Between a rock and a hard place: Juukan caves, Rio Tinto and Ben Wyatt

He’s both Treasurer and Aboriginal Affairs Minister in WA. So when a mining goliath blew up an ancient cultural site, Ben Wyatt braced for the fallout.

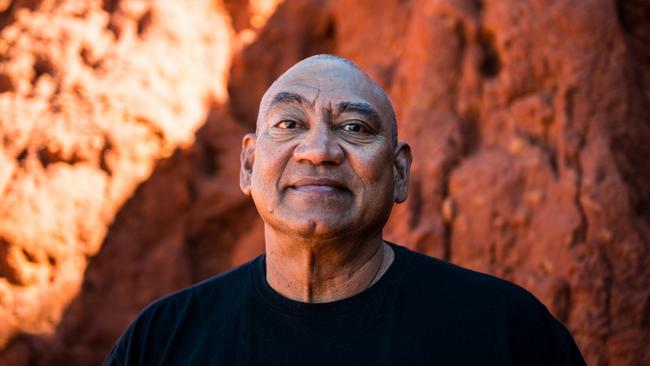

Ben Wyatt was in his Perth office in Dumas House on the afternoon of May 25, mulling over a cabinet meeting about state borders remaining shut against Covid-19. He was multi-tasking as usual – as Western Australia’s Aboriginal Affairs Minister, his job that day was to enforce the safe shutdown of remote Kimberley communities to outsiders; as Treasurer, it was his job to keep track of revenue flowing into the state’s coffers. Then a staff member walked in to deliver some disturbing news. Twenty-four hours earlier and more than 1000km away, mining giant Rio Tinto had blown up the Juukan Gorge caves on its iron ore-rich Brockman mine. Aboriginal custodians had explained that these 46,000-year-old heritage sites were important and should not be destroyed.

Media attention was soon building, international condemnation was on its way, heads would eventually roll at Rio Tinto and Wyatt was in the thick of it. “Normally with something like this there’s a lead-up,” he says, relaxing in the same chair where he got the news four months ago. “There was no lead-up in terms of my office. Up until that point, Rio hadn’t caused me any heritage grief and the [traditional owners] PKKP hadn’t had any cause to engage my office. It suggests the relationship had been working at some point.” It wasn’t what the Puutu Kunti Kurrama and Pinikura people wanted to hear at the time. “Our people are deeply troubled and saddened by the destruction of these rock shelters and are grieving the loss of connection to our ancestors as well as our land,” said PKKP land committee chair John Ashburton.

Wyatt found himself facing awkward questions. Why didn’t he know the PKKP had made last-minute efforts to save the Juukan caves? As Aboriginal Affairs Minister, did he have indigenous people’s interests at heart, or was he an apologist for global miners whose revenue he needs as Treasurer?

Wyatt is the first Aboriginal person to hold the treasury portfolio in any Australian government. If he feels the strain of balancing the Aboriginal, finance and lands portfolios, he doesn’t show it. Cheerful, gregarious and direct, Wyatt doesn’t have tickets on himself yet he’s undoubtedly accomplished: he’s a former lawyer with a masters degree in comparative politics from the London School of Economics and an officer graduate of Royal Military College Duntroon. He entered State Parliament in 2006, taking the seat of Victoria Park in a by-election triggered by the resignation of former premier Geoff Gallop; five years later, aged 37, he challenged Labor Opposition leader Eric Ripper for party leadership but withdrew for lack of numbers. After Labor’s landslide victory in 2017, a victorious Premier Mark McGowan (who has described Wyatt as a close friend and a potential future premier) gave him the Treasurer’s job.

At 46, the man once described by his father Cedric – cousin of Federal Indigenous Australians Minister Ken Wyatt – as “a smart little fellow with an interest in politics” finds himself in one of the hardest jobs on his side of the continent. It is Wyatt who must ensure McGowan has the money for his expensive Covid recovery plan. He needs every dollar, including $5 billion earned annually from mining royalties. And it is Wyatt who feels a heightened sense of responsibility to do the right thing for the state’s indigenous people.

So when the Juukan caves disaster landed on his desk, it was always a stoush that would become personal for Ben Wyatt. And despite its bruising effects, he’s not entirely unhappy about the fallout.

Two days after Rio Tinto pressed the button onthe explosion that collapsed Juukan caves, Wyatt posted a poignant message on National Sorry Day. “Sorry Day today,” he wrote. “A sombre national memory but one that my old man never let impact his fathering of me and my sister. The enduring pain doesn’t define this mob, it’s the resilience and strength we celebrate.”

Those two events – one a callous corporate act that pulverised 46,000 years of Australia’s First Peoples’ history, the other a historic scar that Wyatt’s father Cedric wore as a Stolen Generations child – have profoundly shaped Wyatt’s actions, past and present.

The caves are in the Pilbara, in the state’s mid-north. It’s country that Wyatt knows well, although – like the rest of the nation – he knew little about Juukan Gorge’s caves. Only later would he learn that DNA tests on a plaited-hair belt retrieved from inside the caves in 2014 had linked living souls to their ancient forebears.

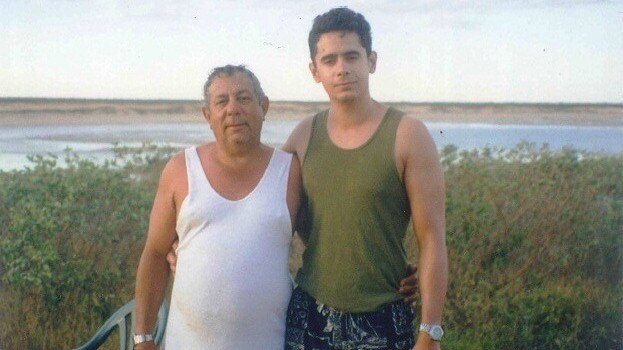

Wyatt’s father and grandmother came from Yamatji country, covering parts of the Pilbara, Gascoyne and Midwest region, “from Geraldton through to Meekatharra and up into inland Newman country”. He remembers travelling around with his father, a quick-witted, humorous and respected Aboriginal Affairs senior executive for various governments. “Being on country with Dad was probably my earliest memory. I was five or six – Dad was with the Commonwealth government and he spent a lot of time out on the Ngaanyatjarra lands, a fair distance from Laverton and Kalgoorlie where we lived for a time,” Wyatt recalls. “Life was pretty traditional for those people then, with a lot of hunting and traditional-style meetings that Dad would go to. I’d sit observing on the side, not really understanding what was going on.”

There was a cultural terrain of a troubled kind in Cedric’s past that he hid from his family for decades. Removed from his mother soon after he was born, he began life at the Moore River Native Settlement, an institution made famous by the Phillip Noyce film Rabbit-Proof Fence. “I don’t know anything about my white father,” Cedric told me in a joint interview with his son in 2009. “I don’t have much cause to go looking for him. I’m quite content to be a good dad to my son Ben.”

“The Stolen Generation was something I didn’t really appreciate until I was 15,” Ben said in the same interview. “We had been quite protected growing up, and it was only in my teens that I learnt details of how Dad had been taken away from his mother as a baby and brought up in institutions.

“His inability to express things and the fact that I didn’t know about his background was annoying,” he added. “I felt frustrated that I didn’t know about that part of our history and other people did. It’s left scars on him, like him keeping things to himself and feeling he has to solve his own problems.”

On Sorry Day this year, Wyatt posted a picture of Cedric as an infant placed on the ground a short distance from his mother, and later a picture of himself as a wriggling toddler clutched firmly in his father’s arms. Benjamin Sana Wyatt was born in 1974 in Papua New Guinea, where Cedric had gone to run remote schools and married a fellow teacher, Newcastle-born Janine. The family, which later included Ben’s younger sister Katie, returned home to teaching stints in Goldfields’ towns in regional Western Australia.

The pace of mining activity was quickening, with surveyors pushing into remote Aboriginal- occupied lands. It had led, in a shining moment of bipartisan support in 1972, to the passing in WA of the nation’s first comprehensive Aboriginal Heritage Act. Politicians had been as incensed as the Goldfields’ traditional people to see a prospector trucking sacred Weebo stones away and placing them in shop windows as adornments. State mine wardens had approved the mass theft.

The original Act offered greater protection than other state laws to places and objects important to Aboriginal people. But in ensuing years it suffered an ignoble fate under amendments that, in one case, resulted in the overnight removal without notice of 3000 Aboriginal sites from protection.

Over the past two years, in his role as WA’s Aboriginal Affairs Minister, Wyatt has worked to rewrite laws that give mining companies the right to seek a permit – called a Section 18 and issued by the Minister – to destroy sites while denying indigenous groups any redress. In the lead-up to Sorry Day, one of the most sensitive days on the Indigenous calendar, Rio Tinto used its Section 18 permit, granted under a previous Liberal government, to blow up the caves at Juukan Gorge.

As director-general of Aboriginal Affairs for five years, Cedric had to administer the very heritage laws his son is seeking to overhaul. “It was a different fight for Dad, more around the land rights agenda,” says Wyatt, who explains that in the days before Mabo and native title, Aboriginal people had no legal right to speak for their country and its heritage sites. “It’s only with the Native Title Act in 1993 that they became part of the natural conversation around land use.”

So what would Cedric – who became progressively activist and openly critical of his son’s Labor Party before he died in 2014, aged 74 – have made of the proposed new laws? “I wish he was still around to have this conversation actually,” says Wyatt wryly. He thinks Cedric would approve of the legal imperative for Aboriginal people to be consulted, and management plans developed, before “any work that may harm cultural heritage”.

“What we’ve got now in vast parts of Western Australia is that we know the people who can speak for country,” he says. “We have prescribed body corporates that hold native title and representative bodies representing Aboriginal people, so everybody knows which people they need to go to.”

Rio Tinto knew exactly who to deal with and yet it still broke faith with the PKKP peoples – and, it turned out, with most of Rio’s own shareholders. In its submission to the Senate Inquiry into Juukan Caves in July, Rio said it had binding agreements with PKKP going back to 2011 giving it “free prior and informed consent” to conduct mining on its Brockman operations. It noted how, in 2013, it obtained a Section 18 to “impact” the Juukan rock shelters and the following year the caves’ contents – including remnants of the 4000 year-old hairbelt – were salvaged. But then Rio made a startling admission: there had been four options to expand its Brockman 4 mine, and three of them would not have damaged the Juukan caves. The company admitted it chose the destructive fourth option in order to access $135m worth of high-grade iron ore. It also admitted that a 2018 archaeological report that warned of the 46,000 year-old site’s high significance was not read by any of Rio’s executive leadership team.

Five days before the explosion, PKKP advisers met with Wyatt’s heritage department and raised traditional owners’ dismay over the imminent destruction. Could the Section 18 consent be revoked? The heritage officers said it could not, and later contacted Rio to inform them of the meeting. Wyatt insists he was not told of that meeting, and the PKKP had not contacted his office. Had they done so, he would have contacted Rio but his options would have been limited. “Once Section 18 approvals are given there is no requirement for updating them and they’re not time constrained.” He says both those things will happen under the new Act, and new stop-activity orders will also be available if “imminent risks of harm” to heritage sites emerge.

Wyatt says the new Aboriginal Cultural Heritage Bill will “return the Aboriginal voice” to the management of heritage, recognising entire cultural landscapes, not merely sites or objects, and introduce the country’s toughest penalties for harming heritage, including $10m for serious harm by a corporation and $1m or five years’ imprisonment for an offending individual. Under a new tiered approvals system, permits can be issued for low-impact activities such as minor ground disturbance but high-impact activities would require prior agreement with relevant Aboriginal parties and a heritage management plan before they could be approved. “It depends on the impact on land – we’re deliberately tiering what you need to do as opposed to the one-size-fits-all Section 18,” says Wyatt. Crucially, the new laws will give Aboriginal groups the same rights to appeal approvals – rights they currently don’t have.

The proposed reforms haven’t stopped critics alleging that Wyatt is conflicted – an Aboriginal affairs Minister who, as treasurer, relies on big mining companies that can ride roughshod over Aboriginal rights. “I despise the view that’s been put [that way],” he responds calmly. “It’s not binary… I’ve had protests outside Rio’s office and at Black Lives Matter rallies saying that I must resign because I was actually defending the agreement Rio entered into with the PKKP.” A few days later, after his relative, Federal Minister for Indigenous Australians Ken Wyatt, spoke publicly about the racial abuse he receives from social media trolling, he told reporters: “To be honest, the most disgusting comments that I got were associated with supporters of the Black Lives Matter rallies.”

Ben Wyatt says he’s spent his life around people “often from the left as well as the right, who have a view about what an Aboriginal person should be”. He sees it in people who believe that Aboriginal custodians should not make deals with resource companies. When he did a round of media interviews about the Rio fallout on the eastern seaboard, “I was struck how there seems to be a view that the mining sector hasn’t changed its behaviour since the 1960s. Now, to be honest,” he adds hastily, “Rio’s behaviour feeds well into that perception, but it’s incorrect because in many parts of regional and remote Western Australia, the single biggest and often only employer is a mining company. And with some agreements, particularly in the last 10 years, you’ve seen huge flows of money into Aboriginal organisations, although a small organisation awash with cash creates its own issues.”

And here’s the kicker. Wyatt will defend to the end traditional owners’ rights to allow the destruction of sites if they decide it is in their long-term interest. “This is the challenge – for a long time Aboriginal people have fought to use their land and benefit from it. Informed consent means the ability to say no but also to say yes. Self-determination has to mean something,” he adds, as if channelling his father’s fierce resistance after decades of being told what to do.

“It’s always been a part of my memory and my dad’s that many Aboriginal people live in poverty, and from that comes incarceration, poor health and educational outcomes. If Aboriginal people go through a process – often fraught, long and bitter – and they end up in a position where they agree to land use, whether it’s a mine or a road or a rail line, then I’ll back them on that.” So if a traditional owner group chooses to let a cultural site go for material gain, then that is their right? “Correct.”

Selling his heritage reform has taken him all over the state, to hundreds of meetings. He posts social media snapshots standing shoulder-to-shoulder with Aboriginal rangers patrolling saltwater Kimberley country or with Nyoongar elders from the forested southwest. Both the Kimberley Land Council and the Southwest Aboriginal Land and Sea Council are resisting the hard sell, arguing that reform is “pointless” unless Wyatt gives Aboriginal people a power of veto over activities on their traditional land. “A Minister will still have the final say if a sacred site is important or not. How is that better than what we have now?” says KLC chief executive Nolan Hunter. “We are not trying to stop mining in WA, just asking for balance between the needs of industry and heritage protection. This draft bill certainly isn’t it, and we will do all we can to block it.”

On his regular jogs from Parliament House into the floral wilderness of Kings Park next door, Wyatt is easily recognised. As he runs past, people give him a shout out and a wave.

Wyatt nearly gave up political life. In February this year, with the state budget back in surplus, he announced he would step down before next March’s state election. It was time to draw a line under politics, get another job and give more time to his wife Vivianne, who had recovered from breast cancer, and daughters Matilda, 11, and Georgina, 10. “I don’t spend a lot of time at home, and I know I only have one window with my kids and it’s closing,” he said at the time.

A few weeks later, when Covid-19 hit, he changed his mind and even committed to contest the next election. “Suddenly we went from stable finances to huge uncertainty and a delayed budget, so I reversed my decision to bring some stability back to one of the key roles in government.” It was an immense relief to his party and to Aboriginal colleagues. Carol Innes, co-chair of Reconciliation WA, worked closely with Ben’s father on Indigenous policy issues for years and she knows Ben well. “Ben is highly intelligent, but he’s also a humble man who was willing to give it all away for his family. Just imagine if he hadn’t decided to stay on – he’s the only man to deal with Rio and the Heritage Act. We’re really proud of him.”

Paradoxically, the Rio Tinto scandal came at the right time, putting a harsh spotlight on poor heritage laws. Wyatt was quietly pleased by the international uproar among investors. “It’s never happened before. It’s been a good surprise because it wasn’t just the usual suspects in the heritage space that critique Rio. It was actually the people who control who sits on the board of Rio Tinto, being angry at what they’ve done. And that I think has been a shock to Rio as well, to be honest.”

“It’s not just anger that this has happened to an Aboriginal group but anger that this has been lost to the nation. And that’s because of the broader value that people now have of the Australian story, which in my lifetime has fundamentally increased.”

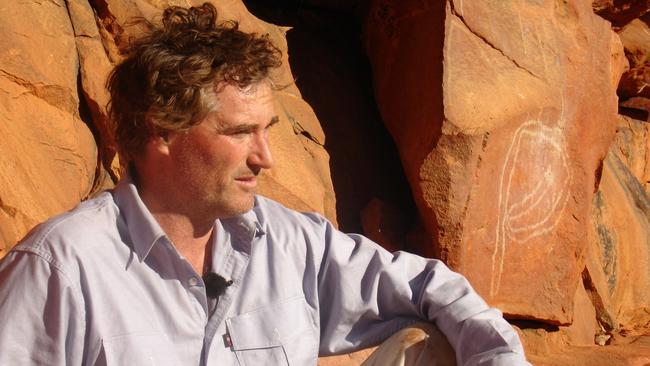

Yet Wyatt’s detractors would argue that achieving true heritage protection is some way off. Irrespective of whether minerals lie beneath, many Aboriginal sites and artefacts have intrinsic value as the tangible and spiritual story of Australia’s earliest occupation. Wyatt himself has described the Juukan caves as “a loss in global terms of a site that links modern humanity to human existence in deep history”. Archaeologist Peter Veth, who has made historic rock art finds in the Pilbara and Kimberley, says the Commonwealth must work with states to “create modern and proactive instruments that recognise the central role of First Nations peoples and the values of the extraordinary heritage of Australia”. He joins with those who ask when heritage will be managed for posterity and not viewed as an inconvenience to mineral extraction that must be worked around.

Wyatt seems perplexed by the criticism. “This is a land use regime we’re creating here,” he responds. “It puts Aboriginal people in charge of what’s a significant site, not the Minister of the day. But the Minister will have responsibility for protected areas which are clearly of national and international significance.” He names two Pilbara areas, Woodstock Abydos and the rock etchings at Murujuga, where “it’s important we say these areas aren’t to be touched”. Both have extensive rock art sites that depict extinct marsupials and “archaic faces”, believed to be among the first human images and dating back to between 10,000 and 25,000 or more years. But both areas were protected only after mass removal of Aboriginal artefacts to make way for a railway line and an LNG plant.

On a table in Wyatt’s office I spread out two maps illustrating the speed with which Western Australia’s ancient mineralised crust has been covered in mining tenements. The 1970s map shows a scattering of boxes marking new leases, largely concentrated in the Pilbara. The 2010 map is covered with thousands of big and small boxes covering almost the entire state, from the Kimberley to the southwest and east into the desert. Wyatt peers at the maps. “Well, there’s not necessarily mining activity on them all, and it’s no huge surprise because the technology in knowing what’s under the ground is getting better and better,” he says. “You’ll have areas which will remain just tenements for the rest of my life,” he adds, but admits that current gold and iron ore prices are strong incentives to mine.

Wyatt insists the mining fraternity is not surprised by what’s in the draft heritage legislation; the submissions from Rio Tinto and BHP to the federal parliamentary inquiry into Juukan caves, in which they admit shortcomings and recommend changes are, he says, “effectively what’s in the Act”. The miners’ support is hardly surprising, several indigenous groups and archaeologists told The Weekend Australian Magazine. “The heart of the legislation is approvals, approvals, approvals. It is the poor nephew to Uncle Mining,” one wrote. A native title body said Wyatt was abrogating his responsibility to manage heritage “by dumping an unworkable process on underfunded Aboriginal organisations while declaring, ‘See, they have power!’”

“The point is well made about funding,” responds Wyatt, who says money to support Aboriginal groups in making sound agreements with powerful resource companies will be put aside in the state budget. “But if the Commonwealth wants better outcomes from their native title system, I say ‘fund them better and you’ll get a better outcome’. They’ve always done it on the smell of an oily rag.”

As for Rio Tinto, Wyatt has expressed withering contempt for its “colonial mentality, brittle governance and a disconnected board”; a day or two after his public comments, three executives including CEO Jean-Sebastien Jacques were given their marching orders. “Perhaps I was a bit aggressive but I wanted to make this point that Rio holds itself out as a global company and they have board members from America and Europe. But when you get 75 per cent of your earnings from the Pilbara, you’re a Pilbara company. This is where your attention needs to be all of the time.”

Wyatt says his meetings with Indigenous landowners around the state, including with the PKKP, leave him in no doubt that Rio’s reputation is damaged. “I don’t think there’s any confidence among any of them in how Rio makes their decisions,” he says. Yet the company still has 1780 heritage sites approved for clearing, and the Section 18 permits already granted to Rio and every other land developer will not be rescinded. “Payments have been made, jobs created,” he says firmly. “To change that would be dramatic and wouldn’t get through parliament I suspect.” So will there be more significant heritage sites blasted? “I don’t know, that’s between the traditional owner groups and Rio Tinto… Some may be small sites that on the spectrum aren’t as significant as others. They won’t all be Juukan caves, that’s for sure. Rio and others are on notice these things aren’t to be treated flippantly.”

Speaking five years before he died, a proud Cedric clearly felt his son was born to complete the work he started. “Ben’s in a better position – he’s lived in the bush and he’s academically equipped,” he said. Carol Innes also thinks Wyatt is acutely aware of his responsibilities to his people. “Ben knows his father protected him from the Stolen Generation history and the stories of disadvantage. Cedric wanted his son to aspire to whatever he wanted in life. And now Ben is managing the consequences of that history.”

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout