Andre Agassi on Nick Kyrgios’ comeback, wife Steffi Graf, and the Laver Cup

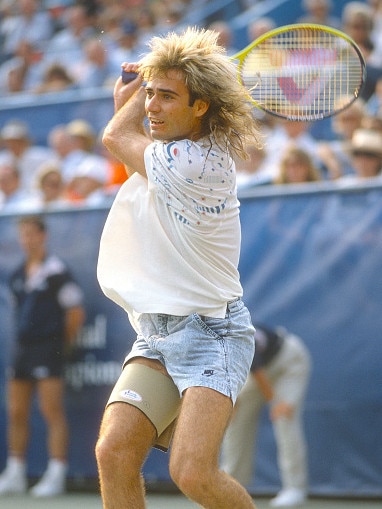

Andre Agassi was once a tennis bad boy who hated the game, with talent in buckets and a confrontational style. Sound familiar? As Nick Kyrgios plans his court comeback, this eight-time grand slam champion has some advice.

On the release of his 2009 autobiography Open, Andre Agassi called his father to acknowledge some of what was written and the twisted grip his words had started to gain in the media.

“The fact my Dad didn’t read was a problem, because the only thing he was going to hear was what people said. And that was sensationalised in a lot of ways,” Agassi tells The Weekend Australian Magazine. “So I rang him and said, ‘Dad, I just wanted to make sure, and hope, that you care about what I think about you. And I don’t want anybody else trying to frame that’.”

Agassi pulled the car he was driving to the side of the road, unsure what was to be unfurled by his father, a two-time Olympic boxer for Iran and a study in brutal ambition that led his son to simultaneously achieve global tennis dominance while holding a searing hatred for the sport.

If he had his time over, the old man told his son, he would eagerly change one thing.

“Dad said to me, ‘I wouldn’t let you play tennis. It would be golf or baseball – because you could play longer and make more money’.”

It’s an insight into the relationship between father and son that was laid bare in Open – an autobiography that proved much more than a tokenistic sales device and celebratory telling of the eight-time major winner’s life. Co-authored by JR Moehringer, the book remains one of the finest of its kind given the raw and surprisingly deep level of honesty presented across its pages.

It memorably outed Agassi’s use of crystal meth, and the wigs he glued to his receding hairline in the early years, such was the intense shame he felt in his balding.

Still, it was his father’s brutal and blinkered focus on sport that drew the attention of a public who came to feel a sense of sorrow for the tennis star and the childhood that was never his. Agassi had approached his father to be part of Open. “But he had no interest. He was like, ‘It’s your life – write what you want to write, you don’t need me…”

Emmanuel “Mike” Agassi died in September 2021. He was 90.

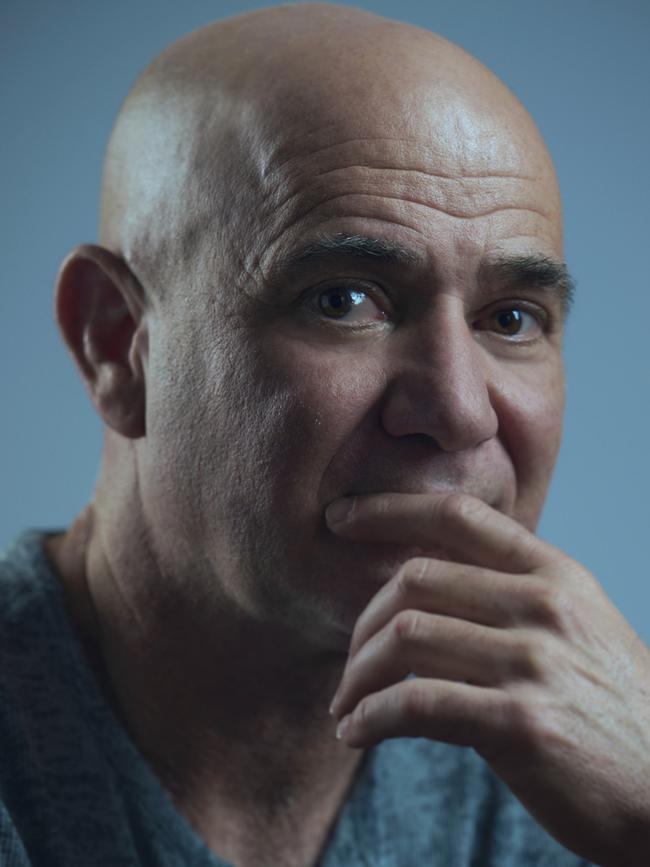

“There was no unfinished business,” Agassi, 54, says today, when asked of their relationship prior to his death. “I had the luxury of knowing he was proud of me and I had the clarity of realising how little that meant. The day I was able to speak to him and look at him as a person without the weight of him being my father – I could see where a lot of his brokenness came from.”

For the past 15 years, Agassi adds, no judgment was held. “There was understanding [between us]. It wasn’t about depth or growth, it was just a human-compassion relationship.”

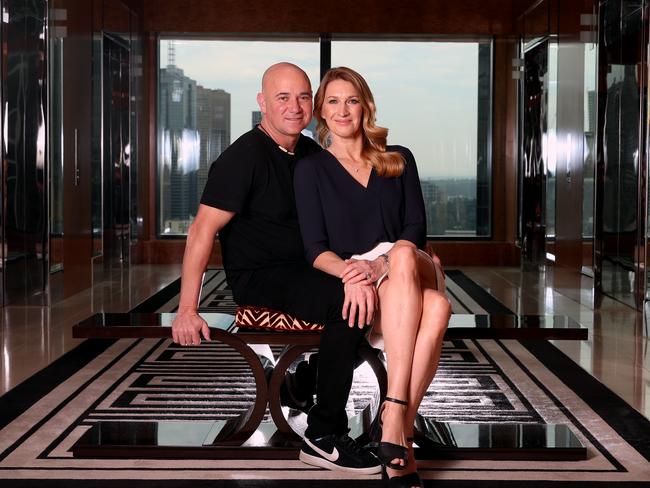

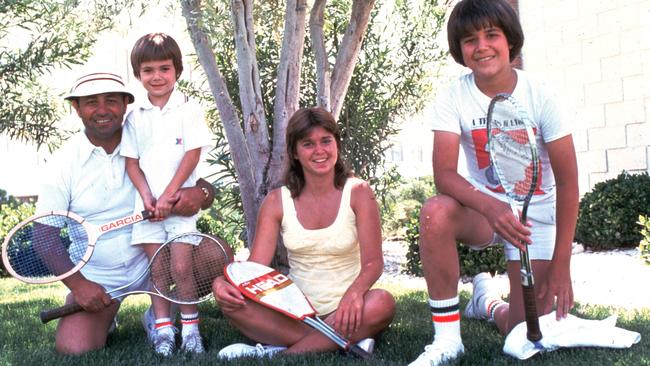

Agassi is a proud father, who, with his wife, the German tennis superstar Steffi Graf, is now watching on as children Jaden, 23, and Jaz, 21, start their amble into adult life. “A big thing for me was to give them what I never had – choice. We tell them, ‘This is your life, choose what you want and make sure your days reflect what you claim to be important to you.’ We hold them accountable and sure, it’s harder in application, but that’s been our North Star.”

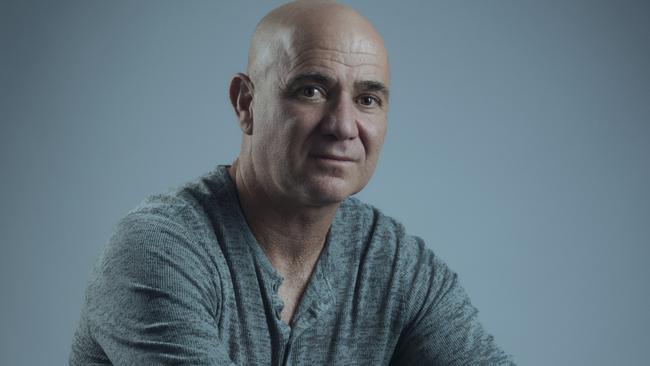

In conversation there is an intelligence and thoughtfulness attached to Agassi’s words; he often pauses to consider a response. He remains muscularly compact but his face is a little rounder and lined by time, and he moves with the tightened shuffle of an older man – which speaks of hips and a back battered by tennis’s violent, repetitive movements. Agassi gave the sport 20 professional years – joining the tour as a 16-year-old in 1986. He went on to dominate the ’90s opposite Pete Sampras, owned the world number one spot for 101 weeks and held aloft 60 trophies – Davis Cups, Wimbledon, the US and French Open among them, as well as an Olympic Gold Medal and four Australian Open titles.

He has long enjoyed Australia. And not just for the winning. “It’s a country that brings back incredible memories but also feelings of comfort and ease… And I have friends down here too, I like to get back and I feel connected here.”

Agassi’s visit to Australia last month, as part of a campaign for Swiss investment bank UBS, included being the headline act in a talk series at its Australasia conference. His appearance – in front of an auditorium of mostly male investment bankers – came less than a week after Donald Trump’s election victory.

A tennis player who read the game like few others in terms of space and depth and pace, Agassi the tactician also understands his position in wanting to propel the philanthropic work of his Andre Agassi Foundation. Politically he’s a registered independent – denying he’s been approached by either major party to show support. “I have to work both sides of the aisle to get my objectives accomplished with education, right?” he says. “I think, in this day and age, with megaphones and microphones and everybody having a platform, it’s easy to have the loud ones win the voices,” he says of Trump and the recent US election. “And it’s easy to feel like we’re more divided, but with difficulty comes opportunity – that’s what I’ve found in life. So, I root for our country and our country spoke clearly [in the 2024 election].”

His move into schooling – to educate marginalised children via the establishment of a scalable charter system – was driven by his own lack of education. It’s also about his desire to forge connections outside of tennis, which he first felt in the late ’90s, at a time when his ranking plummeted to a career-worst 141 and he was eyeing off early retirement. “I wanted to find a reason for playing and to find something that was bigger than me,” he says.

He caught a 60 Minutes story about the positive work being done through the publicly-funded and independently-run charter system. It piqued his interest and he set out to learn more. He then took out a $US40 million bank loan to build a debut school in an economically challenged area of his hometown of Las Vegas. “My lack of education played a significant part [in this work]. You know, tennis took my entire childhood – I had no choice. And then [I saw] these kids who also had no choice, because they didn’t have an equitable seat at the table as it relates to their education.”

Agassi has since crafted a “private sector solution” with the help of US investor Bobby Turner – their Turner-Agassi Charter School Facilities Fund has created 130 schools in marginalised areas across the US, educating close to 80,000 students daily.

“We need to understand that kids don’t fail us, we fail them,” he says.

Despite the chiselled aches of age, Agassi proves surprisingly nimble on the court. Albeit a shrunken pickleball court. It’s a newfound passion and he plays daily, often with Graf. This pushes a smile across your writer’s face – which is met with a sharp verbal volley. “Don’t you go laughing now,” he fires off. “Don’t worry, I won’t take that personally. And I do find that most people are like, ‘Why pickleball?’”

The answer has to do with fitness and the game’s accessibility, being easy to adopt at any age. There’s also the community it encourages. “It’s a low point of entry – anybody can do it and improve every 10 minutes. And you can bring your family in from, say, Germany ... everybody puts their phone down for two hours and plays. How good is that?”

Is it good for a marriage?

“Well, it’s either going to add to it or end it. I mean, we both challenge ourselves in an internal way when we play.”

Does he let Steffi win?

“I’m not stupid – we don’t play against each other,” he says.

Agassi points to the fact he and Graf become romantically entangled – marrying in 2001 – after he “got through a lot of things in life”.

“She’s smart,” he says with a laugh about the timing. “And she teaches me every day – I love and respect her and we’re happier now than we’ve ever been.”

Bending the conversation back to pickleball, Agassi says the game has become “a beautiful outlet” for both he and Graf – another reason he’s invested in its growth across technology and product. “I don’t necessarily think the professional side [of pickleball] is going to be the big thing, you know ... but the participation side – in five years from now it’s going to be all over down here [in Australia] too. I mean, I’m either going to be right or wrong, but I do know it’s added a great deal to my life.”

On a makeshift court in Sydney’s CBD as part of his UBS commitments, Agassi’s prowess and competitive spirit is on show as he plays with a stream of UBS executives and anointed clients. The mic’d up exhibition in front of 200 UBS employees, curious CBD workers and confused passing tourists is easy and fun. It’s obvious Agassi has played this PR game before – the banter, the gamesmanship, the easy shots to prompt a rally. Until, that is, he decides to end things with a show of power or placement from either side of his body.

After a few years laying low in the desert, Agassi is also making his return to full-sized tennis courts. Those close to him say he was, despite his matter-of-fact way and straightforward words, pained by his father’s passing. Of course he was. He rode things out in Nevada. Found pickleball. Leaned into family.

He also reconnected with former American tour mate Justin Gimelstob – who’s aiding Agassi’s return to tennis and its various aligned opportunities. Cue this year’s mulleted Australian Open campaign and some pressing of the flesh for Open director Craig Tiley. Cue his UBS engagement. So, too, the rumoured multi-million-dollar Apple TV deal for Open and the excitement that frames his replacement of John McEnroe as captain of Team World at next September’s Laver Cup.

Do we call it a comeback?

“That’s fair, yeah. I think the clearest way to categorise it is that I promised my wife two things. One, I’ll never be too busy, and two, I’ll never be too bored, because I’m dangerous in both scenarios.”

He denies his return to the sport has to do with reflection that often hits around life’s half-century mark. “I have the bandwidth now to turn my lens a little bit more towards the game that’s given me a pretty significant platform,” he explains. “And I wanted this past year to be where I can connect in a way that contributes and also adds to my own sense of enjoyment – I think there’s a real place for it now, in a real active way.”

Agassi admits to missing Rafael Nadal and Roger Federer. Still, he doesn’t see the game as poorer for the retirement of the two stars.

“I had the luxury of playing them a number of times, and watching what they brought to the game was incredible. But then it’s still this gladiator sport – the reason these arenas and facilities are growing is because there’s still human stories going on. And I enjoy the game on so many levels, from technical or strategic [angles], from just an appreciation of what guys are doing, what makes them the best, whether that’s now [Jannik] Sinner or [Carlos] Alcaraz.”

Does professional tennis need the unapologetic ways of the characterful Nick Kyrgios – a sentiment the 29-year-old Australian, who’s set to return from injury at the upcoming Brisbane International, has implied throughout his career?

“I don’t think tennis needs anybody,” Agassi says. “It’s a great platform to watch people push themselves and Nick is a hell of a talent… the sense I get listening to Nick is that he’s strong on what he feels – he’s clear at any moment and honest about what he feels. So that’s a good thing. But it doesn’t mean it’s always kind. You just hope with the platform, of being in the public eye, that it lifts people and the sport.”

Dare we suggest a return to coaching – as Agassi did with Novak Djokovic in 2017 – to help guide Kyrgios’s anticipated return?

“I’m a big fan of working with anybody that has a thirst for growth. So that’s not a question for me, that’s a question for how much growth somebody really, really wants.”

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout