Citizenship saga a ‘low point’ in Australian politics, Erica Frydenberg says

When Josh Frydenberg’s family history was weaponised for political purposes his mother Erica kept her counsel throughout and channelled her energy into something positive.

Every now and then Erica Frydenberg will dream about being in a confined space. It’s not a sharp memory, the type that keeps you up at night; it’s more a feeling of being restricted, a sense of claustrophobia that creeps into her consciousness.

She doesn’t know if her dreams are tapped from a well somewhere deep within, or stitched together from the memories her older sister has shared over the years. Either way it doesn’t matter. The earliest days of her life, when she was hiding from the Nazis in a basement in the Budapest ghetto, still float around her mind almost 80 years on.

Call it a twist of fate, a lucky escape, an outright miracle, call it what you will, Erica Frydenberg really shouldn’t be here.

She spent the first year of her life in a Red Cross children’s home in Budapest, the Hungarian capital, after her parents hid her there hoping she would be out of reach of the Nazis who were ripping Jews from their beds and sending them to deaths at the concentration camps. But as the Luftwaffe showered Budapest with bombs, systematically razing the city, Erica’s parents reasoned that the basement they shared with dozens of Jewish families might in fact be safer.

“In the middle of the night my uncle and my mother came to get me but the janitor told them that there were no children left, they’d all been evacuated to a safe house in the country,” Frydenberg explains. “My mother heard a baby cry, but she was told they were the children who were sickly or unwell and weren’t going to survive. Thankfully she insisted on looking, because I was one of those babies. I was underdeveloped and probably malnourished and weak, so it was deemed that I wouldn’t survive. But here I am.”

Suffice to say the Melbourne psychologist and academic, who also happens to be the mother of Australia’s former treasurer, Josh Frydenberg, had much to draw on when she wrote her latest book, Coping in Good Times and Bad, a handbook for developing resilience and fortitude.

“It just shows that you can have good fortune in life, you can overcome adversity – and that’s always been the message in my family: don’t dwell on the difficult times, get on with it and make the most of life.”

Erica Frydenberg AM isn’t one for the public eye. In fact over the past decade and particularly since her son became treasurer, the Associate Professor of Psychology at the University of Melbourne’s Graduate School of Education has largely kept out of the media spotlight, believing one Frydenberg on our televisions each day was enough.

But as she celebrates the release of her 25th book, the once passionate feminist who was taught by Germaine Greer is finding her voice.

“I’ve lived through the most wonderful years in our country – free education, quality education, opportunity for all, full employment. Australia is a wonderful place, but we need to educate, not hate,” she says, noting that two days before we meet for this interview, militant neo-Nazi groups have marched on the streets of Melbourne flaunting the Nazi salute.

“I sometimes think that people invoke these images without fully understanding that period and what really went on. The point about history is to be able to appreciate where we are now and how our lives have been enhanced by others before us, and how good people can prevent bad things happening.”

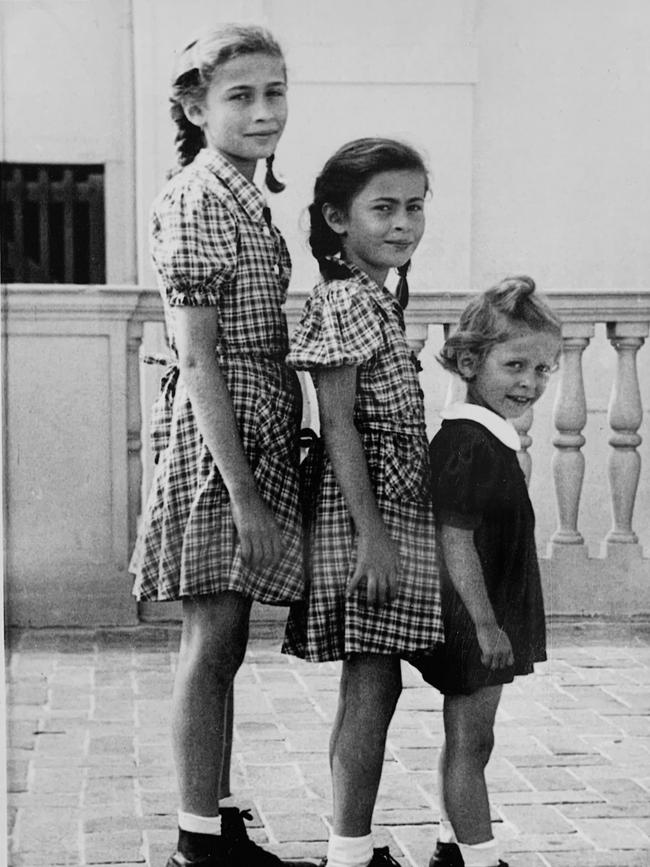

Erica Strausz was seven years old when her family sailed into Sydney Harbour on the Surriento, having survived the Holocaust and the emergence of the brutal communist regime in Hungary that followed. Grateful for the opportunity of a new life, Sam and Ethel Strausz established a belt-making business from the kitchen table of their small Bondi apartment. They were humble beginnings but they were free.

Although Sam and Ethel never spoke about the Holocaust, lest it shadow their children’s upbringing, a sense of injustice and a passion for making things better led Erica to study psychology at the University of Sydney, pursuing a lifelong interest in understanding humanity and why humans do the things they do.

To say it was a formative time in her life is an understatement.

Inspired by Germaine Greer, her second-year English tutor in 1963, she took to the streets with gusto, embracing the feminist spirit that has guided her ever since. “Germaine was visibly strong and powerful and so strident,” she recalls. “I remember her coming into class wearing long leather boots, and putting her feet up on the desk … we were only a small group and she would take us through very thought-provoking questions. She was intimidating because she was so clever, and in her presence I was meek and mild, but she taught us so much. Her ideas were something I really adopted; she really resonated.”

Female role models were the backbone of Frydenberg’s life – particularly her mother, who shouldered much of the burden of running the family’s belt-making business while caring for her husband Sam who suffered greatly from his experiences during World War II.

She says that she was surrounded by strong, capable women, and by the time the feminist models of the ’60s emerged, she was itching to be part of the movement. “My children will be quite horrified I’m sharing this,” she says as she recounts the story of how she once went for a job interview in a flimsy summer dress – quelle horreur – without a bra. “Not wearing a bra was the ultimate symbol of freedom,” she laughs. “I really should have looked in the mirror before I went, and needless to say I didn’t get the job, but I thought I was making quite a bold statement.”

While at university she met Harry Frydenberg; they married in Israel in 1967, before returning to live in London. Young and free, they travelled around Europe and regularly joined marches, particularly protesting against the Vietnam War; they took part in some notable protests, including one in London’s Trafalgar Square in March 1968, which culminated in clashes outside the US Embassy and the arrest of 200 people.

When they returned to Australia, Frydenberg threw herself into her work. She focused on the social and emotional wellbeing of children and families, a topic close to her heart.

To date, as well as authoring and co-authoring 25 books, she has had at least 47 research papers published internationally. Although semi-retired, she remains a Principal Research Fellow at the University of Melbourne and is still actively researching, contributing to podcasts and journal articles, teaching and mentoring – building a better world. She is currently writing a new book for release next year.

“If you feel strongly about something, get involved. That’s very much part of my family’s DNA”

“In the ’60s there was still an expectation that when you married you didn’t work. I never thought about not working, it never crossed my mind,” she says. “I wanted to work because that was the path to independence and life satisfaction. For me, it’s about being a contributor to society. Participation in life and community is important – if you do good, you feel good, and if you feel strongly about something you should get involved. That’s very much part of my family’s DNA.”

While her son Josh, who became federal treasurer in 2018, has been the most high-profile member of the Frydenberg family, her husband Dr Harry Frydenberg AM is regarded as an Australian pioneer of bariatric surgery and daughter Dr Lexi Frydenberg is a prominent paediatrician at Melbourne’s Royal Children’s Hospital.

“Our family is very much about doing – we always want to be involved and doing something to make a contribution, it gives purpose and meaning to our lives,” Frydenberg says, choosing her words carefully when asked how she felt about the results of last year’s federal election when her son lost the once blue-ribbon seat of Kooyong.

“Josh gave the election and the electorate his all, and like him I am philosophical about the loss,” she says. “Beyond the initial disappointment there has been an upside, as it has given him more precious time to spend with his young family.”

In 2017, to Frydenberg’s surprise and disbelief, her painful family history became the subject of a bitter public battle when questions were raised about whether her son had “inherited” Hungarian citizenship.

Section 44 of the Constitution does not allow dual citizens to sit in Parliament, and that same year 15 MPs including then Deputy Prime Minister Barnaby Joyce were referred to the High Court to test their eligibility, forcing a number of by-elections around the country.

The Frydenberg case seemed cut and dried. In October 1943, as the Nazis were steam-rolling across Europe, Ethel Strausz gave birth to her second daughter Erica in Budapest. Six months later the Nazis arrived.

Just after Erica’s first birthday in November 1944, the Royal Hungarian Government decreed the establishment of a ghetto, and Jews were dragged from their homes and herded into a squalid space. Their apartments were occupied by the Nazis. As with other ghettos established by the Nazis around Europe, the area was bordered by a patrolled wall, totally cut off from the rest of the city. No food was allowed in, rubbish and waste weren’t collected, and the dead lay on the streets. Buildings were overcrowded and disease, particularly typhus, quickly spread. In a lightning blitz to complete Hitler’s work, deportations began immediately, with many Jews sent to their deaths at Auschwitz-Birkenau or on death marches.

Budapest had been the centre of Hungarian Jewish cultural life, and was once considered a safe haven for Jews from other countries, but by the time the city was liberated in February 1945 the Jewish population of 200,000 was reduced to 70,000. An estimated 80,000 Jews had been shot on the banks of the Danube.

“My father and my uncle were marched to the banks of the Danube at gunpoint by the Arrow Cross [German allies],” Frydenberg says. “Whoever tried to shoot my uncle misfired and miraculously the bullet missed him. He and my father survived. My immediate family were somehow very fortunate but we lost many members of my extended family and we are still trying to unearth what happened to them all today because my parents didn’t speak about it, partly to protect themselves and their children from the pain, but also because there was a great sadness that they couldn’t save everyone.”

Frydenberg arrived in Australia in December 1950 as a “stateless” person. The matter should have ended there. However, after the federal election in 2019, a climate activist from her son’s Kooyong electorate took the claim to the High Court.

For years the case dragged on, with Frydenberg’s family history weaponised for political purposes, dissected by the courts and political extremists. Tellingly, many of the treasurer’s most ardent political rivals came out in support of his family, calling the campaign “grubby”, “offensive” and “abhorrent”, suggesting undertones of anti-Semitism. Even Left-wing lobby group Get Up! condemned the action, while Tanya Plibersek and her colleagues reached across the aisle describing is as “a bridge too far”.

Josh Frydenberg convincingly won the case in 2020, but the activists continued their campaign on the streets of Kooyong during the 2022 election campaign.

Erica Frydenberg kept her counsel throughout. Instead, she took to the keyboard, channelling her energy into something positive, using decades of research to write a new book that offers strategies for coping, dealing with stress and building resilience in everyday life.

While “coping” has become part of our everyday vernacular, she says that learning helpful coping strategies and reducing the use of unhelpful ones is the key to wellbeing.

She is still reluctant to dignify the citizenship challenge with too much commentary, but says it reflects a “low point” in Australian politics.

“I suppose there comes a time where nothing surprises you, sadly. It was a period of enormous hostility in the political environment, but I had the confidence that Josh would deal with it and he did,” she says. “What they were doing seemed so wrong, but they still did it.

“There is an irony in using a period of such hate in history to do something hateful. I wonder, do they really appreciate the extent of the pain and trauma that occurred in the Holocaust?”

As it turned out, the interest in her family’s history, albeit in this unwelcome way, has inspired Frydenberg and her family to piece together their story, and later this year she and her husband will travel to Hungary to retrace her footsteps, and to hopefully put the lost pieces of the jigsaw puzzle in place.

Further, Frydenberg is now working a new book of Holocaust survivor stories that will focus on unsung good deeds. She hopes the book will shine a light on the good things humans do to help others, and continue to help educate the community about the Holocaust.

“The use of those symbols of hate concerns me greatly,” she says of the recent neo-Nazi march on Melbourne’s streets. “A lot of these things are born out of discontent and malcontent and must be handled very carefully. You see over time that if these sorts of groups gain momentum the outcome is very destructive.”

“My next book is about finding the good in people – looking at the good things people did and the impact of their efforts. We need to learn from history and share it in a way that is educative and uplifting.”

For the record, she is keeping mum about whether she wants her son, long-touted as a future Prime Minister, to make another run for politics. “That’s a very interesting question!” she says, with a grin that says If only I had a dollar for every time I’ve been asked that…

“I’ve never chosen my children’s careers, they’ve both followed their own paths. I don’t know what Josh will do; he will no doubt take into account what is right for him and his family. Josh is very much his own person and I trust his judgment. Whatever decision he makes about his future, my wish is that he does good for the community in whatever role he undertakes – do good and do the best you can.”

Coping in Good Times and Bad, Developing Fortitude is published by Melbourne University Press, priced $32.99.

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout