Childhood cancer in Australia will be conquered in a generation, leading researcher Michelle Haber says

The world-leading work of rock star researcher Michelle Haber has improved children’s cancer survival rates by 85 per cent. She says one day soon, cancer will become a manageable disease. How will she do it?

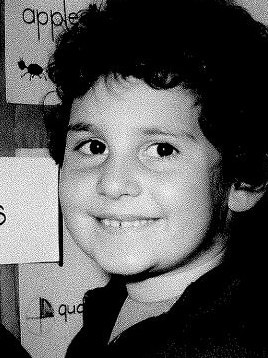

Vivian Rosati fingers the cross around her neck and speaks of faith and miracles. She is at the kitchen table of her home in Sydney’s North Ryde when her 15-year-old son Jack bounces home from school with a grin.

He’s hatching a plan to go mountain biking with his mates. “It’s his fave at the moment,” she says.

Jack then reels off a list of his other faves, from punching his boxing bag to cross-country running, skateboarding and surfing.

“Any sport really,” says Jack as he leaves the room to change out of his school uniform.

When he is gone Vivian falls silent and tears glisten in her eyes. “I’m so glad that mine is a happy story,” she says finally. “There are going to be a lot more happy stories like mine in the years to come. But Jack is my miracle.”

Five years ago, Vivian, a single mum, was watching her only child dying of cancer in front of her eyes. A year earlier Jack had been diagnosed with a benign brain tumour; then one morning he woke up vomiting and with a terrible headache. The tumour had returned – and this time it was cancerous and had spread to his spine. Jack was soon bedbound, unable to walk, eat, or see out of his right eye. It looked like he wasn’t going to make it.

“A group of medical staff took us into a room and gave us devastating news about Jack’s condition,” she recalls. “I remember sitting and looking down at the floor, not being able to face these doctors and professors – but my eyes were flooded with tears, I couldn’t see anything anyway.” The doctors also told her that as part of a new type of possible treatment, Jack’s biopsy was going to be examined by a fledgling program known as Zero at the Children’s Cancer Institute in Sydney, headed by a professor called Michelle Haber. “I just thought, ‘Yeah great, this program might save kids in the future but my kid is dying now’,’’ says Vivian.

But then three astonishing events unfolded together. Firstly, after three weeks of tests, the Zero program identified the specific genetic mutation – called BRAF V600E – that was driving the cancer growth in Jack. Secondly, there was a drug already available to target that rare mutation. And thirdly, from the moment Jack took the drug, he literally rose from what would have been his deathbed. “He regained his appetite, colour returned to his face, his headaches and body pain subsided,” Vivian recalls, as more tears are triggered by the memory. “A couple of weeks on he decided to pick up a tennis racquet and was playing tennis for the very first time. Not long after that, he was selected to represent his school team for cross-country.

“We were stunned – everyone was, from the neurosurgeon to the oncologists,” she says. “They could not believe it was the same kid.”

Vivian says that Jack’s miracle recovery was like “winning the lotto ticket”. I ask her who she thinks helped to give Jack that lotto ticket. “Michelle Haber,” she replies. “An incredible woman: smart, determined and unstoppable. She is the power behind this fight.”

Professor Michelle Haber is hardly a household name to most Australians, but speak to any parent who has experienced the trauma of having a child with cancer and they will almost certainly know who she is.

Haber, who for the past 20 years has been executive director of the Children’s Cancer Institute – the only institute wholly dedicated to the search for a cure – has become the public face of the fight against children’s cancer in Australia. But what makes her story so remarkable is that she and her institute are slowly but surely winning this historic battle. They are leading the world in new treatments and giving a new generation of parents and kids hope when once there was none. This is not a fast-sell medical spin offering false hope; the progressive breakthrough in the fight against childhood cancer is a reality backed by hard data.

“Back in the 1950s and 1960s cancer was virtually a death sentence for children,” says Professor Murray Norris, who has worked with Haber for more than 40 years. “It really didn’t matter what kind of cancer they had. But today the overall survival rate is up around 84 per cent, so we’ve come a long way over time. And we are absolutely at the forefront of what is being done internationally.”

Yet the story of the fight against children’s cancer in Australia has been far harder than these encouraging statistics might suggest. It has been a hardscrabble and often heartbreaking struggle, driven initially by desperate and good-hearted parents and backed by a small team of dedicated scientists. Progress has often been cursed by funding shortages and by lopsided victories where one type of children’s cancer is all-but conquered while other types are still certain killers.

And despite these huge strides, cancer is still the leading cause of childhood death from a disease in Australia, with around 1000 children and adolescents diagnosed each year, of which just under 200 will die. But Haber is the general who, with her team, is changing the course of this battle. She is masterminding what she believes will one day be a complete victory over children’s cancer. In doing so, she has caught the attention of the medical world.

“She is incredibly well known globally,” says Professor Andy Pearson, a former professor of paediatric oncology at Cancer Research UK, the world’s largest independent cancer research organisation. “Michelle Haber is one of the leading scientists in children’s cancer research in the world. She has led many innovations in research and one of her great strengths is that her research has a very direct and immediate benefit for children with cancer,” he says.

Haber certainly doesn’t look like the stereotypical nerdy scientist. On the day we meet in her office at the Children’s Cancer Institute she is dressed immaculately, with a pearl necklace and earrings. She speaks quickly and confidently, like someone who knows her subject backwards. Within minutes you get an inkling why so many parents of sick kids describe her as “a force of nature”.

“When I look at how far we have come, it makes me so proud and I think to myself, ‘What a journey’,” she says. “And yet every time I hear the stories of the parents and the children who are still not making it, I realise that we still have such a long way to go.”

Jack Kasses remembers the days when there was nowhere to go for parents when their children were diagnosed with cancer. “My little girl Helen was put into that building down there,” says Kasses as he stands on his balcony in Sydney’s Little Bay and points at an old building which was once a part of the former Prince Henry Hospital. He has never moved from Little Bay since he rushed his sick daughter there in 1975. “She was just like a lifeless body lying in bed and I was convinced she was going to die,” he says. “She was just six years old.”

In the 1970s the Kasses family were running several shops near Bundaberg in Queensland when Helen suddenly became ill. “I didn’t even know that kids could get cancer and I had no idea that there was a thing called leukaemia,” says Kasses, now 83. They took Helen to Sydney to seek the best possible care in the hope that somehow she might pull through.

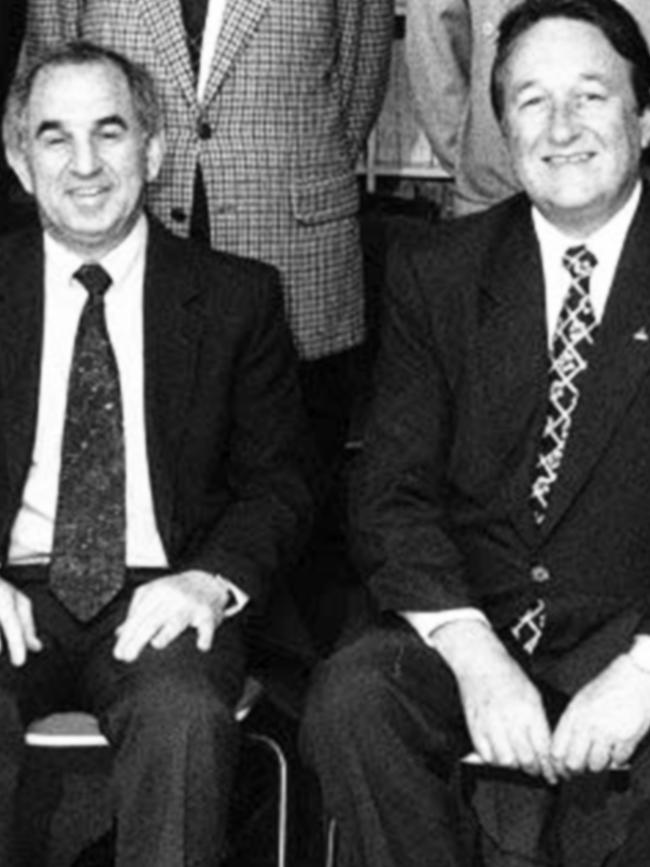

“In those days nearly all the children with cancer died, and in the same week that Helen was diagnosed, a little boy called Robbie was also diagnosed,” Jack recalls. He and Robbie’s father, John Lough, would hang outside the hospital together, talking. They became close friends. One day they had a conversation that would change the outlook for all children with cancer in the country.

Jack recalls: “John said to me, ‘We’ve really got to help these doctors. We’ve got to help them to do more research, to get a more scientific understanding of what children’s cancer is and how to cure it’.”

The two fathers were not rich but they resolved to launch a fundraising drive to get money to set up Australia’s first children’s cancer research laboratory. Both were members of Apex Clubs, and they pushed hard to harness the resources of the Apex national network to raise funds around the country for their vision. The campaign attracted the support of advertising guru John Singleton, who devised the campaign for free with the slogan: “Some kids make it, some kids don’t. Help a kid make it.”

The slogan was all too true. Jack’s daughter Helen did make it, and today works as a teacher in Sydney, although she still suffers side-effects from treatments she received. But John Lough’s son, two-year-old Robbie, succumbed to his cancer. The two dads forged ahead regardless. The fundraising campaign for kid’s cancer became a juggernaut, raising an astonishing $1.3 million – close to $8 million in today’s money.

In 1976 the money raised by the two fathers led to the opening of the Children’s Leukaemia and Cancer Foundation in Sydney, the body that would later become the Children’s Cancer Institute. “What separated this laboratory from almost any other globally was that it was built not by governments seeking re-election or by philanthropists seeking recognition but by families impacted by the disease,” says Haber. “And we never ever felt that the unit was anything other than a dream and goal of those two dads and the others that joined it.”

Eight years later, in 1984, the centre appointed its inaugural postdoctoral scientist. “We had no idea on that day that we had also appointed a visionary – someone who could help make our dream of helping defeat childhood cancer a reality,” says Kasses. “But we had. Michelle Haber turned out to be that person.”

There was no preordained pathway to the career that Haber eventually chose. There were no doctors in her family; her Jewish parents were Ten Pound Poms who emigrated from Liverpool when she was five years old. Her mother raised three children while her father, a linguist, became vice-principal of Mount Scopus College in Melbourne and then the principal of Moriah College in Sydney.

“It was never overtly stated, but our parents had great expectations of us,” recalls Haber. “[They thought] if we worked hard and applied ourselves we would be fabulous.”

Haber studied English, French and Hebrew in her final year of school, as well as maths and science. She deliberately chose school subjects she thought would be fun rather than useful because she imagined that, like her mother, she would soon get married and would have to give up her career to raise a family.

But that script didn’t pan out. She chose to do a clinical psychology degree at the University of NSW, winning a University Medal for it, before swapping to start a PhD in animal learning behaviour. Yet none of this captured Haber’s imagination. She was at a loss about what to do. “I thought, ‘Can I do something that will make a difference?’” she recalls. One day she was staring at the list of floors in a hospital when she saw the word pathology. “I thought that sounded interesting so I literally went up to the fourth floor and I said, ‘Is there someone I could speak to about doing a PhD here?’”

At her first lecture of the pathology course, she sat down next to a third-year student named Paul Haber. That was in 1979. They have now been married for 42 years, and have three children. Paul currently heads the Addiction Unit at Sydney’s Royal Prince Alfred Hospital.

Michelle Haber by then had decided that medical research was going to be her field, but what sort of research?

She and Paul went to Israel for three months in 1982 where she did research into Molecular Virology in Jerusalem. While she was in Israel she was contacted by her thesis supervisor, Professor Bernard Stewart, who said he was going to be the inaugural director of the fledgling Children’s Cancer Institute in Sydney and would Haber be his first scientist?

Just after she returned to Sydney, Haber experienced a day that changed her life forever. “There was an official launch of the new laboratories and oncologist Professor Darcy O’Gorman Hughes was giving a speech. He said, ‘Would all the children who have survived childhood cancer please stand up’.” As Haber recounts the story, her voice wavers and tears well in her eyes. “Then this forest of children stood up. And I knew that 15 years earlier none of them would have been alive. But they were alive, and they stood up, and I thought, ‘This is the future. This is going to be my career’.”

Haber started at the fledgling institute in 1984 alongside two other scientists, Professor Murray Norris and Professor Maria Kavallaris. All three of them have now worked together for 40 years, pushing and probing for breakthroughs.

The first came in 1996 when the institute’s researchers made the world-first discovery that the treatment of a type of children’s cancer called neuroblastoma was failing because it was linked to a drug-resistant protein. This opened the door for a host of new treatment strategies.

Then in 1999 the institute developed a huge breakthrough in the treatment of the most common childhood cancer, Acute Lymphoblastic Leukaemia (ALL). One quarter of all children with ALL were relapsing after treatment – but because it was impossible to know which child would relapse, all kids received high levels of chemotherapy and radiotherapy, leaving many of them with lifelong side-effects such as heart disease and infertility.

Haber’s team asked themselves, what if there was a way to predict which kids would relapse and which would not? They worked with oncologists at the Kids Cancer Centre at Sydney Children’s Hospital to develop a test that could identify the risk of relapse, allowing those kids who were at high risk of relapse to receive intensive therapy earlier while sparing those kids who were not at risk of relapse. In a ten-year trial that ran until 2011, the survival rate for kids with high-risk ALL doubled from 35 per cent to 70 per cent. “I remember thinking when I saw that figure that we were really making a difference and that the motto – ‘To cure every child with cancer’ – was no longer aspirational but possible,” Haber says.

Then in 2005, one of the institute’s scientists, Professor Richard Lock, developed the first patient-derived animal models for cancer, known as the PDX model, in which physical samples of a child’s actual cancer are grown in a mouse model, allowing scientists to quickly test different drugs and treatments on them to see which might work. Haber says this was a “game-changer” because it allowed for unlimited testing of new therapies for children’s cancer.

In the most crucial breakthrough so far, Haber read a scientific paper in 2010 that described a small study of 70 adults with cancer where the scientists tested their genes for responsiveness to particular drugs. “Knowing that the challenge in finding the right treatment for every child is that every child and every cancer is different, I thought we could do this with kids and we can do this better,” says Haber. “I got the team together and said, ‘What if we can test every child with cancer for cells that express a high sensitivity to a particular drug – effectively finding a drug that will specifically kill that child’s cancer and only that child’s cancer?’”

Haber’s idea was a eureka moment for the field of childhood cancer, allowing for the genetics of tumours to be tested for clues about what is driving the cancer in that particular child and how it might best be treated. In other words, every Australian child with high-risk cancer was given the opportunity to enrol in a personalised medicine program to study the genes of their particular cancer, with the aim of identifying a targeted treatment. Using this method the institute in 2015 launched the Zero Childhood Cancer Program – the one that saved the life of Jack, Vivian Rosati’s teenage son. The program now includes every children’s hospital in Australia as well as 22 national and international research partners.

In 2017, a three-year national clinical trial for the Zero program opened; it found that it was possible to explain the molecular basis of 90 per cent of cases of children with high-risk cancer, opening the way for more effective drugs to be developed. The findings, published in the scientific journal Nature, made news in cancer research centres around the world.

“Of the first 250 children with high-risk cancer who were analysed on the Zero program and then received the recommended personalised treatment for their genetic change, 70 per cent of them either had a complete or a partial remission, or the growth of their tumour had stabilised,” says Haber.

But these hard-won gains in the battleagainst childhood cancer are uneven. Some kids just never get a fighting chance.

Mary-Ellen Rogers ushers me into her Sydney home past a series of painted rocks in the garden. One written in purple paint says: “Amity we love you.” Another reads: “Funny and caring.” In the garden is a brass plaque that reads: “Amity Margaret Rogers: Our funny, joyous, clever, loving, spirited daughter … desperately missed by her ‘best family forever,’ wrapped in eternal joy, our darling Amity.”

Amity was almost five years old when her parents, Mary-Ellen and Jackson, noticed that she was no longer her usual bubbly self. Her behaviour became more erratic but they thought the problem was psychological rather than physical until one day a doctor suggested that Amity have a CT brain scan. “The doctor came back to me and said, ‘We need to talk,’” recalls Mary-Ellen. “Then he wanted it to be in a private room, then he said, ‘I need your husband to bring a support person.’ So I knew. I thought, ‘Right, I get it, she’s going to go’.”

Amity had the most aggressive childhood brain cancer possible. Known as diffuse intrinsic pontine glioma, or DIPG, the tumour occurs in the brain stem and is always fatal. It kills around 20 Australian children a year.

For the next 18 months, as Amity’s body slowly stopped functioning, her parents and her two brothers did whatever they could to enjoy the time they had left together. “Who knows what is wrong and what is right to do in that situation, but we all just tried to live as normal a life as possible,” Mary-Ellen says. “She had her sixth birthday in September 2017, and I’d say October was the beginning of her decline. By mid-November she was losing the ability to move, and she died on the 11th of January.”

Shortly before Amity died Mary-Ellen said they learned that Haber’s institute had set up a tumour bank, to allow parents to donate their child’s brain tumour so it could be grown in the lab and studied to increase the potential for a future cure. For Mary-Ellen, it was an easy decision. “We were like, absolutely we will donate the tumour – for a couple of reasons. One, we liked the idea of burying her without the tumour, and Jackson likes the fact that the tumour is probably being tortured in the laboratory. But secondly, what progress is there going to be for other children if we don’t do that? Also, Amity said at a very young age that she wanted to be a scientist and so we figured, well, this is her small way of contributing.”

After Amity’s death, Mary-Ellen started attending fundraisers for the institute, where she got to know Haber. “She is pretty much always there at those functions and she is a powerhouse. She can do science but she can also do people – she’s a fabulous communicator. I can see why she’s been in that role for so long.”

In February, another mother, Kathryn Wakelin, gave a speech at an institute event about losing her eight-year-old son Levi to DIPG, the same disease that took Amity’s life. After Levi’s death, the Wakelin family helped to set up Levi’s Project, a research project run by Haber’s institute that has so far raised $2.6 million for DIPG research. “I spoke [at the event] about our journey as a family through illness and death and bereavement, and how it changes you and your outlook on life,” Wakelin recalls. As she was speaking, she noticed that Haber, who was in the audience, was crying. “It was amazing,” Wakelin recalls. “She had tears in her eyes and it was not the first time she had heard our story. That’s Michelle for you. She has genuine compassion. It’s not just her job but her mission. You can feel it. And it makes parents like us want to be a part of that mission.”

Now Haber and her institute are embarking on their most ambitious move yet. They want to expand their successful Zero program beyond children with high-risk cancers to include all children in Australia with any type of cancer. So for the first time, every child diagnosed with cancer in Australia will have the chance to access the personalised medicine that Haber and her team have designed. That will occur by the end of this year, and in 2025 the institute’s new home, the country’s first Children’s Comprehensive Cancer Centre, is due to open at the Sydney Children’s Hospital in Randwick.

Haber insists that she is not being a dreamer when she says that she now believes childhood cancer in Australia will be conquered within a generation. “I don’t see that as aspirational, I see that as reality,” she says. “Because of medical research we’ve gone from zero survival to 70 per cent to 80 per cent and 85 per cent. One day we will get to zero children dying of cancer and there will be drugs available that will make this a chronic, manageable disease,” she says.

She breaks into a smile and fixes her eyes on me. “That is the future.”

To support the Children’s Cancer Institute’s work, you can donate at ccia.support/research

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout