2020: The year of living dangerously

As we emerge from the ashes of 2020, we look back on the grim milestones and hard-fought victories and ask: how has 2020 changed us?

You sit, weary, the television news drifting to you from the other room, and simply close your eyes. Record November temperatures across Australia. Sixty-two bush and grass fires in NSW. Fraser Island ablaze off the Queensland coast. Almost 60 towns across Australia – from Andamooka in South Australia’s far north to Broken Hill in outback NSW to Devonport in northern Tasmania – sweltering through record-breaking temperatures. Then those words and phrases that make you wince. Advice. Watch and Act. Emergency Warning.

You don’t need to check your mobile phone for the Fires Near Me app that you downloaded at precisely this time last year. It and its terrifying graphics are still there. The tilted squares with the flame symbol in the middle. The chilling statuses – under control, out of control – that were branded on your brain last summer. You feel exhausted before the holiday season begins. The world has been tipped up on one of its points, like those bushfire flame symbols.

If 2020 has a theme, it is mortality. This pall of death over the world and your country and then where you live right down to the supermarket you shop in, your neighbours and you seeing the shadowy shape of a figure through the frosted glass of the front door and wondering: Is this person infected, and if I turn that handle, could I too be infected with Covid-19?

And while life as you once knew it is slowly seeping back, it’s returning in fragments and ghostly outlines, when it’s solid footing you’ve been looking for all year. Not bits and apparitions. Right now you’re one leg in and one out. Is it over? Is it safe? Can we come out now?

You’ve become suspicious. Wary. Alert to clusters of other human beings, the myriad surfaces you have to touch on any given day; elevator buttons, petrol pump handles, takeaway coffee cups, pizza boxes, even letters in the mailbox. You hear someone sneeze and you flinch.

This is what the year has done to you. You’re suspicious. Even superstitious. You’ve taken to the internet to confirm your new superstitions and search for the meaning of 2020 in the Chinese zodiac and learn that this has been the Year of the Metal Rat. One definition reads: “The year 2020 is quite challenging, especially health-wise, but also financially, with obstacles, impediments, and unpredictable situations, which will mainly occur during the first half of the year.” And there it is. “This situation is caused by the negative energy of the annual Flying Star Five, the star of destruction and disasters, which will have a strong influence during the Metal Rat year.”

Flying Star Five is the Bad Luck star. You already knew that. But how could you have even guessed, this time last year, that your nation was about to go to war with an infectious disease, have its economy crippled, see its people confined to their homes, schools empty, cities a wasteland, state borders battening down the hatches?

The giant map of the country’s east coast you bought last year and taped to the wall beside the fridge is still hanging there, a little fly-specked and edge-frayed. It was this map that your wife and children gathered around, before the Year of the Metal Rat, and excitedly worked out the Christmas/New Year road trip that would take in friends in Sydney, and two sets of grandparents on the NSW South Coast and in Canberra, along with a smattering of aunts and uncles. A bad luck trip that started confidently but was ultimately turned back by the Black Summer.

Your children, inches taller, with one of them thrown into puberty since last year’s holiday plans, are talking of resurrecting the road trip. You hear the news of the bushfires from the other room. You hear a loose corner of that map flap against the white wall. And you keep your eyes closed, long after the news is over.

The evidence was already there in the dying days of 2019, the Year of the Earth Pig (full of joy… a year of friendship and love). Above our heads. Beneath our feet. But you didn’t see the big picture. It was like those annoying Magic Eye or autostereogram pictures that were a fad in the 1990s where, if you stared at patterns long enough, a three-dimensional mountain or a wizard or a prancing horse might push out towards you.

As 2019 came to a close you’d witnessed an endless string of spectacular red smoke-filled sunsets, some captured on your phone. Then, virtually overnight, the beach here in far northern NSW was carpeted with black leaves and charred branches, a southern current carrying the detritus quietly to shore, the wreckage of an unexplained catastrophe from somewhere else. Fragmentary portents for the strangest year of our lives.

Yes, there were fires in the Nightcap Range from Lismore right up to the Queensland border in the late months of 2019, but they were kilometres away, and you had already planned your very Australian Christmas, the biennial Yuletide migration south to see family. Despite the increasing haze, and the sun frequently appearing as some sort of luminescent coin moving across the sky, it was summer, and that meant hitting the road, rest room breaks off the highway and fast food. It meant ignoring the heat and children squabbling in the cramped car, the tangled sounds coming from several different devices at once, and focusing purely on a family Christmas and then Boxing Day cricket on the telly.

Sure, it was hot, extremely hot, week after week through November and into December. You saw the bushfire disaster footage on the nightly news. Small towns up and down the east coast ringed by fire. Families, whose homes had been destroyed, camping in local showgrounds, displaced refugees in this apocalypse. But it was difficult, if not impossible, to appreciate the scale.

Your teenage son became withdrawn and sullen. A few weeks earlier he’d marched with his fellow students to bring awareness to the dangers of climate change. Now, suddenly, it was upon him, and it felt like the world was going to end. The catastrophe seemed to go on for months, tsunamis of fire roaring through great swathes of bush.

Then two brave volunteer firefighters, and young fathers – Andrew O’Dwyer, 36, and Geoffrey Keaton, 32 – died in a fire truck rollover near the village of Buxton, in the ranges north-west of Wollongong. And Prime Minister Scott Morrison was in Hawaii, where the sun wasn’t a blazing disk in a smoky sky and black leaves weren’t washing up on the sands. Our leader raced home when news of his holiday caused national disquiet and said in a radio interview: “They know that, you know, I don’t hold a hose, mate, and I don’t sit in a control room. That’s the brave people who do that are doing that job. But I know that Australians would want me back at this time out of these fatalities. So I’ll happily come back and do that.”

On some days here in northern NSW, the smoke from Nightcap National Park and Mount Jerusalem National Park still scratched at the back of your throat, but against all reason and logic your family hit the highway, southbound, along with other cars filled to the gunnels with kids and pillows and laundry baskets full of gifts wrapped in shimmering paper. And over in Wuhan, China, some 7800km away to the north-west, dozens of people were being treated in hospital for a strange new type of pneumonia.

By the time you hit the outskirts of Sydney, on your way to relatives in the village of Kiama, and then across to Canberra for Christmas with more family, the skies are black with smoke and you have to pull over repeatedly to make way for fleets of fire trucks. This is a natural disaster no longer viewed on television; it is just over there, beyond the boiling glass of the car windows.

You belatedly realise you shouldn’t be here; you might be getting in the way of the serious business of saving lives. You check the Fires Near Me app on your phone and you’re shocked to see there is no longer any definition to the map of the east coast of Australia. It’s just a geometric cluster of diamond-shaped warning boxes filled with fire, and most are out of control. It’s as if the small screen in your hand is a tiny window into Hades.

You stop briefly in Kiama, check the fire map again and observe with alarm the blazes further south and south-west towards the nation’s capital. So you turn around and head back for home, a decision that gives you comfort until that journey too becomes this frantic race to beat more fires and the possible closure of the Pacific Highway.

Christmas is shelved. Welcome to the Black Summer. There is a literal pall over New Year. The bushfire death toll on the south coast of NSW has risen to seven. Another out-of-control blaze is heading towards the township of Eden, on the NSW South Coast and close to the border with Victoria. You’re home safely but you still feel the need to check that fire app every couple of hours.

The news is filled with devastating images of buildings razed, houses lost, families blasted from their lives and left with nothing, whole communities trapped and forced down to the beach and the arms of the Pacific Ocean. It is unfathomable.

You see so often on television this man named Shane Fitzsimmons, the NSW Rural Fire Service Commissioner, in his crisp white shirt and epaulettes that you accept him as some sort of kindly, caring uncle. Quiet. Listen to Uncle Shane. He’s about to speak. How tired he looks as the days, then weeks, go by.

And life, as it does, rolls on. Everything in this world is no longer predictable. Everything is larger than life. In NSW, 5.5m hectares and 2448 homes would be razed during the fires, despite more than 2500 firefighters at work on each shift. In the end, the bushfires burn almost 19m hectares across the nation. They destroy almost 6000 buildings and take 33 lives; an inquiry will later find more than 450 Australians died of smoke-related illnesses from the Black Summer. How did life just become a set of numbers too huge to understand?

School uniforms and books are purchased. You try to stick to routine but it’s difficult because everything is different. The nation has not been permitted to go quiet over the traditional holiday season, that delicious, semi-somnambulant period punctuated with cold leftover ham and mangoes. When the wheels of daily life slow to a barely perceptible tick, then steadily click faster towards the end of January.

Australia Day. That’s the national alarm clock. The wake-up call. It’s time to get back to work, to get things rolling again across our charred country. It comes one day after Victorian health authorities confirm that a man had flown from Wuhan, China, to Melbourne while infected with something called the novel coronavirus.

We’re assured that Australia has this thing firmly under control. Federal Health Minister Greg Hunt says: “Australia has world-class health systems with processes for the identification and treatment of cases, including isolation facilities in each state and territory. These processes have been activated. Our laboratories have developed testing processes for this novel coronavirus that can provide a level of certainty within a day.”

You go about your business. After what we’ve all been through with the heat and the fires, who has time to worry about a person who seems to have caught some weird new flu?

A huge fundraising concert for bushfire victims is held in Sydney. And in late February the country, already rattled by the bushfires, is shocked into silence by another fire – when a mother, Hannah Clarke, and her three young children are doused with petrol by her estranged husband, Rowan Baxter, and burnt to death in their car in suburban Brisbane. You shake your head in sorrow. This is the real, deadly virus circulating in our society: domestic violence against women, day in, day out, week after week. The Prime Minister wants to rethink our entire approach to tackling natural disasters such as bushfires – and you think, well, perhaps it’s time to completely rethink how we deal with violence against women as well.

But the nation, by and large, has recalibrated. We’re back in our rhythm. Temperatures are set to cool into the relief of autumn. Then, in an instant, we lose our splendid isolation. The benefits of the tyranny of distance disappear. The World Health Organisation has already declared the worldwide outbreak of Covid-19 a “public health emergency of international concern”. On March 1, Australia records its first death from the virus.

You learn that a 78-year-old man and his wife had been on board the Diamond Princess cruise ship before they and more than 160 other Australians were evacuated and flown home. He was admitted to Sir Charles Gairdner Hospital in Perth, where he passed away. How could a retired gentleman, enjoying a cruise, catch this strange disease and die? And what is this word, pandemic? Hadn’t it last been used a century earlier with the Spanish flu? It is suddenly everywhere, this word, insinuating itself into the language.

Then overnight there are no toilet rolls or boxes of pasta or packs of rice in the supermarkets. It’s as if other people have intuited an impending catastrophe way before the rest of us and are off busily and efficiently preparing for the end of the world while we wander about clueless, scratching our heads, a disorganised rabble, unable to see the predator on its way, the menacing three-dimensional picture hiding in the Magic Eye pattern.

Is this what they call survival of the fittest? What do they know that the rest of us don’t? What is coming for us?

Then you start seeing people walking around in powder blue face masks, and it’s like you’ve wandered into some giant convention of surgeons. And for the second time in the space of months, a second emergency app makes its home on your phone, alongside Fires Near Me, Angry Birds and Trivia Crack. This is a federal government app with information on the deadly Covid-19 virus.

What is coming for us is something that no living human being has ever experienced, and something the world hasn’t seen for a century. In early 2020, the majority of us view the coronavirus as some exotic disease. (They said it came from someone eating a bat? At a food market in China?) It seems as interesting, and as impactful to us, at the bottom of the world, as a political demonstration in Eastern Europe or a mass shooting in Ohio.

Soon after our first Covid fatality, Scott Morrison forms a National Cabinet to manage the pandemic. Then he orders travellers arriving in or returning to Australia to self-isolate for 14 days. Self-isolate: another phrase that suddenly enters our lexicon.

This government action seems like good, old-fashioned common sense. But on March 18 the screws tighten and we are given a glimpse of a new, foreign-looking future. No more non-essential indoor gatherings of more than 100 people. Must maintain a social distance of 1.5m. Must practise hand hygiene. Must only travel when it is necessary. Must not engage in panic buying of food and other supplies. Must. Must. Must.

Australia’s two major football codes – the NRL and the AFL – go into hibernation. NRL CEO Todd Greenberg makes the announcement that, for footy fans, is incomprehensible. “We’ve asked our players not to turn up to training tomorrow,” Greenberg says. “While I say it’s a tough day for the game, I know it’s a tough time for everyone across our community. All we can do as a sport is remain united and follow the expert advice to keep everyone safe. We look at returning as soon as it is safe to do so.” The AFL follows suit. There goes a substantial portion of the national conversation. Although, nobody’s talking about anything else but the virus.

The Morrison Government announces a $66bn stimulus package, following on from an earlier one of $17.6bn, designed to prop up the nation during this crisis. Where’s the money suddenly coming from, you ask yourself. And then you instantly answer your own question – who cares? So long as it works. You’re not thinking LNP, not ALP, not Greens or red or blue or brown. Do what you have to do to get us through this thing.

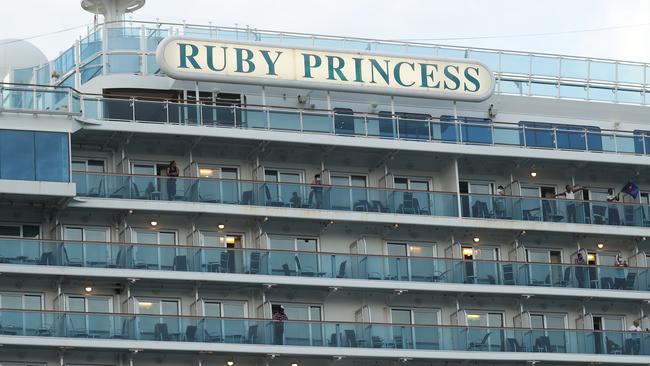

The Ruby Princess cruise ship docks in Sydney on March 19 and pours out more than 2700 passengers, despite a NSW health directive days before that required all cruise ship passengers arriving from another country to undergo 14 days of self-isolation. More than 900 of the ship’s passengers would later test positive for Covid-19. Twenty-eight would die.

On the same day that the Ruby Princess docked, Morrison announces that Australia is closing its borders to “all non-citizens and non-residents”, to take effect from 9pm on Friday, March 20. “We also strongly urge Australians looking to return home to do so as soon as possible,” Morrison says. “This follows our upgraded travel advice for all Australians not to travel overseas, at all.”

Then South Australia, Tasmania and Western Australia announce they will close their borders. On March 24, Queensland closes its border to NSW. That’s when you begin to accept that almost everything now is without precedent. “Extraordinary times call for extraordinary measures,” Premier Annastacia Palaszczuk declares.

The last time Queensland blocked its borders was just over a century earlier, during the great influenza pandemic of 1919. The descriptions of police guarding the Queensland/NSW border in the early months of 1919, and the scenes in 2020 at the M1 checkpoint between NSW and the Sunshine State, with its line of orange witches hats and fold-up sail cloths to shade the police on duty, are eerily similar. On March 4, 1919, a newspaper reported: “Four weeks have now passed since the Queensland border was closed, and success still marks the efforts to keep out pneumonic influenza... There are now 30 policemen engaged in guarding against the crossing of people from New South Wales into Queensland…” What hovers behind the old newspaper reports back then and the permit checkpoint now is a tangible sense of our collective vulnerability in the face of an invisible pathogen. At least until we get a vaccine.

At the border you wonder – we are of a generation that through fortune and fate has not suffered the rigours of war. Is this what our grandparents and great-grandparents talked about and lived through? The curfews against possible night-time bombing raids? The food rationing? The collective anxiety? The wholesale suspension of markers and ceremonies and events and competitions that once made up our lives? A situation so unique that even the burying of our dead has been disrupted?

Nooses are tightening everywhere. Pleasures denied. Routines shattered. Nerves frayed. Only five people can attend a wedding, and funerals are limited to a maximum of 10 people.

And suddenly, too, the impact of this unseen disease is before your eyes on the streets. In late March, soon after state governments announce that businesses including pubs, bars, restaurants and clubs will have to close, thousands of Australians suddenly queue outside Centrelink offices across the country. Many are seeking unemployment benefits for the first time.

It is getting difficult to keep up with the pace of life-changing events. It’s a cavalcade of distress and death and wholesale uncertainty. Then comes the tragedy of Newmarch House, a residential aged care home in western Sydney. On April 11, a staff member tests positive for Covid-19. By day five there are 15 confirmed cases in Newmarch House. By day 15, that leaps to 52. In the end, 37 residents and 34 staff will test positive for coronavirus. Of the 102 residents, 19 will die, with 17 of those deaths directly attributed to the disease. It is a devastating case study in how ruthless this disease is. Every Australian with elderly relatives swallows hard.

Then comes the strike to the heart of the national character: 2020 Anzac Day ceremonies and events are cancelled. “A small streamed/filmed ceremony involving officials at a state level may be acceptable,” the prime minister says in a statement. “There should be no marches.”

When does the fear begin to kick in? When does it hit home that life as we knew it has pretty much ended, and that to survive as individuals, as a community, as a country, we may have to totally defer to government authorities and their judgment? Probably around about now. Probably at the time of Anzac Day. Probably when we’re asked to contemplate, as we do every April 25, what it means to be Australian.

Who are we? What are our best qualities, and will we be able to apply them in this epidemiological battle? We’re practical. We’re fighters. We get on with the job. And we don’t ordinarily like figures of authority telling us what to do. But as Premier Palaszczuk points out, these are no ordinary times.

Billions of cash splashed about. Borders closed. People fined for not social distancing. There is a whiff of debate about responsible governments and human rights. Nine News political editor Chris Uhlmann writes: “Then the state border closures began and that proved more popular than free money. Australians were so happy to be carved back into colonies that the premiers found they could not go hard enough. There is now a competition for who can punt the reopening of border walls furthest into the long grass. The East German zeitgeist has now taken hold nationwide. Alas, the pandemic has, once again, revealed the natural authoritarian streak in Australian governments and how easily Australians fall into line.”

And the Australian Human Rights Commission issues a gentle warning. “Australia now has strict rules about when we can and can’t go out, what we can do and how many people we can see in person,” it says. “There’s strong community support for these restrictions. We are all in this together and most people have willingly made these sacrifices for the greater good of our whole community. But there’s also a hidden risk. Our willingness to accept sacrifice can leave us vulnerable to accepting greater restrictions on our freedom than are really needed to keep us safe… the strongest protection against extremism is to be crystal clear about what we stand for as a country.”

They can debate all they like. There is no need, or time, for debate when it comes to the safety of your family. You keep the kids home from school. You gather your little brood and explain to the best of your abilities what is going on, and what’s going to happen in the next few weeks and months (or years, who knows).

Your wife sets up a makeshift classroom where the kids can go each weekday to do their work. First bell at 8.30am. Final bell just after 3pm. That routine dissolves within 24 hours. You’re at home, all of you, on top of each other 24/7. You’ve sealed the family in from a deadly pathogen. You’re below deck on a ship in a storm. You have no idea how long this ride is going to last.

Then you remember one very important thing. Another great quality we possess as Australians is that we largely understand the notion of the collective good. Yes, we can be selfish. Yes, we can be opinionated, egotistical, loud, stubborn, boastful and sometimes unkind. But we know how to pull together. We know that if a family in Townsville does the right thing during the peak of this Covid madness, then that will, in the long run, benefit other families we don’t even know in Albury, or Hobart, or Victor Harbor, or Fremantle, or Blacktown, or Katherine. This we know. This we understand. The benefits, when required, of behaving in the interests of the collective good.

One of your children remarks about this notion: is that why we’re called the Commonwealth of Australia?

In late April, the deputy chief medical officer, Professor Paul Kelly, tells us: “Governments across the country have imposed tight restrictions on our daily lives to help stop the coronavirus from spreading and reduce people’s exposure to it. Restrictions have been imposed on the retail sector, and many facilities – for instance pubs, clubs, gyms and cinemas – are no longer permitted to open. Things that have been fundamental to our way of life are not currently available. Australians have adjusted amazingly with strong evidence of reduced foot traffic, public transport occupancy and many other measures that show we have got the message.”

Australians have adjusted. But in your own closed world you’re getting cabin fever. You have to strike out. You decide to visit your old hometown – Brisbane, just two hours up the highway – for the day. For a break. For a breather. Anything to see another vista.

You are in the so-called border bubble, so you print out a legitimate permit to cross into the Sunshine State. You’re excited. It’s like taking a trip overseas. You’re waved through without incident by a policeman beside one of the portable shade sails. Soon you’re slipping into the Brisbane CBD.

And there you walk into something extraordinary. An almost totally abandoned metropolis. In the main drag, the Queen Street Mall, a closed RM Williams store bears a sign in its shopfront window. It’s a deliciously Australian message of hope: “We have walked more than a few miles together and stood the test of time since 1932. With grit, tenacity and the Australian spirit, we will prevail.”

It’s rousing. A wartime message. Then you come across Chris. He is standing alone in Adelaide Street, preaching the word of God into a microphone attached to a small amp. Chris has a crucifix on his T-shirt. We need our faith now more than ever before, Chris tells nobody. Life goes up and down. Stay with God. His well-intentioned words fall under the wheels of the empty buses. Is he doing OK? Are people, or what people there are in the CBD, treating him well? “Last week a guy hit me,” Chris says. “Other guys had to stop him. There was no reason. This Monday, he came again, and spat on me. I don’t say anything. I don’t want to make him angry. Maybe he thinks I’m Chinese. You know, the virus. But I’m from South Korea. I’m just human, like you.”

Not far from where Chris is offering his epistles is King George Square and the City Hall building with its majestic clocktower. Since 1930, this has been the spiritual heart of Brisbane, its point of gathering, its maypole, but in the time of the plague it is not just empty but, without people, strangely forlorn. In front of the City Hall building sit two brass lions, their repose described as “lions couchant”, at rest with their noble heads raised. And generations of Brisbane children have rubbed their noses, stroked their cold manes, or hopped on their backs for a quick, motionless ride. When you touched the lions, you knew you were “in town”.

When the City Hall tower clock strikes 10am, in its deep and distinctive A-flat, it’s no longer a muted background pleasure, but in this empty city a booming vibration that bounces off nearby high-rise buildings and the largely treeless, paved surface of the square below. You drive home and can’t stop thinking about the bells of doom.

And still the virus flares and surges like the Black Summer fires, the embers of it picked up and deposited elsewhere, sparking another outbreak. This time in Melbourne, it flares through June, July and then come August it throws Victoria into a state of disaster. Melbourne is placed under curfew. People must stay at home from 8pm to 5am. They can exercise only for one hour a day, within a 5km radius of their home. Shopping is limited to one person per household per day. Masks are compulsory. Police are patrolling. And on and on.

By now you are, like everybody, fed up with everything. You are fatigued by the reality that there is no other news but the virus. Covid-19 itself has attacked and killed any other story that might be happening around you. Crime. Machiavellian politics. Scams. Great sporting achievements. Celebrity shenanigans. Concerts. Medical miracles. Stories that warm the heart and make you smile. This disease comes at you from every angle, fills your waking thoughts and, for some, slips into your dreams. It is a ruthless omnipresence.

It’s hard to look at maps and graphs of virus infections in other parts of the world. You have friends you love and care about who are stuck in the Northern Hemisphere and can’t get home. Someone knows someone knows someone who has died.

By the end of August, you realise that a sort of weight is pressing down on you and you can’t throw it off. A weight that has been building and building all the while, quietly and purposefully, as you’ve tried to juggle work and family and daily routine and attempted to navigate social distancing and potentially lethal contact points and worried about how all this is impacting your children and whether or not their core belief now, courtesy of the pandemic, is that if life is so fragile, is there really any point in living it to the full?

But in September, the advent of spring, Scott Morrison throws what appears to be a shaft of sunlight into the dark room that is the nation. He talks about how Australia has fared through the turbulence of the virus. “Our economy fell by 7 per cent,” he says. “Devastating, absolutely devastating. But compared to the rest of the world, it was one of the lowest falls of any developed country.

“And when you look at our health results, both on the case incidents in Australia of Covid and the upsetting number of deaths that we’ve had compared to overseas, I mean, I know a lot of people… talk about Sweden. Well, Sweden has had a bigger fall in their economy and they’ve had almost 20 times the number of deaths.”

Is this, paradoxically, a sign that we’ve turned the corner? When our leader begins comparing economic figures and coronavirus death tolls with other countries around the world? Not for poor Melburnians. They have been in isolation since July after Covid cases spiked and have experienced some of the toughest lockdown conditions anywhere in the world.

On October 26, though, Victoria records zero new cases and zero deaths statewide for the first time since early June. Premier Daniel Andrews announces a significant easing of restrictions to take effect over the coming weeks – cafes, bars, restaurants and hotels reopening with capacity limits, tattooists and beauticians resuming their services, a maximum of 10 people permitted to attend weddings, 20 mourners to attend funerals. And from November 8, the 25km travel limit in Melbourne is removed and gyms and fitness studios reopen with a maximum of 20 people per space, and one person per eight square metres. This is our present and our future. Maths. Equations. Measurements.

There are other calculations that, in the long run, must be considered. It’s easy to lose sight of the fact that our nation of 25m people has had only about 28,000 infections in total, at the time of going to press. Meanwhile, cases in the US recently passed a grim milestone of 15m.

But there is a singular event that says more than any politician, more than any chief medical officer, more than any medical statistics or graphs, about where we’re at as Australians in this global health crisis. It is about 8pm on Wednesday, November 18, at Suncorp Stadium in the suburb of Milton, Brisbane, where the third and final State of Origin rugby league match is about to kick off. It is an exceptionally clear night. The sun has just set.

An aerial shot reveals this majestic sporting stadium in a way that is both shocking and thrilling. The stadium is ablaze with gold and white light. The grass of the field is so green it makes your eyes hurt. You have seen this scene hundreds of times before but on this night it is profoundly different. The rectangular venue appears to be glowing, and for a moment it is no longer a massive steel and concrete structure, but an emerald cut diamond.

When you look closer, you notice that the stadium is holding 50,000 fans. Fans laughing and joking. Fans drinking beer and waving flags. Fans shoulder-to-shoulder in their seats. Forget the game itself, the metres gained, the tackles made, the team that conquered and lifted the shield. The pictures of these people in this arena captured what is believed to have been a world record sporting crowd since Covid had shut down global sport.

You can’t stop looking at the crowd. It is like a window into the way life used to be. It is hope.

Your children are again gathering around that map of Australia’s east coast, beside the fridge. At first it was whispers, then mutterings. Shall we give it another try, 12 months down the track? Should we resurrect that Christmas/New Year road trip?

You’re not sure how much they – indeed any of us – understand what aspects of Australian lives have been changed forever in 2020. All year there has been talk, even in your own circle, about how the pandemic has forced us to reassess what’s important in our lives. The big careers. The big houses. The big holidays. The big bank balance.

Has Covid-19 stripped everything back so radically that it has enabled us to view the vital essence of our existence? Will epiphany emerge from disaster? Psychologists, commentators, life coaches and innumerable pundits have been waxing lyrical about the good the human race can take from this global experience.

Tony Walter, Emeritus Professor at the Centre for Death and Society at the University of Bath in the UK, writes that our collective facing of mortality during the pandemic “offers an opportunity to rediscover truths about life”.

“Shared adversity can foster a sense of community and affinity with others that can be masked in normal times,” Walter believes. “The challenge is to sustain that after adversity ends.” He adds that this renewed connection has also seen the emergence of new forms of heroism “among frontline health workers, cleaners, delivery drivers, cashiers, refuse collectors and volunteers”.

Sydney University’s Associate Professor Adam Kamradt-Scott, an expert in global health security, says the pandemic has created an opportunity “to reconsider how we want our society to operate and what we value as a society”.

“I think humans have an innate desire to want to forget the trauma they’ve experienced – and this has been traumatic on a number of levels,” Kamradt-Scott says. “My fear is that in the process of trying to move past the trauma, we will forget the experience and the lessons of the pandemic.”

How will our work patterns, and our relationship to work, change? Early in the pandemic, Melbourne-based journalist Johanna Leggatt wrote: “At the very least, here is hoping that the pandemic spells the end of the developed world’s myopic focus on getting ahead, or growth for growth’s sake. Let it mark the death of our deification of work, of checking emails at 11pm, of Silicon Valley garble and its slavish obsession with disruption. Now that we are all working from home in our pyjamas let’s drop the soul-destroying pretence of robotic efficiency and find the humanity in what we do.”

And has the pandemic already changed the way we want to live? A recent survey shows that Australians are shunning big cities in this year of the plague and retreating to regional areas. Australian National University demographer Dr Liz Allen says the virus has “up-ended” the traditional trend of people moving to the big capital cities. “Covid is a major disrupter to the way we live our lives and how we view ourselves,” she says. “It won’t be a long-term trend. Once there is a solution to Covid then people will start returning to the cities, but whether they are the same people as those that left is another story.”

Melbourne psychologist and academic Dr Briony Towers, a research fellow at the Centre for Risk and Community Safety at RMIT University, who moved out of the city during the pandemic, reportedly says of Covid-19: “It has lifted the veil on how weak all of our social, economic and political systems really are – and, as a disaster researcher, I knew they were weak. I think Covid is causing existential crises for a lot of people.”

You start some preliminary packing for the Great Christmas/New Year Family Southern Road Trip Version 2. The car is booked in for a full service. The children’s grandmother in Kiama is sending them in the post actual menus for restaurants we all might go to when we come together for the first time since the start of the year.

You check the forecasts with the Bushfire and Natural Hazards CRC data. It says with La Niña underway in the Pacific, “the summer rainfall outlook appears favourable” for above average rain in NSW. But there is “always a risk” that if fires occur they will need to be monitored for escalation. The news, coming from the other room, now includes excited chatter about coronavirus vaccines.

Then your daughter announces her own good news. In the Chinese Zodiac, 2021 is the Year of the Ox. She reads from a website: “Having an honest nature, Oxes are known for diligence, dependability, strength and determination. These reflect traditional conservative characteristics. Oxes are strongly patriotic, have ideals and ambitions for life, and attach importance to family and work. Having great patience and a desire to make progress, Oxes can achieve their goals by consistent effort. They are not much influenced by others or the environment but persist in doing things according to their ideals and capabilities.”

The entire family quietly smiles – together, collectively, en masse – for the first time in an age. Yes, the Year of the Ox. We all like the sound of that.

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout