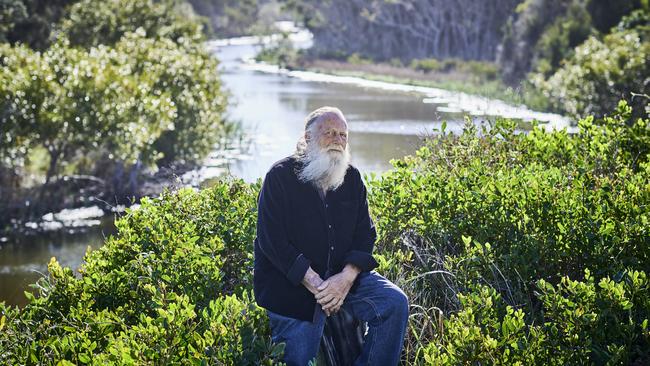

Actor, activist, philanthropist, scholar: the extraordinary life of Jack Thompson, 80

From poetry to Yolngu culture via Taoism, cinema and his own bare bum… a conversation with Jack Thompson is thoroughly enlightening.

His name is Robert. Robert the Robot. Square, serious, squat, about the size of a small refrigerator, Robert seems to enjoy his work and hums softly as he goes about it. It’s important work. Lacking true sentience, Robert has no idea just how important. But the people of Australia should collectively bow down and give thanks to the industrious little android, because Robert the Robot is keeping a living legend alive.

Thanks to the tireless work of his personal dialysis machine, Jack Thompson can drive a gunmetal grey Ford down from his oceanfront estate at Woolgoolga on the NSW mid north coast into nearby Coffs Harbour. He can alight briskly into a bright spring day, offer a broad grin, and proceed for more than three hours to deliver a virtually uninterrupted soliloquy about life as he sees it at 80.

It’s ostensibly an interview. But everyone knows Jack loves a chat, and it seems criminal to intrude upon the honeyed flow of his words, especially when the substance – vivid, whimsical, brimful of earned wisdom – transfixes as much as the style. “You just float on an ocean when Jack talks,” his Devil’s Playground co-star Don Hany once told me. “He’s just one with everything and everything is one with him. I’m like, ‘Just talk, man, just talk.’”

Some gentle encouragement here, a verbal nudge there, and Jack the thankfully-still-living legend keeps talking, his deep voice rising and falling with the soothing cadence of verse. He talks of fireworks and clowns. The surprising modesty of David Bowie. His love for Charlie Chaplin films and the essential nature of horses; the wisdom of Taoism and the enduring screen appeal of his own bare arse.

He recites swathes of poetry, word-perfect. Swoops in and out of accents and characters. He talks of communing with nature and mature-age love and the swifty he once pulled on Ita Buttrose, and there’s that cocky tilt of the chin that reminds you of the blue-eyed, tow-headed young actor who headlined the 1970s renaissance of Australian cinema.

He clears his throat and he’s 80 again. A ruddy-cheeked 80, with coin-bright eyes. “You look really well,” I tell him. “That’s the dialysis,” he says. He’d spent five hours the previous day tethered to his blood-filtering buddy, reanimating that famous Jack-the-lad twinkle. “Robert and I get on really well,” he says. “That really is what has given me back my health and vitality. It is an extraordinary machine.”

Thompson began dialysis after being diagnosed with end-stage renal failure in February 2018. He’d been feeling unwell for months but put it down to old age creeping up. By the time he checked himself into St Vincent’s Hospital in Sydney, his kidneys had failed and he was 48 hours from death’s door.

At one point, Leona King, his wife of 50 years, asked Thompson’s nephrologist if there was an alternative to dialysis. “The doctor said, ‘Well, you can have a dialysed Jack or you can have a dead Jack’,” Thompson recalls, pivoting to a high-pitched imitation of his wife’s reply: “Right, I think we’ll go with the dialysed one, don’t you darling?”

He’s on a short leash with Robert. But dialysis has set him free. In February, he was in Germany for the Berlin International Film Festival; before that, the Marrakech International Film Festival in Morocco. He shot two soon-to-be-released films around thrice-weekly dialysis sessions: the Adelaide-set comedy Never Too Late, and High Ground, shot in 40-degree heat amid the swamps and crocs of remote Arnhem Land. He considers the latter film, a confronting tale of indigenous resistance to white settlement, one of the most important of his five-decade career.

Having developed a deep kinship with the Yolngu people of north-east Arnhem Land, Thompson was formally adopted decades ago by the elders of the Gumatj clan. He remains an impassioned advocate for the preservation and veneration of one of the planet’s oldest living cultures. “It’s like the Great Library of Alexandria that was burnt to the ground,” he says. “It’s like finding that intact.”

Thompson launches into another poem, marvels at the “gentle and ephemeral” way indigenous people live upon the land, before turning his mind to “this Covid thing”. Could the pandemic be nature’s way of balancing the books? He switches gears, and now he’s making an elevator pitch for a gentle comedy set on a dialysis cruise. The islands of Vanuatu. A boatload of amorous cruisers, all hooked up to machines. “Love Boat on dialysis!”

The afternoon lengthens and we’re still here; one talking, one listening, rapt. Coffee goes unordered. Food uneaten. Bottled water unopened. Jack is in the zone and so am I. Just talk, man, I find myself whispering. Just keep on talking.

Thompson was nine years old when he stood before a group of strangers and shared with them what it was like to die.

I strove with none, for none was worth my strife:

Nature I loved and, next to nature, art

I warmed both hands before the fire of life

It sinks; and I am ready to depart.

“I knew what I was saying but it didn’t deeply affect me, if you know what I mean,” he says now of reciting Walter Savage Landor’s poem to visiting dignitaries at primary school in the late 1940s. “I was aware it was someone saying, ‘I’ve had a good life and I’m sort of ready to go’.”

The young Thompson grew up around poets and poetry, in the bohemian household of adoptive parents Pat, an author, and John Thompson, a writer and producer with ABC radio and an accomplished poet.

Born John Hadley Payne, Jack lost his birth mother at four. His father, a merchant seaman, was unable to care for him and he was sent to live at the Children’s Seaside Hotel, an eccentric establishment surely dreamt up by Tim Burton after too much Halloween candy. Located at Narrabeen on Sydney’s northern beaches, it was part orphanage, part boarding school, and understandably looms large in Thompson’s memory. “They would take children from broken families; practically every family was broken then, with the father at war and mother at work,” he says. Gita Campbell and Ireni Connell, “sort of breakaways from the education system”, were the two extraordinary women who ran it. “It was like The Old Woman Who Lived in the Shoe,” he says. “About 80 kids of varying degrees of competence in life. An extraordinary upbringing.” The school encouraged storytelling, singing and puppet-making; Thompson, aged six, would put on one-man plays modelled on the serials he watched at Saturday movie matinees.

Here’s Jack the wonder boy paddling down the river. What’s that? Oh no, a waterfall! Tune in tomorrow to find out what happens...

Peter Thompson, now a film critic, was a day student there, an only child. The two became inseparable. “We played the same games; we were in each other’s worlds,” Jack says. He ended up spending so much time at the Thompson home on holidays and weekends that they formally added him to the family. “Pat Thompson always said that I adopted them,” he laughs. Peter is currently writing John Thompson’s biography and Jack whiles away the tedium of dialysis proofreading each fresh chapter. “It’s great. It’s Dickensian,” he says, gathering wayward strands of beard into a tidy bunch beneath his chin. Shoulder-length hair and this wild Gandalf beard, initially grown out for a postponed, pre-Covid role, have been left to run riot. Smooth and gather. It’s almost hypnotic.

His adoptive father John stirred Jack’s lifelong connection with nature and indigenous culture, as well as his enduring love for bush balladeers such as Banjo Paterson. He recalls watching 8mm footage of a song cycle John Thompson recorded with the Yolngu people of Arnhem Land in 1949. Years later, aged 14, he found himself staring out the window of his Sydney Boys High classroom, daydreaming about “the world of those people in that film, out there in my own country”.

A friend of his father arranged work for him as a jackaroo on a cattle station in Central Australia, where he was the only white man working with the Alyawarre stockmen. “It was the best thing that ever happened to me in my life,” he says. “I saw a world that no longer exists really.”

Thompson catches glimpses, still, at the Garma Festival, held annually in north-east Arnhem Land to showcase Yolngu culture. He’s attended every year since 1999, when he came at the invitation of the late Yothu Yindi frontman and Indigenous rights activist Mandawuy Yunupingu, and spoke out against the Northern Territory government’s plan to scrap bilingual education.

“I received threats from [white] people: ‘Bloody actor, what would you know about the Territory?’” he says. But the Yolngu subsequently welcomed him into the complex system of clan and kinship that defines their world, the Gumatj clan giving him the name Gulkula after the sacred site overlooking the Gulf of Carpentaria where the festival is held. “I said to Mandawuy, ‘It’s a privilege, thank you, but I’m awake to you, mate. It’s a job too, isn’t it?’ And he said: ‘Well, yeah.’”

For Thompson, the job is this: “It’s to bear witness, in whatever way I can, to the fact that there is an Indigenous culture, a civilisation, that we need to recognise and communicate with,” he says. “Not out of kindness to them but out of respect for ourselves. If we don’t, we are missing out on the most extraordinary opportunity to examine what it is that human beings accumulate in 60,000 years of uninterrupted cultural continuum.”

In 2008, the actor established the Jack Thompson Foundation to support the Homelands Building Program, addressing unemployment and housing shortages in Arnhem Land. “In my lifetime I’ve seen the narrative shift,” he says. “I think we non-Indigenous people as a society have been nudged, pushed, dragged into a recognition of the denied reality of our interaction with these people.” He stares into the middle distance and recites a line from The Conqueror, a narrative poem his father penned in 1950:

Kangaroos more noble seemed

Held more humanity

Than these black, ruthless, kinless animals

Who shook their spears at me.

“That’s been there for long time, but I believe a shift is occurring,” he says. “It’s still got a long way to go, though; it’s so reluctant.”

Just 15 minutes into Never Too Late, a genial comedy set in a nursing home, audiences are treated to a screen-filling shot of Thompson’s bare bum. It’s a bit of a recurring theme in the actor’s work. 1975: Thompson as gun shearer Foley in Sunday Too Far Away, bum jiggling during a clothes-washing competition. 1994: director Geoff Burton cheekily recreates the scene for Thompson’s loving father to a gay son (Russell Crowe) in The Sum of Us. 2012: Thompson guest stars in the TV series Rake, playing an esteemed judge who enjoys going pantless. “They’ve written it in there!” he laughs, recalling how he read the Rake script. “‘Oh, Jack, we can get him to do this scene with no pants on.’ Then I get this script [for Never Too Late] and, oh shit, I’m going to have to drop my pants, show my arse again. All right. Why not? We can do that. Anyway, it’s a standard bit of slapstick comedy, pants falling down.”

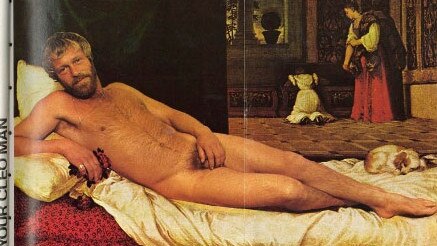

It was 1972 when Thompson first declared nudity no big deal by becoming Cleo magazine’s first male centrefold, a decision that catapulted him to sex symbol status overnight. When then-editor Ita Buttrose approached him, “it was like being asked, ‘Would you do a photo with a cat sitting on your head?’ Strange, but why not?” he recalls. “But I did insist I would only do it if we superimposed me naked on a classic nude painting. I wanted it known that nudity had been a focus in art for several centuries and that it had only recently, in a curiously puritan area of society, become associated with pornography.”

The Cleo team had other ideas. “They tried to get me to do a shot naked with the sun coming up between my legs on the beach,” he says, wincing. “But I knew a trick or two and arrived too late for the sun, very apologetic.”

The shoot was moved to a house in inner Sydney that he shared with actors including buddy Michael Caton. The resulting image of Thompson reclining on a red chaise longue in a pose modelled on Titian’s classic nude, Venus of Urbino, entered modern folklore. A bound copy now sits in the National Library of Australia.

“Gorgeous!” pronounces Jacki Weaver, who reteams with Thompson for Never Too Late nearly half a century on from their partnership in the lusty Seventies romp Petersen. “He’s much the same as he was in 1974, maybe slightly less active. He’s still handsome and he’s still adorable and he’s a terrific, really generous actor. Relaxed, but with a wonderful technique.”

Never Too Late centres on a romantic mission: a group of ageing Vietnam POWs, played by Thompson, James Cromwell, Dennis Waterman and Roy Billing, re-enact The Great Escape in breaking out of a retirement home to rescue an Alzheimer’s-stricken damsel (Weaver). Hijinks ensue, with walkers, wheelchairs and portable oxygen tanks in place of barbed wire and Steve McQueen’s soaring Triumph motorcycle.

Thompson studied science at the University of Queensland while serving in the Army’s medical corps before pursuing his true calling, starting with a role in daytime soap Motel and later landing the lead role in TV series Spyforce. (One episode featured a six-year-old Russell Crowe, now a close friend.) Thompson never stopped working after his breakout film role in 1971’s Wake in Fright. He’s played a horseman in The Man from Snowy River, an officious bully in Merry Christmas Mr Lawrence, a fiery soldier in Breaker Morant, and a Tatooine farmer in Star Wars: Attack of the Clones. But until now, he’d never played funny on screen.

“I love comedy but comedies just never came my way,” he says. He rewatched Charlie Chaplin in The Tramp and found physical inspiration for his Never Too Late character, an amiable old gent struggling with memory loss. “He’s not without depth but he’s a simple man,” he says. “And that simple man is therefore available to all men. Having gone into homes for the aged and met a number of people of advanced years I’ve seen that, given the opportunity, the child in that person reappears. All the artifice falls away.”

Thompson shot scenes on Mondays, Wednesdays and Fridays; he spent alternate days on dialysis and on the seventh day he rested. Tricky, but not as complicated as the shoot for High Ground. The frontier western had its genesis when Thompson read Eric Willmot’s book Pemulwuy: The Rainbow Warrior, about the famous resistance hero. He took the idea of a film about Indigenous resistance fighters to Stephen Johnson, his director on 2001’s Yolngu Boy, and Johnson came back with a script, by Chris Anastassiades, set in far-flung Arnhem Land.

Thompson was told he’d need dialysis for the rest of his life just as everything slotted into place for a film he’d spent nearly eight years getting off the ground. “I couldn’t believe it,” he says. “We’ve managed to finally get it together and I’m not going to be able to do this.” Rescue came in the unlikely form of a purple truck: the mobile dialysis unit run by Purple House, an Indigenous-owned health service based in Alice Springs. Thompson knew Purple House CEO Sarah Brown from the Garma Festival and when the board heard of his dilemma they offered to help, making Thompson the first non-Indigenous person to be dialysed in the brightly painted truck. “I would finish shooting at 5 or 6pm, go onto dialysis at 7pm, come off at midnight, go to bed at 1am, get up at 6am in the morning, go to work,” he says. “In 40 degree heat. But I was really happy we were doing it and it was happening. I was in my element.”

In September, High Ground was brought home to Arnhem Land with special screenings in the remote communities of Yirrkala and Gunbalanya. “I wasn’t there of course,” Thompson says, “but I recorded a little message: My name is Gulkala Yurapingu and I’m very proud to be a Yolngu man. This movie is for you.”

Thompson owns farmland in the hills above Coffs Harbour, but has been seeing out the pandemic on his nearby Woolgoolga acreage, with the birds, the kangaroos, and wife Leona. (In a 2015 memoir, her sister Bunkie detailed the 1970s ménage à trois relationship they famously shared.) “Le and I have been together 50 years and neither of us is going anywhere,” he says. “[During lockdown] it felt like every day was Sunday and we’d just sit there by the pool and talk, enjoy each other’s company in this little piece of paradise we live in.”

He hears the word “retirement” and it sounds like deprivation. “People say, ‘Are you still working?’ and my answer is always, ‘Is that an offer? Show me the script. Are we financed yet?’” He taps his fingers. Strokes his beard. “I love acting.” Pause. “I love it. It’s problem-solving and it’s research and ‘Who is this person? What year is it and where did he go to school? Is he an only child, what’s his favourite song, who are his heroes?’ All children act in some way or another but then in adolescence they’re told, ‘Don’t be silly, stop playing your fantasy games, just decide who you are’. I never did. I don’t think actors decide in that way who they are. You don’t have to.”

Gifted actor. Activist, philanthropist, scholar. Knockabout Aussie bloke. Keeper of the culture. Thompson regrets none of it, although losing a substantial sum of money on his investment in the Blue Mountains pub Hotel Gearin in 2011 was, he says, “very unpleasant”. Also, he’s not thrilled about being pipped by Liam Neeson for the lead in the 1994 Oscar winner Schindler’s List. But he doesn’t dwell; Taoism taught him that holding onto regrets only causes harm.

He’d planned to celebrate his 80th birthday in August with a fundraising gala in Sydney for the Jack Thompson Foundation, until Covid-19 shut it down. But no regrets. Instead, he celebrated with Leona, their son Billy and a handful of friends at Woolgoolga. There were guitars and didgeridoos, fireworks, a lamb on a spit. Thompson played his blues harp. Artist Reg Mombassa sketched his portrait, a preposterous Jack/Robert the Robot hybrid “with these mad wheels underneath”. “It just pleased me so much,” he says.

Jack Thompson is a dream interview subject. Just let him talk and, if you’re lucky, he’ll even write your ending for you.

I have what I have had, say I

And that’s rich.

It’s a line from another of his dad’s poems. “It’s very rich, what I’ve had,” he says. “Fortune’s darling. Wow. Out of the nest into the Children’s Seaside Hotel, into the Thompson family, into the renaissance of the Australian film industry, da de da, hello, hello!” His 80-year-old body vibrates with a rumbling, full-body laugh. “Extraordinary,” he says. Shakes his head. “Just extraordinary.”

Never Too Late is in cinemas from Thursday. High Ground will be released next year.

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout