Wall Street Hotel New York City

This tranquil establishment is taking the Financial District back from the suits, and bringing a taste of Broome along with it.

The clues are everywhere if you look for them. A bronze oyster shell on the high-end liquor tray by the bed; the two mother-of-pearl shells framed on the bathroom wall; the adventurous seafood dishes and array of oysters (East Coast, West Coast, Long Island) in the hotel’s French restaurant, La Marchande. Even the view from my window, where I can see blue waters with high-speed ferries whipping back and forth, has a tropical air.

But I am in Lower Manhattan; in fact, the most “Manhattan” address possible, Wall Street. And the waterfront I’m glimpsing is New York Harbour, once the world’s busiest port. I have come to stay at the aptly named Wall Street Hotel, among the glass skyscrapers at the southern tip of what New Yorker Herman Melville, author of Moby Dick, called “the insular city of the Manhattoes, belted round by wharves as Indian isles by coral reefs”, adding archly that “commerce surrounds it with her surf”.

It’s not surprising the subtle artistic evocations of the southern hemisphere are everywhere. The hotel is owned by the Paspaley Australian pearling family and its interior design includes subtle nods to faraway Broome. It opened its doors last August, and has hit its stride as an anchor for the now-booming area. For travellers, it’s an alluring new base in a neighbourhood once desperately short of charm.

I should confess I have ventured into Lower Manhattan from my East Village apartment under protest. Of all the famous New York neighbourhoods, the Financial District has always seemed least appealing. When I moved to the city 25 years ago, I made a ritual visit to The Street, paying my respects at the Stock Exchange, taking the ferry from the Battery to the Statue of Liberty, and having an overpriced drink in the historic Fraunces Tavern, where George Washington once slept.

But its narrow roads teemed with harried office workers and were lined with grimy skyscrapers that blocked the sun. There were few decent restaurants or bars, no museums, no attractions. I rarely found reason to return.

All this began to change a little over a decade ago, when a more bohemian element began moving in to the forgotten warehouse spaces. The district even got its own real estate moniker, FiDi. The Beekman hotel, a former law office building that became one of the most beautiful renovated structures in the US, opened near City Hall, some adventurous eateries started luring diners, and an Irish cocktail lounge-pub in a historic building was voted the world’s best bar by Drinks International magazine.

Even so, when I heard the hotel had opened last year at No. 88, the belly of the beast, I felt some trepidation. Was there enough of a social life in an area synonymous with stockbrokers and money worship to justify staying there rather than, say, SoHo or Tribeca? Was there more to the neighbourhood than Gordon Gecko types?

And so I take the subway from East Village with a mission: I will use the hotel as a base to see if the “new” FiDi lives up to the hype. The moment I emerge on Broadway, it’s obvious change has been afoot. Directly above the subway steps is Trinity Church, one of the oldest places of worship in the city, which has been given a facelift that includes new stained-glass windows by contemporary British artist Thomas Denny. Things are looking up. I stroll down Wall Street for the first time in years. It’s now a pedestrian mall with massive security barriers and a huge police presence to foil any potential terrorist attacks. The Stock Exchange still looms like an ancient Greek temple, but since 9/11 it has been defended like Fort Knox. Visitors can’t get anywhere near it, let alone enter on tours.

The claustrophobic ambience eases when I spot The Wall Street Hotel, set in a stately 14-floor Beaux Arts edifice from 1901 called the Tontine Building, once owned by an import-export company that specialised in mother-of-pearl buttons and purchased some of its raw material from the Paspaleys Down Under. The family acquired it after the death in 1986 of Allan Gerdau, patriarch of a rival pearling business. The advantage of the hotel’s location is it’s only two blocks from the waterfront, which has undergone a major renovation since it took a beating from Hurricane Sandy in 2012. New York’s main public ferry hub is literally at the end of Wall Street, linking it to the remotest corners of Brooklyn, including Coney Island, for the price of a subway ride, $US2.75 ($4).

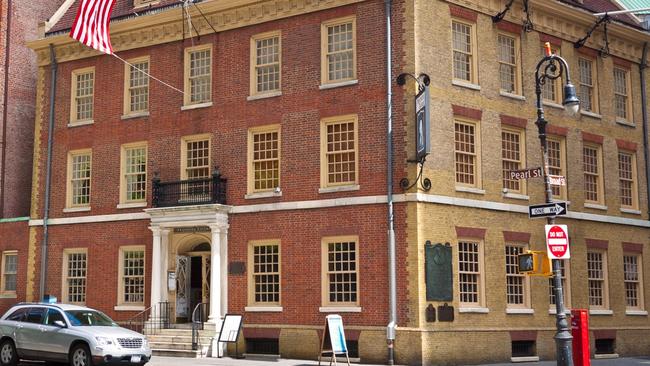

But first, the hotel. It stands at the corner of Wall and Pearl streets, so named back in the 1600s when the shore was encrusted with oysters (my first Paspaley clue). The lobby is elegant and chic, with splendid pearl jewellery for sale in softly lit cases (clue No. 2) but I am distracted by the attached cocktail bar, the Lounge on Pearl, a glamorous space filled with sumptuous armchairs, towering mirrors and a marble bar that demands the order of a martini, the obligatory libation of Wall Street brokers. Thus fortified, I’m ready for check-in. “Where have you come from today?” chirp the two hotel clerks in unison, with a sense of good cheer that defies my dour image of the district’s denizens. “The East Village – why you’re barely away from home.”

The hotel has 180 guestrooms and suites decorated in warm sand and blue (which, to me, evokes the beach) by Miami-based design company Rose Ink Workshop. Even the abstract prints on the walls and grey-blue carpet patterns conjure the movement of water. Also on display are Indigenous artworks from the APY Art Centre Collective and photos of Australia’s pearling heritage. I am assigned a corner Carnegie Suite on the fifth floor with views between the skyscrapers to the harbour. The name is an homage to 19th-century robber baron Andrew Carnegie, whose steel industry holdings made him one of the richest Americans in history. (On the plus side, he also founded the US system of public libraries to allow others to educate themselves and have a stab at wealth accumulation.) The Gilded Age scion Carnegie would surely have approved of the generous proportions of the room, the array of whiskeys on the sideboard and the porcelain bath with a view.

It’s getting dark, and dinner is in order. Until recently, the most famous restaurants in FiDi were old-school steakhouses like Delmonico’s, patronised largely by company men. Last year, Daniel Boulud’s elegant Le Gratin opened in The Beekman, offering a charming vision of the French belle epoque. Now The Wall Street Hotel has joined its ranks with an in-house fine-dining option, La Marchande, a modernist take on the classic French brasserie. Joined by a friend, I settle into a booth in a private niche and order a parade of delicacies, starting with three types of oyster with Champagne. This is followed by a stream of dishes that would have verged on science fiction in FiDi a few years ago, including steamed Dover sole with vermouth-lime butter (paired with sancerre) and grilled lobster with coconut sauce americaine (accompanied by a “vermouth flight”).

The next day, I’m ready to explore the waterfront promenade that begins two blocks away. The shoreline, where some of the oldest saloons in New York never reopened their doors after Hurricane Sandy, has been salvaged. The centrepiece is Pier 17, better known as the South Street Seaport, which New Yorkers long avoided as a cheesy tourist trap with a few historic boats docked by nefarious fast-food eateries. All that is ancient history. Late last year, celebrity chef Jean-Georges Vongerichten restored a key landmark, The Tin Building, a 1907 structure that housed the Fulton Fish Market before it moved to the Bronx in 2005. It is now a high-end gourmet food court with a lively, open-plan atmosphere.

I am heading to a more relaxed and gracious destination, upscale Italian restaurant Carne Mare, which opened in a gleaming contemporary structure at the end of the pier in 2021. As the name suggests, the focus is on classic steaks and creative seafood dishes such as roasted Maine sea scallops with celery root puree and Barolo jus. When the waiters hear my accent, they summon chef della cucina Brendan Scott, who hails from Brisbane and cut his teeth at award-winning Cha Cha Char before moving to London and New York. Small world.

With such culinary distractions, it’s easy to forget how rich in New York history FiDi is, partly because so much of the past has been buried under skyscrapers. This was where the Dutch founded the city as New Amsterdam in 1624. In fact, Wall Street was named after a fortress wall, built by African slaves to protect the winding warren of streets and cow trails in 1653. Even after the British took over the Dutch colony in 1664 and renamed it New York, the settlement barely extended beyond the wall for generations. The district remained the main port area of Manhattan well into the 19th century, its shore thick with wharves and crowded with masts and rigging.

Today, a few quixotic relics of the colonial era survive. A few blocks from the hotel runs the oldest paved laneway in New York, Stone St, lined with gravestone-shaped cobblestones known as “Belgian blocks”, which arrived from Europe as ships’ ballast. It’s also where pirate Captain Kidd’s mansion once stood. Nearby is the site of Lovelace’s Tavern, a bar owned by a British governor from 1670 to 1706, its foundations visible through glass set into the footpath.

To experience a living homage to the area’s raunchy maritime past, I head to legendary Irish cocktail bar and pub The Dead Rabbit, a slice of 19th-century lore straight out of Gangs of New York. It was opened in 2013 by two Belfast lads, Sean Muldoon and Jack McGarry on Water St, where (as the name suggests) harbour waves once lapped almost at the steps of the historic building. Here, thousands of Irish immigrants from Dublin and Derry would pour daily on to the wharves. The venue has since won almost every cocktail award in New York, and is regularly voted world’s best bar.

I climb wooden stairs past the Tap Room, where sawdust is scattered on the floor, to take a stool in the quiet, dimly lit parlour, where the bartender is chipping violently at an enormous ice cube with a metal pick. Soon, a complimentary whiskey punch welcome drink appears in a crockery tea cup. I examine by candlelight the cocktail menu, which is as thick as the Bible and includes a graphic novel introducing the pub’s patron saint, Irish ruffian-hero John Morrissey, who brawled his way up from poverty and died a New York senator in 1878.

To create their menu, Muldoon and McGarry consulted more than 50 American cocktail books from the late 1800s, starting with what is thought to be the world’s first, The Bar Tender’s Guide, written in 1862 by New Yorker Jerry Thomas. After experimenting with more than 1000 recipes, the pair honed their list to 72 cocktails with names such as Tween Deck, Lamb’s Wool and Stone Fence. As I knock back a plate of oysters with a Banker’s Punch, a delicious concoction made from three rums, port, raspberry cordial, lime juice, Orinoco bitters and fresh nutmeg, I imagine Herman Melville at the next stool regaling me with whaling stories. And that’s a vision of FiDi I could get behind.

In the know

The Wall Street Hotel has rooms from $US499 ($730) a night. Hotel restaurant La Marchande is open for dinner Tuesday to Saturday; lunch and breakfast daily. The Dead Rabbit’s Taproom opens daily from noon ’til late; the Parlor opens Tuesday to Saturday; 30 Water Street. Carne Mare, at Pier 17, is open seven days a week for dinner; Monday to Friday for lunch.

Tony Perrottet was a guest of The Wall Street Hotel.

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout