Where to eat, stay and play in Tribeca in New York

Long one of New York’s toniest residential neighbourhoods, Tribeca is gaining a reputation among travellers with an eye for art, food and stellar lodgings like the Warren Street Hotel.

Wandering the Tribeca neighbourhood of Manhattan on Google Street View recently I came across a strange sort of anomaly. No matter the angle from which I approached it, an entire building seemed to be blotted out, or maybe absorbed by an extradimensional portal. A short search revealed the building to be the home of Taylor Swift, which she has had obscured on search engines, the better to protect her privacy. Such is the power and wealth of the residents of this “triangle below Canal Street” (Beyoncé and Jay-Z were engaged in their loft around the corner) that they can bend spacetime, or at least internet maps.

It hasn’t always been this way. In the 19th century, the sturdy brick and cast-iron buildings here were constructed as warehouses and factories for the then thriving cotton and textile industry. What had, in the Federalist period, been a marsh area north of the grand Trinity Church, subject to tidal floods from the Hudson River, was shored up and cobbled over for carts, and soon cars. The piers, markets, and series of bustling stalls extended from what is now Hudson Street – a far cry from where the shoreline is now – where a railway built by Cornelius Vanderbilt soon arrived to collect goods and fruit from the Caribbean at the docks in Tribeca. But this largely commercial area was famously quiet on the weekends when workers and merchants retired to their homes elsewhere in the city.

-

In the mid-20th century, as manufacturing left town, the neighbourhood fell fallow. Soon, the inevitable wave of artists came, drawn by the grand buildings with open spaces and vast windows providing walls of light. Around the same time that the disco set were making their way to Studio 54 in Midtown, the No Wave movement was taking shape in Tribeca, at Mudd Club, where artist Keith Haring curated shows and Jean-Michel Basquiat’s band Gray had a standing gig. Julian Schnabel lived upstairs.

In the late 1970s, the native New Yorker Robert De Niro came to Tribeca in search of a gym to train for his boxing film Raging Bull, and instead fell in love with the precinct and wound up moving in. “To me it was classic Lower Manhattan,” he said. In the 1980s, De Niro and producer Jane Rosenthal created Tribeca Productions to encourage filming in the city, setting up offices on Greenwich Street. “The neighbourhood was still pretty quiet then,” De Niro has said. “I had a few buildings around there that I wanted to make use of. I thought, ‘The one thing we must have is a restaurant’.” In 1990, he and his partners opened the Tribeca Grill, and soon the modern makings of the district began to take shape. In 2002, De Niro and Rosenthal helped to create the Tribeca film festival, in part as a stimulus package to the area so devastated on 9/11. And, in very short order, this neighbourhood of spacious lofts that had once been the haunts of artists soon became the most coveted real estate in the city.

But beyond the Greenwich Hotel, opened by De Niro in 2008, it hasn’t exactly been a hotbed of hospitality. Until now, perhaps. In February, the English designer and hotelier Kit Kemp and her company Firmdale Hotels opened the doors on the Warren Street Hotel. Like Firmdale’s Crosby Street Hotel in Manhattan’s SoHo, the 69-room Warren Street is animated by Kemp’s signature bright and eclectic designs, and popping full of artwork. The façade, a wall of glass latticed by aquamarine I-beams, plays in witty conversation with the steel and glass industrial neighbourhood around it. The roof is a brilliant canary yellow.

“We started before the pandemic, which slowed us down a bit,” Kemp says of beginning the project with her husband and Firmdale co-founder, Tim. “We felt our building had to bring back sunshine into our lives, so we decided on a summer blue sky [exterior] with a bright yellow hat sitting on top of the building. It brings that feeling of sunshine to Warren Street even before we open the front door.”

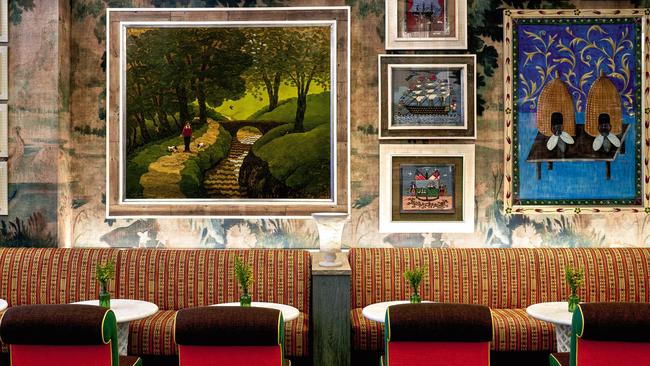

Immediately inside the hotel a horizontal totem in bronze and plaster, by English artist Gareth Devonald Smith, leads the energy and action through the lobby-level bar and restaurant where local families and professionals with offices nearby lunch or take aperitivos. Beyond the dining room, the Orangery, crowned with a massive skylight, is available for private dining and events.

“The defining feature of the hotel,” Kemp says, “is the garden terraces planted with grass, bulbs, trees, and bushes. You can sit in the bath and watch the flowers grow.” Or lap up the lofty urban views, including of One World Trade Center and the Woolworth Building, once the tallest skyscraper in the world. As if there weren’t enough to entertain the eye within. Kemp counts more than 800 works of art in the hotel, in the rooms, the cosy bar, and the restaurant – pieces she spent three years collecting, sourcing and commissioning.

“It suits the neighbourhood,” Kemp says now, a neighbourhood she has long admired for its “individual and eccentric shops cheek-by-jowl with art galleries and genius high-rise buildings”. In this culinary, cultural and architectural triangulation, it’s all about the mix. “I love that the area is rich in diversity but is still filled with mums and buggies strolling on the wide pavements at 3pm,” she says.

For the last generation or so, New York hotels have helped to shape the character of their surroundings – the Mercer in SoHo, the Bowery in the East Village – and have been both gathering points and community hubs. In the days after its opening, it seems as though the Warren Street Hotel has helped to fill that need for Tribeca. “I hope it will be loved by the neighbourhood,” Kemp says, looking towards the future of the property, “and by all the guests who come to stay. I hope it piques curiosity and brings a smile to our faces. I hope it becomes a hotel with a big personality – and, most of all, lots of heart.”

WHERE TO STAY

Warren Street Hotel: The 69-room lodging – the third New York property from Firmdale Hotels, after Crosby Street and the Whitby – brings the kaleidoscopic designs of Kit Kemp to Tribeca, and already it is being noticed. The brilliant, aquamarine exterior sets itself apart from, but in conversation with, the industrial and red-brick neighbourhood. Upstairs, in the guest rooms, Kemp’s signature oversized headboards, dress forms, and dazzling fabric wall coverings play with the cosy, clawfoot tubs and views of Manhattan’s famed skyline. Along with her daughters Willow and Minnie, both of whom work with her on the design team, Kemp collected and commissioned artworks to further animate the public spaces. And, less than two weeks after its opening, the bar and restaurant of the Warren Street Hotel was already buzzing, happily adopted by residents and office workers as a welcome new cantina and watering hole.

Hôtel Barrière Fouquet’s: The first hotel in the US by French hotel group Barrière, opened in 2022, is a wonderful mélange of Parisian chic with New York pep. Martin Brudnizki’s design in the rooms – pastel-pink accent walls and headboards, lacquered burl wood insets and brass finishings – against the famous watertowers of the cityscape outside might make you feel like you are in a movie directed by Sofia Coppola. The white tablecloths, lipstick-red upholstery and a slight Art Deco flair in the brasserie downstairs does nothing to dispel that fantasy.

Greenwich Hotel: Robert De Niro’s hotel is the nexus point of the area. The industrial-cum-Tuscan rustic décor of the public spaces, too, is the ultimate exemplar for what we think of as the “style” of Tribeca – how artists and De Niro himself might have lived in these great old industrial buildings and loft spaces throughout the latter half of the 20th century. The penthouse suite, though, by Belgian designer Axel Vervoordt and Japanese architect Tatsuro Miki, is of a different piece entirely, a Manhattan version of Vervoordt’s minimalist wabi-sabi style. And the restaurant on the lobby level, Locanda Verde, by chef Andrew Carmellini, has long been a city stalwart for approachable, delicious Tuscan food.

WHERE TO EAT

The Odeon: It’s hard to think of a restaurant that better articulates the aesthetic and culinary palate of New York right now – elegantly unfussy, with a little neon-lit noir glamour – than 44-year-old institution The Odeon, which was both cover star of and setting for a rather infamous scene in Jay McInerney’s Bright Lights, Big City. Essentially a corner diner dressed up with clubby booths, wood panelling, and Venetian blinds, The Odeon was from the time of its opening in 1980, as it is now, the greatest place for people-watching in the city, and a very fine spot for a Martini and steak frites or a hamburger.

Frenchette: After a long and lauded tenure as co-executive chefs within the Keith McNally empire, Riad Nasr and Lee Hanson partnered to open Frenchette in 2018 and it immediately became a new kind of downtown institution, winning three stars from The New York Times, and a James Beard Award for Best New Restaurant. The menu of elevated bistro classics – oysters, pâté, cassoulet, poulet roti – is as comforting as the natural wine list is good. And the room, with its swervy bentwood banquettes, is the kind that makes anyone in it feel cooler, more worldly.

Paros: New Yorkers love Greek food and have long been searching for a contemporary Aegean-style restaurant to match their affinities. Maybe that’s why Paros has been one of the hardest reservations in the city to nab since its opening this year. Occupying a signature Tribeca cast-iron building (complete with iron columns), Paros is airy, fresh and welcoming. The crisp white marble bar and cerulean-blue plates make perfect canvases for George and Nicholas Pagonis’s creative seafood dishes and Grecian cocktails.

Pepolino: Whether it’s the warmth of the ambience or the consistently amazing food, Pepolino manages to feel like both an indispensable New York restaurant, and the kind of comfortable home-style neighbourhood eatery we all wish we lived around the corner from. Exposed red-brick walls and plain, grooved farm tables, exceptional pastas, rack of lamb, beef tagliata, and a Tuscan-centric wine list have always made Pepolino a favourite for family dinner or date night.

Filé Gumbo Bar: Chef-owner Eric McCree was so enamoured with the slow-cooked Cajun-Creole fare of Louisiana that he replicated its zinging flavours at this sleek eatery. Expect tantalising takes on crayfish-topped bread, shrimp jambalaya, and fried chicken marinated in buttermilk and spices and served with red beans and rice. As its name suggest, the focus is gumbo, the boldly flavoured stew prepared to order, with a roux made from duck and chicken and filé (sassafras) powder an essential ingredient.

WHAT TO SEE

Anish Kapoor’s as-yet-untitled “mini-bean”: New Yorkers are notoriously tough critics – of everything but especially art. And maybe no work has drawn more attention recently than Kapoor’s mirrored mini-bean (a smaller version of his Cloud Gate sculpture in Chicago). Is it being squished by the equally conspicuous Jenga-like skyscraper by Herzog & de Meuron at 56 Leonard? Is it wriggling itself free? See for yourself and see yourself in it.

Galleries and the 9/11 Memorial: The eastern fringe of Tribeca is littered with art and design galleries, some of them up rickety stairs or in traditional white cubes (David Zwirner), occupying industrial spaces (Luhring Augustine and Artists Space), and even down a basement vault hatch (Theta) – making for the most varied, accessible, and efficient art crawl in the city. On the neighbourhood’s southern end is the astonishing National September 11 Memorial & Museum, on the former sites of the twin towers of the World Trade Center. From the twin, reflecting waterfall pools, titled Reflecting Absence, by architect Michael Arad and landscape architect Peter Walker, to the programing, and incredible collection of primary sources and artists’ responses to 9/11, the memorial and the museum make for a powerful and poignant tribute.

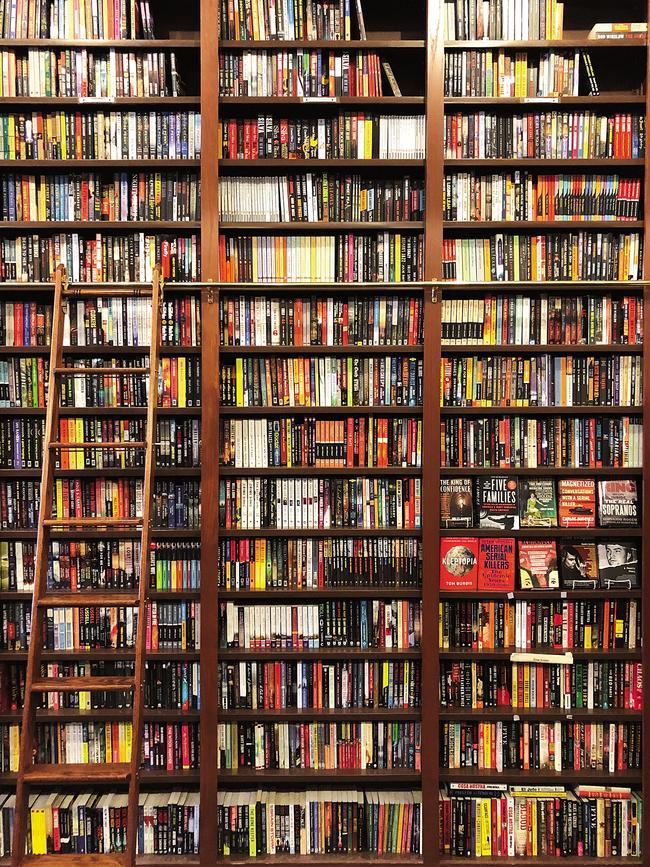

The Mysterious Bookshop: Opened in 1979, this glorious, creaking old shop of wooden bookcases piled high with plot-heavy fiction all the way to a cathedral ceiling is one of the greatest rooms, let alone bookshops in the city – and claims to be the world’s oldest specialising in mystery. Online, the bookshop also commissions original works by some of the best-known mystery writers in the world, but it is really within these walls, looking at first editions from Raymond Chandler, say, that readers, dreamers, and escapists can feel the magic of a mystery world tugging at them, and never want to let go.

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout