Beyond belief: the cleaner, her 92-year-old boss and a baffling murder

Marjorie Welsh wasn’t easy to kill. Bleeding profusely, in the midst of her pain she felt another sensation: bewilderment. Because the woman silently savaging her was no stranger.

Marjorie Welsh wasn’t easy to kill, even if her physical demeanour suggested otherwise. She was 92, she had a pacemaker, a corneal implant and a hip replacement. A creative, social woman who lived alone, she used hearing aids and even with the help of the walking canes she had crafted for herself, she was slowing. Nothing about her bearing suggested she could survive the assault that began in her tidy kitchen on an otherwise unremarkable summer morning three years ago.

Like most days, she started this one feeding the birds in her garden. When she stepped back inside her cottage in Sydney’s inner west on January 2, 2019, into a bright space filled with decades of her handiwork, she was invigorated but hardly vigorous, and offered no defence as an intruder began thrashing her with the canes she had lovingly made. Mostly she just cowered on her kitchen floor, trying to protect her face.

Somehow, as she was bashed with a variety of her possessions and repeatedly stabbed, she kept breathing. Bleeding profusely, in the midst of her pain she experienced another sensation: bewilderment. Because the woman silently savaging her was no stranger. She had been welcomed into Welsh’s home regularly, with great affection, and even, just recently, with a gift for her child.

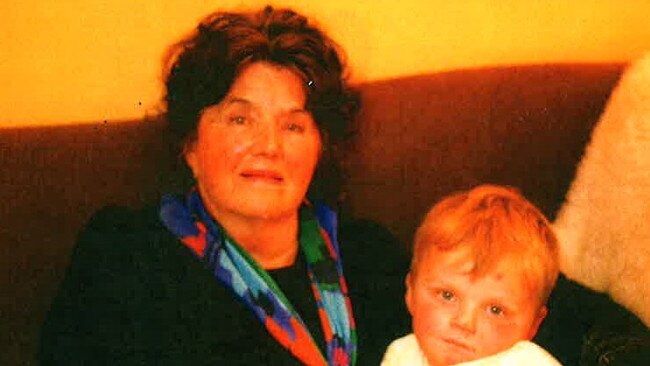

Hanny Papanicolaou was Welsh’s cleaner. Despite their vastly different backgrounds and the almost 60 years that separated them, the pair had bonded during their weekly encounters. “She has always been charming,” Welsh, miraculously still alive, told police hours after the assault that would ultimately be fatal. “I thought that we were friends.” Her sentiments were reciprocated. “She is like a mother to me,” Papanicolaou would later declare.

The identity of Marjorie Welsh’s killer was no mystery. Even before going in for emergency surgery she identified her assailant to police as “the housekeeper… Hanny”. The question was not who ended her life, but why.

Before it became a crime scene, Welsh’s home was a tableau of domesticity. The renovated kitchen, orderly and neat, with a shiny toaster on the bench and bottles of oil lined up beside the stove. A crocheted cloth on the polished wooden dining table. The bed dressed with white sheets, corners tucked just so.

“It was my dream world, I had made it,” Welsh would later remark of her home, which was filled with so many objects she had created over a lifetime – silver chains, beautifully woven baskets, a brightly striped rug. For decades she had lived on a small farm at Box Hill, on Sydney’s north-west fringe, and would proudly clean her home in anticipation of either of her two daughters visiting. But after her husband Jim’s death in 2014, she wanted to be closer to her family. Selling her 2ha property with its modest home for $8 million, she would be comfortable for the rest of her days.

That she could then move to a cottage in the inner-west suburb of Ashbury, where she also allowed herself to hire a weekly cleaner, was, for Welsh, “the icing on the cake”. With its modernised interior and a Hills Hoist in the side garden, her new home from mid-2018 was just around the corner from one of her daughters. This enabled Liz Welsh, a barrister, to see her mother frequently, as she did on the last night of 2018 when she noticed that she was moving more slowly than usual.

Although Marjorie Welsh was ageing she remained sharp and social, often enjoying dinners out, and she had just been cleared by her doctor to travel to Japan. In her 10th decade she was determinedly independent, dusting her mix of old and new furniture between weekly cleans, washing and ironing her clothes, and pottering in her garden – which, as another year dawned, was bursting with life.

On the second day of 2019, when much of the city seemed to have settled in for an extended post-Christmas siesta, Welsh prepared for a morning at home. On this Wednesday she dressed in a dark grey skirt and a green floral blouse, set her hair with rollers and donned a hair net.

Until recently, Wednesdays had been a fixture in her calendar. Liz Welsh had arranged for her long-term cleaner to attend her mother’s house every week on that day and Marjorie had warmed to Hanny Papanicolaou, a 30-something mother of two who had arrived from Indonesia 12 years earlier. She was an efficient worker and good company, and as she swept the back patio each week – most recently on Fridays – the two women often chatted. Papanicolaou worked for multiple households but it was with Welsh that she developed an attachment. “She is such a beautiful lady,’’ she would later declare. “She is always waiting for me, asking ‘How are you?’, opening the door for me… when I go home she is always hugging me.”

Welsh had shown great interest in Papanicolaou’s family; they had exchanged Christmas gifts and the cleaner had taken her youngest child to visit Welsh, who gave her a gift of $50. Papanicolaou recalled Welsh hugging the child. “I was taking pictures,” Papanicolaou would reveal. “She was teaching me how to raise the kids.”

While Welsh ambled through her garden on that morning of January 2, 9km away at her townhouse in Roselands Papanicolaou woke feeling tired. She had slept poorly. The heat was oppressive and with her airconditioning broken, she had spent much of the night roaming the house. Trying different beds in different rooms – the student boarders she and her husband Nick, 53, took in at other times of the year were absent – she finally fell asleep around 4am.

Although she exuded efficiency at work, Papanicolaou was unsettled. Not long after giving birth prematurely, she was enduring one of the lowest points of her decade-long marriage. Her husband had been made redundant from his job in the telecommunications industry and was working late shifts in a transport job that paid less than half as much.

After four hours’ sleep, Hanny Papanicolaou woke at around 8am to messages from several clients. One wanted to know when she was returning to work after her Christmas break. Liz Welsh, who like many others had given Papanicolaou her house key, said she was away and had put out some cash for her.

Around 9am, Papanicolaou left home. She told her husband she would return before he left for work at 3pm. But instead of cleaning, as she had told him, she drove 9km to Canterbury-Hurlstone Park RSL club, signed in, and spent the next hour at the pokies. She played and lost, withdrew cash from an ATM several times, and parted with more than $400. When she left the club just after 10am, only $11.76 remained in her bank account.

Papanicolaou gambled regularly but not so much that there was ever a shortfall in the family’s grocery budget. “More or less to relax and have a smoke and play a bit of the pokies,” her husband said. “It was like smoking. It was up to her to stop.” And she did not yet seem ready. “In gambling,” his wife would attest, “I made myself calm.”

Not on this morning, though. Her bank account virtually drained, she left the club angry and guilty and drove to Peace Park, a patch of green that backed on to Marjorie Welsh’s home. From her car, she desperately tried to contact her best friend and confidante. “She’s like my sister. If I have problem I just run to her.” But despite repeated calls her friend did not answer.

Papanicolaou was not expected at Welsh’s home this morning. On her regular days she would arrive via Holden Street, leave her car in the driveway and ring the front bell. Unusually, she did not have a key to this property; normally she would confirm her arrival time from week to week, and would wait for Welsh to open the door. While she had easier access to other homes, she knew that Welsh, who had about $1600 in a bedroom drawer, always paid her in cash and that her family was away on holidays.

So she left her car at the park and jumped the fence. Unannounced and unseen, she entered her client’s sanctuary through the open back door, surprising the elderly woman when she returned from the garden. “I didn’t expect her today,” Welsh told police, “but suddenly she was in the house… she greeted me as she usually does, most affectionately. I have never seen anything else but kindness from her.” Despite the surprise appearance of the cleaner at about 10.15am, the pair received each other “like old friends”. In the kitchen of the home that she loved, this was the final moment of peace that Welsh would know.

If Papanicolaou was hoping to find something inside that might boost her fortunes – Welsh had once shocked her by revealing the multimillion-dollar selling price of her previous home – her luck continued to falter. She had taken nothing from the house while her client was in the garden. And now, suddenly, her demeanour changed. “From smiling,” said Welsh, “she became an absolute dynamo.” Grabbing one of her client’s handmade canes, Papanicolaou struck the 92-year-old repeatedly “at every available point”. Agonised, Welsh was also baffled. “I said, ‘Why Hanny? Why? Why?’ [She] didn’t say a word.” As the beating continued, she lost her balance, “fell over and begged… ‘No more Hanny, no more.’” Her pleas were ignored.

The assault was vicious and relentless. When the cane with which she was thrashing Welsh broke, Papanicolaou started with a second stick. When it too broke, she grabbed some ceramics displayed on a nearby shelf and began to hurl them at Welsh, “throwing it not just at me but down at me”. She used such force that several shards were embedded in the older woman’s head. Then she took a knife from the cutlery drawer and stabbed her elderly client, who was still coiled on the floor, six times in the lower chest and abdomen. “She was,” said Welsh, “utterly ferocious.”

The battering only stopped when Welsh remembered the personal alarm that her family had recently acquired for her. At 10.39am she pressed the button she wore around her neck, emitting a deafening siren. Papanicolaou turned off the power on the base unit, which was connected to the home phone, but it reverted to battery power and the alarm continued. Grabbing the phone’s cordless handset and the knife, which she wrapped in a cloth, she ran out the back door, jumped over the fence and climbed into her car. And Welsh, a bloodied mess, lying halfway across the threshold of her back door, with multiple fractures to her eyes, cheekbones and nose, and deep cuts through her abdominal muscle to her intestines, was left for dead.

Somehow, Marjorie Welsh found her voice. After six minutes, an operator was able to hear her over the phone’s loudspeaker on the other side of the kitchen. By then neighbours, who only knew her as “the old lady”, had appeared. The house was soon overrun with ambulance officers and gloved police. Numbered evidence markers were placed around Welsh’s home, noting the minutiae of what had befallen her: the bloodstains on the floorboards; the haphazard location of a fallen magnifying glass; a bowl of fruit that had remained on the small bench in the middle of the kitchen while mayhem erupted all around.

That Welsh was still alive seemed extraordinary. Despite her injuries and although barely able to hear (one of her hearing aids was dislodged during the assault and the other would go flat in the ambulance), she was alert, telling police that her cleaner had assaulted her. “I was surprised to see her… she had a big smile, then she viciously attacked me.” When a second ambulance arrived at 11.21am Welsh told officers, in her refined though weakened voice: “I don’t think there was a part of me that she [missed].” By 11.30am she was in an ambulance and speeding towards Royal Prince Alfred Hospital where, for the few weeks that remained of her life, her body would be continually probed, tended and mended, her extensive injuries carefully chronicled so that even the bruises that covered most of her face would be described down to the millimetre.

Her demise was protracted and cruel. “It was the most sickening thing I have ever seen,” Liz Welsh said of seeing her mother post-surgery. “Her face was so badly bruised and swollen. You couldn’t recognise her.” She spent days in intensive care. In her final weeks she endured multiple operations, developed sepsis and showed signs of persistent delirium. While she was sedated, police took 55 photos of her injuries, an extensive collection that read like a gruesome shopping list and included seven wounds to her torso and a broken little finger. She also had a collapsed lung.

When she was alert, police recorded a video statement in which she appeared vastly different to the beautifully groomed woman Papanicolaou had so admired. Her hair was pinned back messily, her neck covered in an oversized bandage and her forehead blackened; there seemed to be more bruising on her face than clear skin. But when asked if she could think of any reason why Papanicolaou had attacked her, her reply was clear: “It would be a peace to my mind if I could. There is usually a logical reason for most things that happen in this world. But I cannot see any logic to this.”

Days later, Welsh was transferred to Balmain Hospital. By then sometimes delirious, other times conscious but drowsy, she could only follow limited conversations. Her family and medical staff agreed that her chances of recovery were poor and she began to be administered morphine. She died at 10am on February 19, 2019.

As Welsh was raced to hospital, her cleaner sat in her car in a nearby street and composed multiple text messages. “Please I am going to die,” Papanicolaou wrote to her husband Nick. “I think is better for me. You never believe me anymore.” In others she told her family that she loved them and asked for forgiveness.

After she left Ashbury, Papanicolaou dumped the knife and phone in an industrial bin. She discarded her blue top near her home. Shaking, she pulled over for a cigarette. She called her husband. “She was quite hysterical and I couldn’t make sense of what was going on,” he later revealed. “She said that there’s been an accident, that [Welsh] hit her and then she hit her back. That there was blood… I tried to calm her down and said I will get the police to get there. And she said, ‘No one is going to believe me because the lady’s daughter is a lawyer’.”

Nick Papanicolaou repeatedly told his wife to stay where she was, but within 10 minutes she was home, frantic and with a long scratch on her inner arm. “She just wanted to grab the kids and hug them.” She left again soon after and her husband called police. “Someone is injured; I was concerned about the old lady.” He used a phone app to track his wife and by mid-afternoon police found her in a car park on the banks of the Georges River in Illawong.

Papanicolaou gave a long list of reasons for her presence in the Ashbury home that day. In interviews with police and during cross-examination in court she maintained, among other things, that she had wanted to revert to cleaning Welsh’s home on Wednesday that week so she had knocked on the door, even though she had no cleaning equipment. She could not remember going to Welsh’s house. She had blacked out and couldn’t remember beating or stabbing her client.

She had a similarly eclectic set of reasons for the attack, which for a long time she alleged had started after Welsh accused her of stealing $50 when she had last visited in December. “And I said, ‘What are you thinking about $50? You have a big house.’” She claimed it was Welsh who had hit her with a stick and a magnifying glass; that the ceramics had fallen and broken during the ensuing struggle; that Welsh had knocked into the fridge while Papanicolaou had tried to wrestle a knife from her; and that it was she who had pressed the emergency button to summon help, at which point Welsh had told her to leave. “‘Hanny go. My daughter is a lawyer. You are going to die.’ I really just lost my mind.”

Papanicolaou was charged with murder but pleaded guilty to manslaughter on the grounds of a “substantial impairment by abnormality of mind arising from an underlying condition”, her legal team arguing that at the time of the attack following a premature birth there were “known patterns for a vulnerability causing a major depressive order”. As her barrister Tom Quilter told the NSW Supreme Court in February 2022, when her trial began: “We don’t have a situation where somebody is attacking their arch nemesis… we have a situation where a woman with no violent history whatsoever attacks someone who she appears to have got along with.”

Under cross-examination, Papanicolaou capitulated on much that she had told police, acknowledging she had lied when claiming to have hurt her ankle after Welsh hit her with a stick; that she had lied about Welsh accusing her of stealing $50, and about Welsh pushing or hitting her or taking a knife from the kitchen drawer or stabbing her or even arguing with her. “I never have arguments with Mrs Welsh,” she finally admitted.

Papanicolaou conceded she had killed Welsh, but her testimony about her dead client was so glowing that it sounded at times like a character reference, although she was often tearful in her recollections. “We always talked. We always laughed. She always teach me about something… she always asking me how I am, how my kids. She is like a mother on me.”

The 12-member jury, eventually reduced to 10 because of Covid, heard about Papanicolaou’s poor childhood in Java and assaults when she was a child. They heard about her drug use when she moved to Jakarta, where she later met her husband before moving to Australia, starting a family and her own business. And they heard that she had no history of violence and had never sought mental health assistance. After deliberating for less than five hours – the same amount of time that lapsed between Welsh’s beating and police locating her attacker – the jury found Papanicolaou guilty of murder.

“I feel Hanny has taken something from my life, for no reason other than financial gain.” Marjorie Welsh has been dead for more than three years when her enduring words fill an old courtroom in Sydney in late April 2022. Seven of her closest relatives are seated in two rows, only metres from Papanicolaou. In prison greens, she mostly stares at the floor as crown prosecutor Christopher Taylor plays part of the interview police recorded with Welsh as she lay seriously injured in hospital six days after her attack, distrust having seared her psyche. “She has taken something from me, a quality quite irredeemable in that it was my dream world.” Papanicolaou weeps as her now long-dead client lists some of her many injuries and operations.

When Welsh mentions how much psychiatric help she will need, her daughter Liz sobs audibly. “I wouldn’t trust anyone anymore. I’m having special gates when I’m back. I’m just making it thief-proof, killer-proof,” her mother says hauntingly, unaware that she will never return home. “By God,” she says finally, “I will not forget it.”

After three long years, the day of reckoning arrives. In late May, Justice Robertson Wright finds that Papanicolaou needed money because of her gambling losses and that she went to Welsh’s home with the intention of stealing from her, knowing that she paid her in cash and that she was vulnerable. While the murder was unplanned and impulsive, the cleaner, the judge finds, intended to kill her elderly client.

Papanicolaou is given a 22-year sentence. Now divorced, she shares a cell in protective custody and sometimes assembles airline headsets. According to an affidavit presented to her sentencing hearing, she prays to God for forgiveness five times a day. Even with parole, she will not know freedom again before 2034.

“The bloody amount of disaster that this caused,” Liz Welsh says in a rare and brief interview. “It was the whole homicide squad. It was half of the police in Ashfield. It was weeks and weeks in intensive care. I don’t think you could add up the financial or emotional costs of the people who were trying to save Mum just from this one horrendous act.”

Underlying everything, though, is an irreparable erosion of trust. “The first time she lets someone in the house, trusts them, because she had met her at our house, this happens,” says Liz. While she remains devastated about the murder, for a few minutes she is happy to recall her mother’s long and mostly fulfilling years, rather than their brutal end. “Everything about her was about living a good life, not causing anyone any grief,” Marjorie Welsh’s daughter says proudly. “She gave evidence in her own murder trial, and it really sums her up.”

gamblinghelponline.org.au; Lifeline 13 11 14

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout