Abducted, shackled, assaulted: a backpacker’s horrific ordeal

A young backpacker is among women lured to remote properties.

She was 24 years old and already a seasoned traveller, like many Europeans who came of age in an era of cheap airfares and Airbnb. She had trekked the mountains of Central America, travelled around China and visited South Africa to volunteer in wildlife parks. She was studying in Belgium and nursed a dream of working with animals, but in late 2016 she postponed her studies to tackle her biggest adventure: a backpacking trip around Australia. Arriving in Sydney at the start of summer on a 12-month working holiday visa, she embarked on a popular pilgrimage — a walk in the Blue Mountains, followed by a trip to Tasmania to see that island’s famous wilderness, then back to Melbourne. By late January she was en route to Adelaide; she planned to tour Kangaroo Island and then head north to Central Australia.

A diminutive young woman who spoke basic English, she was travelling alone but felt secure. To her Australia was “a safe place, because the people were so friendly and nice”. To qualify for a one-year visa extension she needed to clock up 88 days of rural work, and a cousin had told her she could find jobs on the Gumtree website. So two months into her trip she posted a notice seeking farm work or fruit picking, and almost immediately got a reply: Would you be interested in rearing baby calves on a farm 2.5 hours from Adelaide? Accommodation provided… My name is Max and we will be working on one of many farms in South Australia owned by a company called Genesis Inc. The pay was $20 an hour.

In their online exchanges she told Max she was looking for five to six weeks’ work and he suggested she catch a bus to the town of Murray Bridge, an hour’s drive south-east of Adelaide. One of our workers will pick you up and take you to one of our farms in Lameroo, Max said, as a French girl has just been taken on to fill another job. On February 9 she stepped off the coach in Murray Bridge on an oppressively hot morning to be met by a tall, lanky 50-ish bloke dressed in black workpants and a grey singlet. This was Max, or perhaps Mark — she would later struggle to remember how he introduced himself. He had a head of dark brown curls and a thick goatee, and he ushered her into his dusty red HiLux ute for the long drive to Lameroo.

They headed out of town on a back road, past dairy farms and small settlements until the trees became sparser and the pastures flattened out into rubble-strewn grazing plains blotched with dazzling white salt pans. Max/Mark griped about the problems he’d encountered with farm workers who turned out to be drug addicts, telling her he preferred women workers because they were gentler with the calves. They came to a small town straddling a wide river, which they crossed on a six-vehicle ferry, and the road skirted the shore of a huge lake. The briny smell of ocean was in the air and the temperature was climbing into the high 30s when they crossed another river, then passed more farms, a burnt-out car and endless scrubby flatlands until finally, after more than two hours, they drove through a steel cattle gate and up a dirt road to arrive at a low-slung cinderblock shed with a corrugated iron roof.

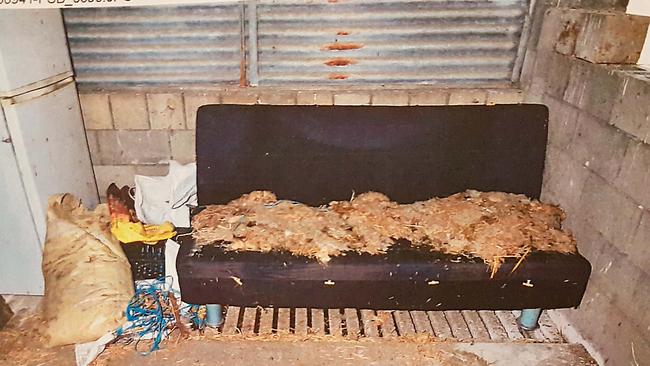

Max was talking about the work they’d be doing on the farm as he led her inside to gaze over the shed’s dingy interior: walls streaked with bird shit, a dirt floor scattered with hay, a hum of insects, an empty chicken coop next to a row of vacant animal stalls, and in one corner a grubby black sofa next to a battered, disused refrigerator. The place was clearly designed to house animals — no running water, no electricity, no toilet and no bed. The realisation that she was expected to sleep here was still sinking in when Max said something strange and unexpected: he wanted to check the bottoms of her feet for needle marks, so he’d need her to lie face-down on the sofa.

She would later say she felt stupid and naive for allowing herself to be manipulated into such a dangerous situation, alone with a man she didn’t know on an isolated Australian farm whose location she could only guess at. “Sometimes I think it’s a curse to be born a woman,” she said. “I think we are not safe at all.” Because “Max” wasn’t called Max, or even Mark, and they weren’t in Lameroo. There was no company called Genesis Inc, no network of farms employing French girls. And when she lay on the sofa as instructed, she felt something hard pressed into her shoulder, and Max told her he had a gun as he pulled her hands behind her back and bound them with cable ties.

“You’re more likely to have a flip-flop blowout than fall victim to crime while you’re travelling Down Under.” — Tourist advice from worldnomads.com

In June 2013, a 45-year-old sexual predator from Queensland named Peter Van de Wetering began placing advertisements on Gumtree and backpacker chat sites seeking young women to work as farmhands or nannies. A 19-year-old German woman on her first trip to Australia answered and agreed to catch a bus to Cottonvale, 200km south-west of Brisbane, where Van de Wetering picked her up in his car, gave her a chocolate bar laced with a sedative, tied her wrists with cable ties and took her to a remote shearing shed. There he threatened her with a knife and raped her. When she woke up the next day she was 26km away, clothed but missing her wallet, cash and credit cards. Van de Wetering was jailed for nine years in 2016, the judge noting his lack of remorse and the victim’s ongoing psychological damage.

The following year, Adelaide father of five Roman Heinze began placing notices on Gumtree seeking female backpackers as travelling companions, describing himself as a tall, athletic “easygoing guy” who loved camping. Over the ensuing two years Heinze would sexually assault or attack four backpackers he met through the ads, most horrifically a young Brazilian woman and her German friend, who he drove to an isolated beach near Salt Creek, 210km south-east of Adelaide. There he tied up the Brazilian woman and sexually assaulted her, then viciously attacked her German friend with a hammer, chasing her along the beach in his four-wheel-drive before local fishermen intervened and rescued the pair.

The Salt Creek incident sparked massive international media coverage, much of which could not resist mentioning the outback terror movie Wolf Creek. That film was inspired by Australia’s most famous serial killer, Ivan Milat, who murdered five foreign backpackers and two Australian travellers in the Belanglo State Forest of NSW between 1989 and 1993. Since then other terrible incidents — the murder of British tourist Peter Falconio in remote central Australia in 2001; the stabbing deaths of two backpackers in a north Queensland youth hostel in 2016 — have fed into recurring stories about whether Australia’s reputation as a safe haven for tourists is justified. On backpacker websites, however, the Salt Creek coverage was generally dismissed as a media beat-up. The popular blog Bemused Backpacker berated journalists for “selling fear”.

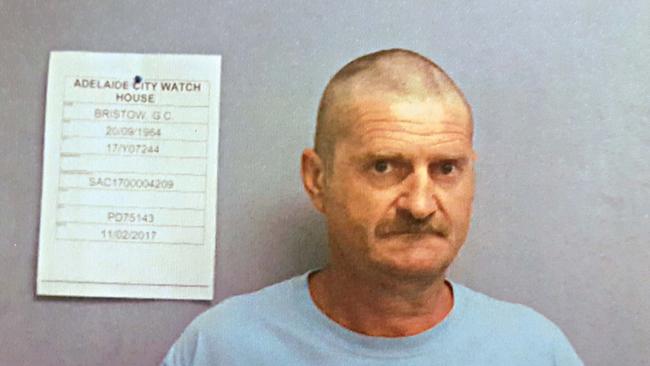

Sixty kilometres up the coast from Salt Creek, in the little fishing/tourist town of Meningie on Lake Albert, lived an often unemployed labourer named Gene Charles Bristow. A rangy bloke with a head of brown curls and a thick goatee, Bristow owned a small hobby farm on the outskirts of the town, where he lived with his wife of 25 years and his son and daughter-in-law. Around Meningie he was known for his many disputes with past employers, including local farmers, the waste dump and the council, against whom he’d brought an unfair dismissal claim after being sacked. “He was a bit of a loose cannon,” says deputy mayor Geoff Arthur. “He’s had more jobs than feeds.” Bristow’s farm ran 40 head of cattle and barely broke even, but in December 2016 he logged on to Gumtree and began seeking female backpackers to come and work for him — 10 months after the Adelaide Advertiser had revealed that Roman Heinze used Gumtree to lure his victims to Salt Creek.

At first Bristow’s clumsy pitch deterred any takers. He peppered women with questions about their age and whether they were travelling alone, explaining that he only had accommodation for one. To “French girl looking for a job” he said he was seeking someone to rear calves on a farm two hours from Adelaide. To a traveller called Paula he explained that he preferred female workers because “guys are a bit rough with baby calves”. By January 2017 he had crafted more credible-sounding details: he said his name was Max and he worked for a company called Genesis Inc; he spoke of a network of farms in Lameroo and elsewhere. He also began shopping on eBay, checking the price of shackles and the sedative Rohypnol, and eventually buying a fake gun and a set of novelty handcuffs.

In the first week of February 2017, 24-year-old Belgian backpacker Lucie Arnaud* took the bait and agreed to meet Bristow at Murray Bridge. Two days before she arrived, he drove into town to buy plastic cable ties at the local hardware shop.

Last month, Arnaud returned to South Australiato tell a District Court jury about the terrifying ordeal she had endured at Bristow’s hands after arriving at his pig shed on that scorching summer day. After trussing her with cable ties, he attached metal chains to her legs, rolled her onto her back and began pulling her clothes off. Over the next 24 hours he would strip her naked, except for her bra, and sexually assault her several times by digitally raping her, fondling her breasts and kissing her, leaving the shed periodically only to return and assault her again. The sofa on which Arnaud was trussed sat on a metal grate, below which was a shallow pit designed to collect animal faeces. Bees and flies buzzed incessantly around her, and she could catch only a glimpse of empty paddocks outside. It felt, she said, as if she were an animal or a slave. “I was very frightened and confused. It felt like it wasn’t real.”

Bristow told her he worked for an organisation that kidnapped women and was in league with local corrupt police. Attempting to escape was pointless, he warned, because the surrounding area was infested with snakes, and if recaptured she would be dealt with more harshly and possibly sent to Sydney. Others in the organisation were crueller, he said, and had drugged their captives. Bristow described himself as one of the nice guys; nonetheless, he would shoot her if she tried to escape.

Alone with her terror in the hours when her kidnapper was gone, Arnaud’s thoughts turned to her family in Belgium and how long it might be before they realised she was missing. “I thought that I wouldn’t see them again,” she said. “I thought that it would take a long time, that they wouldn’t notice that I’m gone, or that I was going to die there.” She could not have known it, but she was only a short walk from the farmhouse where Bristow’s wife, son and daughter-in-law were going about their lives oblivious to her plight. Nor did she realise she was only 500m from the main street of Meningie and less than two hours from Adelaide, for she had been driven here on a circuitous two-hour route through backroads designed to convey an impression of outback isolation.

As the afternoon heat began to abate on that first day, Bristow returned to adjust her shackles so he could more easily assault her. He had taken her mobile phone and the suitcase containing all her clothes, leaving her with only her backpack and a sweater to cover herself as dusk approached. He left her with an arm and a leg chained to the wall, not realising that her backpack contained a laptop and an internet dongle. As the light faded, Arnaud managed to open the fridge and locate a stash of small metal hooks inside it. Using one of the hooks, she laboriously worked at the bolts on the metal shackles, finally working them free just after 8pm. Retrieving her laptop and USB dongle, she managed to find a mobile connection and began sending pleas for help over Facebook.

I have been kidnapped, she messaged a friend in Belgium. No joke. Got my chains loose. On laptop now. Call police and my parents. After sending similar messages to an aunt in Belgium and two backpacker travel companies, she managed to speak to a friend in Cairns over a shaky audio connection. Unable to give her precise location, she listened while her friend contacted police, and then the connection dropped out. Scrolling through Google, she found the South Australian Police Association website and sent a desperate message: Been kidnapped. Murray Bridge to Lameroo I think. A cow farm. Crossed two ferries. Got chains loose. Afraid to run away. He might chase and shoot me. Please help look for me. Please, please, I’m so afraid. Please. I’m on a farm somewhere. He drives a red pickup.

After 23 minutes the internet connection dropped out completely and Arnaud switched her laptop off, afraid that Bristow would see the glow of the screen. Too petrified to attempt an escape, she returned to the sofa, reattached the chains and waited for her kidnapper to reappear.

By next morning, Murray Bridge and its surrounds were swarming with more than a dozen police cars from the local CIB and Major Crime Investigation. Overnight, SA Police had received multiple alerts from Lucie Arnaud’s family in Belgium, from her friend in Queensland, from Belgian police and backpacker organisations alerting them to her kidnap. A police plane was circling over the region, looking for red utes. Just before midday, police held a press conference to express grave concern for Arnaud’s safety, later appealing to her kidnapper to release her.

Arnaud had woken naked on the sofa that morning after a virtually sleepless night. Bristow arrived carrying breakfast, which he allowed her to eat before again sexually assaulting her. When she vomited, he laughed and asked her if she always did that in the morning. It was another blisteringly hot day, and when Bristow returned he was carrying a bucket of water and a cloth, allowing Arnaud to clean herself before he assaulted her again. Then he offered her the possibility of release, claiming to have found a replacement girl. He was, he said, weary of being involved in this business. Overhead, Arnaud heard the drone of a circling plane.

Some hours later, the police aerial patrol spotted Bristow’s red HiLux ute on his property and reported it. Around 2pm police pulled him over on a back road near his farm, checked his driver’s licence and photographed him. Bristow rushed back to his property and ordered Arnaud to get dressed, saying he was taking her to Murray Bridge to catch the last bus back to Adelaide. Hustling her from the shed, he told her to run to a nearby coppice of trees where he picked her up in his wife’s Holden Commodore. Ordered to lie on the back seat, Arnaud felt the car bump down dirt roads for some minutes and then stop. Bristow bundled her out with instructions to wait until he returned. Too terrified to run after hearing his claims about corrupt police, she did just that. Shortly after, Bristow returned in his ute and they drove to Murray Bridge, arriving just before 5pm — too late to catch the last bus.

Just over an hour later, an off-duty cop drove out of a fast-food restaurant in Murray Bridge and saw Arnaud walking past. Sergeant Andrew Kemp checked the woman’s appearance against the photo bulletin that was circulating and called out to her. When Arnaud kept walking, Kemp got out of his car and began calling the names of her family members. Looking dishevelled and fearful, her face and arms marked by insect bites, Arnaud barely looked at Kemp as he approached her, waving his police ID. “How do I know it’s not fake?” she asked.

Bristow, it transpired, had earlier dropped Arnaud at a nearby motel, ordering her to book a flight back to Belgium before driving off. Traumatised and bewildered, she had showered, gone to McDonald’s and failed to contact police. A female cop who interviewed her later said: “She had heard that police were corrupt… She appeared to be quite intimidated, afraid, and sort of cowering from us.” Eventually persuaded to describe what had happened, Arnaud identified Gene Bristow from photographs, and police raided his farm the next morning. Entering the pig shed, they found the sofa buried under hay bales; when they encountered Bristow he had shorn off his beard and hair. He was arrested on the spot.

In October 2017, the two women who survived the Salt Creek attacks appeared on 60 Minutes to share the details of their ordeal, describing how Roman Heinze savagely assaulted both of them and relentlessly chased the young German woman through the sand dunes in his four-wheel drive, ramming her with his bullbar as blood streamed from the hammer wounds he’d inflicted to her head. Wolf Creek, it seems, was not such a far-fetched comparison. It’s now known that Heinze, who is serving a 22-year jail term, had previously lured a Japanese backpacker to the same beach but left her unmolested after she posted photos of the location on social media; he had also sexually assaulted two backpackers he met in Adelaide through Gumtree, and narrowly escaped conviction for another violent sexual assault.

Since Heinze’s crimes there has been no shortage of backpacker victims in the news. In 2017, a 53-year-old Mildura farmer pleaded guilty to sexually assaulting a Dutch backpacker working on his property; in October last year a Queensland farmer was charged with the rape and sexual assault of a 23-year-old British backpacker he had recruited as a worker; that same month 23-year-old Marcus Allyn Keith Martin pleaded guilty to kidnapping and raping a young woman from Liverpool who was backpacking around Queensland. Martin had allegedly befriended the woman and held her captive for weeks, damaging her passport to dissuade her from escaping; her plight was discovered when she walked into a north Queensland petrol station with blackened eyes and bruises, looking distressed and “zombie-like”.

Clive Small, the retired NSW cop who put Ivan Milat behind bars, has noted that backpackers are uniquely vulnerable to violent predators — young and seeking adventure far from home, they often travel alone and seek work in remote locations. In January, British filmmaker Katherine Stoner released a half-hour online documentary, 88 Days, detailing backpackers’ stories of sexual harassment, assault and economic exploitation on Australian farms. Alarming headlines about these issues have appeared with almost seasonal regularity since the Milat killings nearly 30 years ago, yet Australia’s reputation as a safe destination endures. Tourist numbers have soared since 2012; when backpacker numbers declined in 2016, the dip was blamed not on the Salt Creek incident but publicity around the Federal Government’s looming backpacker tax.

In the wake of the Bristow case, South Australian police issued a safety alert advising young tourists to avoid travelling unaccompanied to farm work and to post photographs on social media of any car they rideshare in. Whether backpackers will take heed is uncertain. Tourism Australia reports that its 2018 survey of young people in the UK and Germany shows recent kidnapping incidents have had “no discernible impact” on their view of Australia. Likewise, the chief executive of The Global Work & Travel Co, Jürgen Himmelman, says his company rarely receives any inquiries about safety. Echoing the views of many in the industry, he says incidents of serious crime against backpackers are extremely rare, and his company receives a lot more inquiries about wildlife dangers than human ones. “Australia’s reputation as a safe destination has been impacted much more by Steve Irwin than anything else,” he quips.

That Gene Bristow used the same modus operandi as Roman Heinze was apparently no coincidence — when police seized Bristow’s computer they found internet searches related to the Salt Creek kidnapping. Eerily, he had met his victim in Murray Bridge exactly one year after Heinze picked up the Salt Creek victims in Adelaide.

By the time Bristow went on trial last month, evidence of his guilt appeared overwhelming. Police had compiled 44 pages of his duplicitous online exchanges with Arnaud and other backpackers, along with records of his online shopping for Rohypnol, shackles, handcuffs and a fake gun. Arnaud had suffered injuries to her wrists and vagina consistent with the assaults she described, and her mobile phone was found dumped in one of Bristow’s water tanks. Police found metal shackles at the bottom of a well on the farm and a fake gun discarded in a paddock. Bristow’s son and daughter-in-law agreed to give damning testimony against him, revealing he had lied to them about his whereabouts on the days of the kidnap.

Yet Bristow, like Heinze, chose to profess his innocence and portray his victim as a liar and fantasist. Perhaps most egregiously, he suggested Arnaud had mimicked the Salt Creek incident to cover the fact that she couldn’t hack farm work. Forced to testify, Arnaud endured the grilling from Bristow’s lawyer with stoicism, giving evidence in simple declarative English while an interpreter sat next to her. But shown a photo of the metal shackles that had held her legs, she broke down in tears.

By comparison, Bristow delivered rambling testimony in which he bragged about his welding skills, jousted with the prosecutor and tripped himself into contradictions. He claimed Arnaud had been free to visit his farmhouse at any time, yet admitted his wife and son had no idea the young woman was in the pig shed. The fake gun, he insisted, was a present for his grandchildren and the handcuffs were a saucy anniversary gift to his wife. The phony company name Genesis Inc was “not entirely dishonest” because his name is Gene, and anyway, “You can call yourself what you like online”. Pressed to explain his false claims about multiple farms around Lameroo, he replied: “Can’t answer that.” The jury took less than three hours to convict him on six charges of aggravated kidnapping, rape and indecent assault.

Three weeks ago, Arnaud flew from Europe to Australia once more for a pre-sentence hearing in which she sat in the front row of an Adelaide courtroom, flanked by supporters, as prosecutor Michael Foundas read out her victim impact statement. “Every time I think about what happened to me in that shed, I break down in tears,” she said. “I get terrible headaches and sometimes feel my head is going to explode.” More than two years after the ordeal she still suffers flashbacks, consults a psychiatrist and takes medication to quell her anxiety and periodic sleeplessness. “I was locked in chains, held against my will and had to endure things nobody should have to endure… I still don’t like going to places where there are lots of people. Even going to the shops can be scary for me. It’s only in the last few months that I have had the confidence to drive my car alone. Even then I have to be sure someone is waiting for me.”

Bristow stood in the dock as the statement was read, staring straight ahead. He had yet to be sentenced as this story went to press but his decision to force Arnaud to testify is likely to result in a heavy jail term on charges that carry a life sentence.

In Meningie, locals express bewilderment at his crimes, along with uneasy questions. “He wasn’t the sort of bloke who warmed the cockles of your heart,” says one neighbour, “but I would never have imagined him capable of something like this. You wonder what he was planning to do with her. What would have happened if she hadn’t had got those messages out on her laptop?”

“He just seemed like an ordinary bloke to me,” sums up Tracy Hill, a local councillor whose husband briefly worked with Bristow. “You could walk past him in the street and not give him a second glance. You never know, do you?”

*The name of the victim has been changed.

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout