Australian pro surfer Jack Robinson on his knee injury, WSL world championship ambitions

Riding high and ranked No.1, it looked like nothing could stop Australian Jack Robinson. But a busted knee at Bells Beach means he’ll need to perform like never before to reach surfing’s pinnacle.

Jack Robinson jogs up from the foamy grey surf at Victoria’s Bells Beach and lets out an animated “Woooooo!” It’s unlike the surfer, who’s known for his calm demeanour, to release such an uninhibited hoot. But the world No.1 has just ridden his way into the second round of the historic Rip Curl Pro – sending 11-time world champion Kelly Slater to the elimination round in the process. The commentator informs him that he’s officially made the mid-season cut. This means that alongside 22 of the best male pro surfers in the world, Robinson will progress to the second half of the 2023 World Surfing League championship tour.

As he catches his breath and regains his trademark yogic composure, the 25-year-old from Western Australia tells the camera he’s “stoked”. “But the job remains the same,” he adds. “Gotta stay on the mission.”

At this point Robinson, who had been surfing in the yellow leaders jersey since winning the first competition of the 2023 season – the Billabong Pro Pipeline Masters in Oahu, Hawaii – was in the process of pulling off a flawless start to the Australian leg of the 2023 championship tour. After winning the first comp of the season at Pipe he’d notched a third at the Hurley Pro Sunset Beach, and in Portugal he’d surfed well in messy conditions to claim the runners-up trophy.

Heading into the Rip Curl Pro at Bells Beach, which celebrated its 60th anniversary in April, Robinson was still in possession of the yellow jersey, thanks to the consistency of his first three results.

“Know Robinson’s story? It’s probably time to start telling it,” wrote The Australian’s sports reporter Will Swanton on April 3, the day before Bells was due to begin. “Because he’s on track to becoming Australia’s first men’s world surfing champion since Mick Fanning in 2013.”

Then, on April 7, the swell at Bells Beach disappears. The competition is called off until further notice – a necessary measure the WSL takes when the forecast is unfavourable, yet one that has the ability to disrupt the momentum of a surfer’s campaign. Suddenly, Robinson has an indefinite expanse of time to size up his next competitor, the Torquay local Xavier Huxtable, who grew up surfing at Bells. Huxtable, 20, had snagged a wildcard entry into the comp after winning the Rip Curl Pro Trials on April 1.

Finally, on April 9, the break fires back up and competition resumes, with spectators clamouring to watch the local boy battle it out with the world No.1. Huxtable scores the first wave, and it’s a brilliant ride. From that moment on he surfs like he has nothing to lose, which, by virtue of being the wildcard, he doesn’t.

With 10 seconds of the heat to go, Robinson paddles into a wave. It’s not unlike him to wait patiently until the last gasp of a heat to make a move, but today the stakes are especially high. In order to progress to the next round, Robinson needs a solid score of 7.36. “If he gets a snippet of opportunity right now, he could get something,” observes Aussie surf veteran Owen Wright from the commentary box. “If something presents itself, it will be an all-out attack.”

Robinson drops in, gathers speed and goes up for a layback. It’s a complex manoeuvre that requires Robinson to lean back while executing a sharp turn of direction, and when he hits the lip of the wave his board ricochets backwards, his left knee twisting with it. He’s thrown from his board as the final siren blares, signalling the end of the heat. The crowd is in shock. Not only has the world No.1 been beaten by the wildcard, but he is clearly injured. And in the back of his – and everyone else’s – mind is the fact that the Margaret River Pro, his hometown competition, kicks off in just 10 days.

In the wake of his elimination from Bells, Robinson posts a hopeful message on Instagram: “I’m resting up, healing and will see everyone at the next comp!” But behind closed doors, it’s becoming increasingly clear that that won’t be the case. On April 16, four days before the start of the Margaret River Pro, the clear favourite is forced to pull out of the competition closest to his heart.

It’s 10pm in Brazil, and Robinson is speaking in hushed tones. The rest of his camp, including his wife Julia, coach Leandro Dora and Leandro’s son Yago, who is also on the championship tour, are sleeping. In between physiotherapy sessions – he’s been doing plenty of aquatherapy to strengthen the area around his meniscus – Robinson has been keeping an eye on the comp at Margaret River.

“I’m missing WA for sure. Just watching the event… I think I probably would’ve done well in this one. But it’s just one event. There will be a lot more to come.”

This is my second time chatting with Robinson. The first time we spoke was in March. He was in Portugal, on his way to claiming second place at the MEO Portugal Pro; he was chirpy and, to borrow from the proverbial book of surfing slang, “frothing” at the thought of paddling out to compete the following day. But this evening, there’s a discernible weariness to his voice. “I’ve been going all day, doing physiotherapy, just trying to get healed up,” he says. “That’s the focus right now. It’s just part of the journey, isn’t it? Having these little bumps.”

Ask anyone in the world of competitive surfing, and they will tell you Robinson’s mindset is one of his greatest assets. On tour, he’s known as a bit of a shaman – he meditates cross-legged on the beach before his heats, and in the water his ability to remain calm under pressure is what makes him such a fierce competitor. But nothing tests the emotional strength of an athlete quite like an injury.

I ask Robinson to talk me through that fateful heat at Bells. “Surfing against the wildcard, it’s kind of different,” he says. “You think you have to do more against guys who aren’t on tour because you don’t really know them as well; you’re not as familiar with how they surf. I was kind of thinking about it a lot and then I went into the heat and I don’t know, it was just real… funny. I was almost trying to force it a little bit maybe. I left it until pretty late to pull out [of the Margaret River Pro], because I was like, ‘I’m still going to surf it. I don’t care about the pain’. I thought I would’ve blown out the whole knee actually on that wave [at Bells], because it was such a twist and a weird angle.”

He pauses, as if to pull himself out of the negative headspace that is replaying a moment in his head that can’t be undone. His tone, which implies an “everything happens for a reason” mentality, makes it clear that Robinson’s mental training – the meditation, breathwork and gratitude practice that’s become core to his regimen in recent years – is showing up when he needs it most. “The injury… I didn’t want it to happen. But it almost needed to happen the way it did. This time last year during the tour I didn’t have as much energy going into the second half. I was maybe not as excited. And now I’m just so excited to come back... You almost transform yourself when you have the time off and you’re in a different place.”

He purports to be in a different place mentally, but mathematically he’s in different territory too. After Bells he dropped to No.2 in the WSL rankings, having been eclipsed by Brazilian rookie João “Chumbinho” Chianca. At the time of writing this, the Margaret River Pro has concluded and Robinson has been pushed to world No. 3.

“Well, it’s nice to have it,” he says of the yellow jersey – which is technically a rashie. “But if you don’t have it you can’t freak out either. It doesn’t really matter as much in my mind… let’s just try and get it back for later in the year when it does matter at the end. It’s part of the game. Sometimes you want it way more too when you don’t have it.

“I’m going to be completely different going into the next part of the year. Like, I might be surfing in a bit more pain and stuff, who knows, but that won’t even worry me. I’ll be fine. I’ll just be channelling my energy better.”

Robinson joined the WSL Championship Tour in 2020, after winning the final event of the men’s qualifying tour in Oahu in 2019. But sports people have known his name for much longer. Since 2006, when, as an eight-year-old, he took out the under-12 division of the WA state surfing championships, his name has been uttered in the same breath as prophecies like “the future of surfing”.

While most kids his age were practising their pop-ups on foamy beach breaks, Robinson was paddling out to surf triple overheads at The Box, a notoriously hard and fast reef break about 200m off the coast of Margaret River, where the Margaret River Pro is held. This town is where he spent most of his childhood after moving from Perth with his family at age six to focus on his surfing career. With a savant-like ability to read the ocean – intentionally instilled by his father and former coach, Trev – and a collection of junior titles, Jack became the poster child of Australian surfing.

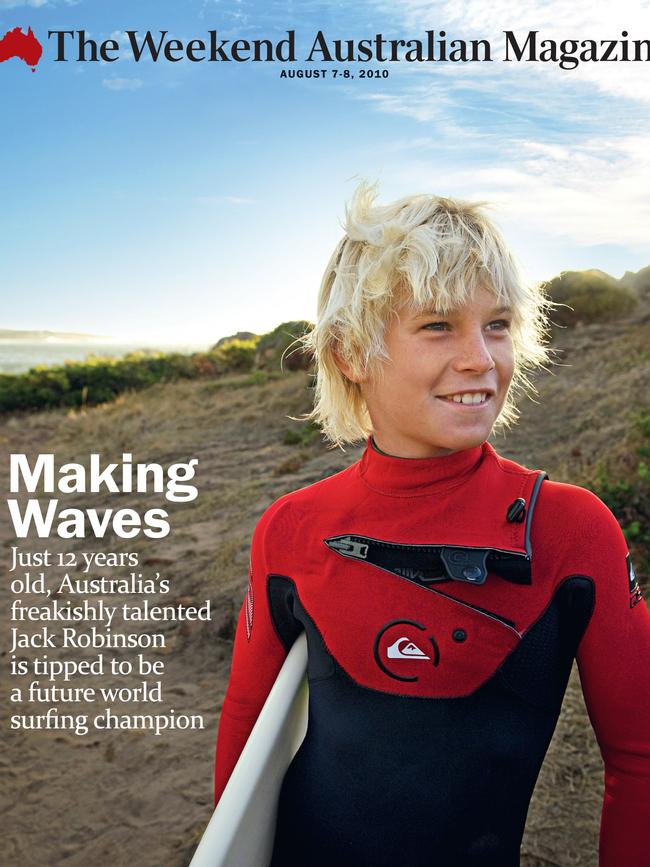

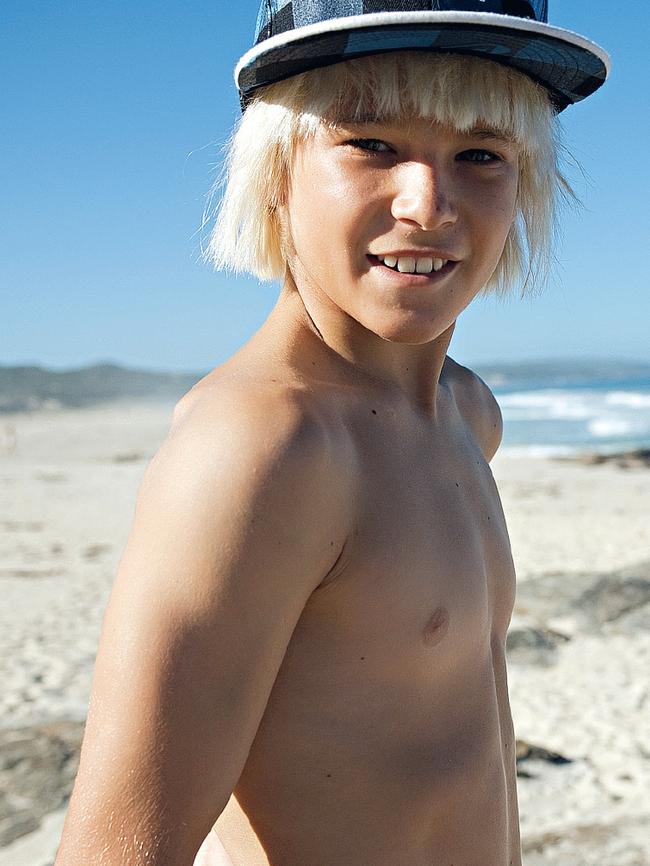

Naturally, word of his fearlessness spread beyond surfing circles. In 2010, two years before he became one of Surfing World’s youngest cover stars, a 12-year-old Robinson appeared on the cover of The Weekend Australian Magazine, sporting a shock of blonde hair and a cheeky grin. “Australia’s freakishly talented Jack Robinson is tipped to be a future world surfing champion,” the cover line declared.

“I was actually looking at that a couple of months ago,” smiles Robinson when I raise it during our first conversation in Portugal. “It kind of put me on the map. I remember it was the first time everybody started to hear about me.”

The story charted Robinson’s rise, and the voice of his father featured prominently. “We have lived and breathed every stage of his development,” Trev told writer Fred Pawle, adding that he was “hand-rearing a racehorse”. Surf publications everywhere dined out on the quote for years.

But no one carries the mantle of being “the future” of a sport without feeling the weight of that on their shoulders. And certainly, Robinson has experienced – and struggled with – the toll of expectation in the past. “Is the mission that he’s on his, or his dad’s mission? Is the pressure that’s being applied to him as being the best in the world going to create expectations in everyone’s mind, including his?” asked Ian Cairns – who was influential in establishing the pro circuit in the 1970s and early ’80s – in that 2010 cover story. “History says that most of the young brilliant talents don’t make it.”

For a few years, as he was trying to qualify for the championship tour, the pressure appeared to get to Robinson. “There’s so much talk and so much hype, and when you keep hearing it all the time it sticks in your head. I had it when I was a kid and I got caught on it a bit,” he admits. Early on in his career, for example, he was dismissed by many as a “big wave guy” – someone who can surf heavy reef breaks skilfully, but struggles to score points in smaller, lumpier conditions. “As a teenager, I lost a lot of heats. And I was like, ‘Ahhhh, why isn’t this working?’ I would get really fired up. There are so many different emotions, and I think learning how to control the emotions… that’s the biggest part.”

Trev, well known to all on the circuit as an idiosyncratic figure – he was described in one surfing publication as “famously new-age” – stopped coaching Robinson, and travelling with him, at the end of 2018. When conversation shifts to the man who taught him how to read the ocean, Robinson acknowledges his father but is reluctant to talk about their relationship. “We haven’t chatted in a while,” he says. Before this interview, the most Robinson has spoken about his dad is in the Apple TV+ series Make or Break, which follows the world’s top surfers around the championship tour. “Last year… wasn’t an easy season,” he says in the documentary, in reference to 2021. “I almost fell off the championship tour. I had to come through heaps of things with, you know, Dad – he’s always asking me, ‘Who you got around you, why can’t I come to the next event?’ – because he always used to be a part of it. But I just asked him to stay away. This year, I’m just doing my own thing. I’m only having certain people around.”

“Yeah, I spoke about it a little bit in the documentary,” he reflects now. “It’s not easy growing up; it’s super hard sometimes. But then also, these things make you stronger for the future. Nothing will ever be perfect and you have to go through these experiences so you know how to evolve and move through to the future.”

-

“Like you said in your last article back in the day, it’s like hand-rearing a racehorse. The horse is going to win eventually. And he did.”

-

While some armchair experts suspect Robinson’s success has more to do with him being this clean, fresh face of modern surfing than the fact he’s the best surfer in the world right now, on tour, his contemporaries – including friend and opponent Griffin Colapinto, the current world No.4 – admire what he’s been able to overcome in his personal life, and how these triumphs have strengthened his ability to perform in the water. And when he’s soaring, it’s a world-class show. “I really admire everything that he has had to overcome in his teens,” Colapinto tells this magazine. “He had a lot of family issues that were weighing on him pretty hard, so to see him overcome them is really inspiring.”

Trevor Robinson says he’s reluctant to add more “noise” to the conversation, out of respect for Jack and his surfing career. “I love him to death, no matter what,” he says. In a wide-ranging phone call, he alludes to a difficult past few years between father and son, and his own personal issues. “I spent 20 years with Jack, developing him... I gave my life to it,” he says. Recalling The Weekend Australian Magazine’s 2010 cover story, he adds: “Like you said in your last article back in the day, it’s like hand-rearing a racehorse. The horse is going to win eventually. And he did.”

Does it make him proud to see what his son has achieved? “Absolutely, look, it brings a tear to my eye,” he says, as his voice catches, “straight to the throat there.”

I ask him if he thinks Jack has what it takes to be Australia’s next world champ. “No one ever owns a crystal ball,” he says. “You can only ever own your preparation... but he’s got the willpower. He’s got the skill-set to do it.”

Says his son: “Maybe one day I’ll make a big documentary about my own childhood, and show [my experiences] growing up. It’d be cool because I feel like everyone has a story. People who are great at something… it never comes easy. Yeah, I think I’ll show that one day.”

In mid 2021, Robinson began coaching with Leandro Dora. A former pro surfer from Brazil, Dora is widely regarded as the man who has helped to transform Brazil into the world’s most competitive surfing nation; right now, the world No.1 and No.2 are Brazilians. A decade ago, when Mick Fanning and Kelly Slater were in their prime, those top spots were dominated by the Aussies and Americans.

Dora is known for his progressive coaching philosophy. “Surf is mystical; it is a mix of dance and meditation,” he told the WSL in 2017. Mindfulness, diet and “doing it for the love of it” factor into his teachings; Dora has helped Robinson gain control of his emotions, which has been key in his rise up the rankings.

In an email, Dora says that he had been following Robinson for a long time, “and already had some ideas on how I could help him... He came with a very heavy burden of having to win events and be among the best in the world. He’s always been very good from a very young age and naturally, the pressure comes and that weighs on his shoulders and in surfing that means a lot. I think the most important thing about working with Jack was staying conservative. [We made] adjustments to equipment, physical training and posture related to an athlete’s general demeanour. Because surfing is a dance with the wave, you must be free, light, loose and strong and focused at the same time.”

Robinson trains with Dora’s son Yago, the current world No.9. In addition to being competitors, they are good friends. On social media, the brotherly relationship between them comes through in videos of them goofing around, as well as clips of them egging each other on in the surf.

Another pivotal member of Robinson’s inner circle is his wife, Julia Muniz. The pair met in 2018, when Muniz was 19 and Robinson was 20, and they married two years later. Now Muniz, a Brazilian-born model, travels everywhere with him; at every comp, she’s cheerleading from the beach. “I think she wants the heat more than me sometimes,” says Robinson with a laugh. On Instagram, where Robinson posts videos of himself shooting through tubes, Muniz is first to respond with a fire emoji. She’s not the only one showing love in the comments section. While the history of men’s surfing is characterised by fierce – and sometimes unfriendly – rivalries, the new generation of athletes on tour seem more invested in good sportsmanship and excellent surfing than they do the politics.

Well, mostly.

“Some guys have little puppets around them, and they will talk crap,” says Robinson. A 2022 heat against Brazil’s Italo Ferreira, the world No.16, springs to mind. After being beaten by Robinson in a heat at Bells Beach, Ferreira, who felt he was unfairly scored (a belief that was reinforced by his team), snapped his board in half and stormed into the judges tower to protest their decision.

“But I guess that makes it fun,” says Robinson with a grin. He may be the shaman of the surfing world, but his antagonistic instinct hasn’t completely disappeared. “Sometimes… it’s good to talk shit.”

Professional surfing has undergone a major cultural shift since the turn of the century. Back then, the end of a competition would often mark the beginning of an alcohol-fuelled bender. But today, the world’s best surfers train just as hard as runners, swimmers and martial artists, which makes sense, given surfing made its Olympic debut at the 2020 Tokyo games. With this season marking the qualifying year for the 2024 Paris Olympics, for those on the tour there’s even more at stake. Forty eight surfers will compete at next year’s games (24 men and 24 women); in the mens, 10 quota places are determined through WSL results, while the remaining 14 are decided at events held throughout the year by the International Surfing Association (ISA), which runs the World Surfing Games. “That’s definitely in the big picture. I want to be there,” says Robinson of the Olympics. “Besides the world titles and event wins, that’s the biggest thing that’s up there.”

“I feel like it’s changing, with the new generation of guys on tour,” observes Robinson of the sport’s culture. “It’s like a lifestyle shift. I mean, guys were partying so hard back in the day, and some of the guys that would party really hard… they would still surf really good. But I don’t think they would be able to do it for a very long time.”

A name that comes up many times in my conversations with Robinson is Kelly Slater. The American has won the most world championships of any surfer ever, and at 51, he’s still competing on the tour. Famously, he’s not a partier.

For decades, the surfing world has been asking itself the question: Who is the next Kelly Slater? Everyone has an opinion. In terms of championship wins, Australia’s Stephanie Gilmore is creeping up on Slater’s record – she has eight world titles. But if you ask Slater himself who’s next in line for this throne, there’s one surfer he doesn’t hesitate to heap praise upon. And that surfer is Robinson.

“Jack is super determined; he’s really headstrong,” Slater revealed in an episode of Make or Break. “When I see him surf, I kind of think I’m looking at me when I was younger. He’s still really pushing himself in all situations to get better. He seems to be the guy who backs himself more than anybody that I’ve seen.”

Robinson is keenly aware of how Slater perceives him. And he’s not at all intimidated. “I love it. It’s super cool. I think I looked at it as pressure before. But now, it’s like, ‘OK, I want to beat him’,” he says, flashing a goofy grin. “I’ve learned a lot from him. He’s one of those guys that brings out the best in you. I feel like I can relate to him.”

Every five years or so, there’s a generational shift on the men’s WSL Championship Tour, wherein a new crop of young guys move through the rankings to usurp the men they grew up idolising. As we approach the midpoint of the 2023 season later this month, it’s clear we’re in the flush of one of those years. The top ten is dominated by young guns, and after years of speculation around whether or not he would grow into the world champ the surfing industrial complex willed him to become, Jack Robinson is at the vanguard of this new generation.

Will the injury he sustained at Bells Beach threaten to derail his 2023 world championship dreams? For a surfer without his mental strength, the answer might be yes. But Robinson feels otherwise. “I’ll have way more energy coming back ’cause this has kind of reset me. And I think I need that going into the next part of the year. I’m only going to be focused on me,” he says. “I’m thinking about the big picture. I’m not just coming back for one or two contests, I’ve got a bigger goal in mind.”

Now, he’s staring down the barrel of the Surf Ranch Pro. It’s the only stop on the WSL tour that’s held at a man-made wave pool – that man being Kelly Slater, who opened his 700m long pool in Lemoore, California, in 2015. Although Robinson is not yet back surfing, at the time this story goes to print – a week before Surf Ranch Pro is due to begin – he is hopeful about making an appearance.

So what is the bigger goal? “My eyes are set on being the world champion, that’s the main thing,” he says. If he’s to get there in 2023, Robinson needs to return to competition quickly in order to maintain his spot in the final five – only the top five surfers progress to the Rip Curl WSL Finals in California in September, where the world champion is decided. “There’s so much more I want to show,” he adds with conviction. “I’ve got a lot more potential left to fulfil.”

I recall an anecdote that Robinson brought up in our first conversation. Given all that he’s achieved, the people he’s proved wrong and those he’s done proud, it feels particularly poignant. “I was in Hawaii before the Pipe Masters started, and, you only get asked these questions sometimes, you know, only some people ask them. Anyway, I was there with [Italian surfer and current world No. 10] Leo Fioravanti, and it was so random, [actor] Matthew McConaughey walked over from next door, to the house we were staying at. He started talking, then he looks at me and goes, ‘Hey, did you think you would be here when you were young?’

“I was looking around, looking at Pipeline, looking at our house, and then I looked at him and I’m like, ‘Yeah, kind of, I did imagine this’.” At that, a boyish grin spreads across his face. “That was a really, really cool moment. You don’t often say it, but you feel it. You’re like, ‘I want to be there one day’. And then it happens.”

Make Or Break is now streaming on Apple TV+

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout