No one pays attention to the half-tonne whale skull travelling on the back of the tilt-tray tow truck through Darwin’s busy streets. It looks like an oddly shaped lump of wood: bronze, brittle and jagged. There’s no hint of the extraordinary story in its long, arboraceous appearance. Jared Archibald stands outside the taxidermy workshop at the Museum and Art Gallery of the Northern Territory when the truck reverses in. The skull’s arrival is much less eventful than when it was first brought in by chopper in April 1981. Those blokes came in too low and smashed the whale’s nose off. They also dropped one jawbone into the ocean on takeoff.

Jared gets up close to the bone. It’s still in good nick, but 22 years in storage hasn’t done it any favours. “Darwin wrecks everything,” he says. “It wrecks marriages, it wrecks cars, it wrecks buildings, wrecks everything. It is the worst place in Australia to try and keep anything for any longevity. And we, as a museum, know that first-hand.”

Jared rubs his hand along the craggy edge of the creature’s rostrum. He’s been tasked with preparing the skeleton for display – the same job his father Ian had 40 years ago, when the whale was recovered from a remote Northern Territory beach.

Like many Territory tales, this one starts tall. It was the early 1980s and the story goes that a fisherman was flogging whale vertebrae around Darwin as garden furniture seats. He’d come across the skeleton in a remote area off Cape Hotham, south of Melville Island, and saw a way to make a buck, likely unaware whales were federally protected. Word eventually reached the museum which, presumably after some stern words (it’s rumoured the fisho was charged with an offence, but no record of it could be found), retrieved as much of the outdoor furniture as they could, then hired the man and his 40-foot boat to help their team recover the rest of the bones.

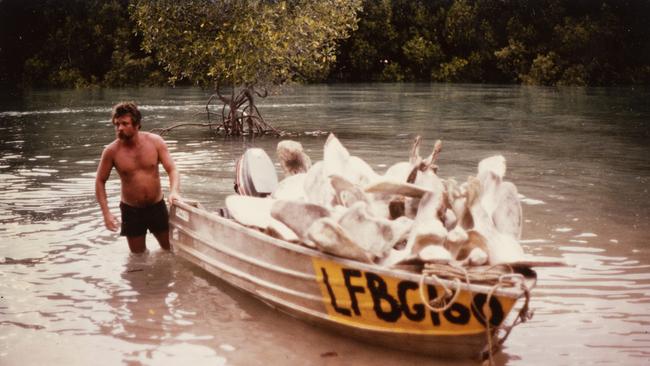

The museum’s taxidermist, Ian Archibald – now 82, retired and living in Alice Springs – remembers arriving at the mangrove-fringed beach to find “a jumble of bones” moving in and out with the tide. “There was absolutely no sign of any flesh on them so they must have been out there for a long time,” he says.

Ian and a couple of other museum workers set about piling the bones into a tinny, then ferrying them out to the bigger boat. “It was pretty overloaded,” he recalls. “OH&S probably wouldn’t have approved of quite a few things we did back then. We couldn’t take the jaw bones or the skull itself because they wouldn’t fit in the boat. The jaw bones alone were longer than the tinny.” That’s how the helicopter became involved. That’s how the whale lost half its head.

There were other bones missing too – smaller ones like the phalanges and pelvis, likely washed away. “Some could be whale bone furniture around Darwin now,” Ian says.

When the skeleton arrived in Darwin, another problem came to light – there was nowhere to put the thing. The old museum had been trampled by Cyclone Tracy in 1974, and since then its collection and workers had been distributed around Darwin. Ian operated out of a hired space above Dizzy’s pinball parlour alongside the snake curator and his live charges – death adders, king browns and taipans. It was no place for a whale. It simply wouldn’t have fit. It’d been a stretch preserving Sweetheart there – the museum’s 5.1m saltwater crocodile famous for attacking dinghies in the Finniss River in 1979. Ian taxidermied Sweetheart back to life and it’s still one of the museum’s most-loved displays.

And so the whale spent the next decade migrating to various storage facilities, including the old Parap Picture Theatre, until the new museum’s maritime gallery was completed. That was Ian’s cue to restore the whale. He went to work reinforcing the bones with polyester resin, laying them out in order in the museum car park. On account of the missing jawbone, they sawed the whole skeleton in two and prepared two-thirds of it as a side-on display rather than a full mount. The process took about 12 months.

“It was the biggest thing we’ve done,” Ian says. At the other end of the scale, his job involved putting pins through mosquitoes for the insect collection. “That’s just as challenging.”

In 1992, the 21.9m, 2000kg skeleton was finally installed on the wall of the museum’s maritime gallery overlooking Darwin Harbour – a body of water better known for box jellyfish and crocs than for whales. But if you ask experts, whales in the Northern Territory are not unusual at all.

The Bryde’s whale is stranded between Kakadu and Katherine, about 100km from the nearest ocean. Not an actual bone-and-blubber whale but an image of one painted on a rock face by First Australians in the early 20th century – quite recently in indigenous history terms. There’s another on the Wessel Islands, off the coast of East Arnhem Land, showing ancient Indonesian hunters, known by locals as Wurramala, harpooning a large whale, and likely more scattered around the coast and beyond. Known as nawu nawu in several dialects, whales hold spiritual significance for many Aboriginal people. They are a totem in some areas, and sometimes are declared sacred when they wash up on Territory shores.

Despite this long documentation of whales, it’s still not what people expect in croc country, says Dr Carol Palmer, cetacean and marine megafauna researcher at Charles Darwin University. “People still say to me, ‘What, we’ve got dolphins and whales here in the Northern Territory?’”

Palmer began the first cetacean research in the Northern Territory in 2007, working alongside traditional owners recording the traditional science as well surveying the current population. But she confesses it’s difficult to get people to take notice of what’s happening in NT waters. “We are bottom of the pile here as far as the marine world goes, but it actually is a really interesting marine world,” she says.

Of the 18 species of dolphin and whale recorded in Territory waters, four are considered resident – the Australian snubfin dolphin, false killer whales, humpback dolphins and dwarf spinner dolphins. Killer whales, Bryde’s whales, humpback whales and short-finned pilot whales have all been sighted. Through satellite tracking and DNA samples, Palmer and her colleagues believe they have identified a unique population of false killer whales in the NT. “That could very much be the case for a number of species here,” she says.

But some of the whales recorded in the Northern Territory have been far from where they were supposed to be, Dr Palmer says. In September 2020, humpback whales were spotted slowly winding their way up the East Alligator River in Kakadu; a rare pygmy sperm whale floated into Mindil Beach in 1995; a sperm whale washed up on Goulburn Island in the 1980s, and another sperm whale ran aground at Darwin’s popular Casuarina Beach in 1993.

Ian and Jared both remember that one. The Army towed it around the harbour using a barge, and then the navy offered their ship lift so the museum could salvage the skeleton. With the help of a local panel beater who had worked at the Albany whaling station back in the day, they flensed most of the carcass, but eventually the smell got so bad they had to bury the full head at the dump and wait for the meat to rot off the bone. “It must have weighed 40 tonne or something – that’s a lot of meat to be going off in the tropical sun,” recalls Ian.

The pygmy blue whale was strange too, says Palmer, although she has seen blue whales while sailing in yacht races between Darwin and Indonesia. Apart from that 1981 stranding, Palmer says the NT hadn’t recorded any other blue whales until recently. In May this year, mining company Woodside said their trained marine mammal observers reported a number of pygmy blue whales about 187km from Darwin.

Palmer says the recent sightings, along with the resurrection of the 1981 skeleton at the museum, could prove crucial in attracting attention to what goes on under the water’s surface in the NT. “It’s really important for the rest of Australia to know these are our stories.”

The taxidermy workshop at The Museum and Art Gallery of the Northern Territory is a jungle of bones and feathers and skin. A flock of magpie geese hangs from the ceiling. A 2.5m saltwater croc perches atop a bench. Almost every other surface is occupied by a piece of whale.

Jared stands among it all, surrounded by upwards of 100 bones, repeating his father’s work of piecing them back together. “Every time Dad rings me he says, ‘How’s that whale going?’ Then he just laughs his head off.” It’s not that the Archibalds resent the whale, exactly. It’s just that it’s such a lot of work. And after two decades in storage, Darwin’s wrecking abilities – the heat, the humidity – have made the job even bigger. Jared shakes his head, and wedges his way into the backroom alongside 63 vertebrae.

Jared, now 52, grew up around animals: some alive, some not. Roadkill in the freezer, skins drying out on the porch – that kind of thing was common in their suburban Darwin home. Occasionally, he recalls, there was a live crocodile in the bathtub. “Little ones and not all the time,” he clarifies.

The pygmy blue whale simply falls in with a childhood of unlikely wildlife cameos. “The skull sat at the back of the museum building and I remember as a 12-year-old thinking ‘this is amazing’, not knowing it was going to be my bane,” he laughs, walking to another room where ribs are laid out like an enormous Lego set.

Jared followed his father into taxidermy, helping put the whale on display in the early 1990s. Then, nine years later, after Ian had moved to Alice Springs, the gallery underwent maintenance and Jared was tasked with pulling it all down. It took months to disassemble. “Absolute and utter disappointment” is how Jared recalls the deconstruction of the giant skeleton.

Although Jared moved into his current position as the museum’s curator of Northern Territory history in 2014, the whale has seconded him back to the preparatory work of his early career. He confesses he’s more passionate about the stories that go with the objects than preparing the objects themselves. And there’s never a dull moment in his curating role. “This morning a school brought in a skeleton they had in their labs – they thought it might be a real person,” he says. “It wasn’t. It was a very good plastic cast.” Someone else phoned up about a pirate ship (“it’s not a pirate ship”) and he’s been talking to a man interested in donating an identity disc handed out to Aboriginal people in the 1930s as a way of controlling their movement around Darwin (“an incredible find, they only minted 500 of them”).

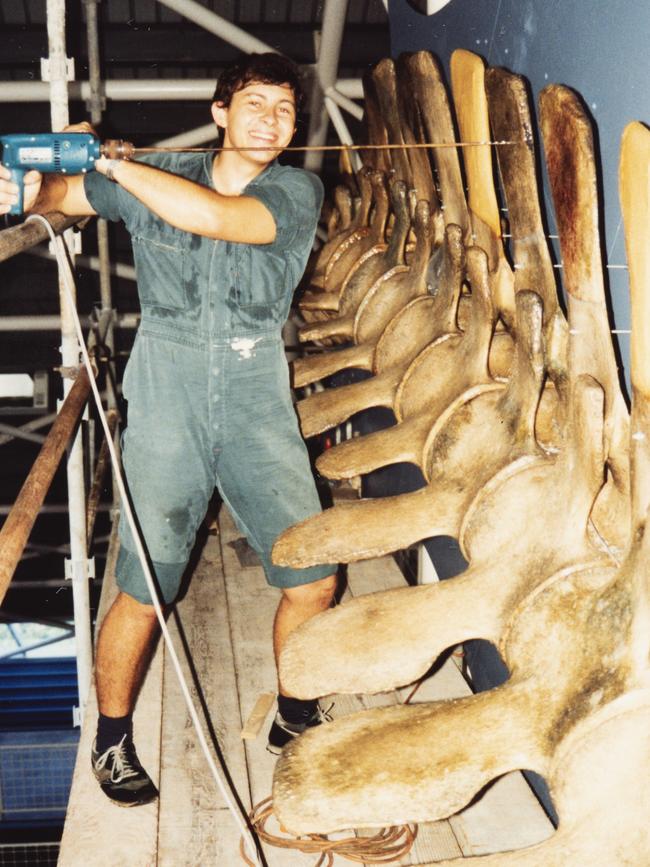

He goes out the back door of the workshop to a table covered in old-school cardboard hot chip containers, each with a Paddlepop stick inside. They’re the best tools for mixing the resin he needs to impregnate the bones, Jared explains. “It was a more difficult job for Dad,” he says. “They had to harden every bone as well and drill all the holes and anchor all the big threaded rods. I’ve had to do a lot of bone repair and redo some of it that was damaged from being in storage so long, but a huge amount of the work that had to be done has already been completed.”

Vertebrae, ribs, chevron bones all had to be treated again. The missing phalanges, three ribs, one neck vertebrae and nine caudal vertebrae had to be made from scratch. Jared’s been working on them for months. The only thing left to prepare are the skull and jawbone, weighing in at 600kg. They’ll need a lot of hot chip containers.

Although his background is in taxidermy, working with animal skin, bones are in Jared’s bones. Preparator work has always been part of the job, and he’s been going on fossil digs in Central Australia since he was a kid. He even ran them for a few years. That, he confesses, is much more exciting than the whale. In that high-stakes, slow-paced work, where “it’s easy to accidentally destroy something millions of years old”, he once unearthed a thylacine jawbone. “It’s so cool. The site has the remains of thousands of animals in it – megafauna that’s seven million years old.”

The whale is part of the reason Jared missed out on the dig this year (the other reason was Covid), but his father Ian did manage five days in the desert, helping unearth the skull of a Plaisiodon – a rhino-sized wombat.

But with the whale – Jared has named it Melville as a nod to both Moby Dick and where it was found – it’s not just about keeping bones intact. The other challenge is getting the 2000kg creature up on the wall of the museum all over again.

A couple of weeks later, Jared paces over a hugewhale-shaped grid painted onto the floor of the museum’s warehouse where the skeleton was stored for most of the last two decades. “Last time Dad had to do this outside in the car park,” he says. “At least this time I’ve got a fan.” The enormous shed is lined with Indonesian boats and artillery and various other pieces of boxed-up history. A large crate on a shelf holds Sweetheart’s skeleton. In a dark corner is the skull of the Casuarina Beach sperm whale. In the middle of it all Jared lays out sheets of marine ply over the grid, marking them up for the backboard that will be the middle man between the whale and the steel armature that has been installed in exactly the same spot as last time. There’s no room for error. Even 1mm in the context of a 21.9m whale outline is a disaster.

“You know,” Jared reflects, “I’ve never seen a big, live whale. Ever. I’ve seen pilot whales, up to 20-footers. I’ve seen a dead sperm whale and I’ve seen – no, that’s it.”

His father Ian has seen them, but his review wasn’t glowing. “They’re fairly boring things, I think, whales. Sometimes they’re good, breaching humpbacks are pretty spectacular. But I’ve been there on the Nullarbor and watched the Southern Right whales and it’s like watching a slow-moving submarine. I can’t get excited about them.”

But both of them realise their work is about something much bigger than the whale. Like dinosaur bones, the pygmy blue whale bones are evidence of things old and unusual; relics of things lost and found. And the Archibalds appreciate that. The scientific side of it is important, but so too is the public interest. And the interest is there. Last year more than 200 people gathered at a fundraiser for the whale, raising almost $150,000 for its restoration.

“Most people don’t get to see a whale, live or dead, and you cannot understand how big they are until you stand next to one,” Jared says. And ultimately, that’s the role of a museum: to make the inaccessible accessible. “You can look at anything on a computer, in an artwork or a photograph, but nothing beats the real thing,” he says. “And that’s what museums are so good at. Because we hold the objects. You need the real objects to tell you what’s going on.”

Jared kneels down on the board and gets back to work. He calls the whale his “bane”, but there is at least some affection for Melville – this mammal that’s been washed up, piled into a boat, hung off a chopper, made into furniture, put up on a wall, dragged back down again, and that Darwin has tried its best to wreck, as it does everything.

“Once it’s all finished, you’ll be able to stand inside the whale’s head and look up through the rib cage and get an inkling of the biggest animals on the planet. They’re bigger than dinosaurs, one of the biggest animals that ever lived.”

The Museum and Art Gallery of the NT’s whale is expected to be on display in 2023.

Add your comment to this story

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout