Artist Lindy Lee and her $14m sculpture, the national gallery’s most expensive work of art

News that our national gallery had commissioned artist Lindy Lee to create its most expensive ever work caught many by surprise. Why is her magnum opus so controversial?

Most mornings you’ll find her, the solo swimmer, plying the “laps only” lane of the Petria Thomas Swimming Pool in the little township of Mullumbimby, near Byron Bay. Here, in the shadow of the cone-like Mount Chincogan, she makes her daily pilgrimage, a ritual she replicates wherever she happens to be in the world.

She is the acclaimed artist Lindy Lee, 68, and this is her home pool, named after a local swimming legend and Olympic gold medallist. There is a small time-worn shrine to Thomas at the entrance to the pool. A wooden cabinet containing photocopied lists of her achievements and faded photographs of her in full flight in Olympic competition, all under glass.

But there’s something else going on here when Lindy Lee takes to the water. She is not swimming against a clock in this quaint country town pool, its immaculate grounds shaded by clutches of old palms. Here – over her regular 40 laps – she can be weightless, she can clear her mind and she can grapple with the ideas and notions that preoccupy her, not least of which are the small matters of life, death and eternity. “Yeah, so I’m immersed, I guess, so that’s it,” Lee says. “I can do other exercises, but it’s just not as fulfilling. It’s a meditation. It’s soothing… any fears or trepidations I might have get kind of burnt up during a swim, and that opens a space for literally retreat. My ideas come and float up. Everywhere I go, I swim.”

It’s arguable that 40 laps might not be enough to process her prodigious output. Her work – particularly her arresting public sculptures – are in demand and on display around the world. There is TheLife of Stars outside the Art Gallery of South Australia – a 6m-high, elongated mirror-polished stainless steel egg, reflecting the world and drawing you in to its intricate perforated surface patterns.

There is the intriguing brass form of The Garden of Cloud and Stone in Sydney’s Chinatown. Then there’s the eerily beautiful Secret World of a Starlight Ember that sits outside the Museum of Contemporary Art (MCA) at Circular Quay. By day it teems with the cityscape and nature it reflects, and by night it shimmers like some floating gift from outer space. Lee has said of the work: “[It] represents each and every one of us; the secret world is our secret lives in every moment that we exist… we ripple out into the world and the world ripples into us… that’s the dynamism of life.”

In 2019 she won an international competition to create a public work for New York City’s Chinatown, and made an ethereal 20m-high steel monument, Drum Tower. Since October 2020 her biggest solo exhibition – Lindy Lee: Moon in a Dew Drop – has been touring Australia. It will end in Western Australia this July.

Liz Ann Macgregor, former director of the MCA, says Lee’s work belongs to our age. “Lindy Lee’s work is especially pertinent today, as society is challenged by the realisation of the extent of the climate crisis, the impact of the Covid-19 pandemic which separates rather than connects people, the rise of populist policies that foster racism, and the Black Lives Matter movement,” Macgregor reflects. “Lee’s work is essentially concerned with the direct and intimate connection between humans and the universe, as a consequence of her exploration of her own identity, living between two cultures and her study of Zen Buddhism.”

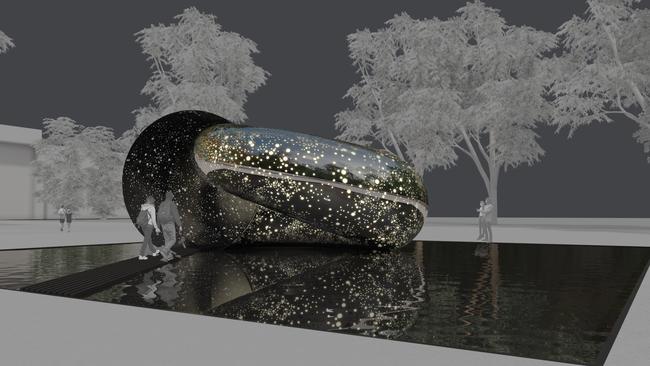

Now, the Mount Chincogan of Lee’s oeuvre. Ouroboros. A 13-tonne, 4m-high sculpture of recycled metal commissioned for the National Gallery of Australia in Canberra at a cost of $14 million and due to be installed by 2024. It is the NGA’s most expensive commission.

Yet before this spiritual and peaceful artist has even cast the first portion of her masterpiece, she has become a lightning rod in a rowdy debate over the cost of the work, its long-term value, and the NGA’s apparent lavish spending of public money in the midst of a pandemic that has laid waste to gallery crowds. Critics have even jumped on the artist’s impressions of Ouroboros, with one describing it as resembling “a large sliced bagel”.

And to think, the idea for this already polarising monolith, to be viewed and experienced by future generations, bobbed up here, at Mullumbimby’s humble local pool, with historic swimming caps withering in stale cabinets, and an urgent handwritten sign at the back of the canteen reminding staff to “do up bread roll packets”.

When you enter Lindy Lee’s home at pretty Coorabell in the Byron Bay hinterland, it’s like wading into a fast-flowing stream. There is life and movement everywhere. Young men and women – her artistic team – tidying rooms, carting in bags of groceries, ferrying material to the artist’s studio a short walk from the house. There’s Zoe and Timmy and Georgie. There are questions and answers and problems solved.

Lee’s Scottish terriers – Mae, Ziva, Mungo and Frank – are underfoot, gliding about the place at low level like freewheeling mops. “The swirl of life,” Lee says. She shared this home with her husband, photographer Robert Scott-Mitchell, until his death last year; he, too, was integral to Team Lee. Her life here in the rainforest is a long way from her childhood in Brisbane. Her parents had emigrated from China after the war and started a new life in the Queensland capital.

Lee was the only Chinese girl in her primary school at Kangaroo Point, and one of only two in high school, and she has vivid memories of chronic racism. Her formative years coincided with the start of three decades of conservative rule ending with Joh Bjelke-Petersen. “I think it’s not just me; anybody who grows up with any kind of difference is going to feel that painfully,” she says. “The White Australia Policy didn’t end until I was 20. That is a very significant thing to have in your background as a way of understanding yourself, you know, as you look through those filters. So growing up was painful. But things change.” She once described herself as feeling like “a fraud… a copy, and a flawed one at that… I was counterfeit white and counterfeit Chinese.”

Lee says a by-product of that early alienation was teaching her to collaborate to get things done. “You have to negotiate,” she says. “The reason that I enjoy working collaboratively is because you have to navigate different things in order to come together. That’s a great thing. So I’ve got a team… I direct them, but I think they’ll agree I’m always listening to whatever their suggestions are. You have to leave your ego at the door. I had to learn to listen and negotiate from a very early age.”

She initially studied to be a high school teacher but changed tack, later attending the Chelsea College of Arts in London and the Sydney College of the Arts. Her parents could not understand her desire to be an artist. “And why would they?” she says. “They were migrants. They were coming from an impoverished, World War II background out of China, you know?”

Like so many before and after her, she left Queensland to escape the oppressive Bjelke-Petersen regime. “I just had to leave,” Lee recalls. “You know, it’s changed incredibly now, but there just had to be more to life. Masses of people left because we were being suffocated. For an aspiring artist… there wasn’t a lot.”

In the late 1980s she embarked on a personal examination of her family heritage through a series of copied family photos from the 1950s and ’60s. She manipulated and burnt holes in the images. She says of that work: “Juxtaposing the images and burning the holes was a kind of recognition of the turmoil and lack of belonging: that sentiment ran very strongly through my family.”

She and Rob settled in Sydney, where Lee taught at the University of Sydney. Then, around 2015, serendipity worked its magic. “I lived in Sydney for 35 years and Rob and I would drive up to Brisbane every year to see Mum for Christmas, and we would come here [Coorabell] to stay along the way.” When the property came up for sale they bought it. “I got a redundancy that became the deposit. And somehow we made it work.”

In Lee’s studio, a short walk down a steep forest path, there are various works in progress. Paintings, templates for patterns to be burned or etched onto steel, prototypes for large public sculptures, and in the centre of the space a styrofoam ball that looks like a giant, skinned tennis ball.

Zoe Wesolowski, a graphic artist, is at work in the corner of the studio. Lee, her face framed by a sharp fringe, shifts her rapid-fire focus from one object to the next. There are glimmers of practical organisation in this space – a whiteboard, for example, on which lists and tasks are written – but it’s hard to grasp the artistic precision, the works of profound universality that emerge from this cluttered little space. That something so big can emerge from something so small.

“My work is concerned with the really intimate connection of the cosmos, OK, and by cosmos, what I mean is the length, depth and breadth of everything that has ever happened and will happen in the future,” she says. “It’s happening now. It’s the totality none of us can ever step outside of. So that’s what I mean by cosmos. It can be as mystical as you want or as pragmatic as the set of relationships that is your existence.

“We are actually at home right now here. This is whatever this is. This will never be more or less than ours. And sometimes that sense of intimacy with your existence gets lost because shit happens. That’s the importance of art. Great art keeps connecting us back to this deeper part of what we are, which we too easily forget.”

As a practising Zen Buddhist for the past 25 years, Lee talks about art and spirituality with logic and authenticity. She ruminates on stars and matter and the cycles of life without a hint of pretension. But in the end, it’s works such as Secret World of a Starlight Ember that do all the talking. These recent sculptures – big, bold and at certain times of the day and from certain angles capable of sending a shiver across your skin – elevate her into the top ranks of living Australian artists.

Now looms the elephant in the room. Ouroboros. Perhaps not the elephant in the room, but just the elephant. (At 13 tonnes, it will in fact weigh more than two African bush elephants combined.) Ouroboros, the ancient symbol depicting a dragon or serpent eating its own tail; it speaks of eternity, of endless return, the cycle of life, of time feeding back into itself, the never-ending story.

Her Ouroboros will be an immersive work that will invite people into its shell. That will glow like a beacon at night. A major work that has to go from Lee’s imagining and into the world as a real object. That may have to defy conventional engineering and come up with new, previously untried solutions. That, on the journey from the Byron hinterland to a foundry in Brisbane to the forecourt of the National Gallery in Canberra, may have to defy logic. And all the while the clock ticks down to 2024 and its official unveiling.

“One of my father’s favourite stories about stars isabout how, even when a star dies – you know, ‘That star died 100 million years ago, and we still receive that light, and somehow we’re blessed by that light’,” Lee says. “The Ouroboros… is a very ancient symbol that crosses culture and crosses the line here. No matter which country it is found in, its meaning is universal… the symbol of eternal return of cycles of birth and death. So here we’re dancing between something that is solid and something that is just drifting off to stardust.”

She clearly recalls the origin of the idea for the sculpture. During one of her swims she recalled some drawings she’d done with an Ouroboros. She loves the story, its transcultural theme traversing culture and millennia. “Pretty much, where there are snakes and there are humans, the humans make up stories about snakes, and that following his tail is universally meant for eternal return cycles and renewal. And that’s what I wanted – to express the hope for that.”

Lee’s move to large-scale public works was facilitated by a chance meeting with Daniel Tobin, one of the founders, with his brother Matthew, of UAP, a major public art and architectural design solutions company that had humble beginnings in the western suburbs of Brisbane in 1993 and now has offices all over the world, from New York to Riyadh. “They said, ‘Look, you should go and see our shed in Brisbane’,” Lee says. “I thought, ‘OK, the next time I’m in Brisbane to see Mum I’ll go and have a look.’ I’m thinking the shed is a double-car garage. It’s not. It’s like two aircraft hangars.

“So I arrive and they’re making massive works of art… They just said, ‘Come, we just want you to play, just come and play’. And I started to play and I started to experiment with some things with this technical assistance and I started to draw in metal then these evolved into these massive sculptures.”

UAP and Lindy will collaborate on Ouroboros. Daniel Tobin says Lee is fearless. “She’s not afraid of much and she’s prepared to take a risk,” he says. “Ouroboros will be a challenge for us in terms of making this work in a better way and using better methods. It will be 100 per cent recycled stainless steel. We’re adapting the business to reduce the carbon footprint of the work that we do. Ouroboros is a big part of that.”

At $14 million, Ouroboros will be the most expensive work of art in the NGA’s history. Its nearest rival is the 2010 “skyspace” installation Within without by American artist James Turrell, which cost $8.2 million. At the time of the announcement of Ouroboros, NGA director Nick Mitzevich, who commissioned the work, said: “In some ways it’s emblematic of the fact that the gallery has always been ambitious in what it’s done.”

Not everyone in the art world has been enthusiastic about the commission. The Australian’s art critic, Christopher Allen, wrote that the purchase was “another example of the poor quality of leadership in our most important art galleries, where fashion, money, virtue-signalling and populism all seem to take precedence over the core priorities of developing, caring for and displaying a great art collection.” He said Lee was a “respectable Australian artist” but the price was excessive for hers or anyone else’s work. “So why exactly does this one have to be so big and so expensive?” Allen wrote. “Because it is conceived as a so-called immersive work, which in this case means visitors can walk inside it. Immersive works have become popular in recent years because they offer a passive experience to audiences who are unwilling or unable to engage more actively with works of art.”

Sydney Morning Herald art critic John McDonald – he of the sliced bagel assessment – wrote that “the escalation in cost is breathtaking, considering the financial struggles the NGA has endured of late, first with the bushfires, then the pandemic. Visitation and revenue have collapsed, with the only respite coming from better-than-expected attendance figures for the travelling exhibition Botticelli to Van Gogh”.

He and other critics have measured the commission against the nation’s most famous purchase – Jackson Pollock’s Blue Poles, acquired by the Whitlam government in 1973 for a world record $1.3 million. (It’s now worth more than $300 million.) McDonald added in his critique late last year: “As it’s unfair to judge a work of art until it can be seen with the naked eye, it’s possible the proposed sculpture will be a masterpiece for the ages. But one anticipates another version of a successful formula, with a bit of razzle-dazzle after dark.”

NGA director Nick Mitzevich believes the imbroglio will dissipate and time will be the ultimate judge. “Well, I think the price is something that just polarises our audience, and I’m hoping over the course of the production of the work that that will become less important,” he says. “I always want to deliver value for money for the Australian public because we are working with both public and private funds. If you don’t consider the scale of the work… you know, the fact that there’s probably going to be 100 people working on it over the course of the next two and a half years, if you consider that it’s going to be 13 tonnes of finished stainless steel and that it’s sort of a sculpture and sort of an architectural feature, the price then makes sense. And so for me, it’s just important to make sure that the big picture is articulated over time and the value of it put into a context.”

Mitzevich says it is not reasonable to compare the purchase price of Ouroboros with something like Pollock’s Blue Poles. “It’s about both the scale of the work and technical complexity… whenever we commission, acquire or purchase a work for the National collection, we do that with the knowledge that we need to look after it for a minimum of 500 years,” he adds.

It’s a work that will be on display day and night, and Mitzevich notes that you won’t have to actually visit the gallery to enjoy it. “It has a democracy in that it lives in the public realm,” he says. “And so all of those things contribute to the cost of the work. And over time, I think that becomes less important. I’m confident about the validity of the idea and the technical and artistic merit of the work. It’s worth investing in Australian art. You have to be committed to its cost.”

Lee briefly describes, wide-eyed and almost childlike, how the NGA wanted her to think big, and how the actual cost of her vision kept creeping higher and higher. She’s unfazed by the critics and wants people to be patient.

“Hopefully I pull the rabbit out of the hat and it’s magic,” she says. “You know, as we went through the plans, the cost of it just kept going up, and I just kept freaking out because I was thinking this, this project is going to go south before it’s even properly drawn up. But Nick is a magician, and he just kept saying, ‘It’s not off the table yet’. He’s been wonderful.

“If it becomes as beautiful as I imagined it, then yeah, it’s going to be a hell of a beacon. For the gallery. For the country.”

So while the nation waits for Ouroboros, it might be instructive to go back to the Petria Thomas Swimming Pool and try to think like Lindy Lee, to get inside her vision, to see how she views the world. To go with her flow, let’s imagine this fenced oasis, not far from the junction of Mullumbimby and Saltwater Creeks and home to the Mr Wobbygong Swimming School, at night.

Forget the daily maelstrom of shrieking kids and young mothers seeking respite from Mullum’s humidity and the waft of fish and chips from the pool canteen. No, it’s nice to reflect on this place in the evening, when it’s locked and quiet, and the water of the pool gets to sleep after a day of turbulence.

What if, on a clear night, the great wash of stars across the Northern Rivers, untroubled by the light pulses of major capital cities, had thrown down their reflections onto the skin of the pool water? And what if the lone swimmer, setting off after dawn, had unknowingly absorbed some of those reflections in her imagination as she set off on her 40 laps? And she had caught some of that starlight in her hair and come up with a work of art for the ages? Amid all the critical yapping and pre-emptive judgment and howling and yowling about money, wouldn’t it be nice to think that?

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout