Bob Hawke and Blanche d’Alpuget: love, legacy and a secret brush with death

Blanche d’Alpuget has known two Bob Hawkes in her lifetime. There was Mr 75 Per Cent who she’d meet in secret hotel rooms. And there’s the devoted grandfather doing his crossword.

Here comes his only weakness, the woman he’d die for and the woman who kept him alive when he was halfway dead. Her name sounds better when it’s whispered. D’Alpuget. It’s French for “deadly blonde from Darlinghurst”. Trouble with a capital “B”. The sum of a thousand night-sweats and old muscle-memorised paranoia that once told the most popular Australian prime minister who ever lived that around her this great political slugger would always be punching above his weight.

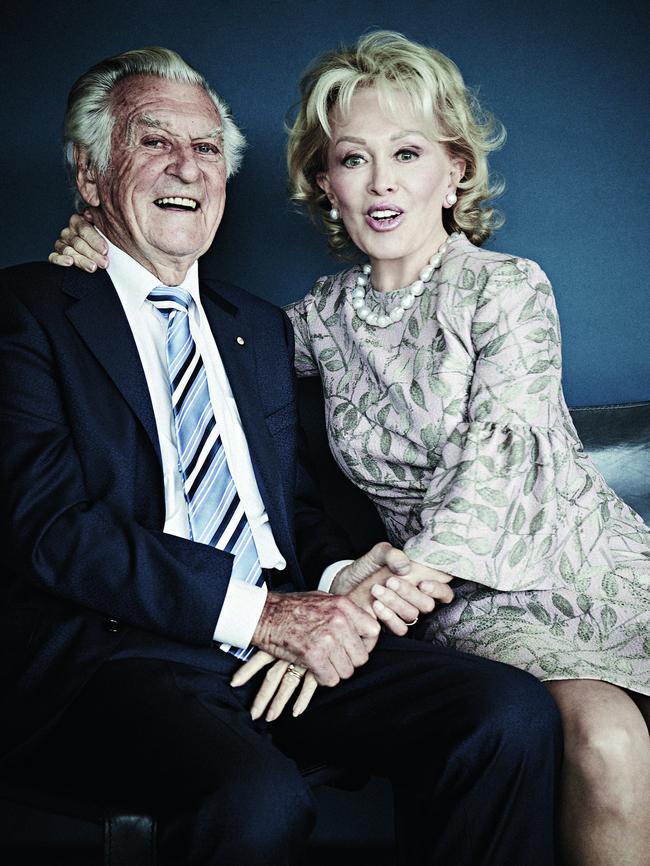

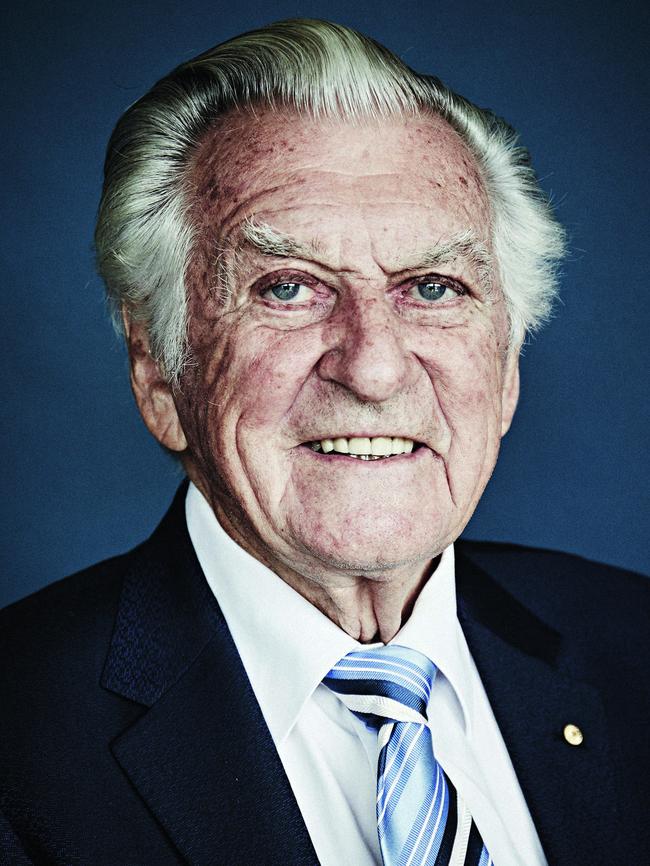

“Here she is,” Bob Hawke announces, in case anyone missed the lightning strike of his 73-year-old wife, Blanche, zigging and zagging down an internal staircase from her upstairs bedroom. His old bird-of-prey eyes catch fire and he says what people say when they see Uluru for the first time or when they lean their heads into the Grand Canyon. “Ha!” he says and it sounds like a brag.

A four-level concrete block home with a putting-green rooftop built into harbourside north Sydney bushland, where a funicular cliff railway takes residents down to deep blue-green Sailors Bay and its endless supply of fat silver bream. A half-tonne sculpture of an African woman’s head in the entry foyer. Grand oil paintings on the walls of the second-floor living room. Horseracing scenes for the famed Oxford Rhodes Scholar who studied as many form guides as he did economics textbooks. A vertical fish tank built into the wall. A sculpture by the white sliding doors to the terrace where Bob does his crosswords and Sudokus most days over a fat cigar. The sculpture, Whatever, is by Blanche’s son Louis Pratt, a gifted artist who has lived here with his mum and stepdad since 2009. Whatever shows a young man in a hooded jacket, hands in pockets, leaning back so hard he’s creating an illusion of uneasy balance, some tribute to the cult of meh or misspent youth or maybe what happened to all those Australian children who were still living in poverty by 1990.

Bob shuffles slowly to his wife — he suffers from peripheral neuropathy, which causes nerve pain in his feet — and plants a smooch on her lips like he hasn’t seen her in a decade and not, in fact, since breakfast.

He turns 88 next month. One floor below us is the games room where he celebrated his 70th birthday in 1999. Great band that night, great food, too, and two ice statues of a naked man and woman, endless wine funnelling out of the iced gentleman’s penis and the lady’s breasts. One esteemed guest drew cheers when she forewent the standard wine glass in favour of slurping her fill direct from the ice man’s unorthodox faucet. Then John Singleton turned up to gift the birthday boy with a quarter-share in a racehorse named Belle du Jour, which would go on to win the 2000 Golden Slipper. Things happen like that in Bob’s world, always have. The games room’s walls are lined with framed sporting photographs and shots from ’83 to ’91, the glorious full-tilt, fifth-gear PM years: a signed picture from Neil Armstrong; Bob and Alan Bond in post-Australia II jubilation; Bob copping that cricket ball bouncer in the right eye in 1984, the worst year of his life, the year against which all joy is to be measured.

We’ll start at the end and work our way backwards today. We’ll start at death and end at rebirth. The untold story of the near death of Bob Hawke and how he was born again.

But first he will murder a Cuban. He sits at the end of a long oval-shaped polished wood table that could easily host 16 or so people for dinner. He wears a fine navy blue suit that shimmers when you get close to it. Black suede derby shoes on his feet. He’s fanging for a cigar but Blanche won’t let him smoke inside today because she can’t stand the smell. A cigar might make all this maudlin talk of death come out easier.

“Yeah, I was very crook,” Bob says, his voice low and measured and confessional. He shakes his head. “I was very sick. I picked up this awful thing in the Middle East and …” He dwells on something for a moment, takes a long breath. “… they tell me I could have been on the way.”

Bob nods at his wife, sitting across the table. “She was absolutely fantastic,” he says. She saved him, he says. The love of a good woman can do that for a bloke. Blanche shrugs her shoulders, suggesting bedside vigil-keeping was part of the deal back in 1995 when she said “I do” to the recently divorced former PM and Australia’s tabloid magazine industry spontaneously combusted.

Bob rises slowly from the table. “You OK darling?” Blanche says. He nods, creeps like a seasoned cat burglar toward the harbourside terrace where his cigars and matches sit on an outdoor table. “I’m just gonna be out here for a bit,” he says. Blanche nods, her eyes following her husband all the way outside to his smoking chair.

“A friend of mine says my Enneagram number is eight,” she says. “We’re very protective.” Blanche is the spiritual type and Bob is not. Spiritual types like Blanche talk about the Enneagram of Personality that splits the human psyche into nine interconnected personality types — number “eight” types are said to value truth, fear being controlled and violated, have a passion for lust and an “ego fixation” for vengeance.

Everybody still wants a piece of Robert J. Hawke . Youth skateboarding brands want to place his image on their T-shirts. Festivals want him as a headliner. Thousands will again squeeze into a tent at the Woodford Folk Festival next month to hear him discuss whatever is in his big sprawling eucalyptus-tree mind — China relations, turning Australia into a nuclear waste dump, his beloved Landcare — while some hip young rock act on the festival bill will play to 70 people and wonder why everybody’s flocking to the silver-haired yarn spinner in the speaker’s tent, begging him to autograph their Medicare cards. Beer brands such as “Hawke’s Lager” piggyback on the larrikin yard-glass-slamming everyman lovability that saw him capture the highest approval rating for any Australian PM in history: 75 per cent in November 1984, the worst year of his life, the year against which all joy is to be measured.

Blanche doesn’t want a piece of Bob. She wants all of him, whole and content and alive. “He was just so close to death,” she says softly. “It was awful.” Tears in her grey-green eyes, but not tears of sorrow. She runs a pinky finger along her right eye, smudging her black eyeliner.

It’s not easy keeping secrets for Bob Hawke. She kept her share during the most talked-about love affair in Australian political history that stretched all the way back to a modest Canberra motel room in 1978 when the 49-year-old ACTU president, husband to Hazel Hawke, asked 34-year-old journalist and author Blanche to leave her diplomat husband Tony Pratt and spend eternity in his wiry bronze arms.

She doesn’t know why she kept his brush with death in mid-2015 a secret. It’s easier that way, maybe. Less complicated. Blanche whispers what it felt like to be by Bob’s bedside in Sydney’s St Vincent’s Hospital. She figures he was three weeks from death, wilting, dissolving in his bed as a cocktail of super-antibiotics played a roulette game of survival inside his body, fighting a stomach bug that got so severe it left him with a paralysed intestine. “I went and bought our graves,” Blanche says. “I did it without asking him. I went with a friend who was advising a cemetery, a new cemetery, and I said, ‘I think it’s time I bought our graves’. ”

She breathes deep. “They’re difficult decisions,” she says. “Then telling the children. Telling them so they weren’t terrified while also not letting the press know or any of the news media. That was really difficult and … umm … I was just sort of eyeballing the nurses and so forth, just saying it without saying it, you know.” This is not to leave the hospital room.

Blanche looks out to the balcony. Bob strikes a match to light his cigar. “I remember we were fishing once, this was in the early 2000s,” she says. “He hooked a shark. It was a very big and slothful shark up in Queensland and he fought that bloody thing for three hours. Three hours! It was unbelievable. He would have been 72 or 73 and he just would not give up. That’s him. He won’t give up.”

Like most games of chance Bob Hawke indulges in, he got lucky in 2015. He came good, though he faced a year of medical appointments and regular doses of the intravenous antibiotic Vancomycin to ward off life-threatening infection. He was typically stoic throughout but Blanche was forced to confront notions of a life without Bob Hawke in it.

“Yes,” she says. “Yes I did. It was soon after that that I put a deposit on an apartment in the city.” She slaps the table three times. “Boom, boom, boom.”

She does that a lot when she needs to be matter-of-fact in the face of fate. Slaps the table and says “boom”. Political giants are challenged by their treasurers. Boom. Marriages fail. Boom. Lovers meet again. Boom. Lovers die. Boom. Lovers rest side-by-side for eternity. Boom. Boom. Boom.

“The graves are side-by-side,” she says. “We chose a spot where the public can come. It’ll be nice. It’s in a rose garden and there’s a seat there so if a member of the public wants to come and have a sit, they can.”

She looks outside to the terrace. Bob blowing a cumulonimbus of cigar smoke that hangs for a moment above the right shoulder of his blue suit. “I think we’ll go on,” she says of life without him. And it’s hard to tell if she means herself and their respective children and grandchildren or the greater population of Australia. More tears now but not tears of sorrow. She wipes her grey-green eyes again. “I’m sorry,” she says. “My eyes are watering because I’m very allergic to eye make-up.”

“Trump,” says the photographer in Bob and Blanche’s living room. “Turnbull,” says Bob. Click.

“Melania,” says the photographer, playing a game of rapid word association with the former prime minister to loosen his smile for a quick portrait. “Rudd,” Bob says reflexively, bouncing in his chair like he did all those years ago when he said that perfect line, “Any boss who sacks anyone for not turning up today is a bum.” Click.

Blanche enters the frame. Studies his face. The protector. The eight. “Does he need any powder?” she asks a make-up artist.

Bob realises she means make-up for his face. “C’mon,” he winks. “It’s very important we get back to cigars.” Blanche shakes her head.

“He’s known for being impatient,” she says.

Bob gazes at Blanche. “It’s from all the time I’ve spent waiting for you,” he says.

He says that with such charm that it comes off like an ode to true love’s enduring nature. His old eyes twinkle and you remember that even Tamie Fraser, the wife of his old political rival, Malcolm, called him sexy. Maybe all those whispers about the Queen having the hots for him were true? “Ha!” Bob laughs knowingly. “We always had a good relationship from the start. I loved the Commonwealth and she absolutely loved the Commonwealth.”

“There is no doubt, the Queen likes men,” Blanche says, cryptically. “You could tell she was enjoying his company.”

Blanche takes a seat beside her husband before the camera. “Can you shift ya bum?” she says, trying to get comfortable in her seat. Click. “How you feeling, Blanche?” asks the photographer.

She wraps an arm around Bob, leans her head into his shoulder. “I’m feeling love!” she announces brightly. Then she slips a right hand dangerously towards the great prime minister’s crotch. “He’ll feel it too in a minute!” she howls. Click.

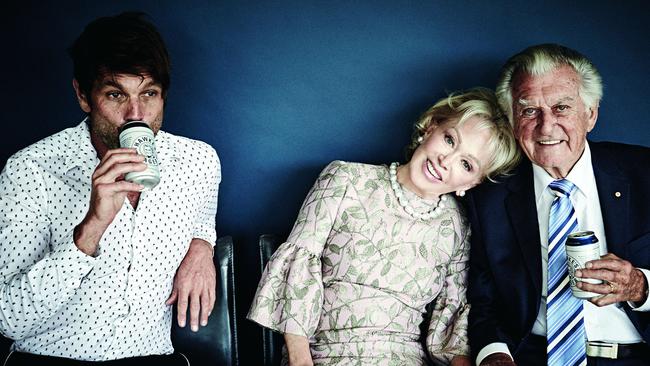

A third person enters the frame. “Look at the madsurfie,” Blanche says. “He’ll make a very nice handbag with that skin one of these days.”

Almost a year ago, journalist and author Derek Rielly pitched an idea to his book publishers. What if Rielly spent a year catching up with Bob Hawke on a series of Wednesday afternoons? Something like Tuesdays With Morrie meets The Hawke Memoirs. Bob could simply smoke cigars on the balcony and reflect on a set subject each afternoon — love, sex, death, religion, politics, Trump, Turnbull, Keating and so on. Rielly could simply write what he heard, write what he saw.

The published result, Wednesdays With Bob — co-authored by Hawke and Rielly — reads the way a long and languid balcony cigar with Bob Hawke feels, filled with moments of blinding illumination, bruising and melancholic human drama — including that brush with death in mid-2015 — and occasional blunt Hawke hilarity. Bob’s poem about his challenges with ageing male urine dribble is worth the cover price alone. Rielly’s knockabout tanned Bondi surfer bloke physicality belies a sharp political mind and a knowledge of Hawke-era Australia to rival that of the Silver Bodgie’s original biographer, Blanche.

“Derek has far exceeded my expectations,” she says. “When I first met him he was wearing such a low-slung, tight pair of jeans that he had his bum crack showing and I thought, ‘What?’ I said to him, ‘Your jeans are too revealing’. And he said, ‘They’re very fashionable’. And I thought, ‘Oh great, a fashion victim as well’. ”

“I feel like the thing Bob Hawke gave us was a sense of pride in our country,” Rielly says. “It didn’t matter who you were, whether or not you were a tradie or a banker, it felt like Hawkey was there for you. He was winning elections at a time when people were losing their homes, losing their businesses, but we trusted him. Bob Hawke made you proud to be an Australian. I just wanted to lasso that history.”

Rielly had some heavy hitters weighing in on the Hawke legacy. The book features interviews with Kim Beazley, John Singleton, Gareth Evans (“We were in the presence of someone who a lot of people perceived as God”) and John Howard (“Yeah, well, I didn’t share those views [but] Hawke is the best Labor prime minister Australia’s had”).

Bob’s former chief economic adviser, Ross Garnaut, raises a conversation he had with Bob long ago where they both concluded that the Hawke era’s great failure, the 1991 “recession we had to have”, was most assuredly avoidable. “We made a mistake there,” Bob admits today. “You had the crash on Wall Street. We underestimated the resilience of the market. We had to keep interest rates down and then we had to put ’em up and we left it too late and we had to put them up too high and caused a lot of the problems. It was a mistake we made.”

In the book, Garnaut links the poor reading of the economic horizon to the famed breakdown in Hawke’s relationship with his treasurer, Paul Keating. Bob sucks on his cigar contemplating this, exhaling slowly. “I don’t think so,” he says, flatly. He says he has great affection for Keating but he hates that he’s a hater. “In the history of federal politics he was outstanding,” Bob says in the book. “He did so many good things that it’s a real pity he … two things. One, that he’s such a hater. He just hates! And he just wants to claim a bit more than he’s entitled to.”

I ask Bob if he would consider — before he ventures off to that spot in the rose garden Blanche has bought for him — having a lengthy sit down with Keating to settle, once and for all, who is entitled to claim what in their shared and incendiary legacy. He sucks on his cigar again.

“No,” he says, flatly. “But if there’s anything that I could ever do to help him with that terrible tinnitus that affects him, nothing would make me happier.” He thinks for a moment more. “I was extraordinarily lucky,” he says. There’s not a single person in modern government that he would substitute any member of his 1980s cabinet for. “I had this cabinet which is recognised as the best since Federation,” he says. He says he can’t think of a single outstanding democratic leader anywhere in the world today. “It’s one of the funniest things I’ve found about politicians,” he says. “They represent people but so many of them are so very coy about meeting them; but that was something I enjoyed and people realised that.”

He believes Malcolm Turnbull is crippled by an inner turmoil. “He’s ashamed of himself for what he’s done in terms of compromising his beliefs to get the numbers against Abbott,” he says in the book. “And if you’re ashamed of yourself that’s not a very good basis for leadership.” Shame. Guilt. Inner turmoil. Concepts not unfamiliar to Bob.

“Where’s that milkshake gone?” he says, as the photographers and make-up artists pack up their gear, photoshoot done. Bob’s on the milkshakes again. Ice-cold strawberry milkshakes vacuumed through a straw. He says he has a drinker’s throat. Something physiological in it. His throat just opens up and beverages slam down it, always have.

When he was eight years old his mother, Ellie — and all emotional roads in the Bob Hawke story eventually lead back to his beloved and deeply influential parents, Ellie and Clem — made him promise he wouldn’t touch booze. But in the early phases of their clandestine affair — the ACTU phase — Blanche remembers Bob as an alcoholic; a “self-hating” drinker. John Singleton says walking around Sydney with Bob in those days was like walking around with a Beatle. But Blanche always got Bob in the late hours when the rock star charm had worn off, when boozy paranoia had consumed his peerless dinnertime wit. “I did see a lot of the dark side of him,” she says. “I’m sure there was a great deal of guilt because he promised his mother he wouldn’t drink. Boooom.” She slaps the table she’s sitting at. Full stop. Case closed.

“But, look, he wasn’t drinking at all [during his leadership],” she says. “Anybody who says otherwise is misinformed or lying. He did not touch a drop for 13 years. I knew if he was ever going to achieve his ambition he would absolutely have to give up drinking.”

How he managed to do that, she says, is related to that slothful shark he spent three hours reeling in, aged 72. I raise the notion of inner turmoil and leadership. If Turnbull’s leadership has been affected by the secret shame of compromise, surely Bob’s was affected by the secret shame of infidelity?

“I don’t think Bob ever suffered much guilt over his sexuality,” Blanche says. “I really don’t, because I think he was clear-thinking enough to know that the system is crooked. The monogamy system is crooked.” She laughs to herself, knowing full well she’s stirring a moral pot she unashamedly tipped over in the 1990s. “Crooked for a natural human life,” she emphasises. “It causes so much misery and conflict and violence and stress to children and on and on and on. To what degree Bob thought that through, I don’t know, but I think he recognised that he was living in a crooked system, so don’t bend down to it.”

She loves this man sitting opposite her so fiercely there was a time, she says, when he drove her to the edge of suicide. “Oh yes,” she says. “Oh yes. It was the love. And hatred.”

It was a brief bout of deep despair in the late 1970s when Bob had stopped phoning her, refocusing his attentions on his marriage at the beginning of a new road to becoming PM. The “eight’s” despair turned quickly to vengeance, saw her dreaming up ways of killing her lover, embracing him passionately then stabbing him in the ribs, drawing the blade up to his heart.

“I went through that dark night of the soul when we broke up,” she says. “And I came out the other side. I got over it. And then I really flung myself into writing, which is one of the great curative and healing processes.”

I ask Bob if he understands that level of despair, the kind that leads to ending it all. “I understand that,” he says. “I understand completely. I had some moments of despair.”

The story of Blanche’s sexuality begins in a dark place. She was 12 years old when a neighbour in his 50s, a judge, began kissing her. “Oh, the judge,” Bob laughs, shaking his head. “Dirty old bastard.”

The kissing turned into a confusing and formative love affair. “I honestly think that he was impotent,” she says. “And I really wonder how often it is when men of that age are grooming and molesting younger women, is it an attempt to overcome their impotence? They think, ‘Oh, if only I was younger and I had this younger flesh, it will give me back that strength that I’ve lost’. I’ve never heard of anybody writing about that.” Bob chuckles nervously, marvelling at one of the few people in the world who could turn a potentially traumatic encounter with a paedophile into a potential thesis. “But it’s such a politically incorrect subject, that there might be some iota of compassion or understanding for them,” she says. “Though [paedophiles] are very selfish people and he was a very selfish bastard. A bad bastard. He was also seducing his housekeeper’s son. That was the thing that did it for me.” Bob shakes his head in disgust.

One pivotal moment in the story of Bob and Blanche is the dream he had in 1978 the night before he first asked Blanche to marry him. The details are sketchy but the dream involved some kind of metaphorical or symbolic spinning roulette wheel and a ball that landed on Blanche d’Alpuget.

“I went and asked a psychiatrist, who’s a buddy,” Blanche clarifies. “I’ve never been to a psychiatrist, though maybe I should have. But I said, ‘What does it mean?’ And he laughed and he said, ‘Well, it means he thinks marriage is a gamble’. ” She howls with a laughter that echoes across Sydney’s North Shore. “Wow, of course, Bob loves gambling and …” She thinks for a moment. “…it was a risk for Bob.”

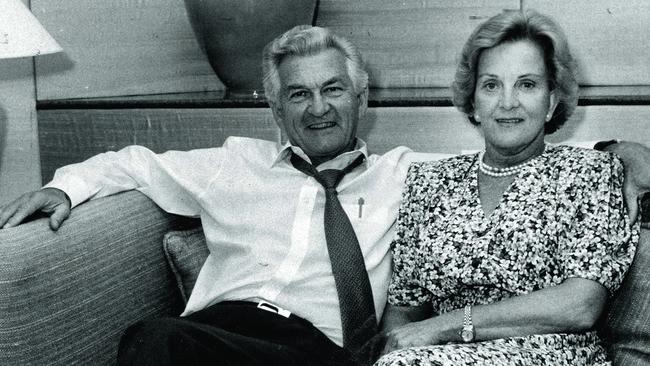

He was supposed to work through his marriage to Hazel. He was supposed to swallow his feelings, drink and work through them, bottle them up and let them explode on hot drunk summer nights like all those other Aussie battlers out there who believed, heart and soul, in the sanctity of marriage — even a loveless one. Blanche calls Bob and Hazel’s divorce a “win-win-win”. Hazel was liberated from an “ugly, dead” marriage, freed from the suffocating shadow of Mr 75 Per Cent.

“Each of us asked the other to leave,” Hazel once reflected on the marriage. “We both stayed.” In 2014, Bob’s grandson David Dillon told Australian Story the divorce “tore our family apart” before old family wounds were healed in the wake of Hazel’s 2013 death after a long battle with Alzheimer’s.

“It took an enormous amount of courage on Bob’s part,” Blanche says. “It took much more courage on his part than on mine. Because I was a single woman, divorced. But he was married. The whole country expected him to behave in this way and was unaware of what his true feelings were and so were bound to be shocked, angered and amazed when they discovered them. And they were [angered] and they expressed it, and still do, unfortunately.”

Do they receive public abuse even after all these years? “Nooooo, noooo,” she says. “People are not that courageous.” Bob smiles wide, his eyes suggesting he’d dare someone to try. They call their love a spätlese, a German wine term meaning “late harvest”. “You know, a late pick,” Blanche says. “Like good wine,” Bob starts to say, and Blanche finishes his sentence. “It gets sweeter. And I think that comes from within both of us. A greater maturity from overcoming, I hope, your flaws and hang-ups and silliness and that tends to fall away with age, if you’re lucky.”

“I’m happier than I’ve ever been,” Bob says.

And that happiness was hard-won. That happiness, even today, is measured against 1984, when he fell into what he figures was a six-week depressive episode in the year of an eight-week election campaign clouded by public revelations that his youngest daughter, Rosslyn, was a heroin addict. He pushed himself dangerously close to emotional and physical breakdown, barely able to concentrate through persistent agony caused by that famous bouncing cricket ball that drove glass from his smashed spectacles into his right eye.

The memory of it makes him wince in his chair. “I just can’t explain the pain I was in,” he says. “The physical pain I was in after the eye. I just went through that debate with [Liberal leader Andrew] Peacock and the whole campaign and I was just in agony, physical agony, the whole time. And mixed up with that, the emotional agony.” He shakes his head but doesn’t shy from the truth of it. “The emotional agony of feeling I’d failed as a parent.”

“I still get a great sadness,” Blanche says. “A great sadness because it was torture. He was being tortured.” Bob nods silently. “Yeah,” he says. And it’s time for another cigar.

Blanche d’Alpuget has known two Bob Hawkes in her lifetime. There was Mr 75 Per Cent who she’d meet in secret hotel rooms, the fifth Beatle with his charisma and his confidence and his rare common touch. And there’s the Bob she sees now on the balcony, the tender, vulnerable, wise and devoted grandfather doing his crossword. She doesn’t know exactly when one became the other. “It doesn’t happen immediately,” she says. “It happens over a period of years.” But she thinks maybe the new Bob was born in that brutal 1984.

“Birth is painful,” she says. “So if you’re coming to a new birth within yourself, it’s going to be bloody painful. And many people shy away from that. And they will find ways of avoiding it, but if you go through it, you’re a new human being.”

When she looks at her husband today she sees no darkness in him, only light. “Yeah,” she says. “He has additional photons. He has a little extra light.”

And the face of the silver-haired ex-PM does indeed brighten because he’s jagged an answer in his afternoon crossword, a few more elementary particles of this old and new Bob Hawke, aged for 87 years and 11 months, exploding into light. Boom. Boom. Boom.

Wednesdays with Bob, by Bob Hawke and Derek Rielly (Macmillan Australia, $29.99) is out November 28

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout