Brian Cadd, veteran muso, still has that old magic

He’s 72, with a new album out and gigs galore. And Brian Cadd isn’t the only ageing rocker riding a late-career wave.

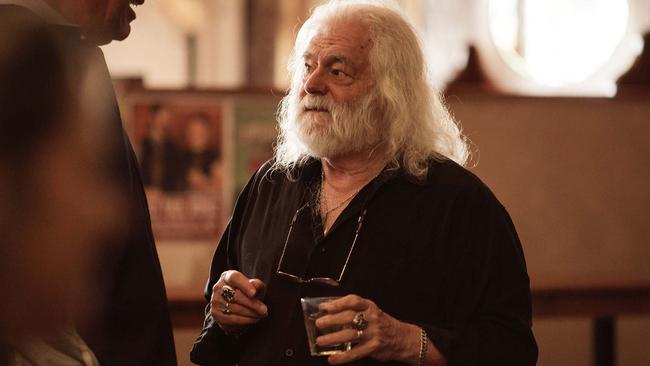

It’s 5pm on a Monday afternoon, so this must be Adelaide. Brian Cadd emerges from the elevator of his city hotel looking puffy-eyed, his snowy mane of hair cascading over his shoulders in search of a comb. This time yesterday he was in eastern Victoria playing to 10,000-plus people at an outdoor festival in the Alpine high country; tonight he’s in a tent playing to a couple of hundred punters, quite a few of them on the wrong side of 70 like Cadd himself. Taking his seat in a rental car with the rest of his band, he rubs his eyes and admits croakily: “It gets to the point where the afternoon nap doesn’t work anymore.”

It’s nearly 60 years since Cadd played his first pub gig as a 14-year-old in Perth, and nearly half a century since his most famous song, A Little Ray of Sunshine, became a hit. But at 72 he’s just released the first ARIA Top 10 album he’s had in more than 40 years, so here we are, at the tail-end of a three-month tour that has crisscrossed the eastern half of Australia, at one point covering three states in one week. Cadd flew in this morning with his band after playing a back-to-back run of four gigs in Victoria; their gear came overland thanks to their road manager who pulled a 900km overnighter.

A younger band might endure this kind of schedule by resorting to sexual debauchery and hotel-trashing. This outfit is more likely to have a quick lie-down. Guitarist Tony Naylor, a silver-haired 70-year-old, has been playing with Cadd for 47 years; drummer Geoff Cox is of similar vintage. “We don’t party quite like we used to,” admits Naylor. “The recovery period is much longer these days.” In his 20s, Naylor played guitar with Avalanche, a big-hair 1970s hard rock band whose members once drove their truck nonstop from Brisbane to Melbourne with half of them lying asleep on the amps and instrument cases. These days, he notes thankfully, rock’n’roll is more of a fly-in-fly-out business.

The venue tonight is a replica 1920s cabaret Spiegeltent erected in Rundle Park for the Adelaide Fringe Festival, which has programmed a series of 7pm concerts curiously scheduled to last only an hour, prompting speculation about whether anyone will actually turn up. Arriving at the grounds, the band seek directions to the “green room” and are led to a prefab demountable equipped with two trestle tables, a fold-up chair, a sink and an electric kettle. Cadd surveys its cramped, bare interior and asks hopefully if a drinks rider is provided. “Well, it’s the Fringe Festival, so normally there isn’t,” apologises a staffer, offering to go to the bar. “Put me down for a large white,” says Cadd, who had the foresight to bring along a bottle of Johnny Walker. He takes a seat and offers a wry smile. “This is the romance of the road — it goes from the sublime to the ridiculous.”

A dressing room mirror would’ve been handy, he admits, although it becomes clear that Cadd’s backstage requirements are minimal. His grizzled Wild Bill Hickok look is much the same onstage or off: embroidered western shirt, tasselled suede waistcoat, chunky Native American turquoise rings, cowboy hats, flowing white beard. The band barely needs rehearsing, given that two of them have been playing with him since Justin Bieber’s dad was in nappies. The booking agent for this tour, Frank Stivala of Premier Artists in Melbourne, is the same agent Cadd used in the 1970s.

Back then Cadd was an elfin piano-man in the mode of Elton John, with a dash of Leon Russell’s Tulsa country-soul. Over the intervening years he’s been a jingle writer, a television and movie composer, an aspiring pop star in Los Angeles, a record producer in Nashville, a studio owner, a music publisher and an indefatigable tunesmith selling songs to the Pointer Sisters, Joe Cocker and a host of others. It’s a career successful enough to have given him a trans-Pacific lifestyle split these days between upstate New York and Byron Bay, suggesting he doesn’t need to be playing five gigs a week to make ends meet.

“Probably not,” he agrees. “But all of us who started in the ’60s, even including Keith Richards, still seem to be going and going and going, even though we say ‘This is definitely the last time’. I’ve been mulling that over myself. I’m 72 and I say to myself that I won’t do it anymore, but last night there were somewhere between 10- and 15,000 people in the audience. You’re up there on stage and they’re all singing one of your songs in unison and you say to yourself: ‘This is why I’m doing it’.”

Later that week, Cadd’s old mate Russell Morris (b. 1948) was due to arrive in Adelaide for a series of gigs to promote a new album he’s just released, half a century since his first hit The Real Thing. Meanwhile, in Melbourne, Ross Wilson of Daddy Cool fame (b. 1947) could be found onstage at the Palms at Crown, and Joe Camilleri (b. 1948) was reuniting his old band Jo Jo Zep & The Falcons for a one-off concert ahead of a national tour by his other veteran outfit The Black Sorrows. And if you missed those shows, fear not, because you can soon catch all these performers together in one concert, along with 68-year-old John Paul Young and that young whippersnapper Kate Ceberano (b. 1966), as part of the APIA Good Times Tour, a two-hour rock nostalgia package hitting 16 cities over 30 days in May and June.

That old adage about the road going on forever has turned out to be true for many a veteran rock act from the halcyon ’60s and ’70s. Cadd still performs regularly as a double act with Morris, who he first met as a teenager in Beatles-era Melbourne, and also with Glenn Shorrock, who sang A Little Ray of Sunshine back in 1970 when they were both in the band Axiom. Shorrock turns 75 in June and is enjoying a late-career financial windfall since the US supermarket chain Walmart licensed his old Little River Band hit, Help Is On Its Way, for a national advertising campaign.

“You can’t tell me Shorrock needs the money,” chuckles Cadd as he nurses his chardonnay in the Fringe Festival donga. “There’s no reason for him to play live other than he likes it. In the end, it’s all about adrenalin. It doesn’t matter if you’re feeling bad just before you go on. You might have a headache, your back might be hurting, your knees might feel crook, but then you hear them announce your name, you go out onstage and — dada! — you’re instantly 28 years old again and nothing hurts anymore.”

Outside, drummer Geoff “Coxy” Cox is sitting on a stool chugging back a pre-performance beer. At 69, Cox has the barrel-chested build and handlebar moustache of a publican, which he was for many years. Better known these days as the host of Coxy’s Big Break on the Seven Network, his pedigree with Cadd goes back to 1971, when he played on the debut album that yielded the evergreen ballad Ginger Man. He was the drummer on the 1974 US tour when Cadd played to 20 million American television viewers on Don Kirshner’s Rock Concert. He was also the drummer six weeks ago when they played out back of the Star Hotel in Gundagai in 40-degree heat. “Shit it was hot,” Cox recalls. “The soundcheck was murder, and that was at 5 o’clock. At the end of it, packing up my drums, I actually sat down and drank three 600ml bottles of water. When I got home my wife said, ‘Are you all right? You look pale’. I can tell you this, it’s got me raging to go to the gym.”

So why do it? “Well, Nayls and I have been with Caddy since the first album,” says Cox. “We’re great mates.” Plus, there are moments in music that can only happen onstage, such as the strange scene that unfolded yesterday as they played at the Brighter Days Festival. “This girl in the front row — well, she was probably in her 40s, actually — she was loving it,” Cox recalls. “There’s this huge crowd and she’s right down at the front of the stage really getting into it. Then Brian launched into Ginger Man and suddenly there were tears streaming down her face. It was horrible in a way; you could see she was seriously upset about something. I couldn’t stop looking at her while we were playing, wondering what was going through her head. Things like that happen and you want to know why; what is it about that song that caused that?”

For those who like to wallow in the music of their youth, this past summer has been a long, luxurious mudbath of nostalgia. The 73-year-old British crooner Bryan Ferry toured the nation’s wineries and stadiums accompanied by three 1970s-era Australian rock acts — The Models, I’m Talking and Stephen Cummings; leather-suited 60-something Suzi Quatro returned to Australia for the 32nd time, playing with five reconstituted Australian rock bands from the Countdown years; John Paul Young hit the road for a series of concerts playing three decades of hits by famed Australian songwriters Vanda & Young; and Jimmy Barnes was out there with vintage rockers Diesel, Joan Jett and Richard Clapton.

Frank Stivala, a founder of Premier Artists booking agency in 1973 and now its managing director, points out that rock’n’roll has always had an oldies circuit, and artists like Cadd, Russell Morris and Ross Wilson never actually stopped working. Their radio hits gave them an audience that crosses generations, and their roots in the heavy-touring 1970s made them seasoned performers. “They can play through a tin box and still sound good because they’re experienced, they know their instruments and they know how to work an audience,” says the famously gruff Stivala. “I’ve been booking Brian on and off for decades; you don’t just say, ‘F… off, your use-by date is up’. Why stop? Frank Sinatra sang until he was 80.”

The current nostalgia boom, however, is also a peculiarly millennial by-product of technology and demographics. As internet file-sharing and streaming have drastically reduced the royalties musicians earn from their recordings, live performing has become their most stable income. At the same time, promoters discovered that empty-nest baby boomers were an underexploited market and began packaging their old favourites into multi-artist concert tours, a phenomenon kickstarted in Australia by the 2002 Long Way To The Top tour devised by veteran rocker Billy Thorpe. Featuring 26 Australian performers from the 1950s to the 1980s playing in sports arenas, that tour grossed more than $10 million and went on to run for 10 years, even after Thorpie himself had passed on to the great gig in the sky.

“That was an absolute watershed,” says Amanda Pelman, who co-produced Long Way To The Top and along the way became Cadd’s significant other during the inaugural tour. “Those artists were not touring at anywhere near that scale, they were all doing the RSL run, and Billy recognised that the market was there. It resurrected a lot of careers.” Today the Day On The Green concerts feature similar line-ups touring wineries and urban parks, and the Red Hot Summer Tours have taken the same idea to regional concert halls. In these shows, rock’n’roll is both a nostalgia event and a family affair, as middle-aged couples take along teenagers who have grown up streaming the entire history of pop music on their phone.

“Humans by nature are nostalgic,” muses Russell Morris, who now performs 60-70 shows a year and is busier than he’s been in decades. “For most people the past is more romantic than where you are at the moment.” Morris performed on those Long Way To The Top tours, he’s on the APIA Good Times Tour this winter and then he’ll jump onto a Beatles tribute show with Shorrock, JPY and Doug Parkinson in August. But he’s also wary of getting pigeonholed as an oldies act — his recent career revival went into overdrive after he recorded a blues album, Sharkmouth, steeped in Australian folklore. A major departure for him, it was rejected by every major record company but went on to sell more than 100,000 copies.

“I’m certainly not ashamed of what I’ve done in the past, but if you want to break that mould you have to learn to dance a new dance, and a lot of my contemporaries struggle to do that,” he says. “The nostalgia thing is going really well, people are turning out in droves to see them. But like the ’50s artists, we can end up like lemmings walking ourselves off a cliff in the end.”

Cadd, likewise, is adroitly pitching his new album, Silver City, as an “Americana” recording, with one eye on the US market. Recorded in Nashville, it features a cover shot of him looking like a Wild West gravedigger, and last year he and Pelman moved to Woodstock in upstate New York to pursue its release there. But he also knows that not playing his hits would be seen as a betrayal by his audience; he once did a tour in which he packed all the old tunes into an end-of-concert medley, in the process suffering such a backlash from the punters that some asked for refunds.

“I say it often because I believe it: one of the things that happens when we play is that the audience, the great majority of whom in my case are aged 40 to death, relive their youth. You look down in the audience and there’s a couple there, they’re aged 58 and 62, they’re sitting there and holding hands and you start playing Little Ray Of Sunshine, they look at each other and at that point they’re in their twenties again, and they’re holding their baby. And I get quite emotional about that because it’s an enormously powerful thing to be able to do, and it’s not treated lightly… That’s a lot of the reason they’re there — my ability to touch them and help them touch those markers in their lives and relive them during that two hours.”

At 7pm sharp, Cadd takes the stage of the Spiegeltent, standing at an electric piano with a full tumbler of scotch in one hand and his five-piece band behind him. He hits them with a new song first, then it’s straight into the first of the big hits: Arkansas Grass from 1969. Misty smiles pass across the faces of a couple of senior citizens in the front row, possibly due to an AM transistor radio flashback. “They told me before we went on that we had 17,000 people here tonight,” Cadd wisecracks, surveying the not-quite-capacity crowd. He hobbles around the keyboard, mimicking bad knees, before taking a slug of scotch and launching into his theme song from the 1973 sex-comedy Alvin Purple, followed by his country tear-jerker Let Go, a song that’s been covered by Gene Pitney, Glen Campbell and about three-score others over the past 45 years.

Down in the crowd, 50-something Gail Martin is groovin’ the moo with a friend who won’t give her full name because she took a sickie from her shift work to be here (“I would have earned public holiday rates, too — cost me 500 dollars”). An Oz rock diehard, Gail grew up on pub rock and has seen Daryl Braithwaite more times than she can remember. James Reyne, Russell Morris, she goes to see them all. But Brian Cadd? “I’ll tell you something, I bought a new car recently and I had to find one with a CD player because I’ve got his box set, and I have to be able to play it in the car. The CD player was a deal-breaker.” Ginger Man is the song Gail wants played at her funeral.

Onstage, Cadd is playing his Johnny Farnham hit Don’t You Know It’s Magic (an award winner at the 1972 Hoadley’s Battle of the Sounds) and then a new song about dying rock stars, Everybody’s Leaving. Then it’s time for the coup de grâce, the triple-whammy to end the show: A Little Ray of Sunshine, complete with inevitable acapella singalong, leads into Ginger Man, then Cadd hits a rolling Little Richard riff and launches into Your Mama Don’t Dance, the Loggins and Messina tune about how fusty oldies don’t like rock’n’roll, now transformed into a meta-ironic finale that gets this mature-age crowd upright and dancing on creaky knees and unstable lower-lumbar joints.

“That’s the best show I’ve ever been to, Brian,” one grey-haired female fan tells Cadd afterwards, as he sits signing CDs at a makeshift table outside the Spiegeltent. She hands over an original vinyl copy of 20 Dynamic Hits for him to sign and leans down to pose for a photo. “C’mon baby,” says Cadd cheerfully, wrapping an arm around her shoulders and smiling for the iPhone shot. Behind them, a queue of women-of-a-certain-age has started to almost jostle each other as they wait for their autograph moment. “Go right in, have a hug,” whispers one to her friend.

Gail Martin is here, getting another autographed Brian Cadd CD to play in her new car. Her friend looks a little giddy as she gets her selfie with Cadd. “We’re going to see Mondo Rock when they tour in August,” Gail confides.

Brian Cadd won’t be in Australia that month — he’ll be in the US, performing at the 50th Anniversary of the legendary 1969 Woodstock Festival. Appearing alongside him at that three-day event will be Santana, David Crosby, Melanie, Country Joe McDonald and... er, some guy called Jay-Z.

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout