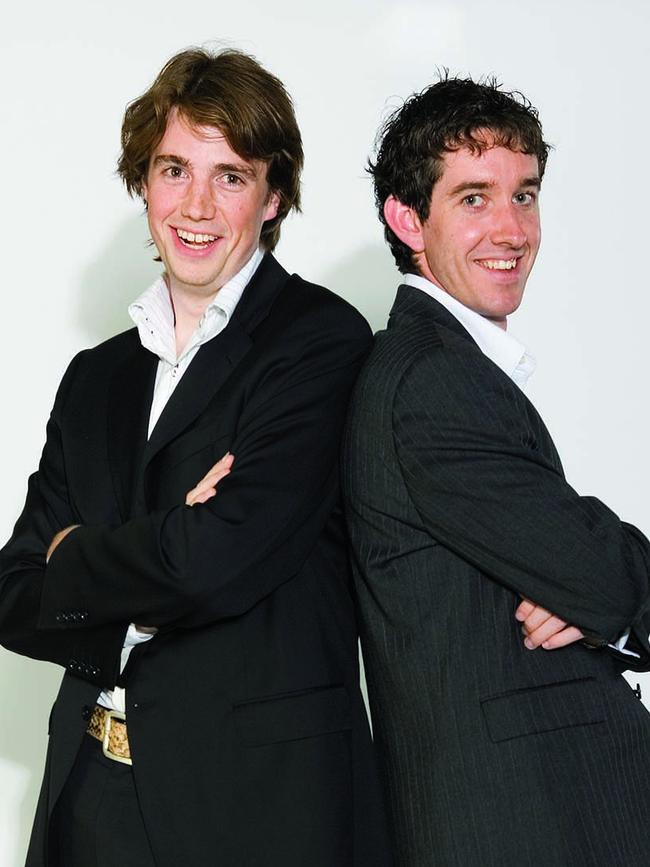

Atlassian’s founders: best mates, business partners and billionaires

The way the Atlassian co-founders marked their entry to the billionaires club says all you need to know about the start-up.

It was the end of a gruelling few weeks in December 2015 for long-time friends Mike Cannon-Brookes and Scott Farquhar. The two 36-year-olds from Sydney had been travelling around the US promoting their software company Atlassian to investors, culminating in its listing on the US stock exchange, NASDAQ, in New York. They had “rung the bell” at the exchange to mark the first day of trading — an event that included their excited families and work colleagues — and finished hours of media interviews in the US and Australia. By the end of the day they would be billionaires, their 13-year-old company worth a cool $8 billion.

Finding a break in their schedule, they walked up the hill from Times Square towards Central Park. You might think they would be on the lookout for a salubrious setting to celebrate their momentous achievement. Instead, keen to get out of the cold, they dropped into a pizza place. “We were there sitting in the back of this dodgy pizza place, eating pizza with oil and cheese dripping onto a paper plate,” recalls Farquhar, sitting in a modest conference room at Atlassian’s Sydney headquarters in his corporate uniform of jeans and T-shirt. “Here we were, on paper, we were billionaires and we were saying to each other, ‘Hey, which slice of pizza do you want? This was how we celebrated going public.”

Cannon-Brookes, the son of an English banker, who went to the upmarket Sydney private school Cranbrook, and Farquhar, from a working-class background in the western suburbs of Sydney, have known each other since they met at the University of NSW in their late teens about 20 years ago. They are best friends and business partners, working side-by-side for the past 16 years as co-founders of one of the most successful global companies to come out of Australia, worth more than $US14 billion and with an annual turnover of more than $US800 million.

Their project-tracking software products are sold to about 120,000 customers, including many Fortune 500 companies and some of the world’s big names: Spotify, BMW, Citigroup, eBay, Coca-Cola, Airbnb, Paypal, Sotheby’s and many of America’s top universities. NASA used Atlassian products to help plan the Curiosity rover’s mission to Mars. It used its Jira and Confluence software to help with project management as well as Fisheye, Clover and Bamboo to speed up computer coding. Elon Musk’s Tesla used Atlassian products to help develop the software behind his electric car.

Their partnership has lasted longer than The Beatles and many a marriage. Along the way they’ve been rocketed into Australia’s exclusive Rich Listers club before their 40th birthdays with an estimated combined wealth of $6 billion.

Those who work for Atlassian speak of the leadership of “MikeandScott”, the two names sliding effortlessly into one. “Our ‘marriage’, for want of a better word, works,” says Farquhar. “I don’t think either of us could have created what we created alone. We have incredible respect for each other’s perspectives. In some ways it’s like a normal marriage. It is all about respect for each other. If you believe you can do better by yourself, then you are not going to last long in a marriage.”

Born a month apart on opposite ends of the Earth, they started the business using $10,000 of credit card debt, coding through the night and going home when the sun came up. They were best men at each other’s weddings, have stood in for each other when one or the other took a career break, and have managed to work through a co-founder model that has more in common with US tech companies than Australian industry: think Hewlett-Packard (Bill Hewlett and Dave Packard), Microsoft (Bill Gates and Paul Allen), Apple (Steve Jobs and Steve Wozniak), Google (Sergey Brin and Larry Page), and Oracle (whose founders included Larry Ellison and Ed Oates).

The two are now emerging on a broader stage in Australia through a combination of their wealth, opinions and influence. Farquhar, who last year paid $70 million for John B. Fairfax’s run-down historic house in Sydney’s Point Piper, is a board member of Innovation and Science Australia, which produced a report earlier this year on the policies needed to drive Australia’s innovation future. Cannon-Brookes has an expanding property portfolio and is putting seed capital into the next generation of Australian start-ups. Last year he challenged Elon Musk on Twitter to use his solar storage batteries to help fix South Australia’s energy crisis. (Late last year, Musk installed the world’s biggest battery in South Australia.)

Their relationship reflects a new generation of entrepreneurs who value collaboration more than competition. Technology has enabled a new era of real-time co-operation that has shaped the mindset of modern workers who thrive in a workplace very different from the command-and-control workplace of their parents’ generation.

Several floors above an historic Westpac building in Sydney’s George Street, Atlassian’s headquarters is a hive of activity as jeans-wearing 20- and 30-somethings buzz about. The area where Farquhar and Cannon-Brookes work is open-plan and white-walled, with white desks and glass conference rooms. It’s devoid of traditional corporate posters and paraphernalia; pot plants and hanging vines are the only real decoration in a space that feels as if it was set up a week ago by a start-up that could soon be moving on.

With offices from Silicon Valley to the Philippines, Amsterdam to Bengaluru, India, a significant number of Atlassian’s 2500-plus staff are based overseas and most of its board and investors are in the US, meaning few Australians recognise the scope of this empire.

For a tech company to have two or more founders is quite normal, says Cannon-Brookes, his dark brown hair shoulder-length and minus his trademark baseball cap. “A lot of them can stay together for long enough to get the business started, but the rare thing is for both founders to be given the credit. One of the things we have always done well is to make it very clear that it is a two-person thing.” He insists the two have never had a serious falling out. “We are not really falling-out people,” he says. “We have different views at times but we seem to be very good at resolving them.”

“My general rule,” Farquhar jokes, “is that Mike should do all the work and I do all the interesting things.” If all else fails, he says, the two have an agreement on how to resolve their differences. “If we can’t solve anything, our original shareholder letter says we should go to mediation. But if it can’t be solved it is scissors, paper, rock. I have a huge incentive to solve it before that because I’ve lost every game of scissors, paper, rock that I have ever played.” They make it seem so easy.

Cannon-Brookes was born for a global life. Hisfather, Michael, was working as a banker for Citibank in New York when Mike was born in Connecticut in November 1979. When his father and mother Helen moved to Asia, he and his two older sisters went to school in Hong Kong for a while before going to boarding school in England. Michael Sr moved to Sydney in the mid-1980s to open a Citibank office in Australia when then treasurer Paul Keating was opening up the financial system to foreign banks. Young Michael bought his first computer using the Qantas Frequent Flyer points he’d clocked up flying between London and Sydney. When his parents decided to settle permanently in Sydney, he moved back with them, attending Cranbook School, while his sisters stayed in boarding school in England. He finished near the top of his class, winning a scholarship to the University of NSW’s prestigious business information technology course.

Farquhar grew up in western Sydney, where his mother worked at Target and then McDonald’s while his father worked at a service station. He badgered his parents to buy him a computer although he knew they couldn’t afford it; his father eventually relented and brought home an old Wang computer that never quite worked. He attended the selective James Ruse Agricultural High School and also scored a scholarship to the UNSW BIT course. After an entry process based on interviews as well as high scores, he joined a hand-picked group of about 35 highly talented people studying at the height of the dot.com boom.

Cannon-Brookes and his friend Niki Scevak were more interested in work than study. They set up a company called BookmarkBox that allowed users to manage and share their favourite computer bookmarks online. After it was sold to a US company they both worked for US research company Jupiter, covering emerging media and telecommunications. Scevak, who now runs venture-capital investment firm Blackbird Ventures, moved to New York to work for Jupiter, leaving Cannon-Brookes in Sydney keen to set up another venture.

By then studying part-time, Cannon-Brookes set up Atlassian, which started out providing IT support for a software company in Sweden. One story has it that Cannon-Brookes sent out emails to a number of university mates asking if they were bored studying and would like to join him in the company. Cannon-Brookes says he only remembers sending an email to Farquhar.

Either way, Farquhar answered the call and joined Atlassian, its name inspired by the giant bronze statue of Atlas in the courtyard of New York’s Rockefeller Centre. Their goals from the outset were simple: never work for anyone, never wear a suit to work and earn at least as much as the $48,500 a year Farquhar had been offered to join an accounting firm. “Our initial goal was to prove that we could make as much money as our friends were making in consulting. There was no more glamorous goal than that,” says Cannon-Brookes.

From their shared house in the inner Sydney suburb Glebe, their business evolved from technical consulting to software design. Before long there were eight software engineers writing code and someone handling administration. “We tried three different products in the early days and one worked, so we put more effort into that,” says Cannon-Brookes.

The one that took off was Jira, which was designed to help in project management and keep track of reported software bugs. They put the product online and soon found themselves with paying customers. With no physical barriers to selling software, the product was global from the start. One of their first customers was American Airlines, which spent more than $1000 without speaking to anyone at Atlassian. There was another customer from London and another from Stockholm. “We used a lot of online communities and interest groups to raise awareness [of the product] in the early days,” Cannon-Brookes says.

Their strategy was to keep the price low for small groups of users. Once they used it they liked it, and encouraged their bosses to buy it for larger teams. “We have always been big on making the software available to as many people as possible,” he says. “We want our software to be bought, not sold. We have always wanted to have very low prices and high volumes.”

They began to work with a growing list of clients, the products evolving to meet their needs. Their early bug-tracking software developed into a tool to help people writing software work together, track problems and manage complex projects. Teamwork was a big theme.

The company culture reflected their personal styles: a relaxed dress code, table-tennis games and Friday night get-togethers. But there were also some strict codes that shaped the culture. In one of their early offices, at The Corn Exchange on the edge of Sydney’s Darling Harbour, their philosophy was written in marker pen on the glass wall of the conference room: “Don’t #%@& the customer”, “Create useful products that people lust after” and “Open Company. No bullshit”.

By 2004, Atlassian had more than 1000 customers in the US, despite not having an office there until 2005. In 2006, with more than 4300 customers and 50 staff, they were stunned to win the Ernst & Young Entrepreneur of the Year award in Australia.

They began to expand their US team, in 2008 making a key hire of American Jay Simons. By this time the word about Jira and other Atlassian products was getting around the tech community in California. Simons had worked for a software company in California and had first heard about Jira in 2004 from enthusiastic customers in the tech business. “What attracted me to Atlassian was knowing they had done one thing right — build a great product which was desirable and worked,” Simons says from his office in San Francisco. The next step was to meet the founders, who flew to California to see him.

“When I had my first meeting with Mike and Scott it was clear they were both very bright,” he says. “I was attracted to working with them as individuals. It felt like a bonus to have two founders who were so intimately engaged in the business, who were both so smart and ambitious. Instead of having one super-smart founder and chief executive, I would have the opportunity to work with two.” Simons joined as vice president of sales and marketing. He has worked for them ever since and now holds the title of president.

The evidence that this was a thoroughly modern workplace came in 2009-10 when the two founders, who each turned 30 at the end of the year, both got married — Cannon-Brookes to Annie Todd, an American woman he met in a Qantas lounge during one of his many trips between Sydney and San Francisco, and Farquhar to investment banker Kim Jackson, who had worked at Citibank and then Hastings Funds Management. Both took several months off from the business to go travelling. It was a chance to take a break from the company they had spent so much time building and also for each to gain the experience of running the company on their own. “There was a period in 2009 and 2010 when we both turned 30 and got married and went on our honeymoons,” recalls Cannon-Brookes. “We both took significant chunks of time off while the other person ran the business. At the time we had a few hundred people and a turnover of around $50 million. It was a big effort to run the whole thing and it gave each of us a flavour of the sole job.”

But it was also a time when the two faced one of their biggest ever crises. Farquhar was on his honeymoon in Botswana in 2010 when he received a message to call Mike. He needed him back urgently: the company was under siege from a hacker. Having found Atlassian’s weak spot, the hacker was causing serious problems, including messing with the company website. It was a full-on cyber attack by an unknown enemy. Farquhar and his bride had to get a car ride through the Kalahari desert and two light planes back to South Africa before boarding a flight to Sydney. He arrived to find Cannon-Brookes “just about expiring”. They shut down all but the most urgent operations, hired rooms in a nearby hotel and had staff working around the clock for five days straight until they regained control of the situation.

The incident showed how well the Atlassian team can work together. “He’s awesome in a crisis,” Cannon-Brookes says of Farquhar. “When things don’t go well,” adds Farquhar, “when you have security incidents or good people leave [four employees have died of cancer], to have someone there with you through that entire journey is really good.”

By this time the success of their product with US tech companies had begun to attract the attention of venture-capital investors. American Rich Wong, a partner in San Francisco-based venture-capital firm Accel Partners, recalls how he pursued the company. “Back around 2006 to 2007, Atlassian started to emerge as one of those unique companies,” Wong says. “It was the clear category winner in its space.”

In 2009 Wong began his “pursuit”, as he calls it, of Atlassian in earnest, flying to Sydney to meet Cannon-Brookes and Farquhar. Unlike many start-ups, the two had carefully managed their growth and were not looking for outside investors. “The company was always profitable, always generating cash, so it had no need for outside investors,” says Wong. “We had a lot of coffees and cocktails and dinners, trying to build a relationship with Mike and Scott, trying to convince them to let us become part of Atlassian.”

By this time Atlassian had 225 employees, a $60 million a year turnover and more than 20,000 customers, including Facebook, Cisco, Adobe, Microsoft, Oracle, Nokia, AT&T and Amazon. Most are still customers.

In 2010, not long after the security crisis, Accel invested $US60 million into Atlassian, valuing it at $US400 million. Wong joined the board and continues to serve as a director, providing valuable connections in the Californian tech community. The move made it almost inevitable the company would seek a stock market listing in the US, the world’s biggest market for tech stocks.

The two founders began recruiting some high-powered talent for their board, astutely reaching out to some experienced Silicon Valley executives. In 2012, US software entrepreneur Doug Burgum got a phone call from Farquhar. “We’re looking for a board member who started with something really small and stayed with it until it reached a multi-billion-dollar scale,” Farquhar said in a conversation recalled by Burgum in a Forbes magazine article last year. Not only was the Australian asking him to join the Atlassian board, he wanted him to become chairman.

Burgum initially demurred but agreed to take the job after flying to San Francisco to meet the pair. Lining up a high-profile chairman was a key plank in their plans for a successful listing that would depend on the support of US tech investors. When the listing finally happened in December 2015, those who had come along on the Atlassian journey including Wong, Simons and Burgum and Atlassian staffers found themselves considerably enriched.

Burgum stood down as chairman in 2016 when he decided to run for governor in North Dakota, a role he still has today; Forbes described him last year as “America’s best entrepreneurial governor”. Farquhar took over the role of chairman until handing it over to another impressive US-based executive, Shona Brown, a Rhodes scholar at Oxford University with a PhD in industrial engineering and industrial management from Stanford. She worked as an executive with Google from 2003 to 2015 and is a former partner with consulting firm McKinsey.

Atlassian continues to grow. Its stock market valuation is now more than $US14 billion — more than twice as much as when it listed two and a half years ago. And the demands of running a global US-listed software giant have seen the roles of each of the founders become more defined.

Cannon-Brookes says they are each running about half the business. “We are quite delineated in what we run. Scott tends to have the technical products as well as finance, legal, IT and human resources. The front-end stuff such as marketing, customer support, sales and design tends to report to me. But it’s not like there’s a wall. There are lots of meetings where we both have lots of opinions on both sides. It is constructive and healthy if it is done the right way.”

Working near each other in their Sydney HQ, in which neither has a specific office, Cannon-Brookes says they are both aware of the potential pitfalls of the co-founder, co-CEO model. “We try very hard to avoid the multi-parent syndrome [where people go from one to the other to get a favourable decision],” he says. Their partnership works because while they share a similar world view, they bring different strengths to the business. “There is enough overlap to be congruent but not entirely overlapping to be redundant,” Cannon-Brookes says. “When you have a co-founder model, you need alignment otherwise there will be too much friction. But if the skills are exactly the same, you often find it can end up being a source of tension.”

In the 10 years since his initial meeting, Atlassian president Jay Simons has observed the working relationship between Cannon-Brookes and Farquhar at close quarters. “Mike and Scott are still the same,” he says. “They are always very grounded and down-to-earth. Mike has been wearing baseball caps and flip-flops for as long as I have known him. They still walk the halls and sit down and talk to everyone at lunch and meet the new hires.

“Mike is more of the dreamer. He is incredibly aspirational and ambitious. He is always thinking about a new mountain to climb. Scott is more operational. He will be thinking about the paths to get there. Mike is usually the one who is challenging the bigger, taller, harder-looking mountain. Scott will be thinking, how do we get from where we are to the top? They challenge both sides of your brain in different ways. It can be tiring, but also incredibly exhilarating. They both do a good job of asking ‘why?’ a lot. It is their super strength as both founders and CEOs.”

“Mike likes to be a contrarian,” says director Rich Wong. “He is a hypothesis-driven thinker. He sets a point on the horizon for us to get to or for the board to think about in a non-conventional way. Scott has that capability as well, but he tends to look at the entire system and think about how all the pieces interact and allow that vision or that point on the horizon to become a reality.”

Staffers say that when the two have different points of view, the discussion can appear quite heated. But each uses the debate to sharpen their thinking and test out ideas. “We disagree on stuff all the time,” says Farquhar. “But it’s usually, ‘Hang on, you are right and I am right. How do we put it together?’ There must be a different point of view or different ways of solving it. Having two people at the top means you can really call each other out on stuff. Sometimes I will say something that I think is really insightful and Mike will say: ‘Dude, that’s just wrong. I disagree completely.’ Your ego just wants to crawl into a ball and die, but you make better decisions because of it.”

The co-founder, co-chief executive model also allows them to “sub for each other”, as Farquhar puts it, allowing one to have time out when needed. Just after the listing in New York, he recalls, the two were planning a trip around their offices to celebrate the listing with their staff. “We were supposed to fly to Austin for lunch and then go to San Francisco for dinner and then fly to Sydney and then back again to the US,” he says. “We were standing at the front of the hotel on the way to the airport and Mike said, ‘I just can’t come. I am too tired. I need to sleep for a couple of days.’ I said, ‘OK. I’ve got it. Go back to bed’.” For the pair, teamwork beats going it alone any day. (TEAM is also the company’s US stock exchange ticker name.)

While they have come a long way, and are both fathers of young children (Cannon-Brookes has four and Farquhar has three), they insist they are young enough and determined enough to take the company to new heights. In January last year, Atlassian made its largest ever acquisition, spending $560 million on New York-based start-up Trello. With 19 million registered users, its website allows groups to work together to plan tasks and share documents. “It sounds strange but one of the interesting things about Atlassian is that we [now] have more ambition for it than ever,” says Cannon-Brookes.

Wong says Atlassian still has plenty of room to grow. “Despite all of the success of Atlassian being valued at what it is today, the founders are still chronologically quite young in their careers,” he points out. “There is still a very large market opportunity in front of this company. When the final story is ultimately written, we might still be in the first quarter of a long game. Mike and Scott have demonstrated that Silicon Valley is no longer a physical place. Great transformative companies can now be built from anywhere.”

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout