Canberra’s Mr Fluffy asbestos disaster still spreads misery

Not all disasters are equal. Some are wet and wild, some are cyclonic or fiery. The disaster that has settled over Canberra can’t be seen or smelt, but it is insidious.

Not all disasters are equal. Some are wet and wild, with torrents of rain falling at unprecedented levels for days, fracturing lives and livelihoods. Some are cyclonic. Some are so hot and fiery you can still smell their devastation long after their fires have been extinguished.

The disaster that has settled over Canberra is insidious. There is no specific day on which it began and not even an official date, let alone a monument, to commemorate its casualties. As a calamity it is largely imperceptible. You cannot smell it or feel it, and the substance at its root, a minuscule white fibre that can be deadly when inhaled, is hard to see. But its impact has been enormous.

Nearly 1000 homes have been destroyed as a result of it, their residents not just uprooted but left with a lingering worry that they may yet become fatally ill from living in a home where loose fill asbestos was used for insulation. Their misery is enduring and largely misunderstood, even within their own city. But what really distinguishes the disaster that has befallen them is that while many others are natural, this one was man-made. And, given the warnings sounded about it long ago, it was also preventable.

Marion McConnell saw the advertisement in the early 1970s. She and her husband Brian had moved into their first home, a just-completed four-bedroom house in Higgins, a bushy new Canberra suburb whose winding streets were named after judges. “It was in a good spot, the kids could walk to school, we had nice neighbours,” says McConnell, now 76. The garden still needed work, a project the couple would go on to happily embrace for decades. “But otherwise it was ready to go. We just had to put the insulation in.”

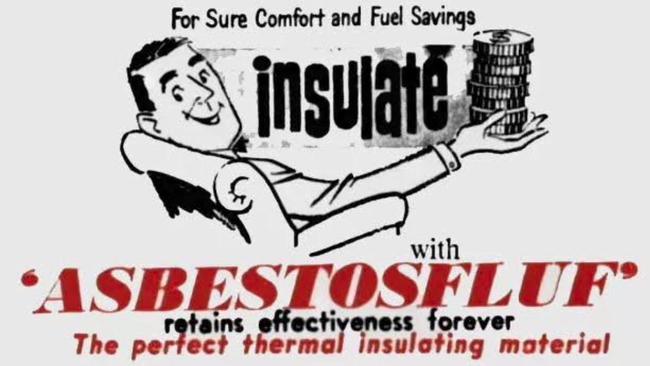

One option that caught McConnell’s attention was Asbestosfluf, later known as Mr Fluffy, a loose fill product made of raw, crushed asbestos. “The perfect thermal insulating material”, it had “much greater insulating and sound absorbing properties than equivalent thickness of any other type of material”, according to a local newspaper ad, which also claimed the product was CSIRO-tested and approved. (Despite extensive searches, the CSIRO today can find no proof of this.) Costing less than $100 for an average house, it was also efficient to apply, sprayed into ceiling cavities “quickly and cleanly”.

“A few of our neighbours got together and we decided that this asbestos insulation was a good insulator and fire retardant, and we went for it,” says McConnell. But the installation was not as tidy as promised. “The guy came and blew it in, and there was stuff all over the garden,” she says. “He didn’t have any protection. He didn’t have a mask on.”

The man worked for Dirk Jansen, a local business operator who had been touting Asbestosfluf since 1968, offering discounts to neighbours and storing the bags of fine, white material under his Lyons home. “We used to romp on it and the fibres in the air were like a dust storm,” one of Jansen’s eight children would tell the ABC years later. A Jansen son was among those who would blow the product into Canberra roofs, where it was allowed to settle across battens and ceilings and behind cornices, setting off a chain of events that would continue to have devastating consequences decades later. Not that McConnell had any concerns back then. “We never for one moment thought we were putting stuff in our ceiling that was dangerous.”

In reality, the kind of work that was being done on her home had been causing disquiet for years. Asbestos is a health risk when it is inhaled as a fine dust. Its disastrous reputation in Australia has been earned largely from building materials that were used in many premises and pose less of a threat if uncut and undisturbed. What makes Asbestosfluf so potent is that it is composed entirely of crushed asbestos. Its microscopic fibres are easily airborne and able to be trapped in a person’s lungs.

Unbeknown to the McConnells and their neighbours, a leading industrial hygienist, Gersh Major, had been alarmed about the product as early as 1968, after observing two of Jansen’s men apply it. “The principle associated with this work is quite simple: a centrifugal fan mounted in a small motor truck blows asbestos fibre through a 2½ inch diameter p.v.c. hose into the roof space of a house so that the ceiling is covered with a layer of ‘asbestos fluff’,” Major reported to the federal health department. About 115kg went into each house. One man used his hands to scoop the asbestos into a hopper, while the other worked from the roof space directing the hose. “Both men are clearly exposed to excessive asbestos dust and should take great care to minimise this exposure,” wrote Major. “Indeed it is unwise for them to be working with this material whilst suitable substitutes… are available.”

Beyond the immediate safety of Jansen’s workers, Major’s greatest concern was with the work itself. “Some thought should be given to whether D Jansen and Co Pty Ltd should be dissuaded or even prevented from using asbestos as insulation material in houses. Not only are men unnecessarily exposed to a harmful substance in the course of their work, which is against the best public health practices, but there is some evidence that community exposure to asbestos is undesirable.” His final words were even more portentous: “With the present demand for insulation, Canberra may become a large market for asbestos insulation with many people in the community exposed because some asbestos will be carried out of the roof space by air currents.”

Six months later, in December 1968, Major’s report was forwarded by the acting director of the local branch of the federal Department of Health, Arthur Spears, to the director of the Department of Works, who had requested the initial report. “The results of our investigations,” Spears wrote, “have disclosed what appears to be a serious exposure to asbestos dust. In view of (the) harmful nature of this substance the use of asbestos fluff for the purpose of insulating should be discontinued.”

Jansen, however, would continue to provide Asbestosfluf for another 11 years, pumping his product into hundreds of homes in Canberra and NSW, and granting the national capital an unenviable status: nowhere in the world, it seems, has loose fill asbestos been installed for so long in so many homes.

“As far as we can ascertain nothing happened after that report,” Dr Sue Packer says decades after Major’s warnings were sounded. “As far as I know it was filed.” A retired paediatrician and the 2019 senior Australian of the Year, Packer spent much of her career advocating for the rights of children. But it is asbestos – about whose dangers she was already aware in 1966, when she graduated from medical school – and its terrible local legacy that have taken up so much of her recent time.

“Virtually all those houses were in established parts of Canberra,” says Packer, chair of the community and expert reference group that has been advising the ACT Government on the issue. “They were nice houses. They were mostly not first home buyers. They were bought by independent owners, proud of looking after their families so well. They had never had to ask the government for any help in any other part of their lives.” Yet decades would pass before many learnt they were living in a time bomb.

Asbestos controls were introduced in the ACT in 1979. A decade or so later, when the dangers of the product were more widely understood, 65,000 homes built in Canberra before 1982 were surveyed. A register of the 1023 properties found to have loose fill asbestos insulation was compiled.

Between 1989 and 1993, the federal government and the newly created ACT government jointly funded a program to have those homes cleaned of all visible and accessible traces of the product, mostly from roof cavities that were then sealed. Although the homes were subsequently declared fit to live in, there were concerns even then that fibres had also fallen down wall cavities.

That fear became real in 2011 when a house in Downer was found to have been missed in the removal program. The residence was bought by the ACT government, forensically deconstructed and then demolished. It was found to be so contaminated that asbestos fibres had migrated through the house, into the living area, the airconditioning ducts and through the sub flooring.

The find was catastrophic. “Because of the migration paths that exist in homes of that era, no cleaning process was ever going to get rid of all the fibres,” says Bruce Fitzgerald, who manages the ACT’s Asbestos Response Taskforce. The only way to solve the risk was to demolish every home in which loose fill asbestos was known to have been installed. Thousands of Canberrans were about to have their lives upturned.

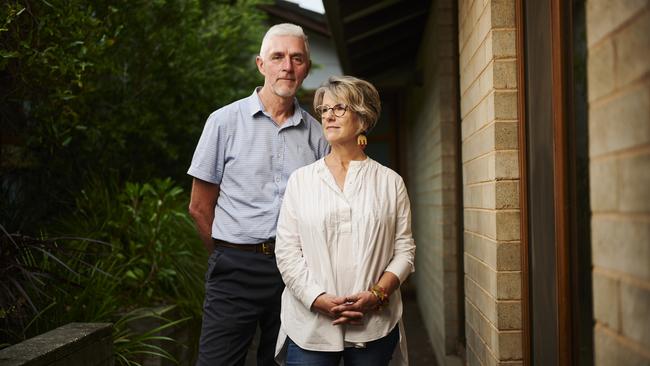

Until they received a letter from the ACT government in February 2014 alerting them to the Downer house findings, Chris Redmond and Barbara Walsh were not concerned that the home in which they had raised their three children, a 1950s residence on a sunny quarter acre in O’Connor, was a Mr Fluffy house. “I thought it was a warning letter rather than saying to you specifically you need to be aware there might be a potential risk of living there,” says Redmond of the note, which was addressed generically to “the home owner”. “Our neighbour had told us that there had been asbestos in the ceiling but it had been removed [under previous owners] in the early ’80s or 90s.”

To be abundantly cautious, the couple organised another assessment. To their astonishment they learnt that fibres had migrated down their walls, collecting in an area under the house that Redmond had accessed multiple times, in a hall cupboard where they stored the family’s bike helmets, and was seeping out of the cornices. “And it hit me,” says Walsh, “that my God, we might be financially ruined, we might have long-lasting health impacts, and we might have consigned our kids to get sick later in their lives.”

Eight months on, her concerns were reinforced when the ACT government announced it would buy back the 1000-odd properties on the Mr Fluffy register, supported by a $1 billion federal loan. The homes would be surrendered to the ACT government and demolished, and former owners offered first right of refusal to buy back the remediated blocks. Loose fill asbestos would finally be removed from the national capital. “We saw it as being basically a lifeline to move on and move on quickly,” says Walsh. “We didn’t want that to define us as being victims of the Mr Fluffy crisis. We thought it was important for our mental health more than anything else.”

In December that year, she and Redmond bought a house in Aranda. While renovating it they remained in their old home, celebrating one final family Christmas there but wary to not open the hall cupboard or invite any other guests, and alerting visiting tradesmen. “It was like having the old blood on the door,” says Redmond.

They sold their cherished home to the ACT government for just under $1 million. “I remember the paperwork,” Walsh says, “and it had this red stamp: ‘surrendered’.” When they moved out in March 2015, they left behind their beds, lounges and blinds, their bike helmets and boxes of old postcards and memorabilia. “We closed the door, paused in the back yard, said ‘It’s been great’, gave each other a hug and a kiss, took the dog and drove to the new place, bawling,” recalls Walsh.

While they have happily adapted to their new neighbourhood, even with the buy-back at market rates the process has still cost them several hundred thousand dollars. “The whole thing was so intense,” says Redmond, an otherwise calm man who cries several times, to his own surprise, when recalling the transition away from their old established lives and the associated emotional and financial upheaval. “There’s something about it that still brings me undone.”

Walsh is still upset, years on, at the memory of seeing their old block of land days after the house was demolished, when all that remained were “danger” signs. “It was erased like that,” she says. “I just couldn’t believe all of those years of work and all of those memories, there wasn’t even a pile left. They’d taken everything away.”

While the path that led to the crisis was insidious, the solution was visibly jarring. Neighbourhoods changed as residents moved out, homes were destroyed, and streetscapes became pocked with empty blocks or with bright new homes that stood out among otherwise cohesive stretches of Mr Fluffy-era residences.

“Once this problem was identified, none of these houses was insurable and none was saleable unless somebody was prepared to buy it to knock it down and build it again,” says Packer. Elderly residents who assumed they were in their home forever suddenly had to bid for new places at auction. Despite being offered market rates, many found they could not afford to buy back the remediated land as well as rebuild, and so opted to relocate. “It’s the position these home owners are left in,” says Packer of the futility that many have confronted, “that the core of their life is declared to be worse than useless, it’s hazardous.”

Lorraine Carvalho has experienced both sentiments. She and her husband Leo bought their Lyons home in 2003, a day before bushfires ripped through Canberra. They were given permission to gut it and renovate it extensively, but it was not until 2014, when an old neighbour knocked on their door, that they discovered its history. They were living in the former home of Dirk Jansen, who died in 2001. “We have no complaints with it being demolished… We just think it’s a terrible waste but it has to go. What we have a complaint with is that we were not given a choice,” says Carvalho, who has rejected the $985,000 offered for their home and land, when the replacement value for the home alone, she says, is $1.2 million. “I do feel trapped. I can afford to leave. I just refuse to leave on the grounds that they have set… We would lose too much money.”

Before the couple realised their home’s provenance, “this house would have given both of our children a house each. Now they can’t even buy one between them. I can’t make any money on this house. And the only people I can sell it to are the government or a developer… A lot of people say, ‘Well why are you holding on?’ And the first thing is it’s for money. Bloody oath it’s for money, because I put it [money] in here.”

So for now she and her husband remain at home, although the stigma of remaining in a Mr Fluffy house endures. “Some people won’t come here even though they know what we have done to the place,” says Carvalho, who believes her home’s extensive renovations have removed any health risks. “I even know somebody who came to visit and then went back home and his wife wouldn’t let him inside until he stripped and he threw his clothes in the rubbish.”

The Carvalhos’ is one of just 35 Mr Fluffy homes still standing, and eight of them have been acquired by the ACT government. The remainder continue to be privately owned for a variety of reasons, including mental health and marital issues that could be exacerbated by moving out now. Nearly 1000 buildings have been destroyed (several were lost in the 2003 bushfires), scattering their old residents in all directions.

“Everyone was sympathetic to the bushfire victims, everyone was fearful of the bushfire, but not with Mr Fluffy. There’s not that heartfelt sympathy for the upheaval,” says Geoffrey Rutledge, who heads the ACT’s Asbestos Response Taskforce. “There’s no anniversary date for the Mr Fluffy saga. There’s no citywide recognition and yet for the 1000 families not only did they lose their homes… for many they have still got in their minds that they climbed up in the roof as a kid; ‘when I turn 60 will I get affected by this?’ ”

Mesothelioma is an invariably fatal cancer that normally develops 10 to 50 years after exposure to asbestos. According to the ANU’s ACT Asbestos study, which began in 2015, the rate of mesothelioma in men living in Mr Fluffy homes is two-and-a-half times higher than for other men.

Statistically there is only likely to be a small impact in terms of overall public health. According to the Australian Institute of Health and Welfare, between 2012 and 2015 there were a total of 26 cases of mesothelioma among ACT men, a lower overall rate than, say, in WA. Perhaps three people will die from mesothelioma due to living in a Mr Fluffy house, according to Bruce Armstrong, one of the co-authors of a 2017 report into the cancer risks from these homes. But homes left standing would be uninsurable and there is no known way to safely eradicate the risk apart from demolition.

“Would I live in one of those houses? Probably not, because I would be subjecting myself to an unnecessary hazard any time someone came in and stirred up a bit of dust,” says Armstrong, emeritus professor at Sydney University’s school of public health. “In terms of actual health impacts, there’s clear evidence of mesothelioma occurring mainly in men as a result of living in Mr Fluffy homes,” he adds. “It was the men who did the renovations. If anyone got into the roof it was always the men.”

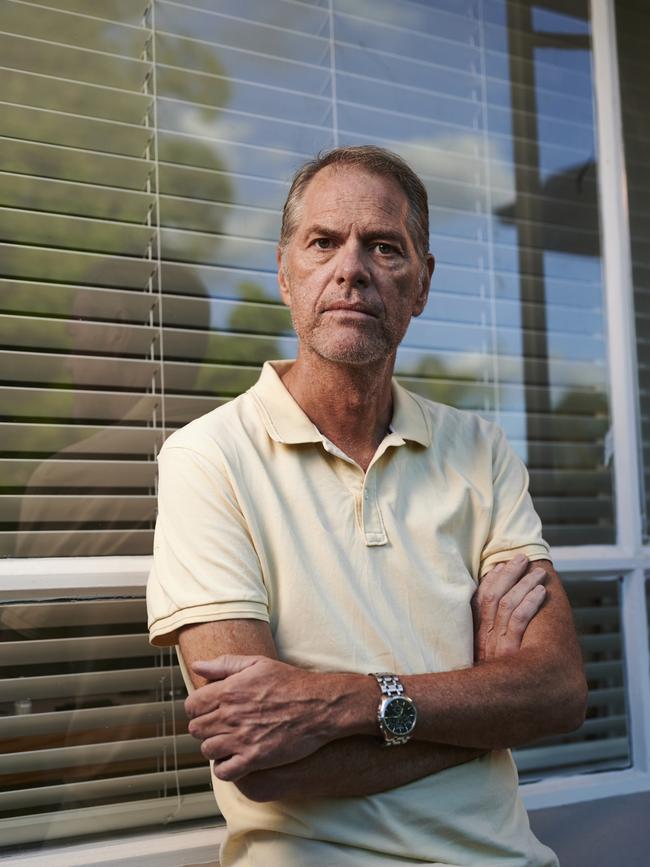

Bruce Wallner remembers the house his parents built in Campbell in the early 1960s, “playing while the house extensions were going on” around 1969, and the snowball fights with his three brothers using wads of loose fill asbestos that builders had left under a tarpaulin in the garage. He remembers the residue that later kept falling inside, to the consternation of his mother who “got sick of this dust running down on the kitchen benches and sink and she ended up putting foil over the fan to stop the dust”.

But it was not until the 1980s, when their house was audited, that they discovered that the dust was probably Asbestosfluf. Unbeknown to them, it had been pumped into their roof – the same space in which James, the youngest Wallner son, had later donned mask and gloves to help install insulation bats. “My theory is they had a builder doing the house, and the builder contracted Jansen to do the [initial] insulation,” Bruce says.

After the audit, mesh openings in some of the corners were covered in plastic film to secure the roof cavity. Later, in 1992, his parents moved out temporarily while the house was enveloped in plastic and the remnants of loose filled asbestos were vacuumed out.

After his mother died of lung cancer, Bruce’s father, who has also since died, sold the house in 2000. But the family’s connections to their old home did not end there. Last year, James thought he had pulled a muscle while playing golf. Anti-inflammatory medication did not stop the pain in his chest and by May he was becoming breathless. In July, just before he turned 54, he was diagnosed with mesothelioma.

“Someone makes up the stats and unfortunately in this case it’s me,” says James, a senior federal veterinary official whose suffering has been compounded by his difficulties accessing compensation. Unlike most people who develop mesothelioma, his exposure was not a result of his occupation. Late last year, the ACT government awarded him a one-off payment of about $250,000 to cover his medical expenses, and the federal and ACT governments have since begun looking at ways to support non-occupational victims.

Having lived and worked overseas for years, James is now largely confined to his Canberra home, where his quality of life has rapidly deteriorated. “If they need a poster boy for what the disease looks like, come and talk to my brother,” Bruce, 61, says passionately of his youngest sibling, who recently spent 10 days in a hospice. “He’s in excruciating pain all the time because he can’t draw breath… He spends a lot of time lying down. He has had to buy one of those electric reclining chairs just to get comfortable. His appetite has gone. He can’t drive because of the opiates. Even though he’s alive, in terms of the quality of his life he’s been transported 30 years in time to the very end of his life.”

The domestic disaster that has befallen Canberra is significant. Homes have been felled and lives interrupted. “It’s a very human story with loss of home and uncertainty,” says Sue Packer. “It affects so many people in so many different ways and some people will never get over that, and other people have moved on. But you’ve moved on with the knowledge that it may come back and bite you any time in the next 40 years.”

Why should the rest of Australia care about this? “It’s what went wrong in the first place to enable this to happen… So much we assume is OK because someone in authority has okayed it and we don’t take a level of responsibility for our own lives and our own decisions,” she says.

“How well do people cope with a completely unprecedented event of this sort?” wonders clinical psychologist Rob Gordon. “I know people who feel pretty sad about it but sold their home and moved somewhere else and started again, and others who just really became completely caught up in anger about how unfair it was and found it very hard to move on. If you have a bushfire it’s a completely natural event that no one has any control over. But it’s well documented that things to do with human malevolence or in this case stupidity or greed are far harder to accept.”

“It’s an emotional thing,” says longtime Canberra resident Marion McConnell, for whom the issue became very personal in 2014. On the day the ACT government announced its massive buy-back program, and decades after she had arranged to have Asbestosfluf pumped into the roof of her family home, her husband Brian was diagnosed with mesothelioma. In March 2014, the couple had moved out of their home of almost 40 years. Just over a year later, Brian died.

His widow now lives only 6km away, but in seven years she has never returned to the site on which their long-cherished family home used to stand. “It’s not just a house, bricks and mortar,” she says quietly. “This really was life and soul.”