‘Auschwitz is not a fantasy to me’: How Lily Brett has turned family tragedy into Treasure

Lena Dunham and Stephen Fry bring the memory of their murdered ancestors to the screen in Treasure, a timely adaption of Lily Brett’s acclaimed novel. It’s a film, the author says, that turns the tables on Jonathan Glazer’s The Zone of Interest.

Children born to parents who survived the Holocaust inherited a world of ghosts. There were the murdered relatives they would never know. The gaping holes left by stories their parents were unable to tell. Many second-generation survivors grew up hearing their parents scream in their sleep. Some worried that it was all their fault.

Lily Brett was born to two parents who survived the horrors of Auschwitz-Birkenau. She has written, largely, about the Holocaust across ten books of poetry, six works of non-fiction and seven novels. But some stories are so haunting they are inscribed in the body. This she realised when she found herself in Poland, sitting on a toilet that once belonged to the Auschwitz commandant Rudolf Hoess, with a bladder that refused to budge.

“I sat down on the toilet and thought, ‘Oh my god, This is where Rudolf Hoess sat’.” Brett leans in towards the screen, her brown eyes, always enormous, grow wider still. She is talking to The Weekend Australian Magazine from the home in Manhattan’s Lower East Side that she shares with her husband and creative collaborator, painter David Rankin, who is by her side throughout our video call. “No matter what I did, my bladder was paralysed. I just sat there and thought, ‘I’ve got to get out of here. I can’t do this’.”

It could be a scene out of her semi-autobiographical 1999 tragicomic novel Too Many Men, which is soon to be reissued as Treasure, to coincide with the release of the film of the same name. The novel follows the characters of Ruth Rothwax, a music journalist (at 18, Brett began her career at Australia’s first pop magazine, Go-Set, and covered the 1967 Monterey International Pop Festival, developing an international reputation interviewing the likes of Janis Joplin, the Rolling Stones and Jimi Hendrix), and Edek, her Holocaust-survivor father. The pair journey to Poland, where Edek was enslaved at Auschwitz, to trace their pre-war family history. It is while travelling that Ruth becomes haunted by the ghost of Rudolf Hoess, and has intimate, often very funny conversations with him while he struggles to make it into heaven.

The ghost of Hoess does not make it into heaven. Neither does he make it into the film adaptation of Treasure, which stars Lena Dunham as Ruth and Stephen Fry as her father. Fry is enchanting as Edek, who is sweet, often infuriating, and a somewhat unwilling participant on the journey that Ruth has curated for them. He does not want to return to Auschwitz - place Brett has visited herself “at least 6 or 7 or more” times - or to his family home. But he knows the Poland of his past, and will not allow his daughter to travel there alone. Along the way, he charms everybody he meets, whether it be their driver (played by Polish actor Zbigniew Zamachowski, of Krzysztof Kieslowski’s Three Colours series) or two flirtatious women who become uninvited guests on the father-daughter odyssey.

Stephen Fry is in the back of a car driving across central London when he dials into our call. He’s a little late. When his voice does come down the line he apologises profusely for dialling the wrong number several times, and calls himself an “absolute idiot”. The voice could not be more familiar. Not only have those erudite tones carried a myriad of memorable roles in film and television, they have been the soundtrack to the road trips and school runs of a generation through his narration of seven Harry Potter novels. So it’s somewhat self-effacing when, asked why he took the role of Edek, he replies: “Most of what I do, to be honest, is play a supporting role in which a pompous lawyer, or similar, is required.

“And I’m very happy to provide that,” he clarifies. “But occasionally I’ll read a script and think, ‘Gosh, that’s a real role’. And this one screamed out at me because I saw my grandfather in it.”

While Fry’s grandfather was Hungarian, not Polish, his portrayal of Edek Rothwax was informed by what he describes as the “miracle” of his grandfather’s compassion and vitality after his experiences during the Holocaust.

“When you’ve survived the horrors of Nazi persecution and life has afterwards been kind enough to send you to a free country, and allow you a measure of prosperity that seemed impossible when you were a prisoner – either of the ghetto, or even worse, of the camp – there are different ways [you can respond],” he says. “Some retreat into privacy and a sense of not wishing to trust people, and others kind of open their arms to life and are full of zest. And my grandfather was like that. He had a way of charming strangers, which was so similar to Edek. So I did try to channel my memories, as well as work on what was in the script.”

Lily Brett’s anecdote about her unyielding bladder is not a scene from one of her books. In March 2015, she and Rankin were among the first people to be shown through the house that Rudolf Hoess and his family occupied during the war. When it was time to leave she realised she needed to go to the bathroom. Cue frozen bladder.

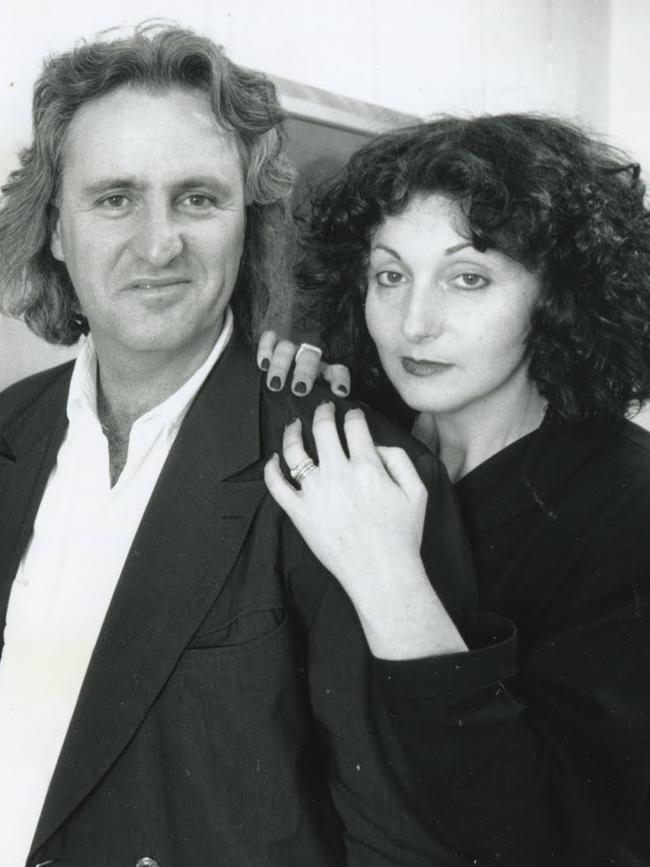

Towards the end of their visit, the couple were asked if they wanted to see something that no one had seen before. Of course they did. Brett has been writing about the Holocaust for most of her life, and has a private library of more than a thousand titles on the subject. “People come out of there pale,” she laughs. She has described this subject – being born in a displaced persons camp in 1946 to parents who survived years of imprisonment in Nazi ghettos, labour camps, and Auschwitz – as the single most defining aspect of her life. She met her British-born husband, who made his name with large-scale abstract expressionist works, in Melbourne. Immersed in her family history, Rankin would go on to paint arresting portraits based on stories from the Holocaust’s concentration camps, as well as portraits of Brett and her mother; post-Holocaust Madonnas.

And so the couple were led into a laundry at the back of the house, where, beside an old concrete sink, a young man pulled aside a makeshift cabinet attached to the wall. The cabinet covered a hole that led to some roughly built steps down to a vast bunker where the residents of the house must have planned to hide towards the end of the war.

“‘It was very spooky down there,” says Brett of the bunker that stretched out under the garden and beneath the strawberry patches. These are featured, with the house and the characters who occupied it, in Jonathan Glazer’s Oscar-winning film The Zone of Interest.

How did Brett, as someone who has been to the house, and spent years researching and writing about Rudolf Hoess, react to Glazer’s film? “I found it extremely disappointing,” she says frankly. “A film about Jews with no Jews in it is very handy for many people. I could not believe that their main point was that Mrs Hoess used the underwear of dead Jews… I mean, that’s not the point. The point was how many thousands of people were being burned to death every day and how you can see, you can feel and you can smell and you can hear everything.”

In Too Many Men, Ruth has carefully curated a trip that will take her to the ruins of the Warsaw Ghetto, to Edek’s former home in Łódzź (the birthplace of both of Brett’s parents) and to Auschwitz. They discover that the family who have occupied Edek’s former home since 1940 still have some of their belongings. When her intricately laid plans are repeatedly thwarted by Edek’s avoidant nature, and his sprightly flirtation with two women he befriends, the differences between first and second generation Holocaust survivors emerge. The first generation wants to forget and move on with life; the second needs to know what happened.

Lena Dunham is the creator of Girls, the generation-defining series whose lead character, New Yorker Hannah Horvath, famously utters in the pilot episode: “I think that I may be the voice of my generation. Or at least a voice. Of a generation.”

Dunham brings her Millennial-wry sensibility to the character of Ruth. There is plenty of thematic resonance between her writing on Girls and Brett’s Ruth, who battles to control her irritation towards her father and struggles with an eating disorder and self-harm – all while uncovering the long-buried horrors of her parents’ past. Her interpretation of the character earned Brett’s approval. “My jaw dropped several times watching Lena,” Brett says. “I thought, ‘Oh my God, that is me’.”

It turns out that Dunham, who is also a producer on the film, grew up a few blocks from where Brett raised her family in New York. “We have been circling each other always, and to have a chance to bring her prose and inner life to the screen was irresistible,” Dunham tells The Weekend Australian Magazine.

Brett is “a remarkable voice not only chronicling the post-Holocaust Jewish experience but of the female experience,” adds Dunham, who has spoken before of Jewish family murdered in 1941. “I consider her the feminist companion to Philip Roth, whose work is in dialogue with hers for me. Her writing is palpably loving yet sharp. To read her is to know her, and to know her is to love her.”

Brett was thrilled to have a German director and a German crew adapting her novel, saying that she knew within 30 minutes of meeting Julia von Heinz that she was the right person to direct the film, which premiered in Berlin earlier this year and will appear in Australian cinemas next month.

Reviews of the film so far have varied wildly. The Guardian lamented the “well-intentioned” but “muddled” tragicomedy, while in other places the film is accused of “mawkishness” and “sentimentality”. But The Times praised performances in a four-star review that seemingly appreciated how trauma can manifest sometimes in odd ways, including bonhomie.

Heinz, who reportedly struggled to get the film financed initially, had a Jewish maternal grandfather but she says that on her father’s side “there was ... guilt in the family, which was very hard to reconstruct for me, and to find out, because no one talked about it”.

The financing difficulties were apparently quashed once Dunham was on board and Heinz told industry magazine MovieMaker that early questions she had to field such as “Aren’t we over it? Do we really need another Holocaust film when we already have thousands of them?” ceased then too.

Along with Heinz’s 2020 Oscar-nominated film And Tomorrow The EntireWorld, and her 2013 film Hanna’s Journey, Treasure explores the impact of the Nazis on subsequent generations. “In Germany we learned so much about the war at school,” says Heinz, talking to us over Zoom from Berlin. But, she adds, “families were able to be silent. That is a crazy thing. Most of the third generation think their grandparents were in the resistance, were victims themselves, or helped other victims. Eighty per cent of people think that about their grandparents, which cannot be true. There’s no family who can find the papers, who can find all the documents that prove that their grandparents might have been guilty, might have been predators. Eighty years later, Treasure is a film about that too.

“So I still feel we are just at the beginning of this in Germany, although we talk and learn so much about it. And it’s why I still feel a need to make sense of it and use my art as part of that dialogue.”

Heinz has a different view of The Zone of Interest, which is that the “banality of evil” shown in Glazer’s film allows the audience to create the world of the camps “on the other side of the fence”. Where Treasure shines, she argues, is in its accessibility for young people, the emerging fourth generation.

Brett is masterful in tempering the dark with the light in her work, as if the aforementioned Philip Roth had a love child with Nora Ephron.

“People have asked how I can write such serious and often very sad things and then make somebody laugh three pages later,” she says. “Well, I’m not laughing at the sad thing that happened. I’m laughing at something else. And I’ve often thought I need to.”

Those who have read Too Many Men will know that the choice of Dunham and Fry to play Ruth and Edek is masterful casting. Heinz says the pair continued to look, and behave, like father and daughter in between takes. Their onscreen dynamic, particularly in the breakfast scenes, carries the kind of levity that is critical to Brett’s novels. Humour played a part off-screen, too. With parts of the film shot at Auschwitz, where both of Brett’s parents were imprisoned and where Fry’s ancestors were murdered, a kind of gallows humour emerged as a coping mechanism.

“I made a sort of joke when I was with Lena and we were standing there for the first time,” Fry confesses. “Lena said, ‘What is it about that name even, Auschwitz?’” Fry’s voice shudders with the weight of the name and the horrors that it conjures.

“And I replied to her, ‘I suppose if you were sent here, at least you knew that you were at the Harvard of death camps.’ It’s a terrible thing to say, but also a very Jewish thing to tell a joke that is kind of funny but also deeply painful.”

The movie took over ten years to make – spanning the Covid pandemic, the catastrophic events of October 7, and the war in Gaza that followed and still rages. “October 7 made us decide to finish the film earlier and have it out at Berlinale [International Film Festival],” Heinz says. “The arts community has been so heavily divided about this issue, so we felt that our film could be a voice in the dialogue.”

Fry, whose performance in the film was described in one review as “enormously risky”, is an atheist, and admits he is mostly viewed as quintessentially English. “I don’t feature on people’s ‘Jewdar’,” he laughs.

There is a scene in Treasure in which the characters drive into Łódzźand the camera cuts to a flash of graffiti on the side of a building – a Star of David strung up on a gallows. The film is set in 1991 but the graffiti feels very current, not unlike the examples cited by Fry in his 2023 Christmas message, and similar to those that have recently sprung up in Brett’s hometown of Melbourne.

“I certainly know that antisemitism is rising globally at a ferocious pace,” Brett says. “And it’s just about impossible to comprehend. I find it very frightening that it’s spread so rapidly. And I never thought it would get to Australia, ever. I now know very differently.”

She attributed the “terrifying” rise of anti-semitism in Australia to individuals who simply “don’t know the history” of Jewish persecution.

“(Auschwitz) is not a fantasy to me. I go there repeatedly (although) much less often than I used to. I used to feel the need to go there a lot.

“I think I go there in the same way that other people go to church or a synagogue … because the only people that I’m related to - apart from my parents and my family - they’re all dead but they’re all there, and I feel as though I am showing them that I care and that I love them, and there’s something about the place that I feel part of.

“It’s very, very hard to explain. It is an appalling place.”

Brett’s trademark curls frame her face, razor sharp cheekbones beneath those enormous eyes, as soulful and haunting as they ever were. Her eyes are never bigger than when painted by her husband; he’s done it so many times he could fill a small museum with his portraits.

Rankin, the 1983 Wynne Prize winner, has held more than 100 solo exhibitions – in 2005, a major retrospective of his works toured Australian galleries – and is represented in public collections including the National Gallery of Australia and the Art Gallery of NSW.

The influence Rankin and Brett have brought to each other’s work is profound. Brett’s first two books of verse, The Auschwitz Poems and Poland and Other Poems, contain a series of Rankin’s etchings that are also held at the Jewish Museum of Australia in Melbourne. The Black Coat, his painting of Brett which hangs in the National Portrait Gallery in Canberra, is, he says, “an image of loss, pain, survival and redemption”.

He met Brett when she profiled his wife, the poet Jennifer Rankin, who was dying of cancer. Brett was married to musician Rob Lovett, and her two children, Paris and Gypsy, became friendly with Rankin’s daughter Jessica. Once, after Jennifer had passed away, Brett and Gypsy arrived to take Jessica on an outing.

“I opened the door and Lily was there,” Rankin says. “When I looked at Lily, all of a sudden the cosmos rearranged itself and my head was full of colours. And I could not believe what I was looking at. I said to her, ‘I’ve been dreaming about you all my life. And, you know, you were born to be with me’.”

Brett replied, nonplussed: “Well, I’m here to pick up Jessica.”

While Rankin describes his raging love, a small smile tugs at the corners of Brett’s mouth, like she’s humoured by the intensity of his love for her. “I was totally, totally dotty about Lily,” he continues. “And I said to her, ‘If you don’t leave your husband, I’ll buy a caravan and I’ll park it on the verge outside your house and I won’t give up until you capitulate’. That was my courting approach.”

It worked. Brett and Rankin have been married for over 40 years and have a blended family of three children and eight grandchildren. Their son, in a realisation of Brett’s late mother’s dream, is a doctor, and their two daughters are a publicist and an artist, respectively.

Since 1989 they have lived in New York, now splitting their time between the Lower East Side and Shelter Island. Brett has always given advice to Rankin on his paintings and he’s returned the favour with her manuscripts, when she’s ready to show them. Creativity, for them, is part of a very down-to-earth existence. “I think almost everybody is creative in one way or another,” Brett says.

Yet as down-to-earth as they are, there is a spiritual dimension to their work. Rankin’s friend Peter Carey, the New York based novelist and Booker Prize winner, has observed that spiritual concerns may not be shared in the Sydney suburbs of Rankin’s 1950s upbringing. Carey writes in his introduction to Dore Ashton’s 2013 monograph on David Rankin’s long career, “If it is uncool to do battle with the spiritual as Kandinsky and Mondrian have done before you, it is quite likely you just don’t know. Or, if you are David Rankin, you do not care.”

Rankin recalls a moment when Brett’s father, Max, walked into an exhibition titled Pictures of Lily on opening night. “We were surrounded by the paintings, friends, and collectors. Max, making a sweeping gesture, stated in a loud voice, ‘I have such a beautiful daughter. Look what he does to her’.”

The anecdote belies the pair’s close relationship. “Max and I were soulmates,” says Rankin.

Brett’s smile, which fades at certain points in our discussion, returns full beam whenever we talk about her late father, who died in 2018, four months short of his 102nd birthday. The character of Edek is a father figure who crops up across a number of Brett’s novels, mostly based on Max. There are obvious parallels – their kindness, mischievousness, love of cake, and big-busted women.

When Brett sat down for her first screening of the rough cut of Treasure, Fry’s performance left her in tears. “He was so like my father. I cried. Because everything, his gestures, his voice, the way he held his head. I mean, he never met my dad… And it really made my dad feel alive to me. I was a wreck.”

This makes Fry very happy. “I’m just thrilled that she feels that. Because if no one else likes the film, at least I haven’t upset the creator of this character. Which is something!”

Max Brett moved to New York when he was 89 years old and lived the rest of his life surrounded by his beloved family. “It was amazing. He was here with us on the Lower East Side until he was almost 102. He could not believe he had this big family. For his 100th birthday we hired a magician, because my dad loved magicians. And my dad laughed more heartily than the children, the grandchildren.”

The magic in the film Treasure is its ability to bring love and light to a sorrowful subject. “I’m at my happiest when I’ve written something funny,” Brett says. “My dad taught me something that was very valuable, and that was that laughter could pierce pain. And I think it’s really true.”

Treasure has an Australian release in cinemas on July 18. The novel Too Many Men has been reissued as Treasure by Penguin Australia.

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout