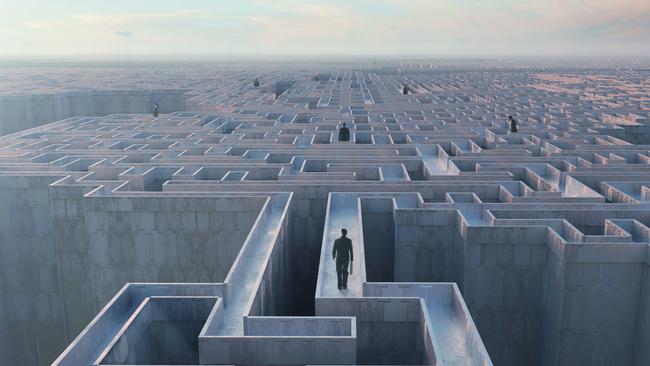

Among the truthers: into the fake news labyrinth

The middle-aged man in courtroom 11E is known as ‘Publisher X’. Fresh out of jail, he’s the anarchic face of 21st century news media.

Jake Sole is a 38-year-old fitness trainer from Sydney who practises yoga and Neigong meditation, drinks alcohol sparingly and avoids caffeine and red meat. He’s an advocate of animal rights and organic farming, and a keen proponent of holistic mind-body healing. He also believes that Hillary Clinton, the 2016 Democratic presidential election candidate, may have been involved in child trafficking. He’s convinced that fossil fuel companies are helping to block futuristic technologies that could supply endless free energy. He suspects the destruction of the World Trade Centre in New York, which killed nearly 3000 people in 2001, might have been a covert US government operation.

Sole has drawn these ideas from the internet’s vast network of alternative news and information outlets — from websites such as Top Secret Writers, YourNewsWire and Truth In Media, from YouTube channels hosted by “independent researchers” and blogs published by citizen journalists. Often the information comes to him unbidden, slotted into his Facebook newsfeed by automated software that has tracked and profiled his reading interests. Occasionally he will seek information out himself, pursuing an intriguing storyline into the labyrinth of hyperlinks that makes up the internet.

Rarely, if ever, does Jake Sole get his information from the mainstream media — the mass-market newspapers and television news bulletins that have shaped the public’s picture of the world for decades. “I’m not that interested in the contemporary narrative of what’s going on,” he says, sipping peppermint tea at a cafe near the gym where he works in central Sydney. “That’s not to say it’s not a useful thing; it’s just that I’m in a different place.”

A supremely fit-looking man with a shaved head and a cerebral demeanour, Sole believes mainstream news is beholden to government and corporate interests that suppress information the public is not “ready to hear”. Take the World Trade Centre attack: the mainstream view holds that Islamist militants flew two hijacked passenger aircraft into the twin towers, but the news sites that Sole frequents swirl with more sinister speculations about government-planted bombs and holograms beamed from space.

“The evidence I have read and listened to from pilots, engineers, demolition experts and firefighters who were on the scene, and the abundance of documents that are on the internet, if you look through all that you will find that a couple of planes heading into the towers is not going to demolish them,” Sole reasons. The 47-storey tower at 7 World Trade Centre, he points out, collapsed even though it was never hit by an aircraft; the official explanation that intense fire buckled its superstructure leaves him unimpressed. “I think quite clearly there is some skulduggery going on there. As to the reasons why, I’m not sure.”

Does he accept that two hijacked planes did actually crash into the twin towers? “Well, I’m uncertain,” he replies, “because I’ve looked into this and there are different ideas about what happened there, and how it happened. There wasn’t any wreckage of the planes recovered in the area. I don’t know, but maybe there is technology by which it could appear to take place. There is a suggestion that holograph technology was involved, and there is evidence that such technology does exist.”

The September 11 attacks were witnessed by thousands of horrified onlookers, filmed on scores of mobile telephones and video cameras and exhaustively analysed in a 10,000-page US government engineering report. Yet 17 years later, Jake Sole is one among millions of people who doubt it was an Islamist terror attack. A BBC survey in 2011 found that 15 per cent of Americans and 14 per cent of Britons think the US government of George W. Bush conspired to destroy the towers, a suspicion that appears to be growing: a 2015 poll by Vanity Fair magazine and CBS Television found that 24 per cent of Americans disbelieve their government’s explanation of the catastrophe. Other recent polls have shown that 29 per cent of Americans believe former president Obama is a Muslim, and 10 per cent are convinced that aircraft vapour-trails are toxic chemical clouds linked to climate change or mind control experiments.

To its early evangelists, the internet’s revolutionary potential lay in the free flow of information beyond the control of governments and corporate interests. “Information wants to be free” was the famous phrase coined by counterculture internet guru Stewart Brand in 1984. Today, billions of people are globally connected via Facebook, Instagram, Twitter and WhatsApp, a vast network that has become the principal portal on the world for people like Jake Sole. “I will often share information that I feel is the deeper truth,” he says. “New ideas need to get out there and be released among the public, to see what happens. If there’s a level of truth, there will be investigations.”

Some of the very people who helped create social media, however, are now expressing alarm about its uses and abuses in the wake of revelations about the spread of fabricated news and the influence of Russian internet operatives during the US presidential election. In November, former Facebook executive Chamath Palihapitiya admitted he now feels guilty about fostering a technology that is “ripping apart the social fabric” by spreading falsehoods and mistrust. Former Google strategist James Williams has warned that President Donald Trump symbolises the way politics is now infected by social media’s impulse to “sensationalise, bait and entertain”. The phrase “post-truth” has entered the lexicon to describe a world in which people no longer share a consensus view of reality. When anyone with a Facebook account can become a publisher with a global audience, how do we distinguish fact from fiction?

On the 11th floor of the Supreme Court building in Sydney, it’s easy to spot the man known to some judges as “The Publisher X ”. He’s the bespectacled middle-aged bloke in courtroom 11E, standing before Justice Lucy McCallum dressed in shorts, thongs and a white T-shirt emblazoned with the slogan Why Rent A Lawyer When You Can Buy a Judge? On this early May afternoon, Publisher X — whose identity, along with that of the “news” website he operates, is suppressed by the courts — is facing yet another defamation lawsuit, only a short time since he was released from prison after being convicted of contempt of court.

Since launching his website from his Sydney flat, Publisher X has published online hundreds of articles accusing lawyers, businessmen and senior government figures of involvement in corruption, bribes or paedophilia. It’s a body of writing notable for its almost total lack of supporting evidence; four women are currently suing him for alleging they conducted sexual affairs with a married executive, a case in which he memorably admitted to Justice McCallum that he had no direct evidence but would “try and get some”.

Today a food company is suing him for writing that its product is poisonous, but the hearing is adjourned because the judge has the flu. Publisher X won’t be absent from court for long, however: in coming weeks he’ll face a defamation claim brought by a prominent businessman, and he’s awaiting sentencing for contempt of court after refusing to remove certain articles — whose content is also suppressed — from his website. Last year he spent time in jail for the same offence, in the process losing his job and his rented flat, an experience that has not noticeably deterred him. “There are important issues here in relation to freedom of speech,” he insists.

Publisher X — whose website links to a Facebook page and Twitter feed, which also air his allegations — personifies the anarchic nature of 21st century news media. He describes himself on Twitter as a journalist and Facebook categorises his website as “news and media”, although in reality he is a former advertising salesman with no formal training as a reporter and little regard for old-fashioned notions of privacy, right of reply or fact-checking. His website named one prominent legal figure as a “known paedophile”, but when asked for evidence he replies simply that “everyone knows”. Judges have described his claims as baseless, offensive and “unsubstantiated rumour from unknown sources”, but he routinely defies their orders to take down articles, ignores suppression orders and refuses to pay fines. His website remains active because its servers are overseas, beyond the scope of court orders here.

Media historians have likened the news landscape of the 21st century to the pre-newspaper era, when the public gleaned its information from self-published pamphlets, town square gossip, satirical verse and Speakers’ Corner proselytisers. But no 17th century street-speaker ever enjoyed the global audience of Publisher X, who recently posted a Facebook item that reached nearly two million people. His website may have only 3823 followers, but they’re the kind of devotees who hail him as a free-speech hero and re-post his articles to thousands of their Facebook friends. Among those followers is Debra Shawcross, a Perth mother of three who has taken his example and started her own Facebook news page.

Shawcross recalls she began surfing alternative news sites in earnest four years ago while home-bound due to cancer treatment. “I wasn’t going out and getting newspapers,” she says. “That was something I used to do, but then I saw that information was at my fingertips.” On sites such as Neon Nettle, Breitbart News Network and The Unseen Encyclopedia she read about paedophile judges, about Democratic Party officials running a global child-trafficking racket, about aircraft “chemtrails” that are re-engineering the climate, and about the elite secret societies that control world events. “I’m nearly 50 and I had no idea about any of this,” she says. “It’s hard to take in; I just can’t fathom how corrupt it is.” Shawcross was so aghast she decided to join the “Truthers” and launch her own news blog on Facebook — Mum Always Said I Could Save The World. “I don’t want to show any disrespect to you, but the movement is called citizen journalism or reporting,” she says, adding that she now spends hours on the internet. “You look at one article, you get linked to others and before you know it you have spent hours online and you aren’t on the same subject that you started with. That happens to a lot of us — it’s called going down the rabbit hole.”

Like many people who are fascinated by conspiracy theories, Shawcross bristles at being called a conspiracy theorist. Still, it’s difficult to think of a phrase that better encapsulates the more outre ideas that swirl around the alter-news sites; many focus on 21st century fears such as paedophilia, climate change and Islamist terrorism, just as earlier generations fixated on the Kennedy assassination, Communism or the anti-Semitic tropes of a century ago. But information technology today allows such ideas to spread and cross-pollinate with a speed and reach that was previously unthinkable.

Public surveys increasingly show that faith in the media, government and business is plummeting, a phenomenon the global research firm Edelman has attributed to anxiety caused by chaotic world events and “a lack of objective facts and rational discourse”. “We’re looking at a world where truth is now thrown out the window and conspiracy is now seemingly the centre,” television producer Chris Carter said recently, discussing the return of his conspiracy series The X-Files.

We are now in the era of Pizzagate, the conspiracy theory that began as an anonymous rumour on an internet chat-site in 2016 and has since blossomed into an entire ecosystem within Facebook, Reddit and the alter-news sites. This phantasmagorical tale proposes that Hillary Clinton and her senior advisers were involved in a child-trafficking network operated out of American pizza restaurants, a claim for which no evidence has emerged beyond rumours of a ghastly video and elaborate speculation about the meaning of the word “pizza” in leaked Democratic Party emails. In October 2016, the internet’s pre-eminent conspiracy theorist, Alex Jones of Infowars, assured his millions of followers that Hillary Clinton had “chopped up and raped” children; a month later, 28-year-old Edgar Welch of North Carolina walked into the Comet Ping Pong pizzeria in Washington DC armed with a handgun and assault rifle, which he used to shoot the locks off a storeroom in an attempt to rescue the non-existent children.

Although Pizzagate was dismissed as fiction by the Washington DC Police Department and forensically debunked by The New York Times and Rolling Stone magazine, it lives on in the fertile greenhouse of online news sites. “Have you heard of Q?” Debra Shawcross asks, referring to an anonymous internet presence who has been predicting the imminent prosecution of Clinton campaign figures. “If you follow the Twitter links and have a look at that information, it’s all there,” she adds, naming Hollywood actors, occultists and politicians who are said to be implicated. “It’s huge — you sound like a crazy person. But when you’ve done the research it becomes like a pie chart; you can break it down into these little sections.”

Jake Sole, too, finds nothing incredible about the idea that Hillary Clinton and her circle engaged in child-trafficking. “No, I believe they’re under investigation for this right now,” he replies. “And again, I could be wrong, perhaps that’s false news. But it appears to be the case, so why don’t we see what the outcome of that is?” Hollywood producer Harvey Weinstein, he points out, is accused of assaulting and raping women with impunity for years, hiring former Israeli intelligence agents to help him hide his crimes. Who would have thought that was possible?

Sole’s reference to “false news” and the Weinstein scandal suggests how radically technology has changed the public’s perception of once-trusted institutions. News and information is today a 24-hour onslaught, delivering revelations that once would have strained credulity. At a time when Cardinal George Pell is facing historical sex offence charges, when mainstream entertainers such as Jimmy Savile and Bill Cosby are revealed to be sexual predators and a Royal Commission informs us that 4000 Australian institutions were implicated in child abuse, why should a child-sex ring in the Democratic Party be unthinkable? When the US President retweets conspiracy theories and lauds Infowars’ Alex Jones while routinely urging the public to ignore the “fake news” of the established media, where do people place their trust?

In the free-for-all of online news, old distinctions between Left and Right blur and pro-Green activists connect with Trump Truthers. The Australian Facebook page Infowars-oz pushes pro-gun, anti-Labor propaganda alongside warnings about the dangers of fluoride, vaccinations and mobile telephone radiation. Australian “investigative researcher” Neil Pascoe operates multiple websites promoting organic food, environmentalism and indigenous spirituality, while also denouncing sexualised art, “Freemason doctors”, global warming and the “Zionist spy program” hidden behind Facebook. The jet-streams from aircraft, Pascoe warns, are pumping carbon dioxide into the atmosphere to accelerate climate change as part of a United Nations “black-ops” program.

Sylvia Dardha, a mother of two who teaches meditation and Reiki energy healing in rural Victoria, follows Pascoe online and sometimes re-posts his missives. Dardha stopped reading newspapers and watching television three years ago in an effort to avoid advertising and focus on holistic health; today she doesn’t even listen to the radio while driving, drawing news instead from a grab-bag of alter-news outlets. On her Facebook feed, news items about veganism, anti-logging protests and Buddhist teachings appear alongside videos on the Illuminati, UFO sightings and demands to jail Hillary Clinton.

Dardha doesn’t necessarily believe all this stuff, she says, but she “enjoys the rabbit-hole” and likes to jolt people into a different way of looking at the world. For a while she delved too deeply into Infowars, with its nightmarish claims about the US Government orchestrating school shooting massacres and building desert concentration camps. She pulled back, noticing that friends who spend too long in the rabbit hole succumbed to a darkly cynical outlook. The internet, she says, has made it hard to have faith in any one story absolutely. “I think it’s an overload of information — like, what do you believe now, really? It was easy to believe one source, because if that’s all you’ve got, that’s all you’ve got. But with the internet, things have completely changed.”

Recently, Dardha shared a news item on Facebook that posited the Earth is flat, adding the comment: “Open your mind to the possibility?” When asked if she is really open to the idea of a flat Earth, she laughs sheepishly. “I think I am,” she replies, mentioning stories that circulate online about NASA scientists creating fake footage of outer space. She has spent time on the website of Santos Bonacci, an “astrotheologist” from Victoria who says images of a global Earth are an elaborate scientific scam. It occurred to Dardha that unless she can go into space herself, how can she dismiss such ideas? “You see these absolutely beautiful videos of space and what Earth looks like, but I can’t take it as an absolute truth just because we see it on YouTube. Once upon a time I would have, but I can’t.”

Kerry Stokes, chairman of Seven West Media, has discovered just how difficult it can be to rein in the wild free-for-all of online news. In 2014, Stokes sued an Australian website over a series of articles that a judge later described as baseless and scandalous. The case consumed four years of court time, during which the owner of the website defied court orders to take down the articles and made legal submissions that lacked legal standing or supporting evidence. Last month, Stokes was finally granted a permanent injunction against the offending articles — a largely meaningless victory given that they remain online and the court is powerless to shut down the website.

Stokes won’t comment directly on the case, which is believed to have cost him $200,000 in lawyers’ fees. But he says governments need to pass legislation that constrains sites such as Facebook from publishing “defamatory, inaccurate and sometimes dangerous material” with impunity. “There is a real flaw in the rules that makes it almost impossible for companies and individuals to take action to remove this material,” he says, “especially as many people are publishing this sort of material on overseas servers, which often brush aside complaints based on the belief that they are just a carriage provider and not the publisher. In addition, when action is taken in court there is no redress as the offending publishers often have no assets and therefore are not at risk for their damaging actions.” Stokes traces the problem to 1996, when the Clinton administration passed legislation stating that no provider or user of “an interactive computer service” should be defined as a publisher. As a result, Facebook blogs and Reddit forums operate outside most of the constraints imposed on traditional media by professional codes of conduct, government regulation, press councils or threats of legal penalty.

When Victorian police arrested Adrian Bayley for the murder and rape of Melbourne woman Jill Meagher in 2012, mainstream news outlets were forbidden from mentioning Bayley’s previous convictions for sexual assault because of sub-judice laws designed to guarantee accused criminals a fair trial. Meanwhile, Bayley’s brutal history circulated freely on the internet, notably on a Facebook page dedicated to denouncing him. Facebook declined to take it down despite the protests of Victorian premier Ted Baillieu, who suggested social media was potentially destabilising the legal system.

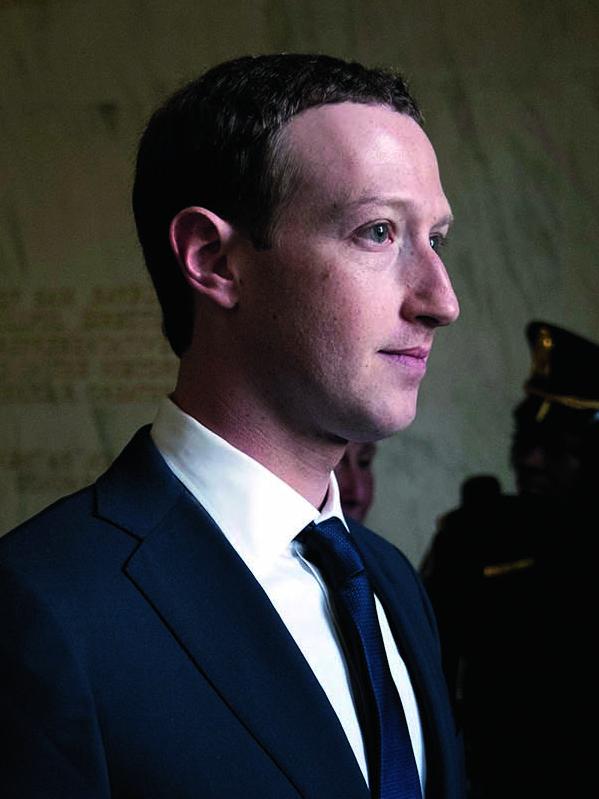

In April, the chief executive of Facebook, Mark Zuckerberg, appeared before a congressional committee in Washington and insisted once again that Facebook is a technology company rather than a publisher, a line that internet giants such as Google and Twitter have doggedly adhered to. It’s a stance that looks increasingly untenable in the wake of revelations that Russia may have influenced the British Brexit vote and the US presidential election by infecting millions of social media accounts with fabricated “news” items. Facebook has since deleted hundreds of Russian-planted accounts, and Zuckerberg conceded to Congress that the company is responsible for the content it distributes, making his business sound a lot like publishing.

Last month, six US families whose children were shot dead in the 2012 Sandy Hook Elementary School massacre launched a defamation action against Alex Jones of Infowars for claiming the shooting was staged. That case could put internet conspiracy mania on trial, but for mainstream media companies the problem remains that they play to a different set of rules than the alter-news sites, as the Bayley case in Victoria showed.

In February, The Daily Telegraph published a front-page story and photograph confirming that Vikki Campion, the 33-year-old former adviser to then National Party leader Barnaby Joyce, was pregnant with his child — a massive scoop in mainstream media terms, but no surprise to the many people who had already come across speculation and unconfirmed reports about Joyce circulating online. One independent news blogger had even travelled to Tamworth in November to report on “rumours” that Joyce was about to become a father for the fifth time, and not to his wife.

Such cases reinforce the suspicions of Truthers like Debra Shawcross that the real news is being hidden from view. “I will turn on the news and suss what they’re saying,” she says, “but what they’re telling me I have already heard a month ago or days ago, because news works so quickly now. I think we relied too much in the past on getting our newspaper, reading it and trusting it. Because we [bloggers] are personal, whereas you guys have to be factual. That’s a huge divide.”

Like many who follow the Pizzagate tale, Shawcross excitedly told her blog-followers early last month that earth-shaking proof of the Hillary Clinton child trafficking ring was about to be revealed, perhaps as soon as May 6. But May passed uneventfully, the episode a repetition of previous false predictions about imminent arrests or the release of damning videos. Shawcross wasn’t disillusioned, though — by early June there was talk of new revelations just around the corner. “No, I don’t lose faith,” she says. “Because I know that eventually the truth is revealed.”

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout