Uluru luxury resort Longitude 131 puts Indigenous art in the picture

Uluru and Kata Tjuta are the backdrop for a remarkable creative collaboration.

Pitjantjatjara woman Janet Tjitayi is placing dots of lemon yellow, white and earthy orange on a black canvas awash with sinuous lines and concentric circles. It’s painstaking work that requires precision and patience, commodities she seems to have in abundance. It’s also mesmerising to watch as she brings the Indigenous story of Piltati to life.

The tale concerns a pair of brothers whose wives wander off for too long and have to be lured back home by their cranky husbands. It features snakes, shapeshifting and waterholes and the ending is not entirely happy. Tjitayi, however, appears very happy to be making her art in the tranquil, airconditioned comfort of Longitude 131 while outside the Uluru furnace is firing up to 40C.

Along with her sister Umatji, Tjitayi has travelled to the luxury property in Australia’s red heart from Ernabella, an Aboriginal community of 500 people about three dusty hours’ drive away across the South Australia border. The township, a former mission, is home to the country’s oldest continuously running arts centre, in existence for 80 years.

Baillie Lodges, owner of Longitude 131, has hosted a regular artists-in-residence program with Ernabella for the past four years. It’s a collaboration that could be the definition of Pitjantjatjara term ngapartji-ngapartji, used to describe a mutually beneficial relationship.

The artists get to make their art and raise money for themselves, their families and the arts centre; in return, guests are afforded the opportunity to watch works take shape and engage in a cultural exchange that otherwise might not be possible.

Ideally, some will take home a canvas or one of the ceramic works for which Ernabella is renowned. Artists receive 60 per cent of the sale price of a work and the remainder goes to the arts centre to put towards materials, facilities and wages.

‘It’s an excellent income source for the community but also really good for the wellbeing and self-determination of Indigenous people’

This special relationship, fostered by Hayley and James Baillie, is writ large everywhere at Longitude 131. On the walls of the airy Dune House building and in each of the 16 fabric-swathed luxury tents are vibrant paintings that bring the all-important tjukurpa law and lore to life. In the circular Spa Kinara, designed like a traditional wiltja or shelter, spears made by Ernabella men are on display. Behind the Dune House bar, a wall is lined with specially commissioned tiles in a spinifex pattern made by the women. So central are ceramics to Ernabella’s output that the Baillies have contributed $150,000 over three years for a dedicated ceramicist to help the community develop their practice. In that time, the centre has raised $750,000 from sales of these items alone. Earlier this year the resort took delivery of its latest canvases and other works, valued at $25,000.

These are significant sums but the benefits extend well beyond the monetary.

“It’s an excellent income source for the community but also really good for the wellbeing and self-determination of Indigenous people,” says Mel George, who has co-managed the centre for three years, answering to an all-Aboriginal board.

George helps me chat with the Tjitayi sisters, using a mixture of English and Pitjantjatjara. For the pair, the week away offers respite from community life and family responsibilities plus a rare chance to experiment with their art. Janet has never painted the Piltati story before. Umatji has been inspired by a teaching from her grandfather to depict the honey grevillea, which traditionally is used to make a sweet cordial.

“It’s really good for the artists to get exposure like this and have time to work on their art and meet people and be treated really well, just like guests at 131,” says George. “That kind of stuff goes to issues of reconciliation. I also think many people don’t get a chance to meet an Indigenous person and they can here. This is providing a platform. They’re not dragged up here; this is a special thing [Ernabella] people love to do.”

On our way to Uluru, the vertical black brushstrokes of desert oaks are striped against the bright orange desert sand, and anthills congregate like standing stones

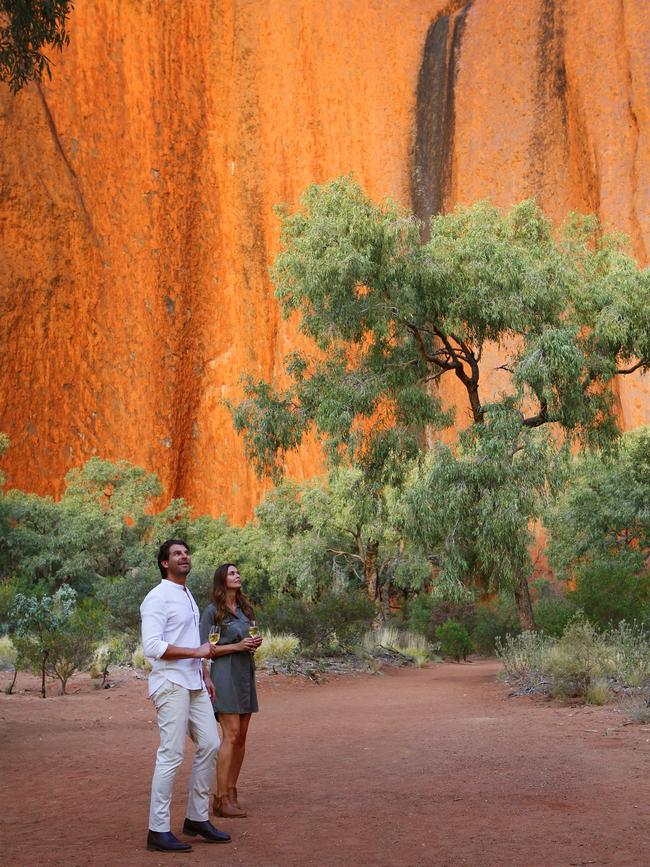

And it all takes place against Uluru, one of the world’s most spectacular backdrops. The ancient monolith looms on the horizon, shadows and sunlight playing across its surface through the day. It has been more than a year since the Anangu people succeeded in their long-running request to end climbing of the sacred rock. What a year it has been, with the Northern Territory and vulnerable Aboriginal communities shutting themselves away from the rest of the country, and the world, for months because of the COVID-19 pandemic. For a destination that normally attracts more than 250,000 visitors a year, how empty the place must have felt. Ben and Louise Lanyon, managers of Longitude 131, were able to retain some of their team and spent the hiatus performing maintenance before welcoming their first guests back at the end of August.

With more borders reopening, and Australians eager to explore their own back yard, visitor numbers are picking up and guests seem undeterred by summer’s unrelenting heat. By all reports, they’re staying longer and exploring farther afield.

At Walpa Gorge, where the sheer cliffs of Kata Tjuta’s domes tower over us, evidence remains of a massive downpour that occurred about a month before our visit, creating thundering waterfalls down the rock faces. In waterholes and puddles along the path we see hundreds of tadpoles. They will mature quickly into burrowing frogs, then hibernate in the hot dry soil for up to a year until the next rain. We keep an eye out for the tracks of birds, lizards and snakes and the burrows of hopping mice.

On our way to Uluru, the vertical black brushstrokes of desert oaks are striped against the bright orange desert sand, and anthills congregate like standing stones. The resort minibus stops en route while a juvenile sand goanna, commonly known as a tinker, swaggers across the road.

The scar of many thousands of footsteps still can be seen stretching up from the so-called Chicken Rocks where the climb began. So much rubbish (and human waste) was deposited on the rock in the preceding decades that it will be many years before the waterholes that form at the base after rain are clean enough to attract wildlife back to the area.

Mutitjulu waterhole is, nonethethless, a place that leaves you breathless. Reached through a leafy trail lined with long grasses and river red gums, it’s an extraordinary oasis amid the arid surrounds. Stand here, alone, and listen to the silence. Forget the chaos of 2020 — it’s a mere blip in this timeless land — and imagine what life was like here tens of thousands of years ago. A short distance away, resort staff are serving delicate canapes with chilled bubbles and beers. As the sun sets, the oxidised arkose sandstone of Uluru turns the most vivid shade of tangerine imaginable. It feels a privilege to be at such proximity to the rock at this hushed hour.

At Longitude’s signature Table 131 dining experience, where the likes of scallops in pepper-berry butter and seared salmon with caramelised fennel are conjured from an impeccable camp kitchen, we sit on a circular timber deck under a night sky brimming with stars. Our host, Brogan, points out Pleiades, the Seven Sisters who, in the Indigenous story, leap into the sky to escape a lustful pursuer, perhaps the original stalker. The morality tale of the three brothers of Orion, who are punished for eating their totem kingfish, is a reminder to obey the rules.

Out here, we’re told, you can spot a shooting star every 12 minutes. If that’s a rule, it’s broken back on the deck of our tent, where it seems celestial diamonds zoom across the glittering night-time canvas every couple of minutes. We’ve returned from dinner to find the gas fire burning outside and a swag set up on the double daybed, a tray of nightcaps and sweet treats to hand. We snuggle down in the cool evening air and look up, gazing at the heavens until the stars blur.

Back at the Dune House the following day, Janet’s chair is empty; her completed painting lies on the table. As an observer, it’s immensely satisfying to see the finished product. Having witnessed the work in progress and spoken with its maker, it’s as though we somehow feel a part of the creative process. Ngapartji-ngapartji, indeed.

In the know

Until March 31, Longitude 131 is offering 20 per cent discounts on stays, minimum two nights. Luxury tent, $1360 a person a night; Dune Pavilion, $2720 a person a night; including all dining, beverages, airport transfers and signature experiences such as visits to the Field of Light. Packages available.

luxurylodgesofaustralia.com.au

Jetstar operates direct return flights to Ayers Rock Airport 12 times a week: six from Sydney and three each from Melbourne and Brisbane.

Penny Hunter was a guest of Longitude 131.