WA’s wildfower season; Serengeti; Desert Weavers

For WA residents the onset of wildflower season signals it’s time to grab a camera and hit the road.

Western Australia may remain off limits for most of the population, but for locals the onset of wildflower season signals it’s time to grab a camera and hit the road. Blossoms have started appearing in the northern reaches of the Golden Outback, which covers more than 50 per cent of the state, from the rusty mound of Mount Augustus east of Carnarvon to the bleached beaches in the south. WA has more than 12,000 species of wildflower, including orchids, hakea, banksia, kangaroo paw, bottlebrush and everlastings, which carpet vast swathes of desert dirt in white, pink and yellow. More than 60 per cent of the varieties are found nowhere else on Earth. As the weather warms, the spectacle creeps south, culminating in flower shows at Ravensthorpe (September 7-16) and Esperance (September 22-26). The Road Trip Country website suggests six itineraries, each three to five days, for wildflower watchers. Take your pick from the wheatbelt area, the goldfields, Wave Rock, Fitzgerald River National Park, granite country northeast of Perth and along Indian Ocean Drive from the capital. The website also has a flower tracker on which spotters upload photos of blossoms as they appear around the state. At Mellenbye Station, about 430km north of Perth, guests can stay in self-contained accommodation and staff will help to find the popular wreath flowers. These circular clusters of delicate petals grow on the ground, as though tossed from a flower girl’s head at a country wedding.

roadtripcountry.com.au/wildflowers

PENNY HUNTER

View from here

SERENGETI

BBC Earth and streaming

It’s a jungle out there. Or, more specifically, almost 15,000sq km of tawny plains and grassland in northern Tanzania. This six-part miniseries focuses on generational hierarchies of “Africa’s most charismatic animals” in the Serengeti National Park and follows four seasons, shot by a crew of six cameramen and a wrangler of “specialist devices” such as drones, which give a broad sweep of aerial footage. It’s exquisite to the eye, although the saturated colours are unlike any I’ve seen in situ. Bit too much post-production, perhaps? Episode one sets the scene, focusing on families of lion, hyena, elephant and baboon. It’s initially odd that featured creatures are given first names, such as Kali, an ostracised lioness, and Zalika, a young hyena in training to lead her clan. Such anthropomorphising of wildlife is always tricky but series director John Downer claims the identities, all in Swahili language, are “appropriate to (the animals’) characters”. And the viewer’s investment in following their stories soon becomes personal, together with a heightened awareness of the constant dangers and battle for territory and sustenance. Kali has been shunned by her pride for bearing cubs to a male from another group; now she must fend for herself and four fluffy little ones. Zalika the hyena, her mother’s firstborn female, must learn how to take over a role as matriarch of the troop. The herd of elephant displays a formidable sisterhood and sense of family, with all members on high alert to protect a faltering newborn, his little trunk flopping about like a garden hose. The musical score occasionally grates, but there’s no denying the spectacle, and the narration by British actor John Boyega (Star Wars Episode VII: The Force Awakens) hits the right tone. One British reviewer criticised the “EastEnders storylines”. But even in the Serengeti, it’s all about life’s scripted opera of love, hope, betrayal and revenge. I am snared, hoof, line and sinker.

SUSAN KUROSAWA

Spend it

Tjanpi Desert Weavers is an indigenous-run social enterprise of the Ngaanyatjarra Pitjantjatjara Yankunytjatjara (NPY) Women’s Council, which runs a gallery in Alice Springs and an online shop that showcases a variety of individually created art pieces hand-woven from native desert grasses, seeds and feathers plus raffia, string and wool. “We make tjanpi work, sitting around with family and sharing stories, sometimes joking around … but always sharing stories,” says WA-based artist Jennifer Mitchell. Country, culture and community are at the heart of the artworks, which range from sturdy rainbow-coloured baskets fashioned out of harvested grasses (pictured; from $132) to beads and keyrings made from quandong seeds and painted gumnuts. But the most endearing works are the woven freestanding animal sculptures featuring a merry menagerie that includes camels, echidnas, lizards, desert dogs and wild birds. Each fibre-sculpted figure comes with a tag detailing its provenance and the artist’s name. Prices from $66 to $150.

SUSAN KUROSAWA

Book club

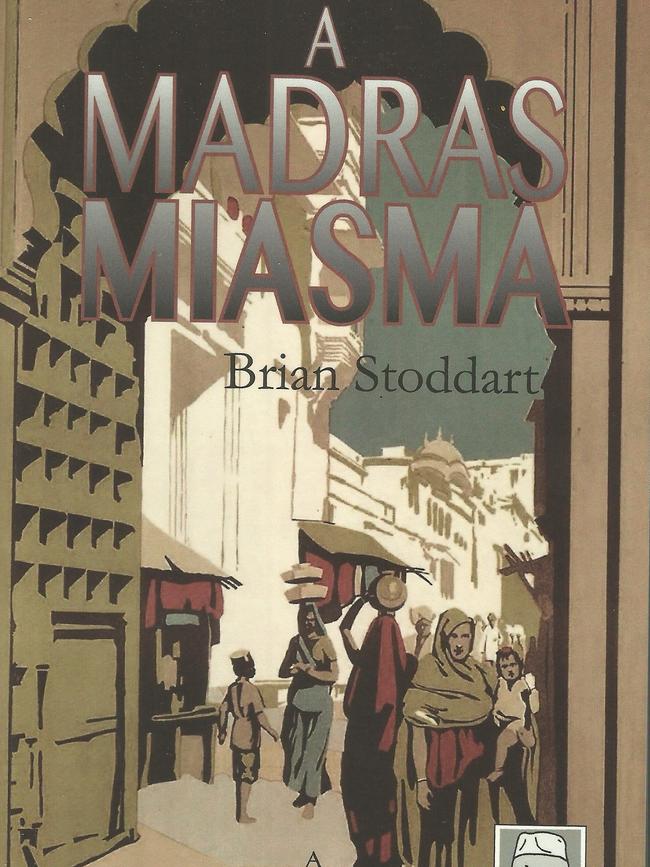

A MADRAS MIASMA

Brian Stoddart

A scholar in the history of modern India, and former vice-chancellor of Melbourne’s La Trobe University, Brian Stoddart has created an excellent and well-received series of crime novels starring the unimpeachable Superintendent Christian Jolyon Brenton Le Fanu of the Madras City Crime Unit. Set in the 1920s, two decades before India gained independence from British rule, Stoddart’s evocation of the colonial era is first-class, complete with political intrigue, racial tension between Hindu and Muslim factions, imperilled Indian royalty and the stirring winds of change. There are four in the linked series, and I suggest they be read in order so threads of relationships remain secure. A Madras Miasma was the 2015 debut, followed by The Pallampur Predicament, A Straits Settlement and A Greater God. Kicking off with A Madras Miasma, Le Fanu must solve the drugs-related death of a respectable young Englishwoman, ably assisted in his investigations by Sergeant Mohammad (“Habi”) Habibullah, a secular Muslim with a Hindu wife. Habi has converted to Christianity and likes to go home for a good lunch. He’s the perfect unflappable sidekick for Le Fanu, who’s started a secret relationship with his Anglo-Indian housekeeper after his wife’s return to England. The investigations of the two police chaps are forever in danger of being thwarted by the racist and vulgar Commissioner of Police, Arthur Jepson. But back to that corpse, which has been dumped in “the putrid shallows” of Madras’s Buckingham Canal. “She lay on her back, grotesquely angled, neck evidently broken …” Her veins show she’s a morphine user; she has engaged in recent sexual activity. Despite interference from the higher-ups, with their transparent toadying to the city’s captains of industry, the astute relationship of Le Fanu and Habi forms the backbone of the series and the reader is left in no doubt the pair will save the day. Visitors to what is now Chennai may recognise some of the Raj-era landmarks and Indo-Saracenic architecture that form the backdrop to the series, including the Madras High Court Building.

SUSAN KUROSAWA

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout