Artist David Hockney flourishes under lockdown in Normandy

Artist David Hockney is sitting out the pandemic in France, working relentlessly — and at 83, he’s happier than ever.

“I read in the newspapers,” David Hockney remarked to me last spring, “that longevity experts were saying something or other…” He paused for a moment, sitting in the sunshine of northern France, then added: “Longevity experts? Can you even be an expert on longevity at 45? Or do you need to be at least 80? I would think so.”

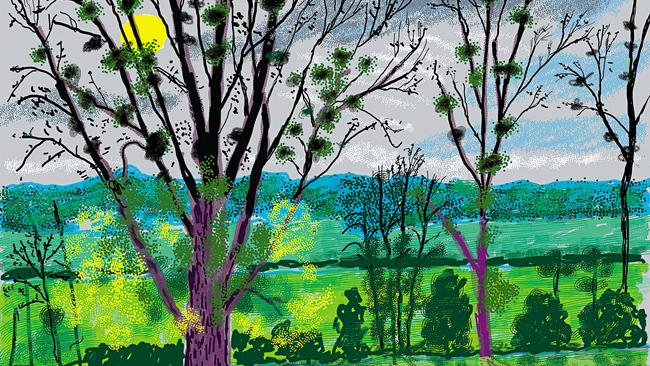

He was in the garden of the old farmhouse in Normandy where he has been living for the past two years; I was at home in England. We were chatting via FaceTime. In the last book we wrote together, A History of Pictures (2016), Hockney observed that in the future many people might end up living in a virtual world of visual images. But neither of us expected the process to occur so rapidly. Suddenly, due to the pandemic, half the population was working and conversing with friends and loved ones via Zoom or similar systems. Like millions of others, Hockney and I got into the habit of having virtual conversations, often around the cocktail hour, which eventually merged into our new book, Spring Cannot Be Cancelled. Its subject, you might say, is what David did next: his new life in the French countryside, where he began living in March 2019 and from where he has done an astonishing amount of marvellous work – paintings, drawings in pen and ink, animated films, iPad pictures and more.

Our conversations were about many other subjects, too: music, gardens, books, colour, rippling water, Hans Christian Andersen and Richard Wagner, OJ Simpson and Arnold Schoenberg, Monet and van Gogh, lockdown and current affairs. Another recurrent theme was passing time. On the day he was talking about longevity, Hockney was approaching his 83rd birthday, so by that measure he qualified as an authority on how to live in old age. After a puff on a cigarette and a sip from the glass of beer at his elbow, he continued his train of thought. “I think longevity is a by-product of a harmonious life. What makes for a harmonious life differs from person to person, but I think there must be some harmony in it if you live to be older: you find your own rhythm.”

Hockney’s own preferred way of life wouldn’t suit many other people. What he wants to do, all day and every day, is to paint and draw. He’s always been like that. Jack Hazan, director of A Bigger Splash, the 1973 film about Hockney, found he was “completely prolific as a painter, it was all he wanted to do. If you talked to him, after a couple of minutes he’d just drift away back to his studio and start painting again.” He could be describing Hockney now, nearly half a century later.

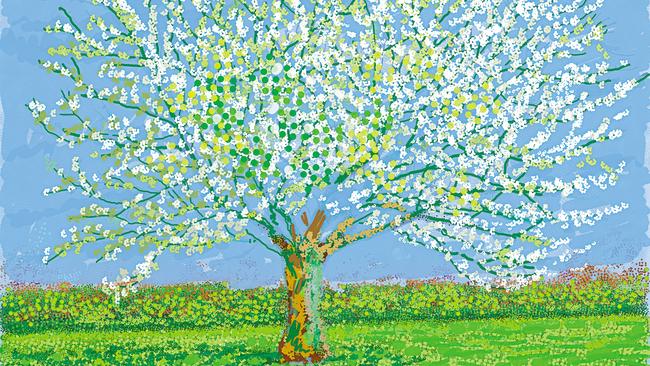

The discovery of his rural French retreatwas made by chance. He and his assistant Jean-Pierre Gonçalves de Lima (known as JP) took a short holiday in 2018, after Hockney’s stained-glass Queen’s Window in Westminster Abbey had been unveiled to celebrate the reign of Queen Elizabeth II. “We stayed at Honfleur for four nights, and then went on to Bagnoles-de-l’Orne. On the way there, I said to JP, ‘Maybe I could do the arrival of spring here, in Normandy.’ I could see that there’s a lot more blossom there. So I suggested that perhaps we should rent a house or something.

“The next day he rang some estate agents. We were on our way to Paris when he said we could see a house en route, just one. It was the only one we saw. It was called La Grande Cour. When we came in and saw the higgledy-piggledy building and that it had a treehouse in the grounds, I said, ‘Yes, OK – let’s buy it!’”

But, as Sigmund Freud argued, short of lightning strikes there is no such thing as an accident. So it was surely not entirely by chance that an artist long admiring of French painting and the Gallic way of life happened to find an ideal resting point just where and when he did. Normandy was the region where Claude Monet painted his garden at Giverny, and Monet, Hockney believes, lived the perfect life for an artist.

Hockney, with JP and his other assistant, Jonathan Wilkinson, and of course Hockney’s dog, Ruby, were happily settled in when I visited him in 2019. Certain routines had been established. Lunch every day, for example, was eaten at a small restaurant in the nearest town. (“It’s a workman’s café, really. For €14 we get a four-course meal. There’s tripe every day. I eat tripes à la mode de Caen, cooked in cider and Calvados, and andouillette, tripe sausages – I’m always eating them.)”

Of course, lockdown interfered with those lunches. But in most ways Hockney’s life altered much less than most people’s. Indeed, before the virus appeared he had already planned to lock himself down voluntarily. The idea was to stay within his circumscribed surroundings, to get to know a few familiar trees better and better, to see more and more in subjects he had already drawn and painted many times before. By April 2020 he was averaging more than one picture a day.

“I don’t even take a nap in the afternoon, because I get a lot of energy from work, a lot of energy. It’s gorgeous everywhere I look!” The lack of interruptions and visitors in the new, locked-down world was a positive bonus.

Such an existence would not suit many other people (perhaps scarcely any). But for Hockney, being confined to a small area of landscape and left in peace to depict what could be seen on and from it was a perfect life. Indeed, as he often observed, for him this was paradise. “In the Bible and other ancient texts, every important place is a garden. Where would you rather live? Where would you want to be? Even in Los Angeles, I am always drawing my garden.” But then he adds that most people wouldn’t notice the Garden of Eden if they were walking through it. They’d spend their time scanning the ground to make sure they didn’t trip over tree roots, he says. The world is very, very beautiful, but you’ve got to look hard and closely to notice that beauty.

Doing just that is something in which art and artists specialise. Painters may find interest in everyday details that almost anyone else would ignore as unimportant and ordinary, such as trees, flowers, rocks, pools, clouds, crockery, furniture and glassware (all subjects of recent Hockney pictures). He is a connoisseur of sights that many of us would scarcely bother to look at.

He described one evening’s entertainment last summer. “We had a stunning sunset. I could see it was going to be good because there were lots of high clouds and also open sky. The changing sky was fantastic! It was the most fabulous, luxurious light show, really. It went from being dark grey and white, then orange and red, and all the time the greys were changing. It was absolutely spectacular. Nothing could be a greater spectacle than that. I said, we were living in great luxury, being able to see this!”

Coming back to the topic of longevity, the reason why artists such as his hero Picasso may live a long time is “because when you are painting, you’re so involved you can get out of yourself”, he reckons. “What is stress? It’s worrying about something in the future. Art is now.”

There are, he muses, some advantages to old age. “You notice more with each successive year; I am doing that now. I can go in and look at things more closely, such as blossom. I took a branch and brought it in here to draw as a still life. It didn’t last long; I had to draw it in about four or five hours. It just rots when you bring it inside and lay it on a sheet of paper. It’s temporary, but then most things are.”

Spring Cannot be Cancelled: David Hockney in Normandy by Martin Gayford and David Hockney (Thames & Hudson $50, is out on Tuesday.

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout