A doctor’s deeply personal plea to fix the crisis at the heart of the medical profession

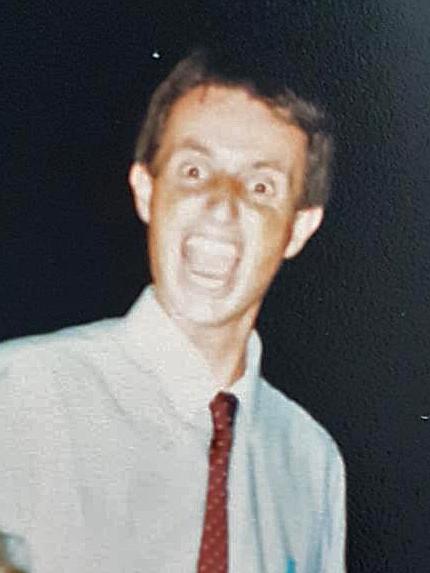

This is the place where a young doctor once came close to taking his own life. Now at the peak of his profession, he has this advice for those starting out.

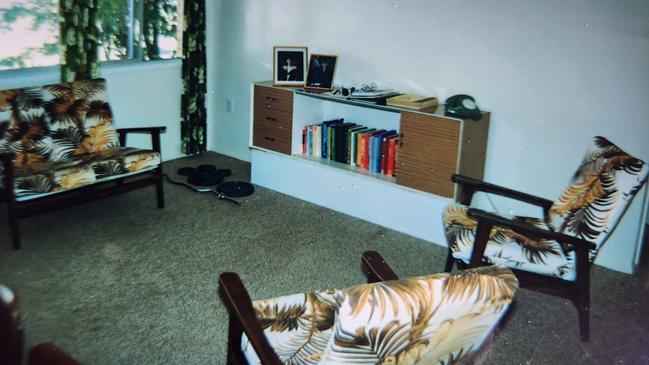

It was hardly a salubrious setting for what was almost the final day of my life. A sparsely furnished tiny brick box of a flat, oppressively warm even at night, an easy walk from the Rockhampton Base Hospital where I worked as a junior doctor. I had carefully laid out a large sheet of black plastic atop the cheap acrylic carpet, the kind of plastic you place at the bottom of a lovingly tended garden bed. In the central Queensland humidity, I didn’t want my decomposing body to make a mess. In my mind, with my thoughts scrambled by overwhelming guilt, infected by a pervasive sense of failure that I carried alone like a toxic secret, I felt I had been a burden enough to others already.

A few days earlier a man had died in my care. A local man, a father and grandfather, someone loved by his family. My decisions – or lack of them – had led directly to him losing his life. At that time in regional hospitals around the country, interns straight out of medical school (like I was) often worked as the only doctors on duty. A major hospital at night can be a lonely place. Senior clinicians could be consulted and called to come in during emergencies, but interns often made life-and-death decisions in the course of patient care. A terrible mix of my inexperience and fatigue had led directly to my patient’s death. The consequences of my actions came as a shattering blow, an arrow through my heart.

To this day medicine is not very good at responding to adverse events. It is difficult to prepare a young doctor on how to cope with a patient death that – despite whatever system failures might have contributed – they believe ultimately is their fault. It is the risk and reward calculus of medicine. The rewards of a lifetime in medical practice can be extraordinary, but the risk that error or miscalculation can result in harm or death is ever-present. When that happens to a young doctor, there can be a sense that the system piles blame on top of you, amplifying the already overwhelming feelings of guilt. For me as a young doctor, it was a burden too great to carry.

In my Rockhampton apartment, as evening fell, I put a cannula in my vein – not an easy undertaking one-handed. I was preparing to feed insulin that I had taken from a hospital supply cupboard through an intravenous drip when there was an insistent rapping at my apartment door. The visit from a fellow junior doctor, which for 30 years I believed was a matter of chance, was in fact a matter of instinct. Colleagues had seen me take the insulin from the cupboard, and feared what I planned to do. They had interrupted me with seconds to spare.

When I first alluded to the story of my own near-suicide in the Medical Journal of Australia six years ago, I urged readers: “If you feel now the way I did 30 years ago, seek help and support as soon as you can.” Today, that advice remains just as true – yet I see now, with clarity, that seeking help is only part of the solution. A recent audit by the medical regulator found that 16 Australian practitioners it had placed under investigation took their own lives in a three-year period alone. Some of these doctors had self-referred to the regulator, suffering mental distress – and instead of receiving a plan and support to move out of the dark place they found themselves in, they were faced with delay and a dysfunctional system.

Seeking help is important but it is not enough. The system in which we work must take responsibility for the pressures it places on doctors, acknowledge the harms inflicted on many who seek to heal, and reform.

It alarms me that junior doctors continue to experience poor mental health, unsustainable pressure in their working conditions, bullying and appalling treatment by others working in the system, and kill themselves in numbers that are simply intolerable. After more than two years I will step down as Federal President of the Australian Medical Association, and it is not lost on me that I have taken a journey from feeling that my prospects as a doctor were so poor that death was preferable, to standing as one of the most visible doctors in the country.

I cannot change the system single-handedly, but as someone who has experienced the most profound feelings of inadequacy at the birth of my career, who faced a night so black it was only the luck of timing I survived it, and who was ultimately, unfathomably, gifted a professional life marked by wonder and renewal as an obstetrician, I want to issue a plea to young doctors to hang in there, reach out, and believe in the future. I also want to issue a plea to the system to not let them down.

In the decades since my life almost ended in a stifling Rockhampton cinderblock flat I have become immersed in medicine, sometimes almost to the exclusion of everything else. More than once since that night, medicine has extracted a heavy toll. Its demands, at times, have almost broken me. In the decades after my suicide attempt, I tied myself in knots trying to deal with the experience. Indeed, a GP from whom I sought care told me never to mention what had happened to anyone lest it ruin my career prospects and my reputation. Denial was my stock in trade. Although I thought about it a little each day, I told nobody else and believed it was a secret that should never be shared. It became a dark, black hole deep within me, drawing in the matter from my world and compressing it until it was gone.

I am now telling my story, because the burden of responsibility that so many doctors feel cannot be carried alone. I don’t want any other young doctor to feel they need to carry a secret like I did for 30 years. I don’t want any young doctor to ever feel as inadequate as I did, and I want our health system – which in far too many hospitals is characterised by blame, fear and oppression – to face up to its too often toxic culture. The ramifications for staff welfare are obvious, but it’s also a matter of patient safety.

It’s a tragedy to me that some junior doctors abandon the system, burned out and dispirited (or worse), and will never know the joys that may lie ahead. I have had the privilege literally of holding many lives in my hands, often of newborn babies and sometimes of their mothers. I have spent decades helping people dealing with every experience from the deepest grief to the highest exhilaration. I have learned about fear, about love, about when to ask for help. About caring and about the power of hope. I want every young doctor to hold on to hope.

When I was growing up in a small town in 1960s Queensland, no one in my family had ever been to university. My father trained as a carpenter and my mother was a ballerina. They ran a motel in citrus country in rural Queensland before we moved to Toowoomba, where my father began a wholesale fruit and vegetable transport business. One of the people we delivered to was a medical specialist we called Doc Stringer, whose home seemed to be a place of perpetual chaos and fun. He was a wonderful conversationalist, the owner of a fleet of old Mercedes, a fascinating and gregarious character. He encouraged me to be a doctor.

My school careers counsellor, Mr Bradley, was sceptical that I could get the marks necessary for acceptance to Queensland’s medical school. I was determined, though, and to the amazement of everyone I managed to reach the standards. I wish I could tell a story of breezy inevitability, but that was not the case for me. I had to give up almost everything except study and, still, just scraped enough marks.

The experience of moving to Brisbane, and the adjustment to university, was overwhelming. I failed key subjects and had the humiliation of sitting supplementary examinations. Most of my fellow medical students seemed to take study in their stride but I felt like I was standing before a sheer cliff. Over my career I have learned that fear does not have to be the enemy, though. Fear affects how we act, and recognising this can also help us care better for people in our lives.

Fear was something I learned a lot about soon after I left Rockhampton. To pay my way through the last years of medical school I had taken a scholarship with the Royal Australian Navy and become a Medical Officer (I would eventually go to the Gulf War as a doctor). During this time I completed the Army’s parachuting course – despite having an acute fear of heights. During the course, a large part of which involved jumping out of the back of C-130 Hercules transport planes at 1000 feet, I spent several weeks in a state of fearful panic. Prolonged fear has a profound effect on one’s physiology, and I could barely sleep or eat. But despite my paralysing fear, I did manage to complete the course and earn my parachute “wings”, much to my own amazement. It was the most physically and mentally challenging training I had ever undertaken. The experience gave me a deep and enduring respect for fear.

Ultimately, I devoted my professional career to pregnancy and birth. I often cared for people who were fearful. If a birth is complicated, and urgent action is required to save baby or mother, fear is often in the air. Fear is contagious. It can spread not only from mother to staff, but also in the other direction. The appearance of panicky staff can turn a dangerous situation into a completely out-of-control one. That is when bad things can happen and scar those involved – whether patient or carer – for life.

I found that I had a sixth sense about fear and could pick it in people, even if they were doing their best to hide it. This allowed me to articulate fear and raise it first. Sometimes it would be like our shared secret – many times I would explain that I, too, had experienced it. I could understand how fear changes people and distorts their decision-making.

Many doctors – especially those completing their specialist training – confront fear in themselves too. Something I have learned on my long journey through medicine is that love can overcome fear, yet rarely do we talk about this. Just as I have learned about the effects of fear, I never underestimate the power of love. In the same way that fear affects our perceptions and our decision-making, so too does love. I want junior doctors who are navigating the health system to understand just what love can do.

Almost a decade ago I received a call about a situation that would, over time, utterly transform my understanding of the effects of love. That call was from a colleague who worked interstate. He told me the story of a man who’d been killed in a motorcycle accident several years before. Reproductive tissue containing sperm was taken from his cold body 48 hours after his death, but his partner had struggled to obtain a court order on a weekend allowing the sperm to be retrieved. It had remained frozen ever since.

Overwhelmed with grief, as all of us would be if the love of our life was taken from us, she had worked through the courts to demonstrate that, had her partner survived the accident, their intention was to have a child together. It has been an incredible emotional and financial challenge. My colleague was calling to ask if I would be prepared to perform IVF treatment with the long-frozen sperm with a view to this man’s widow having a child. I was extremely dubious – taking sperm 48 hours after death had never been done, and nobody knew what the outcome would be. Yet I was intrigued, so I flew interstate to meet and speak with the woman seeking treatment.

She and I spent a morning talking over coffee near a suburban park. She told a story of love that was irresistible to me. Of plans for a life together, of their commitment to each other, of their wish for a family. By lunchtime I had been won over and wanted to help, to take the journey with her. This was a love story for the ages. Incredibly, her eggs were fertilised and we were able to achieve a healthy pregnancy using the long-frozen sperm. Over the course of the pregnancy I kept in close contact both with her and her interstate obstetrician. A healthy child was born and I was so overwhelmed by the outcome that I flew over to see the new mother and baby. To this day, and under close surveillance, her child appears to be healthy and normal in every way.

Love is perhaps the most powerful force in decision-making. We’ve all done crazy things for love, and I’ve had the privilege to play a very small part in a love story for the ages. When young doctors feel overwhelmed, or struggle with dark thoughts, I want them to look towards love and its power to heal.

At the time I tried to fill my body with insulin and end my life, I saw no hope. I know that many other people have reached this point. I now never underestimate the power of hope. Being given hope can reshape the experience of illness or injury, for patients and everyone around them. It was something I had lost as a new doctor – and something that took a long time to regain after my suicide attempt.

I am not the only doctor who has attempted suicide. I have had close friends take their own lives, and the data tells us that the suicide rate among doctors is 34 per cent higher than the community more broadly. For female doctors, the suicide rate increased almost five-fold between 2006 and 2017, according to a study published in 2023. Surveys of young Australian doctors reveal that half of them report high levels of emotional distress.

Understanding this and offering hope and support, particularly to young doctors, should be a priority not only for my profession but for those who control and regulate medical practice. The feeling of being overwhelmed, particularly when things go wrong for our patients, can be terrible.

As I have become older, the temptation to sidestep difficult problems when the going gets tough has not gone away. As a doctor, though, things are not so easy. A recent case demonstrated powerfully that patients depend on you – absolutely – not to take away hope.

I saw a patient who was pregnant for the second time. Her first baby had been born by caesarean section, and all had gone well. In this pregnancy, however, there was a major problem. It was the pregnancy complication obstetricians fear the most. The baby’s placenta had implanted low and was growing through the scar of the previous caesarean and into my patient’s bladder. This complication – given the horrifying name “morbidly adherent placenta” – is dangerous to both mother and baby.

I had a series of frightening discussions with the patient and her husband as their toddler played in the room.

“Just how serious is the situation?” they asked. About as serious as it gets.

“Could I die?” she asked. Yes.

The patient and her husband shared anxious looks but she told me: “Well – we trust you and are glad to be in your hands.”

I have been a surgeon for over 30 years and spend a lot of time performing difficult surgery for conditions such as endometriosis and large tumours. I knew that the surgery required to safely deliver this baby, and to prevent the woman bleeding to death, would be difficult and complex.

As the baby’s birth day approached I felt more and more anxious; I would lie in bed at night, unable to sleep, playing out the birth in my head and fretting about leaving the baby motherless, the father a widower.

I had assembled a very experienced team to help me: vascular and urological surgeons, a top-flight anaesthetist, an intensive care team. The baby was delivered early in the morning, healthy and well, and we set about dealing with removing placental tissue that had invaded widely in the mother’s pelvis. The bleeding was extraordinary – overwhelming for us. We worked at the peak of our skills for hours. By late morning, I had a very grim feeling that we had no hope. The blood vessels were so large, so widespread, that controlling things would not be possible. It was a horrifying feeling. But we packed her abdomen with sponges and caught our breath. As overwhelming as the situation felt, we were not going to give up.

Gradually, we began to gain control. By the time she was wheeled to the waiting ICU bed we estimated her blood loss at 12 litres. Yet she recovered quickly, without complication, and went home with her baby. Rarely have I been so gratified by a result. The family – mum, dad and two children – moved interstate soon afterwards. I received a message on the child’s first birthday: a photo of the whole family, smiling and happy in their new home. It was awe-inspiring. Never give up hope.

The pandemic wreaked havoc with ourhealth system, and a pervasive sense has taken hold that hospital administrators don’t care about their workforce. Wage-theft class actions reveal that hundreds of millions of dollars in fairly-earned wages were never paid to junior doctors, who have been expected to work excessive overtime under great pressure for free.

This has compounded a burden that so many already shoulder. Bullying and harassment is commonplace. There is a crippling sense that nobody cares for the carers, in an era when many are at their most vulnerable. Yet shouldn’t the patients who seek care in our health system receive medical care from doctors who are at their peak? Fewer mistakes will be made, problems will be solved more efficiently, and the care will be better.

In the years after I tried to take my own life, I struggled with my emotions and my shame. So many people across Australian society – from every profession and vocation – have told me that they have experienced the same things. Doctors are famously secretive with their own health conditions, and for many years I was no different. I worried that referrals to my practice would dry up if word spread among colleagues that I was impaired by mental health conditions, or that I might try to kill myself again.

Help was available. Indeed, as a physician, I was literally surrounded by people who could help. But I’d decided it was better to bottle up these problems, to hide them and try to deal with them myself, than to admit what I was suffering. Recovery from the mental health problems of my early career was an arduous, draining and isolating process. If there is a single message that I want to pass on to anyone in such a dark place, it is that help is available. I had the incredible luck to have a second chance, to have colleagues intervene just at the critical moment.

It has been possible for me to build a career based around caring. To deal with fear and embrace love. To give hope to others. It was a difficult and steep path, and I don’t want to suggest for even a second that climbing from the depths has been easy or that I am unscarred. It is possible, though. For doctors who have spent years trying to master their craft, and so many hours memorising the body of knowledge that underpins everything they do, the burden of responsibility can be overwhelming. Working in a system that is overstretched and places so many demands on individuals, and yet is so unforgiving, can be a devastating experience.

Ultimately the system that provides our healthcare must value those who work in it. It is not enough to leave young doctors unsupported and adrift in a system that is so important to so many people. Patients have a right to expect that they are treated by people who are functioning at the highest level, not crushed by the demands of the system. Yet over the years since I first wrote of my experience, and made my plea that other young doctors do not suffer like I did, nothing of substance has happened. Hospitals and health systems seem to care less, and regulatory systems place burdens that are ever more stressful. Nobody takes responsibility.

I was more lucky than I could ever have imagined. I was saved by caring colleagues at the last moment. But it should not fall to colleagues to save their own. That is the responsibility of the systems that run our hospitals and medical training institutions. Unfortunately this message has not gotten through yet, despite the evidence of harms the system inflicts. Each life lost is a tragedy that further diminishes our system. I should know. b

Lifeline 13 11 14; beyondblue.org.au;

samaritans.org.au

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout