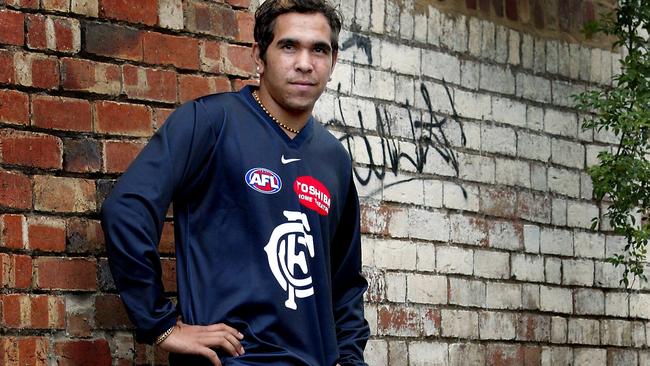

AFL star Eddie Betts: ‘Every time I see a message pop up on my social media I think, I hope it’s not racist’

Brilliant on the field, Carlton’s Eddie Betts is also one of the AFL’s most beloved stars. But behind the scenes, the racism is taking a toll.

The ball is kicked long into Adelaide’s forward pocket where Eddie Betts is lurking like a seagull on the hunt for a hot chip. It’s a full house at the Adelaide Oval, 2016, for what’s been, up until this point, a seesawing contest between the Crows and the GWS Giants. As the Sherrin descends from the night sky two Giants defenders leap for the ball and it ricochets towards the boundary. It looks like it will dribble over the line when Eddie swoops.

Time slows as he weighs up his limited options, his hand resting on the ball. He gathers it up, keeping the ball in play while his feet are out of bounds. He’s surrounded by two Giants, who have him mustered into a seemingly inescapable corner. But Eddie has them mesmerised – his eyes say one thing, his feet say another. He baulks right and jinks to the left. Like Winx, coming last and hemmed in on the rails as the field turns into the home straight, triumph at this moment seems both impossible and inevitable.

“Eddie,” says the commentator, “… fools ’em all.” He lunges free from the desperate clutches of a defender. “Escaped!” He’s at an acute angle. “Eddie Betts!” He doesn’t need to look where the posts are. “Eddie!” Running at full pelt he drops the ball to his boot from 35m out. “Eddie!” The ball goes high. The ball goes straight. The stadium erupts. “Eddie!” He puffs out his chest, grins and looks up briefly, instinctively, to where his family are in the stands – he never fails to find them in the crowd – before being pummelled by his teammates. “Eddie Betts!”

“Is that Goal of the Year?” Of course it was. It was the third time he’d won it, but he wasn’t done. Last year he did it again for the Crows against the Gold Coast with a left-foot snap, a banana kick from the boundary after plucking a fumbled ball from nowhere like a rabbit from a hat. “Oh Eddie Betts, you’re a magician!” What are the chances of someone scoring Goal of The Year four times? The prize has officially been up for grabs for 20 years and Eddie has won it 20 per cent of the time; he’s been runner-up a couple of times as well. What are the odds? There are hundreds of players who each year kick thousands of goals and yet one player has won four times. According to the geeks at Champion Data – taking into account the number of seasons Eddie’s played (16) – it’s 1 in 171,254. If he wins it again this year the numbers will be close to one in 10 million.

But then Eddie Betts is used to beating the odds. The odds are he should be in jail. Or worse. If your name is Eddie Betts, the odds are grim.

Betts’ path to anointment as “one of AFL’s greatest small forwards” was forged in the red dust of Kalgoorlie, Western Australia, and in the sandy backyards of the tuna town of Port Lincoln, South Australia. His dad’s mob, Wirangu and Kokatha people, came from around Ceduna, SA, while his mum’s side are Guburn people from the goldfields of WA. His parents split when he was a preschooler and he spent his childhood crisscrossing the Nullarbor.

Schooling for Eddie was patchy (he only learnt to read and write properly when he arrived at Carlton Football Club as a teenager) and so he filled his days solving problems of movement – how to scurry up a tree; how to dent a road sign with a rock from 40m; how to take down a cousin twice his size; how to thread a footy through posts at an acute angle with someone pulling at his shorts; how to slip through a hole in a fence to escape the cops.

“In Kalgoorlie the main house was my Pop’s house at number 12 Boomerang Crescent,” he says. “We just lived freely. My aunt lived around the corner and we used to wander from one house to the other all day, playing footy. I always had a ball in my hand.” But it was hardly a bucolic existence; his languid days of backyard footy and swimming at the pool were punctuated by death and violence and divorce, set against a backdrop of poverty, disease and jail. He dabbled with drugs and booze and petty crime.

“I vaguely remember going to visit Dad in jail,” he tells me. “I remember going in and seeing him and saying hello and he was dressed all in green.” He relays this in a matter-of-fact manner because this seemed normal; everyone had someone inside. His dad went away for a couple years for theft, and for domestic violence. His aunt shot his uncle in front of their kids. “My father, my aunt, my uncle… they all spent time in jail,” he explains. “I’ve been locked up in the cells before too. When white people get sent to jail it is a big deal.” Black people just grow up with it.

June 2020. Eddie Betts says he’s tired of all the abuse after a social media post depicts him as a monkey. “First week back and our Indigenous players are already being vilified,” said the AFL Players’ Association’s Paul Marsh. “They deserve to be able to go to work, play football and enjoy it like everyone else. This stuff is draining, personal and really hurtful.”

I am chatting with Eddie via Zoom and, due to these strange Covid times, he’s in a posh resort in Perth with his Carlton teammates “in the hub”, playing a bunch of games in WA before he’ll fly off to Brisbane to do the same. We are chatting about footy, family and life. He’s been in the news for calling out a racist incident – a social media post sent to him, which included a photo of a monkey. It came on the same weekend that AFL players took a knee before the start of their games to show their support for the global Black Lives Matter movement against racism. “If at any time anyone is wondering why we work so hard to bring attention to the importance of stamping out racism, this is it,” Betts wrote in response to the monkey photo. “It deeply hurts and you think to yourself, ‘Why do I keep playing footy if I keep copping this? But I want to make a change,” he later added.

In our Zoom call he’s remembering Kalgoorlie, where the police would regularly and randomly stop and search him and his cousins. He was arrested and placed in the cells one day, as an 11-year-old, after the police had rounded up a group of young black kids to run their details through a computer. They let him out a few hours later when they realised the outstanding warrant they’d arrested him for was for Edward Betts, his father. “I just thought it was normal that cops would hate us,” he says. “I thought that’s what cops did. Until I was older, I never thought: ‘Why?’”

It left him scarred. “The fear of the law is stuck deep within me,” he says, almost at a whisper and leaning in to his computer screen. “Whenever I drive towards a police officer I always say to my wife and kids, ‘Watch out! Cops up ahead’. Even though I’ve done nothing wrong – I’m driving a $100,000 car that I paid for myself – but I always look in the rear vision mirror to see if they’re doin’ a U-turn. My wife Anna, she tells me off for doin’ it, and I don’t want my kids to be scared of the law… but in my growin’ up was the fear of the law.”

It is not unfounded. Anna tells me that in Melbourne Eddie was pulled over so often, “six times a year, even more”, that they ended up making a complaint to the Office of Police Integrity. “It was just ridiculous,” she says. “They just kept pulling him over and asking for his licence.” And then there was an incident in 2006, not long after he won his first Goal of the Year in only his second season in the AFL, playing with Carlton. (It was an exquisite right-foot snap from the sideline that he snuck in while a brawl between the boofheads of Carlton and Collingwood was raging midfield.)

Betts was feeling good, driving around in the flash new Toyota Aurion he won for kicking that spectacular goal. He’d just been to Subway to get a sandwich and had pulled into a pub carpark to eat it. “I took one bite and next thing two cops pulled up in a car beside me,” he says. They ran to either side of his vehicle, dragged him out and put him up against a fence. He was terrified. “Who owns the car?” they shouted. “Me,” he said. “How did you get it?” they demanded. “I… I won it,” Betts stammered. “Bullshit!” One of them kept him pinned against the fence while the other checked on his details. Eventually, they handed him back his licence and drove off. Betts sat in his flash new car, frightened and feeling like shit.

“You know,” he says during our long, rambling conversation. “I am really passionate about black deaths in custody… about Black Lives Matter. You know my grandfather was one of the ones.”

Eddie’s grandfather, Edward Frederick Betts, was born on the Koonibba Mission, east of Ceduna, South Australia, on March 10, 1938. His great-grandfather, Robert Betts, had lived a traditional lifestyle until he and his family were herded into the Lutheran-run mission where grandpa Eddie would grow up. The children were, according to Koonibba’s pastor Carl Hoff, “the hope for the future… it is very difficult to gain old people for Christ.” The children would be “Christianised” and “Europeanised” at Koonibba.

Grandpa Eddie left the mission to find work hauling sacks of wheat in Ceduna, where he met his wife, Veda Miller – they would have six children together. He was a brilliant Australian rules footballer who won best and fairest in the Far West Association. Talent scouts would travel to watch him play. In 1963 he was courted by the Whyalla North Football Club, an offer that included a job at BHP. One day supporters of the rival Whyalla West Football Club got wind that the great Eddie Betts was coming to town; they hijacked the bus on the outskirts of Whyalla and convinced him to play for their club for more money and a better job at BHP. Eddie played for Whyalla West for a number of years before being enticed to Port Lincoln, where he was guaranteed work as a wheat lumper. “It is obvious to me,” said Aboriginal Deaths in Custody commissioner Elliott Johnston QC in his 1991 report, “that he became a very popular figure amongst football followers all over the West Coast for his ability and flair.”

Then Eddie developed health issues and had to retire. His work dried up. “His life appears to have gone downhill from that time onwards,” Johnston noted, citing his various convictions for drunkenness and domestic violence. Veda would often call the police when he got drunk and violent. “It was generally a happy household and despite the arguments he cared for me and my family very much,” Veda told the commission hearing. He tried for years to get off the grog – he went to Alcoholics Anonymous in Port Lincoln and to St Anthony’s Clinic, Adelaide. He’d be dry for months at a time but would relapse.

At 4am on October 6, 1987, Eddie Betts presented himself to Port Lincoln Hospital complaining of shakes and hallucinations. The doctor thought the 49-year-old was drunk but it appears he was suffering from a severe form of alcohol withdrawal. At 10.30am, in an agitated state, he discharged himself from hospital. His two daughters, Susanne and Sharron, became concerned when they found him lying on a couch in the lounge room, shaking and sweating. One of them called an ambulance to take him back to hospital. When he got there, around 12.15pm, nurses attempted to administer oxygen but couldn’t calm him down – he was hyperventilating and complaining of a “terrible pain in the guts”. The doctor was annoyed. He’d already treated him earlier in the day. In his notes he wrote: “Still drunk… he does nothing to help himself.” He ordered the nurses to call the police.

When the police arrived the doctor told them that Eddie was “putting on an act”, that there was nothing wrong with him and that his only problem was that he was drunk. The police were reluctant – they’d known Eddie for years and thought he seemed more agitated and restless than drunk. He was shaking and sweating and unable to stay still. Nonetheless they arrested him under the Public Intoxication Act and took him to the cells at Port Lincoln Police Station. He arrived at the station at 1pm. At 1.30pm a police officer checked on Eddie, who was groaning and holding his chest. Twenty minutes later, when the officer checked again, he was lying on his stomach. He was dead. The pain in his guts was a heart attack.

Eddie Betts Jr was just two years old when his grandfather, the toast “of the West Coast for his ability and flair”, died in a police cell in Port Lincoln. Just two years later and before young Eddie was in school his dad – Eddie Betts II, also an incredibly talented footballer – would be sentenced to jail. Some of the earliest memories he has of his dad are of him dressed in a prison green tracksuit.

Eddie Betts is one of the great small forwards tohave played AFL and yet when you talk to people who know him, his football skills are not how they define him. “He is just such a lovely, caring person,” says St Kilda coach Brett Ratten, who coached Betts in his first stint at Carlton. “He was great with his teammates and like a father figure to the younger Indigenous boys. Eddie was just a great guy to have around the footy club.”

Lyndall Down, a welfare officer with the Melbourne Storm, first met Betts when she was working for Carlton FC in 2008 and she’s become a close family friend. Over the years she has watched as Betts and his wife, Anna Scullie, have taken in young Indigenous kids who’ve moved to the city or from interstate to play footy. Earlier this year she phoned him to see if they’d take in another, Jack Bowen-Bowyer, a talented teenage rugby league player from Hope Vale, North Queensland, and nephew of the former Queensland fullback Matt Bowen. Eddie and Anna said “of course”, even though they have four young kids of their own. “Getting these kids staying with an Aboriginal family is massive,” Down tells me. “You’ve got a young Aboriginal kid who’s never left home and you are taking them out of their culture and community… putting them with an Aboriginal family makes a massive difference.” Not only will Eddie take them in and mentor them, he’ll spend hours each week driving them to training.

“He is easily one of the most loved athletes Adelaide has ever been home to,” says David Penberthy, The Australian’s SA correspondent. “People just adored him.” When he played for the Crows (2014-19), Betts had a weekly spot on Penberthy’s morning radio show during footy season and the pair became friends. “He just oozed joy, on and off the field,” says Penberthy. “He’d be about to kick a goal from some impossible angle and he’d pop his head over the fence and ask one of the fans, ‘Whaddya reckon, should I drop punt this or check-side it?’” He’d kick the goal and grin back at the fans.

In an era of corporatised sport and management babble he plays with joy and flair and answers questions with wit and honesty. Back in 2008, in the Indigenous round against Fremantle, Eddie was given the honour of tossing the coin for Carlton, a task usually performed by the team captain. He was interviewed on the sideline about this after the game. “You got your team started off the right way. You had the privilege of tossing the coin, and you won. How did all that come about?” the boundary observer asked. “He called tails,” replied Eddie, “And it come up heads.”

August 2016. A woman is exposed on social media throwing a banana at the Adelaide goalkicking star. “I don’t think anyone should doubt that it was a racist act,’’ said AFL boss Gillon McLachlan. “A banana being thrown at an indigenous man is unambiguously racist.”

“Eddie is so placid,” his wife says. “So open. So raw.” He sees the good in everyone and so the pain when he is racially vilified is immense. “He genuinely can’t understand how people can be so horrible,” says Penberthy. “I reckon he’s made a lot of people question their own ambivalence around racism because he’s been so honest about the emotional impact it has had on him.” Week after week, year after year he’s had to put up with it. “It’s a bit of a white person’s luxury to say, ‘Come on mate, roll with the punches,’” says Penberthy. “Ed’s view is that he just keeps getting punched, all the time.”

“It’s exhausting for him,” says Down. “I remember when the banana was thrown at him he called me and was utterly distraught. ‘I can’t believe this has happened. I can’t believe that someone would do it.’ Every time it happens he goes, ‘But why?’ There’s a beautiful innocence to Eddie but it means his heart is broken each and every time.” He was so distraught after the banana incident that he asked Down to fly from Melbourne to Adelaide for his next game and promised to pay for her ticket. “I walked into the change rooms afterwards and he just looked so tired,” she says. “He looked exhausted. I’ve never seen Ed look so tired and he saw me – this makes me teary just thinking about it – he just came over and hugged

me. He was crying and saying, ‘I can’t believe you came.’”

Anna says that as the white wife of a black man she has spent years witnessing the everyday racism against her husband. There’s the time he’d broken his jaw and went into a chemist with a script to get Endone for the pain and they said they didn’t have any. She went back to the same chemist and they gave her the drugs on his script. Security guards are forever following him in stores. He’s sponsored by Adidas and, just two years ago, he took a big load of almost-new gear to donate to the Salvation Army. Sorry, they said, we are not accepting donations today – but they did when Anna took the same clothes in on the same day. On trips to the US, she’ll breeze through Customs while he’ll invariably face a lengthy interrogation. The list is long. “Every day he experiences racism no matter what he does,” she says. “When he walks out that door he’s putting up a barrier, and I see it.”

“Every time I see a message pop up on my social media page I think, ‘I hope it’s not racist’,” Eddie says. “So much of it I just let slide. But it is always in the background. Growing up black you’ve always got to worry about when the next thing’s gonna occur.”

Betts says he will forever feel guilty for not doing more to support Sydney Swans player Adam Goodes when he was booed out of the game. “The thing I really hate people saying is, ‘Oh Ed, you handled it way better than Adam did.’ I am like, ‘Hang on a minute, what do you mean? Adam is the one who gave me the strength to stand up against racism. You should be on his side.’”

Anna tells me that when Eddie was in Adelaide he was sent a letter, through the club’s fan mail, calling him an “Abo Faggot”. It was just before the Indigenous round. He was scheduled to appear at a press conference to promote it and he wanted hold this letter up and say, ‘This is why we have the Indigenous round’. But that’s not what happened. “I remember sitting around a room with five white men and Eddie,” says Anna, “and them all deciding on how he would handle it.” The white men decided it was best that the Aboriginal man not talk about racism in the lead-up to the Indigenous round because it might cause too much controversy.

It is a decision they both regret. “You can’t tell a black man how he should respond to racism,” Anna says. “Now, two years on, I think he’d just go out and do what he thinks is right.” If he had his time again he too says he’d do it differently. “I’d say, ‘Don’t worry about trying to protect me beforehand’,” he says. “Support us when we do call this stuff out. To ignore it is to be part of the problem. To call it out is to be part of the solution.” He will spend the rest of his playing days calling it out.

Betts began his career with Carlton as a teenager in 2005 and he’s played more than 320 games. After six seasons with the Adelaide Crows he returned to Carlton for his twilight years. Eddie reckons he’s got a least another season left in him after this one. Anna says she’ll tell him if he’s getting too slow and it’s time to give it away. But, she says, he’s been playing some pretty good footy of late. “Last week he got tagged, which means that someone sat on him the whole game,” says Anna. “And I’m like, ‘Honey, you’re 33 and you’re being tagged again. You’re back in your prime’… He’s still got it.” And not just on the paddock, she jokes.

They have two boys – Lewis, seven, and Billy, five – and two-year-old twin daughters Maggie and Alice. All four children were the result of years of fertility treatment. They weren’t planning on having more. “Then the Covid lockdown,” Anna says with a laugh, and then a sigh. “And, bang! It’s like ‘Are you serious, number five!’ Like I said, he’s still got it.”

The baby is due at Christmas. Eddie adores his kids and missed them terribly, being away in the hub. “I’m not going to give him too much credit,” Anna says, “because I believe that men should have that role, but now that he’s away I’m like, ‘Oh my god, I didn’t realise how much he does’. ” She says when they first started dating she had to come to terms with the fact that family is at the core of his identity. His dad Eddie lives in Port Lincoln and his mum Cindy lives in Kalgoorlie, along with his two younger sisters. “It’s different because they’ve survived such intergenerational trauma and they’ve all survived it together,” she says.

While Eddie may have another season in him he’s preparing for life after footy. He’s been writing a series of children’s books, Eddie’s Lil’ Homies, with black characters. He’s working with companies and government departments on cultural awareness programs. When he retires he wants to use his profile to work at changing many of those things that were “normal” in the communities where he grew up. He wants a new normal for Aboriginal people. “I want to educate kids,” he says. “I want to encourage them to go to school and get an education. I want them to know that alcohol abuse, sexual violence in communities – that violence against women and children – is not OK. I want to change all that.

“All we want,” he says, “is for the rest of Australia to understand us and to acknowledge what has happened to us.”

He broke the family tradition by not naming his first son Eddie. “I played 300 AFL games. I don’t want him to feel the pressure that he has to live up to my name. I want him to be his own person.” But maybe, he says, one day one of his kids will name their son Eddie. Hopefully by then the odds on Eddie Betts will have shortened.

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout