by the chemicals. Proving such a direct link would have involved complex medical argument, and Defence to this day asserts there is “limited to no evidence” of disease or significant illness from PFAS exposure. But even on the limited issue of property losses, Defence resisted an across-the-board acquisition offer and negotiations for a deal dragged on into 2019.

Late last year, Justice Michael Lee set the matter down for trial in April and ordered independent experts to evaluate both property losses and the medical evidence on PFAS exposure. Those reports were filed with the Federal Court on Christmas Eve, and proved to be very bad news for the Commonwealth: the property expert concluded that Brad Hudson’s equine property in Oakey had suffered a 31 per cent hit to its value; the medical expert, Associate Professor Nick Osborne of the University of Queensland, concluded there was “general agreement” in the scientific community that PFAS chemicals could potentially cause kidney cancer, testicular cancer and high cholesterol. Within weeks, the Commonwealth was negotiating to settle the case, reaching its $212.5 million deal in late February.

A major selling point of class action lawsuits is that they enable ordinary people to band together and achieve strength in numbers. But when 500 people make a claim for damages, some will inevitably have a weaker claim for compensation than others, and the lawsuit can become a source of dispute rather than unity.

The contamination in Oakey was particularly alarming for people such as Dianne Priddle and David Jefferis, who raised Charolais and Charbray cattle on an 80ha stud they bought in 2005, and had been compelled to stop using bore water. The couple say Defence told them repeatedly not to eat meat from their property, and they believe the contamination plume, which is gradually growing, has slashed the value of their business and home. Last month they received notification about the compensation they can expect from the class action, and while Priddle declines to discuss the figure, she does not sound happy. “Have I written to the judge? Absolutely,” she says. “I want to know how they’ve come up with [that figure].”

Who gets what from the $212.5 million will be determined by multiple factors such as proximity to the base, type of property and use of bore water. Many people who signed up to the lawsuits but were not severely affected may well be happy to take the settlement on offer; others are wrestling with the dilemma of whether to voice an objection and risk derailing the whole deal.

Kim Smith, whose husband Gavin was the lead litigant in the Williamtown case, argues that for many people the outcome will mean a guaranteed payment they couldn’t have won any other way. “Realistically, where would we be otherwise?” says Smith. “We worked very closely with the lawyers and I can honestly say they worked tirelessly to help us. We have made this a national issue.”

For others such as Rob Roseworne and Jenny Robinson, however, the settlement has left a bitter taste. They knew the lawyers and funders could take up to 40 per cent of the settlement, but assumed there would be enough left over to compensate their property losses. “If we don’t get enough money to move out, we’re stuck,” says Roseworne. “We’re still contaminated, we’re still exposed to the product. But the lawyers will be asking us to sign documents saying ‘no future claims’.”

One lawyer who supports these grievances is Adair Donaldson, who negotiated a payout from Defence for his father in Oakey. Donaldson says the contract Shine Lawyers offered Oakey residents was so convoluted that it was difficult to determine what the net payout might be. He described the funder’s $51.5 million profit as “obscene” and said the lawsuit highlighted a fundamental problem with class actions – “the weak cases ride on the back of the strong cases. It’s great for litigation funders and lawyers but I’m not so sure it’s the best thing for claimants.”

Andrew Saker, the boss of IMF Bentham/Omni Bridgeway, says that a $51.5 million profit may seem generous but his company signs a “blank cheque” with every case and can sustain huge losses if unsuccessful. Its recent victory in the Queensland floods case is now subject to appeal, and Saker estimates the company’s exposure could be up to $50 million if it loses.

Four years ago the company won a case against ANZ Bank on behalf of 150,000 customers charged excessive fees, only to have it overturned on appeal. “We spent $15 million and we paid out adverse costs of $13 million,” he says. “But even though we lost the case, people no longer have to pay fees for dishonoured cheques and overdrawn accounts – those things have disappeared, because we were able to modify banks’ behaviour.”

Saker asserts his company’s return on investment in these cases is always higher with an early settlement. “The reason this case cost so much is that the Commonwealth just refused to settle until shortly before trial,” he says. “Information about the damage from PFAS chemicals has existed for more than 20 years; there were two Senate inquiries. This was a case that screamed out for early settlement, but it didn’t. We had to show the Commonwealth we were prepared to take the fight all the way. As it turns out, that was actually worse for us.”

Dentons and Shine, the law firms that represented the three communities, argue the PFAS lawsuit is a shining example of how class actions can achieve justice for people who would ordinarily be frozen out of the legal system. Ben Allen, the Dentons partner who ran the case, says it will “likely come to be seen as one of this country’s greatest community-driven campaigns against the Australian Government… Some will seek to distract from that and make this all about the process, class action funding or compensation.”

Asked why the Oakey settlement was only a fraction of the projected $200 million-plus, Joshua Aylward of Shine says it was based on many factors including land valuation and toxicology reports. “The adequacy of the settlement is a matter for the Federal Court,” he adds. It will adjudicate the issue at a hearing early next month.

Shine made $20 million from the lawsuit and has now rolled out Erin Brockovich for a slick new video promoting its latest PFAS class action, filed on behalf of 40,000 people living in seven communities including Townsville, Wagga Wagga and Darwin. The lead litigant is Reannan Haswell, a young mother living with her husband and children near RAAF Base Pearce in Western Australia, who said she had been encouraged to take the action by Shine’s success in Oakey and Katherine.

Back in Williamtown, people are still waiting to learn what their final settlements will be. Lindsay Clout says philosophically that he’s looking to a future when the contamination is eradicated and people’s lives can get back to normal. He thinks the lawsuit was valuable in “applying the blowtorch” to the Federal Government, although he admits it will be a disappointing outcome for some. Rob Roseworne, meanwhile, wonders increasingly whether health conditions he and his family have suffered are linked to the chemicals that still taint the water. Would he consider legal action over that, after everything that has happened? “Absolutely.”

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout