Watch the world slip by on a Rhone river cruise

A leisurely cruise from Lyon down to Provence strings together some of the most charming and edifying destinations in southern France.

The upside-down elephant, with four quadrupedal towers rising skywards from its mammoth Romano-Byzantine frame, is what locals call the Basilica of Notre-Dame de Fourvière, standing sentinel over Lyon on its hilltop. From this vantage point the city’s singular urbanscape is dramatically etched. The Rhône and the Saône, the two rivers that define Lyon, form a slim peninsula housing the central business district. On the east bank of the Rhône are many of the much-vaunted restaurants that bolster the city’s reputation as the gastronomic capital of France. The west bank of the Saône is crisscrossed by the labyrinthine narrow streets and hidden passageways of Renaissance-era Vieux Lyon.

Beyond the confluence of the rivers to the south, the Rhône continues its inexorable flow towards Provence, carving a path for the Mistral, the ferocious wind that blasts down the valley, mostly in winter and spring, bringing freezing temperatures, bending trees and blowing terracotta tiles off roofs. But you could say it blows hot and cold – clouds and mists are sent scurrying before it, clearing the way for the blue skies and sunny complexion the region is famous for, while it blow-dries the foliage of prized grapevines, protecting them from mildew and disease. It makes for a love-hate relationship among the Provençal people.

-

This is also the route I’m about to take on a week-long cruise down the mighty river with Viking on its Lyon and Provence itinerary, stringing together some of the most charming and edifying destinations in southern France. But before we depart on Viking Hermod we get to poke about a city that’s as rich in history as it is in culinary clout on a tour with an erudite guide. A small band of passengers, we head into the cobblestone streets of the Old Town to discover the traboules, hidden passageways between buildings, under houses and through courtyards created in medieval times to aid movement around the town. There are about two hundred here, though only a handful are still accessible, indicated by a sign next to a doorway.

Throughout the streets vivid silk scarves hang outside shops – silk is still produced in Lyon, though the weavers who once operated the Jacquard looms invented here have been replaced with automated looms. On Rue Saint-Jean, tourists crowd around the window of Pralus bakery, ogling the pâtisseries within. Here, in the ’50s, pastry chef August Pralus first created praluline, Lyon’s famed brioche studded with pink praline. One young boy barely waits to get out of the shop before tearing into a sugary confection.

-

Later, on board Hermod, an engaging lecture by a local historian recounts Lyon’s heroic role in the Résistance. Brave souls risked the menace of Klaus Barbie, the notorious Butcher of Lyon, to organise feats of sabotage, exchanging clandestine messages in the traboules and cafés, earning the sobriquet “the capital of Résistance” from General de Gaulle. While this propensity for rebelling isn’t exactly unique in France, Lyon set a precedent for protest when its silk weavers aired their grievances in 1831 by staging an uprising, thought to be the first in industrial Europe. In this instance resistance was futile.

On most days a cultural interlude is held in the lounge, be it a silkscreen demo or a nautical talk by Captain Claudy Cambron. Come evening guests gather here for drinks and program director Sam Kunkel’s discussion of the next day’s excursions – there’s at least one included tour with handpicked locals daily, along with optional tours (for an additional cost) – followed by live music after dinner.

Hermod is one of Viking’s fleet of sleek longships, low-slung vessels specially designed for river cruising. With capacity for just 190 guests, mostly well-travelled cruise fans, and 53 genial crew, new friends are easily made and the staff quickly learn your predilections. The interiors are bright and airy, with generous windows taking in the views, and exemplary Scandinavian styling throughout. My French balcony stateroom follows suit, the pale wood and clever design augmenting the compact space.

The following day, while we’re still docked in Lyon, most passengers take the opportunity to head to Beaujolais, its gently rolling hills scored by rows of low, goblet-shaped vines. In barely an hour we’re at Château de Varennes, a Beaujolais-Villages estate commanded by a fairytale castle with turreted towers that dates back to the 16th century. Like the whole region, gamay is king here – the drops we try are juicy and light-bodied with savoury notes – the same grape that powers the celebrated young Beaujolais nouveau released each November.

It’s white wine that eases me into lunch later, a chardonnay from the Mâcon region of Burgundy that nudges the top of Beaujolais. Chef Mousetafa Dieng devises menus divided into regional specialties and “classics” (the likes of steak and cheeseburgers are always available). Today the local line-up is a gorgeous salade Lyonnaise of frisée peppered with bacon and croûtons and topped with a poached egg and walnut vinaigrette, followed by pan-fried dorado with crushed potato and summery sauce vierge, and a light yet luscious cherry clafoutis.

Meals are served in the main restaurant on the middle deck, and on the Aquavit Terrace at the bow of the upper deck. Installed here at an outdoor table, G&T in hand, is a mesmerising way to spend an afternoon, taking in the river scene like a passing diorama, glimpsing villages on the tree-lined banks as they slip by, gliding under bridges – sometimes requiring the furniture on the top deck to be folded down – and negotiating the locks. The most thrilling is the Bollène Lock, where we inch down some 23 metres, the brutalist grey walls curving to meet above the gate like a proscenium arch.

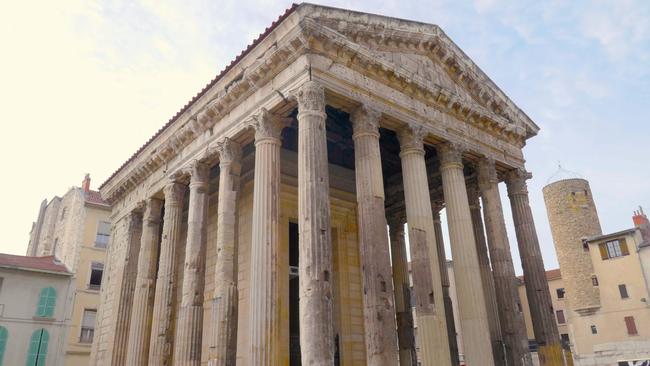

Our first stop is Vienne. Colonised by Julius Caesar during the Gallic wars, its Roman legacy is apparent in the wealth of ruins scattered throughout the town. Most notable, standing in what was the forum, is the Corinthian Temple of Augustus and Livia, the power couple of the time, built in the early 1st century AD. During our walk around the centre, we stumble upon a Pillory Square, a place where citizens were once publicly humiliated, known these days as social media.

The next day, after a whirlwind tour of Tournon, we’re scheduled to sail to Viviers. But, in a very French turn of events, we’re hemmed in by a riverboat whose captain has disappeared into town for a long lunch. Instead, our captain is eventually obliged to head straight to Arles. The city has significant monuments, not least its Roman amphitheatre, once the scene of chariot races and bloody gladiator battles, but it’s perhaps most famous as the one-time home of Vincent Van Gogh. Local pride in this heritage is impossible to miss. Van Gogh lived here for barely a couple of years, but it’s where he painted some of his most significant works, Starry Night and Café Terrace at Night among them. The yellow café remains, seemingly unchanged, but is closed after a spat with the tax department.

While some passengers elect to explore the city further, discovering other sights such as Frank Gehry’s crumpled Luma arts centre, a group of us head to the nearby Alpilles hills’ Valley of Hell for a spectacular encounter with Van Gogh’s legacy. Here cavernous quarries mined by the Romans for limestone are now the theatre for the Carrières des Lumières, spellbinding sound and light shows using around a hundred projectors to illuminate the cathedral-like spaces with vivid artworks. At the current show, From Vermeer to Van Gogh, viewers wander to shift perspective as images of Dutch masters dance on the walls, ceiling and ground. Flowers bloom, ships rock on stormy seas, feathers drift and sway alongside hovering cupids, all set to an eclectic soundtrack – from the Lakmé “Flower Duet” to “Pyramid Song” by Radiohead.

Back down to Earth, we circle upriver to Avignon, our final port. The fabled city was the seat of the papacy for 67 years in the 14th century, a period that produced two of its magnificent landmarks: the Gothic Palace of the Popes and the crenellated city walls (“They were built to keep the English out, but they don’t work any more,” quips one of our guides). A tour of the palace, through its warren of rooms embellished with frescoes of foliage, forests and hunting scenes, comes with a litany of fascinating fun facts: when dining, only the pope got a knife while everyone else ate with their fingers or spoons; the kitchen, a room with a conical ceiling rising 18 metres to form the chimney, could cook five bulls at once; guests were only allowed to leave the banquet room once all the gold and silverware had been counted.

The French popes shared a prodigious taste for wine – when bon vivant Clément VI was crowned it’s said that wine flowed in the city’s fountains for weeks. They favoured Burgundy, but also promoted the production of wine just north of Avignon in the now-acclaimed region of Châteauneuf-du-Pape, meaning “the pope’s new palace”. Pope John XXII, the second of the Avignon popes, had a castle built above the vineyards to use as a summer residence and under him the local wines were initially known as vin du pape. To this day the bottles of the predominantly GSM wines are embossed with a papal tiara above crossed keys. The castle on the hill is but a shell now – it was blown up by retreating Germans during World War II – albeit a shell with breathtaking views over the village and vines and down to the Rhône, a shimmering blue ribbon in the verdant landscape.

On our last evening we gather in the lounge for our farewell from the staff. Chef Mousetafa has a wake-up call: “Tomorrow you’ll be sitting at home on your sofa, waiting for someone to come at 7pm to tell you what’s for dinner, and it’s not going to happen.” Funny, but a sobering thought. The next day, before my transfer to Marseille airport, I head back into town. I might be facing the prospect of making my own food again, but there’s still time to track down a slice of pissaladière, the Provençale tart of caramelised onion, anchovies and olives (a personal obsession). As I sit on a bench, pissaladière secured, a young couple passes by. The guy looks over, smiles, and says, “Bon appétit.” In the south of France, lunch appreciation is de rigueur.

The writer travelled as a guest of Viking.

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout