Boris Becker on prison, bankruptcy and how new documentary proves he’s only human

The tennis icon blew all of his $140m fortune, declared bankruptcy and went to jail. After hitting rock bottom, the ball is back in his court.

If he wanted to, and he probably doesn’t, Boris Becker could tell the story of his life purely through the nicknames he’s been given. “Boom Boom” (improved by the German translation “Bum Bum”) came from his thunderous serve; “Der Bomber” and “Baron von Slam”, meanwhile, reflected his athleticism at the net – both of which helped him shock the sporting world by winning the Wimbledon men’s singles title at just 17 years old.

“The Lion of Leimen”, “the German god of light” and “the Rembrandt of tennis” were applied when he made the newspapers for all the right reasons, usually after one of his six grand slams. “Bonking Boris”, “Broom Cupboard Boris” and “Boris Debtor”, on the other hand, were applied when he made the newspapers for all the wrong ones, usually after one of his many, many grand logjams.

And for a while last year, Becker was known simply as prisoner A2923EV, serving at Her (and then His) Majesty’s Pleasure – initially at HMP Wandsworth in London, then at HMP Huntercombe in Oxfordshire – for 231 long days, after a jury in London had found him guilty of breaching bankruptcy rules. This was the worst of the nicknames.

“I was a number [inside],” he says, nodding slowly. “I wasn’t the famous tennis guy, that’s for sure…”

In a boxy double-breasted pinstripe suit and black turtleneck, Becker sits rigidly upright on a low sofa in a Berlin hotel suite, a free man, but looking only vaguely like the famous tennis guy. His hair (now a faded blend of grey and red) is cropped short, his voice croaky, and his manner – for decades marked by a sometimes problematic excess of energy, whether that was on the court, in the commentary box or in the back-of-house area of a west London sushi restaurant – ever so slightly chastened.

Occasionally he will lean forward into the Dictaphone, knees towards the floor, almost as if taking communion. “I’m good,” he confirms, “I feel recovered from my time inside.” He was released in mid-December and deported on a private jet to Germany, having served a fraction of his two-and-a-half-year sentence, but it was enough to cause him to lose more than 6kg.

It is his “big day”. In an hour, we will travel across Berlin for the world premiere of Boom Boom! The World vs Boris Becker, a two-part documentary for AppleTV+ about his spectacular rise and equally spectacular fall. It will be his first public event since his release from prison, and while the crowd will cheer and whoop, he doesn’t know that yet.

In some ways, he’s surprised to be here at all. “People like me, who went through so much, on a global scale, don’t make it past 50. So to still be here at 55, to be able to speak my truth with the help of a couple of people, is really important. Because I am a human being, I’m not just an image of a product or a name. There is an actual person behind the face.”

The doco is outstanding, as you might expect from Alex Gibney, the Oscar-winning director of Taxi to the Darkside, The Armstrong Lie and Citizen K, and John Battsek, Oscar-winning producer of Searching for Sugar Man and One Day in September. Gibney covers the whole story, from court to courtroom, interviewing his subject twice – first when he cuts a jocular, carefree figure in 2019, and then again, white-haired and noticeably more brittle, in early 2022, three days before sentencing. “When you’re as famous as I am for such a long time, there’s a lot of fake news, a lot of bullshit,” Becker says. “I’m not a complainer, I’m not a whiner, but sometimes you just have to make it stop.”

Numbers are less disputable, of course, such as the $50 million in career earnings that seemed to vanish after his retirement in 1999. He was declared bankrupt in 2017 with debts of $92 million before the law caught up with him for hiding $4.6 million worth of assets and loans to avoid paying his debtors.

With his partner, Lilian de Carvalho Monteiro, Becker arrived for sentencing at Southwark Crown Court in April 2022 wearing an All England Club tie. Two decades earlier, he’d been given a suspended sentence for tax evasion in Germany. This time, the judge cited that as an aggravating factor. “While I accept your humiliation as part of the proceedings, there has been no humility,” she said.

The moment his cell door locked at HMP Wandsworth was, Becker told a German broadcaster in December, the “loneliest moment” he’d ever experienced. “Not only the first day,” he says now. “It’s a proper punishment. Whoever says that prison life is easy is a liar. You have to deal with your own demons, especially in the first weeks. So you have to discipline yourself, discipline your mind, and discipline your time. If you don’t, it’s a very lonely place.”

Jail time was a possibility in the 2002 case, but he never thought it would happen. “Boris Becker behind bars? No way!” he wrote in his autobiography a year later. This time, he had an idea of what it might be like – “I watched those movies, I thought I knew prison life a little. But after a week, I realised I knew nothing about it. It has its own rules, its own difficulties. And you think it’s safe, because you’re in prison, right? But prison life is very dangerous. And that’s all I’m going to tell you about that.”

Fortunately he told the German broadcaster far more about that: at Huntercombe, a prison for foreign nationals, he had an “altercation” with a convicted murderer who threatened his life. “He tried to come after me, he told me all the things he’d do to me,” Becker said. He was saved when he shouted for help and a group of prisoners came to his rescue. According to Becker, the murderer had underestimated his popularity with the black prisoners. He later begged for forgiveness and kissed Becker’s hand.

In all, a humbling experience. “Humbling is one word for it. What it is, is your reality. You don’t have time to question whether it’s ‘humbling’ or not. It’s do or die, literally.”

There was plenty of support from the outside. He told Lilian, the 32-year-old daughter of the former defence minister of Sâo Tomé and Príncipe, an island country of Central Africa, that he would understand if she left him, but she remained. “Thankfully I have this incredible partner. Through thick and thin she was really there all the time.” She visited as often as possible, as did his sons, 29-year-old Noah and 23-year-old Elias, from his first marriage. But he decided that Anna, his 22-year-old daughter from the infamous three-minute encounter in the London sushi restaurant Nobu with Russian model Angela Ermakova, and Amadeus, his 13-year-old with his second wife, Lilly, ought to stay away.

There were letters, too. “True. I received a lot of fan mail, daily. But not every prison warden liked the fact he had to carry another 20 letters to my cell – ‘You again, with your 25 letters! Who do you think you are?’ Most of them were positive. Very stimulating, very supportive. The longer the letter, the slower I read, because then another hour’s gone.”

At Huntercombe he had a job helping the head of the gym, who happened to also teach Stoicism. “One of the things you must learn inside, and quickly, is acceptance. You have to accept your verdict, accept your time, accept where you are. The only thing you can be the master of is your mind. I managed. I think my tennis life helped. I was probably a Stoic when I was playing, without knowing it.”

-

“Am I good when the going gets tough? I’m probably better than most. That’s the problem”

-

The two parts of Boom Boom! The World vs Boris Becker are titled Triumph and Disaster, a reference to the Rudyard Kipling line – “If you can meet Triumph and Disaster. And treat those two imposters just the same” – engraved above the players’ entrance to Wimbledon Centre Court.

For better or worse, Becker really has always treated those two the same, which is why Gibney and Battsek found him so compelling. Many of Becker’s rivals, heroes and mentees, including Björn Borg, John McEnroe and Novak Djokovic, show up as talking heads. But Becker, of course, is the star. “Most athletes are utterly boring talking about their sport,” Gibney says, “but Boris is a great storyteller.“ And he has a great story to tell. “The guy won six grand slams, an Olympic gold, coached Novak Djokovic, won Wimbledon at 17 – which, by the way, is easy to roll off the tongue, but to win Wimbledon aged 17, at your first attempt? That’s unbelievable. This was a man who was deeply flawed, yes, but he hadn’t really been acknowledged for what he’d achieved.”

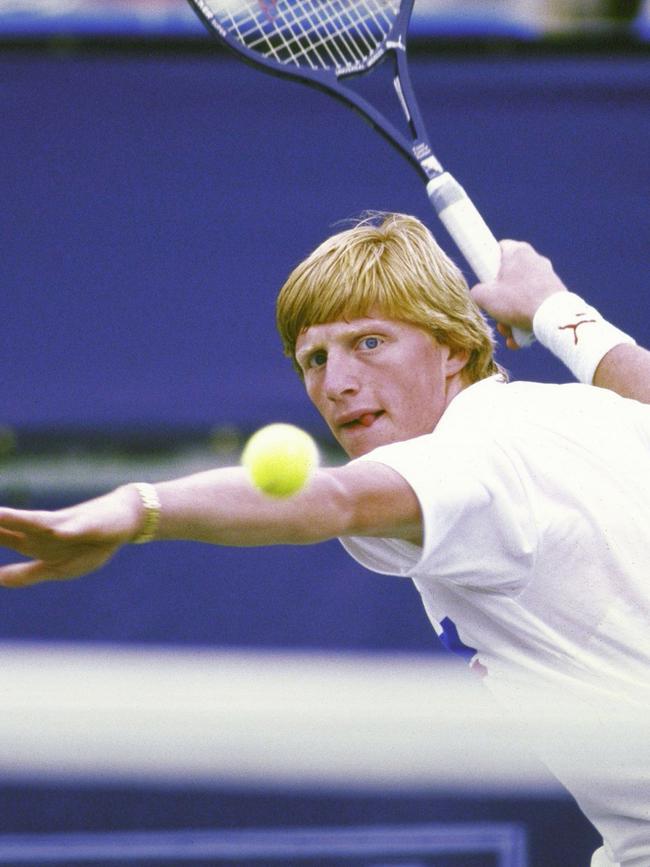

Boris Becker has felt like a brand, or at least public property, ever since July 7, 1985, the day he appeared on Centre Court – all tight shorts, strawberry blond mop and boyish energy – to beat Kevin Curren in four sets.

Becker and his older sister were raised in a middle-class, Catholic household in Leimen, then West Germany. He started playing competitive tennis at the age of eight, and would train with a young girl from the next town called Steffi Graf. They would go on to become the two greatest German players of all time.

Sponsors, journalists and female fans threw themselves at him. Becker gladly caught them all. “All of a sudden you’re the boss. The CEO, CFO and COO of a company called Boris Becker Inc that makes millions of dollars a year. So as an 18-, 25- or 32-year-old tennis player and not a businessman, you have to make business decisions, which is bound to lead to mistakes,” Becker says.\

Nor did becoming the world’s most famous German sit well in his homeland. The relationship was always uneasy, especially as Becker, forever his own man, wouldn’t play along with the media image of him as a symbol of a revived fatherland. After the Berlin Wall came down he refused to be an ambassador for Berlin’s 2000 Olympic bid, believing it was too soon for a return to nationalism. The media scrutiny was poisonous when he married Barbara Feltus, a black German-American model, in 1993.

“From early on, I didn’t do things the Germans wanted me to do,” he sighs. “I was political, I was outspoken, I married a black woman, I have mixed-race kids, I spoke about racism in the ’90s, when there was no such thing as Black Lives Matter. I did nude photographs with my wife, when we really showed the Germans how racist they were in the ’90s.”

He currently has no fixed abode, having spent the past two months shuttling around Europe, but it sounds as if Germany is off the cards. “I am proud to be German, born and raised, but I could never live [here]. They wouldn’t give me the space, and the privacy that even Boris Becker has the right to.”

Gibney presents a theory in his films: that on court, at least, Becker was at his best when he fell behind, and knew it, creating imperilled situations purely so he could escape them. “He almost played a trick on himself,” Gibney says. “It was hugely helpful to him as a player, but maybe not so helpful to him… later.” It’s what makes a moment towards the end of the second film, when Becker breaks down, announcing he has hit rock bottom, quite so powerful. The escapologist met his match.

“Look,” Becker says, bristling a little, “Am I good when the going gets tough? I’m probably better than most. That’s the problem. What sets you apart, is it your serve? Your footwork? Your fitness? Or is it the ability to play under pressure? Mine was the ability to play best under pressure. That’s what he meant, I become my strongest when I’m in most difficulty. Is that by choice? No. I’d like to have an easy life, like anybody else. Is it in my DNA? Probably, otherwise I’d have done things differently. But everybody has their habits.”

Becker and Barbara divorced in 2001, two years after his retirement from tennis, and weeks after he cheated on her with Ermakova in a stairwell at Nobu. (He has repeatedly insisted it was not a broom cupboard, as widely reported). At the time, Barbara, heavily pregnant with Elias, was in hospital with contractions. When Ermakova broke the news of Anna’s impending arrival, Becker denied paternity. A DNA test, not to mention Anna’s uncanny resemblance, proved otherwise.

To everybody’s credit, the kids are more than all right. Noah, an artist who arrives with Lilian at the premiere later, lives in Berlin. Elias studies film at NYU. Anna has just finished a BA in modern art and is spending her “gap moment” doing the German version of Strictly Come Dancing. And Amadeus is at school in London. Becker is unable to take the risk of visiting Britain until his licence runs out next year.

The logistics of keeping up with what he calls his “patchwork family” haven’t always been easy. Today he is on great terms with Barbara, and good terms with Angela. And Lilly… well, on the morning we meet, the papers are full of Lilly calling him “a devil” who thinks “the world revolves around him”. So let’s call Lilly a work in progress.

We are still no closer to determining exactly how Boris Becker ended up in prison, but suffice to say that when his lawyer explained in 2017 that “he is not a sophisticated individual when it comes to finances”, it was a good example of legal understatement. Divorce, child support payments, the $10.5 million settlement over his German tax case, questionable business ventures, a generous and sybaritic lifestyle… it all added up, or rather, subtracted down. Debts mounted, payments were missed. He took an emergency loan from the British billionaire John Caldwell, then failed to pay it back within three months.

A one-time professional poker player, Becker is fond of the old saying, “No shame in folding.” In 2017, to the amazement of the public in Britain – where he was adored as a BBC pundit and, until the mid-noughties, our pre-eminent hyper-horny, financially haywire, wild-haired Boris – Becker had to declare bankruptcy. “In hindsight you’re always smarter,” Becker says today.

He is trying to move on, trying not to feel bitter, even if he does keep returning to the idea that he was badly advised, and does tweet about British MP Nadhim Zahawi’s tax affairs, and did recently imply that he would have been treated differently if he was named “Peter Smith”, or his jurors were older.

Sponsors have stuck by him, and the commentary work for Eurosport has restarted (so have discussions with the BBC, he says). The entrepreneurial spirit is alive, too. He has “plans”, and while he won’t say what, in 2021 Lilian registered a company called BFB Enterprises, which happen to be her partner’s initials.

Bounceback Boris has always enjoyed resurrection. “Here I am. At the end and the beginning at the same time. Back in the qualifying rounds … And the tournament is called life,” he wrote in his autobiography, in 2003.

The tournament of life, I repeat. How’s that going? “We are in the middle of it,” he says, perkily. “My greatest achievement, I think, is that after all the trials and tribulations and hardships, I’m still alive and well... I’m still here to tell you my story.” A firm nod. “I’ll continue to play the tournament of life for as long as I live. The ending is still very open.”

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout