The water temperature is bracing and, for the first minute or so, I’m huffing out my snorkel like a steam train. But it’s clear and surprisingly beautiful beneath the surface of Sydney Harbour’s Woolloomooloo Bay. Kelp and other seaweeds dance in unison to the currents. We see some good-sized fish – bream, wrasse and luderick – and some prancing little puffers. Considering we are in the heart of Australia’s largest city, and there’s been a naval base in this bay since 1856, the biodiversity is impressive. The sandstone banks are snarling with oysters. There are four or five different species of kelp, including a beautiful iridescent rainbow- coloured variety. It’s a watery wonderland.

My snorkelling partner, scientist David Booth, dives down and returns with an old bottle. “People have been getting pissed here for the past 200 years,” he says, putting it into a pouch for his collection. “Be careful if you pick one up; they’re a favoured hiding place for blue-ringed octopus.”

Booth, a professor of marine ecology at the University of Technology Sydney, and his wife Giglia Beretta, also a marine scientist, are installing artificial reefs along the flat concrete wharves around the harbour to mimic the rocks and crevices of the natural environment. It’s part of a project called Seabirds to Seascapes, funded to the tune of $9.1m by the NSW government, designed to repair damage to the marine ecosystem caused by over 200 years as an industrial waterway. In announcing the initiative, environment minister James Griffin acknowledged that Sydney’s water quality has improved so much in recent decades that now “we all delight at sightings of whales and seals in the harbour”, and said now was the time to “supercharge our restoration efforts”.

Sydney Harbour is certainly on the mend. The councils of the Parramatta River catchment have set themselves a goal of making the river and the upper harbour “swimmable by 2025”. Seals have indeed returned and now lounge around on rocks below the Opera House. The new reefs are sprouting along with seagrass, and kelp forests are being planted to encourage biodiversity. Booth and Beretta’s artificial seawall in the harbour is now home to endangered seahorses and other species.

But this place cannot entirely escape its working-class past. “The harbour is like someone who used to smoke,” says Professor Emma Johnston, inaugural director of the Sydney Harbour Research Program. “We’ve got historical legacies of contamination that lurk in the sediments.” Cleaning up that sediment would cost billions. And there are new threats and dangers, such as microplastics. Vigilance is required. But still, she is hopeful. “Despite the fact that we have six million people living around it, we still have this harbour that has immense biological diversity,” Johnston says. She can envisage a time in the not too distant future when people will wander down from the CBD at lunchtime for a swim – with the reassurance of a shark net – at Farm Cove in front of the Royal Botanic Garden. “Wouldn’t that be wonderful,” she says. “And it could actually happen.” A summer plunge in the harbour, with the Opera House and the bridge as a backdrop, would surely be a global sensation on Instagram.

Few people can testify to the rehabilitation of Sydney Harbour like Pat McDonough, 75, who has lived her entire life within a skip of the water. One of the terrace houses her family rented when she was a kid, in Fitzroy Avenue, Balmain, faced Cockatoo Island, a few kilometres west of the bridge. Thousands of workers would arrive each morning on green double-decker buses marked Industrial, to catch ferries out to the shipyards on Cockatoo or to work in the dozens of factories on the shores. Her mother was a cleaner and her father was a wharfie. He died when Pat was little, and her mum remarried another wharfie. “My brother went to sea [in the merchant navy] and my cousins went to sea. My uncles all worked on the wharves, or in factories,” she says. “My aunty was the canteen cook at the Lever Brothers soap factory, down on the harbour.”

“The harbour is like someone who used to smoke. We’ve got historical legacies of contamination that lurk in the sediments.”

The family never had a clock in the house; the days were punctuated by the whistles from the factories for clock-on, smoko, lunch and pub-time. And while her house faced Cockatoo Island, the view was obstructed by a factory that made timber boxes. She remembers how they used to float logs up the harbour, chained together, then hoist them into the factory by crane to be sawn into planks and the sawdust would spill into the water. The man on the crane hook was Chooky Fraser, older brother of the swimmer Dawn Fraser.

The Frasers lived around the corner from Pat’s family and they knew them well. Pat was 10 years younger than Dawn, and idolised her. “I can still remember the excitement of sitting by the radio and listening to Dawn’s win at the Melbourne Olympics,” she says. “It was just so unbelievable that a girl I knew from the slums of Balmain – everyone used to call us the slum kids – could be the world champion and famous.”

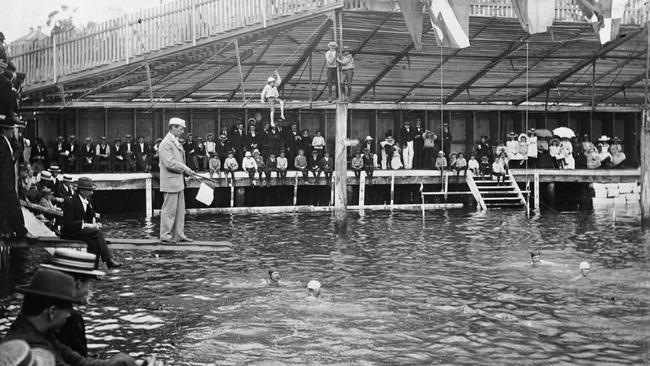

At the age of 10 Pat joined the swimming club at the local Balmain Baths, a tidal harbour pool now known as the Dawn Fraser Baths. Dawn’s cousin Chuck Miranda was the coach and young Pat McDonough spent so much time down at the pool that her mother used to quip: “Why don’t you just take your pyjamas?” She loved it but the water quality, back in the day, was atrocious. “You’d get out of the pool and you’d have grime all over you,” Pat says. “We never thought anything of it.” One year, all the kids in the swimming club broke out in mysterious boils. A stormwater drain flowed down the hill and into the pool, and in heavy rain it would overflow with sewage. Then there was the runoff from all those factories. There were paint factories, soap factories, coal mines, power stations, cattle yards and the state’s biggest abattoir at Homebush. The Union Carbide factory at Rhodes manufactured deadly chemicals, including Agent Orange – used to defoliate jungles in the Vietnam War. This is the sort of effluent that ended up in the tidal pool.

Pat, plucked out of Balmain and sent to the selective Riverside Girls High, a ferry ride across the harbour at Huntleys Point, became a lawyer, working at the Redfern Legal Centre and for various unions. She now lives just up the road from where she grew up, in one of those old Balmain houses with a view of Cockatoo, bought when things were cheap. It’s now worth squillions. “I was a slum kid,” she says with a wry smile. “And now I’m posh.” Her harbour has undergone a similar conversion. McDonough has been swimming in the Dawn Fraser Pool three or four times a week for the past 65 years and through her goggles she’s witnessed a remarkable transformation.

For a start, you can now see the bottom, thanks to the improvement in water quality. Gone is the grime. The fish have returned. A pair of stingrays took up permanent residence in the pool about 15 years ago. “Someone nicknamed them Steve and Bindi but some people didn’t like that,” she says. Even the humour has been cleaned up.

Dozens of other harbour baths, built early in the 20th century all through the upper reaches of the harbour and into the Parramatta River, were closed in the 1950s and ’60s by public health orders due to severe pollution. Now, councils in the upper harbour are busily rebuilding them. At Bayview Park, Concord, great pylons are being driven into the sand, shark-proof nets are being erected and the first new harbour pool to be built in almost a century will open this summer, 10km or so upstream from the Harbour Bridge.

Sydney Harbour’s bays, rivers and inlets reach 30km inland like tentacles along some 300km of shoreline. It is one of Australia’s most recognised and revered natural features, up there with the Reef and the Rock. It’s an ancient river valley that was flooded some 12,000 years ago when the seas rose. “That’s what’s created this really complicated system of waterways,” says Dr Peter Hobbins from the Australian National Maritime Museum. Beneath the waters of the harbour, he says, there might be Aboriginal archaeological sites, because all those millennia ago “it wasn’t underwater, it was the edge of a river” and home to the hunter- fisher-gatherers of the Eora nation.

They would be dispossessed of their ancient lands and their bountiful harbour within a few short years of the First Fleet sailing in through the heads in 1788. John White, a surgeon on the First Fleet, famously wrote: “Without exception, [it is] the finest and most extensive harbour in the universe, and at the same time the most secure, being safe from all the winds that blow.” Its craggy sandstone cliffs and deep waters may have offered safety to ships, but ever since the arrival of the convicts and their jailers there’s been conflict between those who wanted to preserve the beautiful harbour and those who wanted to exploit it.

The very first environmental laws passed by Europeans in this country were about the Tank Stream, the fresh water supply for the new colony that fed into the harbour. Governor Arthur Phillip decreed that there should be no buildings on the banks of the stream, or dumping of refuse in it. When he left Sydney in 1792, after just four years, his ruling sailed with him; the Tank Stream became a fetid sewer spilling into the harbour and new sources of fresh water had to be found for the fledgling colony. By the mid to late 1800s this incredible harbour, which had sustained the Eora for thousands of years, was being fished out. A Royal Commission was called and laws were passed to limit the fishing, but they did not address pollution or the rapid development on the foreshore. It would remain a dump and a sewer for another hundred years.

Sydney is split by the harbour and the harbour is divided by the bridge. On the eastern, ocean side, closest to the heads and surrounded by some of the world’s most ridiculously expensive real estate, with Manly and Mosman to the north and Vaucluse and Point Piper to the south, the tide rushes in and out each day, giving this part of the harbour a daily flush. The water there is generally cleaner. West of the bridge, the upper harbour branches inland for tens of kilometres up the Parramatta and Lane Cove Rivers in what were once working class suburbs. It was here that much of the city’s heavy industry was based in the last century, as it offered “a no-cost waste disposal solution”. A weak tidal flush compounded the pollution problem. In the 1950s a thick black sludge blanketed the foreshore and in the 1960s much of the upper harbour and Parramatta River were covered with green slime. In the 1960s the Maritime Services Board declared the Parramatta River to be “virtually dead” but added that it “couldn’t expect businesses to shut their factories and send their workers home just because they were putting some pollutants in the water”.

A major study later found that concentrations of heavy metals such as copper and zinc in the sediment at places like Iron Cove and Hen and Chicken Bay in Sydney’s inner west were so dense that they were almost economically viable to mine. “In total, 1900 tonnes of copper, 3500 tonnes of lead and 7300 tonnes of zinc have been found in Sydney Harbour,” it stated. “Pollutants entering the Parramatta River during this period [1950s and 1960s] included heavy metals, petroleum hydrocarbons, asbestos, chlorinated pesticides, chlorinated benzenes, polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons and dioxins.” The pollutants would “take centuries to dissipate”, it added.

A significant milestone for water quality came in the 1930s when sewage from the northern suburbs was diverted from the harbour to the ocean; all suburbs on the southern side were connected to ocean outfalls by the 1950s. And then things took a giant leap forward in 1970 when the Clean Waters Act banned industry from dumping its waste directly into the harbour. “That made a really big difference to the industrial pollution,” says Alexa McAuley, an environmental engineer. But there were still significant problems with wastewater and stormwater overflows, and major work was done in the 1990s and 2000s, particularly to reduce sewage entering the harbour in times of heavy rain. “A lot of money was spent on water treatment works prior to the 2000 Olympics,” she says. “We wanted our harbour to sparkle for the Olympics.” Still, after heavy rain, sewage still overflows into the harbour and it is unsafe for swimming.

These improvement works are continuing in places such as Powells Creek, which runs through Sydney Olympic Park. The concrete stormwater drains were recently replaced with gently sloping stone banks and many thousands of native plants were planted along its banks. Block pools were built to establish salt marshes and to collect silt.

In the half-century since the Clean Water Act was passed, the Parramatta River and the upper harbour has gone from “virtually dead” to a spectacular resurrection. The Department of Planning and Environment says water quality at Sydney beaches and in the harbour has improved drastically since it began its Beachwatch program in 1989. In its 2020-21 report, 85 per cent of the swimming sites monitored in Sydney harbour were rated “good” or “very good” and were suitable for swimming “most or almost all of the time”.

Swimmable water quality is measured by the amount of faecal matter it contains: readings under 200 CFU/100ml (colony-forming units per 100ml of water) are considered safe, and most of the time the harbour beaches fall within this range. Apart from isolated spikes (in March this year, after torrential rains, a reading of 4900 CFU/100ml was recorded in the upper harbour at Cabarita) there’s a lot less – to put it bluntly – shit in the water now than there was. In 1989, Sydney’s harbour beaches recorded “low levels of faecal contamination” just 2 per cent of the time – meaning it was unsafe to swim 98 per cent of the time. By 2020, it was unsafe to swim just 7 per cent of the time. On a recent check of the Sydney Harbour Daily Pollution Forecast, all the designated harbour swimming spots were open. At Cabarita, the forecast said: “Pollution is unlikely. Enjoy your swim. Ocean temperature is 18 degrees.”

And so, on a chilly spring day, I decide to take the plunge, not at Cabarita, but in Woolloomooloo Bay with giant naval ships tethered on the other side of the inlet. Marine scientists David Booth and Giglia Beretta have been diving together for 30 years. She grew up in the Caribbean, diving in its tropical waters, and when she arrived in Sydney in 1995 she never imagined much of her work would focus on its industrial harbour.

Booth and I pull on our masks, snorkels and fins to the bemused looks of tourists strolling out to Mrs Macquarie’s Chair. We are very close to where navy diver Paul de Gelder was attacked by a bull shark in 2009. Booth reassures me that riding my motorcycle here was more dangerous than the possibility of a shark attack. As soon as we enter the frigid waters, the hum and the buzz of the city disappears. As we make our way up and down the shoreline, Booth conducts his observations and dives to the bottom to collect old bottles. It is incredibly serene and surprisingly beautiful.

The Seabirds to Seascapes habitat enhancement program involves the replanting of native seagrasses, a support program for little penguins and a survey of fur seals, which have made a triumphant return to the harbour after being hunted almost to extinction in the 1800s.

Sites where they have built the artificial reefs, for example next to the Opera House, are thriving. “We seem to have attracted six or seven new species, including [an endangered] seahorse,” Booth says. They’ve seen other interesting creatures, such as the gloomy octopus. They plan to roll out these artificial reefs to other areas around the harbour on the many hundreds of wharves and jetties.

“I feel blessed that the harbour has been part of my life. Every time I get out of the water I just feel wonderful”

Ben Pitcher, a behavioural biologist at Taronga Zoo, says that 20 years ago it would be incredibly rare to see a seal in Sydney Harbour. But around 2010, a few seals started showing up on the shore below the Opera House. “We’d have one or two and they’d stay for a couple of months and then they’d disappear,” he says. Now there are a group of about eight males that inhabit the harbour for much of the year, heading to Montague Island on NSW’s south coast for the breeding season. Pitcher believes that in the coming years the seal population in Sydney Harbour will grow. He says it’s an indicator of the improving health of the habitat, as none of this could have happened if there was nothing for the seals to eat. “It points to the fact that it is a recovering ecosystem,” he says.

It’s a recovery that benefits not only those seals in the harbour but humans too. Petrina Nelson, a planner with Canada Bay Council, which fronts the upper reaches of the harbour, says the council worked hard to get approval for its new harbour pool at Bayview Park, Concord, liaising with bodies including the Environment Protection Authority, Sydney Water and the University of NSW to ensure it would be safe for people to swim there. The process took years. “But we got there,” she says. More pools are planned up and down the harbour, alongside projects to improve the quality of the water that feeds into the Parramatta River and the harbour. “It’s pretty amazing,” she says. “I take my kids down to the baths at Chiswick and it’s wonderful. We have a fair bit of work to do convincing people that it is actually safe to swim, but it is. With the Bayview Park pool opening [due on November 13] there should be a massive celebration.”

Professor Emma Johnston says that because Sydney Harbour is a drowned river valley it is an incredibly complex ecosystem with a great range of depths, lots of rocky shores, soft sediments and little nooks and crannies. It has almost 600 species of fish, more than double the number of fish species in the UK. “It is one of the most biologically diverse harbours in the world,” she says, adding that it needs to be recognised for this ecological value, as much as for its beauty. There are some 5000 recreational boats moored on the harbour, which Johnston reckons is far too many. When Pat McDonough showed me a photograph of the harbour from her childhood, there were none. “We still haven’t got everyone to transfer over to seagrass-friendly moorings, which means that these boats swing around and it creates this great halo where the seagrass can’t live,” Johnston says.

Johnson says that with more extreme weather due to climate change, more work needs to be done to ensure that sewage doesn’t end up in the harbour after a deluge. “With rainfall becoming more intense, it overwhelms the sewage system,” she says. “We also need to have a plan for rising sea levels and what is the most ecologically friendly way to deal with that.” There should also be widespread plantings to restore salt marsh and mangrove habitats. “We have something truly unique in Sydney harbour,” she says, and it needs to be treated with great respect.

Pat McDonough would agree. “I feel blessed that it has been part of my life,” she says. “Every time I get out of the water I just feel wonderful. I’ve been catching ferries all my life, but still, every time I get on one I get excited. I never get tired of looking at it.” She’s excited, too, that a new generation of kids will get to experience the splendour of the harbour, frolicking in those new baths.

Greg Bearup is a feature writer at The Weekend Australian Magazine and was previously The Australian's South Asia Correspondent. He has been a journalist for more than thirty years having worked at The Armidale Express, The Inverell Times, The Newcastle Herald, The Sydney Morning Herald and was at Good Weekend Magazine before moving to The Weekend Australian Magazine in 2012. He is a three-time winner of the Walkley Award, and has written two books, Adventures in Caravanastan and Exit Wounds, written with Major General John Cantwell. He is also the creator of the hit podcast, Who The Hell is Hamish?

Add your comment to this story

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout