Where there’s a way

Start at the end of Portugal’s Camino

It feels strange and slightly wrong to be leaving Santiago de Compostela, one of the world’s most famous pilgrimage destinations, with a spring in our step and no blisters to boast of. It’s 8am and the square in front of the Galician city’s magnificent Romanesque cathedral is teeming with pilgrims who have spent weeks walking here along routes that have been trodden since the tomb of St James was discovered on this site in the Middle Ages. They enter the city from all directions, but we are walking the only trail to start in Santiago, a route that pre-dates Christianity and heads out of the city to the sea.

The Camino de Fisterra is an ancient 100km way that passes through quiet villages and oak forests and along mountain paths before reaching the sea at Fisterra, or Finisterra (the end of the world), as the Romans named the most westerly point of their empire.

Even before, it was a significant spot for pagans who travelled there to witness the sun “die” as it dropped into the sea. For them, this was more than somewhere to see an awe-inspiring sunset.

It was where the worlds of the living and the dead began to merge, where prayers and offerings were made to ensure the sun’s rebirth and benevolence. It was also believed to be the final destination of a route marked in the sky by the Milky Way.

I am walking this way with my teenage daughter, who will soon leave home for university, and a friend.

As we stroll out of the city into the surrounding hills, we look back on the cathedral’s spires, reaching up into the morning mist. We head through farmland and eucalyptus groves before eventually crossing a medieval bridge just before the town of Negreira, the region’s capital and alluded to by Ernest Hemingway in For Whom the Bell Tolls.

The Fisterra route is much quieter than the ways leading into Santiago. Most pilgrims end their journeys there, although some walk the extra four days to Fisterra or Muxia, further north on the Costa da Morte (coast of death), which earned its name because of the number of ships wrecked there by the stormy Atlantic waters.

We meet a group from Ireland who have already walked 790km from Saint-Jean-Pied-de-Port in France, but then reached Santiago and thought, “Why not go the extra mile?”

The extra mile is a whimsical understatement, but having walked various other stretches of the Camino previously and witnessed the congestion and the hordes queueing to get into the cathedral, I can see the appeal of ending on a more peaceful, less crowded way.

The route, with its mix of ancient forests, mountain paths and sea, gives a distinct sense of its pagan past, and the links between the Earth and our survival on it are still very much in evidence. “Is that a chapel?” my daughter asks, pointing to a tiny building on stilts with a cross at either end. It is, in fact, one of the many grain stores, or horreos, that dominate this route.

For pilgrims heading towards Santiago, a key moment is their first sighting of the cathedral, while on this route it’s seeing the sea. We glimpse it on our third day as we head down a mountain path towards the fishing village of Cee, a moment that also allows us the pleasure of being able to say, “Can you see the sea at Cee? Si!”

Religion, maritime traditions and pagan beliefs mix in the folklore of Fisterra and Costa da Morte. Shortly before we reach Cee, the route splits at the top of a hill, where two signposts, marked with the emblematic scallop shell of St James, send walkers in different directions, to either Fisterra or Muxia, where legend has it that a large rocking stone was the “stone boat” that carried the Virgin Mary to Galicia to visit St James.

Others claim it is just one of many stones worshipped along the Costa da Morte since pre-Christian times, when healing and storm-predicting powers were believed to derive from them.

We take the path to Fisterra, heading down to the sea past several small villages and along an undulating path, before it descends to the vast sandy sweep of Langosteira beach, where pilgrims have stopped to bathe since the Middle Ages, purifying themselves before the final few kilometres.

The water is Atlantic cold, but we manage a quick plunge before continuing to the town of Fisterra, passing through the Plaza de Ara Solis, the site of the altar to the sun (although there are no remains), believed to have been built by the Phoenicians or Celtic tribes

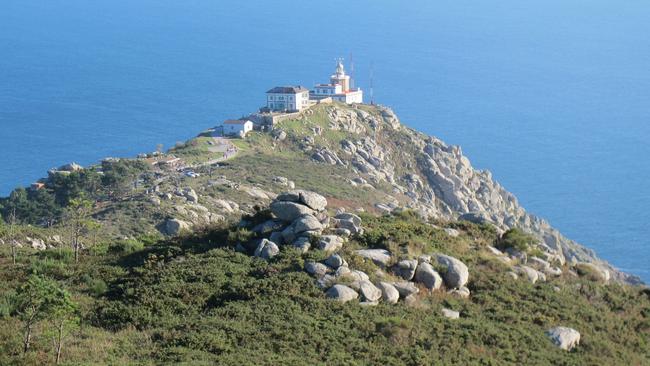

The cape is a few kilometres farther on, and here the end of the world is marked first by a milestone on which the figure is zero, then by a lighthouse, then by a stone cross perched on the rocks beyond, and finally just by the rocks beside the sea.

Latter-day pilgrims used to burn their clothes and walking boots here, but these days it’s frowned upon and it is enough simply to participate in the other Fisterra tradition — watching the sunset.

We watch and try to imagine what it must have been like for Celts or Phoenicians who believed that this was the end of their world, witnessing the sun deity slip into the sea and die before its rebirth the next day.

Whatever powerful emotions that must have evoked, we have our own. As we look across the vast glistening expanse of ocean, with its broad red stroke of sunset slowly spreading, my daughter muses on her forthcoming time at university.

For me, this walk with her to the end of the Earth marks the conclusion of a chapter in our lives; for her, looking out towards the horizon, it marks the start of a new one. I swallow hard as the sun disappears.

Lizzie Enfield was a guest of Camino Ways.

MORE TO THE STORY

SPAIN’S SECRET SIERRA DE AITANA

Close to the busy Costa Blanca, the limestone karst rock formations, spring-filled valleys and dramatic ridgelines of the Sierra de Aitana massif, which offer sparkling Mediterranean views, have been somewhat overlooked by visitors. With 300 days of sunshine a year it’s a great destination for off-season too.

LAKES OF SOUTHERN SWITZERLAND

Hiking in Switzerland doesn’t have to mean conquering 4000m peaks. A lovely hotel-to-hotel walking route through the forested foothills of Ticino, the region to the south of the Alps, is a low-altitude foray for pleasant strolling in the sun. Hiking between Lake Maggiore (pictured) and Lake Lugano, staying in a series of charming hotels, walkers on a self-guided break can enjoy the region’s distinctly Italian-leaning atmosphere and cuisine, with time for gallery visits and gelato stop-offs.

ST FRANCIS WAY, ITALY

The Italian equivalent of the Camino is the route inspired by the life of St Francis of Assisi, following an ancient Roman road between Florence and Rome. Hermitages, chapels and olive groves break up the kilometres as you pass through Tuscany, Umbria and the Apennines, refuelling with salami, truffle pasta and fabulous wines.

THE REAL ALGARVE, PORTUGAL

Promising to show off the authentic side of the tourist region, a holiday along the Algarve Way starting in Alcoutim takes in unspoilt villages and six walking routes that are an extension of the main GR13 walking trail.

THE TIMES