All aboard Kruger Shalati, the train that goes nowhere

Explore a remarkable new hotel in South Africa’s largest national park.

On the third day of safari Kruger National Park gave to me: three spotted leopards, two spiny porcupines and a lilac-breasted roller in a marula tree. The roller is a talisman, my favourite bird and the first creature to greet me on my post-lockdown return to a place in South Africa I have loved since childhood. It is waiting for me by the side of the road leading into the park from the airport at Skukuza. Head cocked and obsidian eyes shining, it pauses on the dead limb of the tree just long enough for me to snap its picture; then it ruffles its plumage, hovers momentarily, and vanishes in a flash of jewelled splendour. Come, follow me, it seems to be saying. Though I don’t know it yet, the roller’s welcome foretells a bounty I would never have predicted.

The leopards and porcupines will appear after nightfall, just as nature intended. Its rhythms have remained unfettered by the pandemic; while the world was in lockdown the inhabitants of this park – so vast it’s the size of a small country – have largely ranged free. As roads emptied of safari-goers, habituated wildlife may well have thought it was at last free of human incursion. Except, perhaps, for the leopards that happened upon a curious sight one day while crossing the Selati Bridge near Skukuza. A group of contractors were installing a train along the tracks of the long-abandoned structure.

“The contractors saw this leopard and two cubs – they were brand new, literally little, little babies walking along the bridge,” says Gavin Ferreira, operations manager at Kruger Shalati. “It was quite an amazing little thing. Except if you were a contractor.”

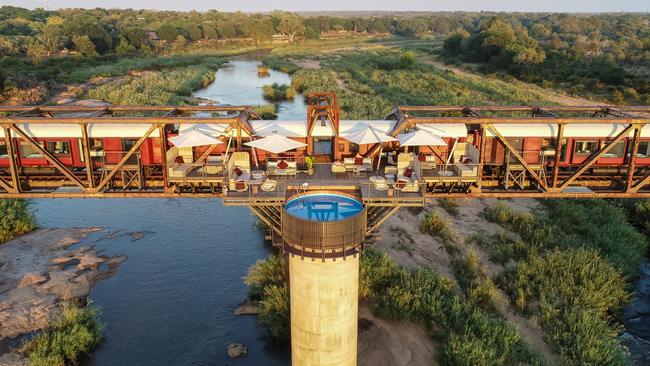

Such were the occupational hazards facing the developers of Kruger Shalati, the park’s singular new hotel, which opened against pandemic odds in December last year. I catch sight of it on the drive from the airport. I’m spellbound by the reincarnation of this heritage bridge strung high above the Sabie River. It’s reminiscent of a 1920s postcard with its oxidized steel trusses, timeworn stone pylons and the maroon-coloured South African Railways train that appears to have paused temporarily above the water.

It’s been nearly 50 years since a train last crossed these tracks. The line was built in the 1890s to connect Komatipoort with Tzaneen during the gold rush, but the era was short-lived and the disused line posed a threat to the park, according to Joop Stevens. The former head of tourism in the park and long-time South African National Parks employee, Stevens retired last year and is compiling a history of tourism here.

“You had this rail line running through the bush that didn’t ever really have a purpose,” he says.

In 1923, South African Railways introduced “Round in Nine”, a nine-day return sightseeing trip from Johannesburg to Lourenco Marques (now Maputo) in Mozambique. The train would overnight on the bridge en route, and the reserve’s first chief warden, James Stevenson-Hamilton, would entertain passengers around a bonfire with stories. An old photo depicts the gaiety – one person is playing a piano, somewhat improbably, in this bushveld scene.

“How [the piano] got there, I don’t know,” Stevens says. “But you can clearly see this person playing a piano there.”

This influx of merry tourists, the first of the park’s leisure visitors, had a dark side. Travellers would sometimes shoot game from the train, diesel emissions burgeoned with the increase in freight schedules, and oncoming locomotives posed a grave threat to wildlife. In 1973 a new line was built around the park and all the old tracks were removed, bar the 600m running across the Selati Bridge and either side.

Now the line’s heyday has been recaptured at Kruger Shalati. It is named for a female warrior (though history also references a local chief of that name), and built from a train reclaimed from a railway graveyard in the Free State, spectacularly refurbished and installed on the bridge in a 25-year concession deal with SANParks. The project took four years to complete, and those leopards crossing the bridge in broad daylight were the least of the team’s worries. The structure’s heritage status required a sensitive approach to reinforcement, installation of services such as plumbing and electricity, and construction of balconies, the central deck with its plunge pool and the walkway from which guests access their carriages. (An additional seven suites are located off-track in the Bridge House.)

The wheeling of the carriages on to the railway line and the settling of them into place posed the greatest headache. The refurbished carriages – comprising two suites each – were trucked individually from Johannesburg to Skukuza and placed with miraculous precision on a century-old bridge that expands and contracts throughout the day. Loose fittings were installed in situ, and the suspension was refined. The hotel can be dismantled, thereby protecting the bridge’s heritage.

“In essence we can wheel (the carriages) off if we wanted,” Ferreira says.

There are no leopards on the bridge as I make my way along the walkway to my carriage, but there are vervet monkeys galore. I close the door tightly behind me, a necessary step lest these cheeky fellows enter uninvited and help themselves to the contents of my minibar (yes, this can happen). While the train’s faithfully restored exterior recalls my childhood journeys in this country, its interior is a far cry from the cramped compartments I remember. An antechamber leads into a sumptuous room that appears to overflow the confines of the tracks beneath. Flecks of African colour – the plums and pinks and coppers of sunset – are picked out by flooding light. From the bed I can ogle a floor-to-ceiling vista of the bushveld, from the freestanding bathtub a direct view down into the river. At night, I will have to imagine the leopards prowling the riverbanks; but I will hear the buffalo grunting their complaints and the hyenas cackling in the distance.

The train’s central “dining carriage” is really a sleek bar opening on to a deck and that plunge pool dangling off its side. The water glows electric blue against the river splashing coffee-brown below. Hippos wallow down there between the grasses, and a crocodile sunbakes beside a pylon. Further down the line, beside the embankment at the entrance to the bridge, vervets eye off the dishes being served in the outdoor dining space. Some of their fellow residents feature on the menu: marinated ostrich fillet, warthog salami, braised kudu shank, crocodile carpaccio. An external game farm supplies these cuts; there are mainstream dishes for less adventurous eaters, along with plant-based options.

Those dishes spring to life on the game drives I take in an open Landcruiser with Kruger Shalati’s head ranger, Bonga Njajula. We spy a warthog digging in a culvert – “He’s doing some renovations after the rain, before the ladies come,” Njajula says – and a kudu with its elegantly striped nose and formidable spiralled horns. At dawn, I sip coffee spiked with Amarula liqueur and watch as the guinea grass glitters with dewdrops, and Jupiter and Venus and the scrim of new moon are erased by the slow seep of sunlight. At dusk, Njajula mixes gin and tonics as we wait for the potato bush to fill the night air with its scent of hot chips and the Southern Cross to emerge in its configuration of titanium full-stops.

There is no shortage of entertainment in this riverine part of the park: elephants play-fighting and giraffes browsing thorn trees; baboons surveying the world from the top of high koppies; vultures perched like grim reapers on sycamore figs; porcupines toddling like unwieldy pincushions through the bush; a pack of hyenas wearing “guilty as charged” expressions; and no fewer than three notoriously elusive leopards.

But all my Christmases come at once when we pull up in the dark behind a knot of safari vehicles gathered near an object on the road. There, in a celestial pool of light, is the creature most people wait a lifetime to see: a critically endangered pangolin. Two raisin eyes shine above an elongated snout; forearms are balled into little fists; the scales for which it is so highly prized click in a poignant metronome. On the most melancholy day of safari the Kruger National Park gave to me the world’s most trafficked animal, a pangolin. It is both omen and amulet, both a moribund species and a rousing inducement to defend this park’s long-fought conservation doctrine.

More to the story

Guests can take a short walk along the railway line to Kruger Station, a new dining precinct located on a historic platform between Kruger Shalati and Skukuza rest camp. The two developments have been a boon for an area crippled by unemployment; more than 60 per cent of employees now have jobs for the first time. Management has implemented an intensive training program that aims to empower the local workforce and redress some of the inequities wrought upon people dispossessed of ancestral lands now encompassed by the park.

In the know

Kruger Shalati is a short drive from Skukuza Airport in Kruger National Park. Carriage rooms are about $795 an adult per night. Children under 12 are not permitted on the bridge; they are welcome in rooms in the Bridge House, where rates start from about $618 an adult a night; family rates are available. Accommodation includes all meals, house wines, local-brand spirits and beers, two game drives daily in open safari vehicles and airport transfers.

Catherine Marshall was a guest of South African Tourism.

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout