Tour of France from Lyon to Paris visits birthplace of cinema

This tour takes cinephiles back to where it all started – the world’s first movie screening, when people fainted, screamed and bolted for the exit.

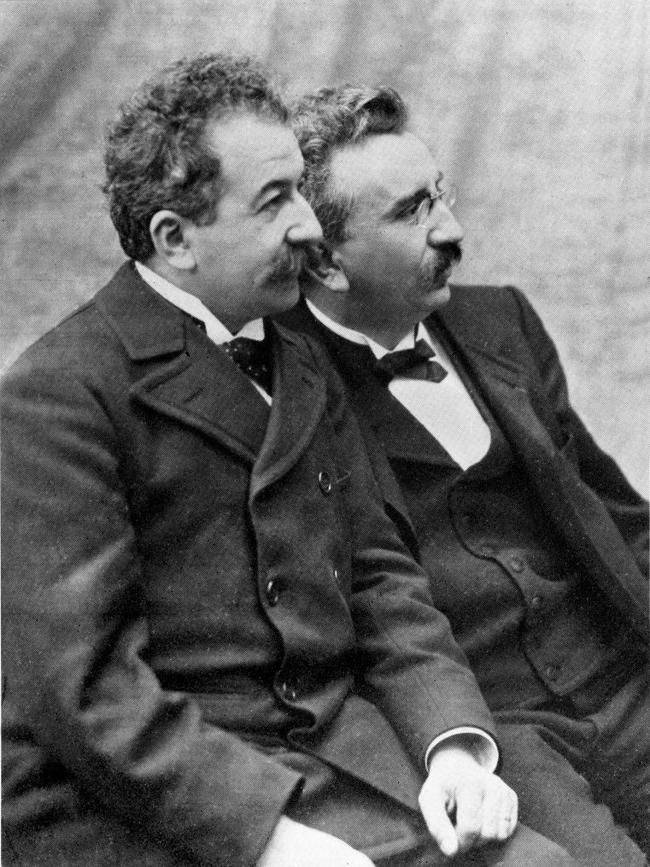

On December 28, 1895, on the basement wall of Le Grand Cafe Capucines in Paris, a steam locomotive rounded a set of railway tracks and loomed, ever larger, towards a group of invited guests. This was The Arrival of a Train, a 45-second recording of a train pulling into a station in France, and the first movie screening. Allegedly, there was mayhem. People fainted, screamed, bolted for the exit. Up the back, hunched over their cinematographe, a three-in-one device that could record, develop and project motion pictures, brothers Louis and Auguste Lumiere kept cranking its handle.

“The public had no concept that this technology had been invented,” says the wiry, likeable CJ Johnson, a Sydney-based film critic and lecturer, standing next to that self-same cinematographe – a portable wooden box with brass fittings – in the Musee Lumiere in Lyon, east-central France.

“They had only known paintings and black-and-white photographs so moving pictures must have seemed freaky.” He flashes a smile. “But also utterly magical.”

It’s the start of a nine-day cinema-focused adventure organised by Renaissance Tours with the Art Gallery of NSW, and we’re at movie-making ground zero. Around us, across all four floors of the art nouveau villa that was previously home to Antoine Lumiere, a photography business magnate who moved to Lyon with his sons in 1870, are technical creations related to images still and moving. They include the earliest colour photographs, and Thomas Edison’s projector-less kinetoscope, squinted at through a peephole. Looping on a screen is Workers Leaving the Lumiere Factory, the first film, made by Louis Lumiere at the gate of the villa’s adjacent le Hangar, and showing mainly female employees in floral hats and leg-of-mutton sleeves exiting the premises. The factory is now the Institut Lumiere, a 269-seat cinema screening rare and classic films, many of them restored and most of them French.

The highest-grossing films in France are French-language films, Johnson tell us in talks that he peppers with excerpts from French movies: 1962’s Cleo from 5 to 7 by feminist director Agnes Varda; 1974’s Going Places, a road movie starring Isabelle Huppert and Gerard Depardieu; Bertrand Tavernier’s The Watchmaker, also 1974, a crime drama cum psychology study set in Lyon’s historic old town.

Johnson is a Francophile and cinephile who originally visited Lyon as a film student and says that seeing the cinematographe in the birthplace of cinema was “like a Christian seeing the Turin Shroud”. His knowledge and passion are hallmarks of the expert-led cultural trips curated by Renaissance, whose arts tours often are scheduled to coincide with key events such as Art Basel in Hong Kong or the Ring cycle at the Vienna State Opera. Our dates have dovetailed with the 16th annual Festival Lumiere, a week-long city-wide celebration of the history of cinema, in the place where cinema began.

Nowhere is the French love for cinema more evident than at the festival’s opening ceremony inside the sold-out Halle Tony Garnier stadium, where 5000 quotidian Lyonnaise deliver a sing-a-long, phone-lights-in-the air tribute to the beloved (recently deceased) French actor Michel Blanc, crane forward in their seats for a screening of the 1946 Lyon-set melodrama Un Revenant, and cheer on starry guests including Monica Bellucci, Tim Burton, Vanessa Paradis and Benicio del Toro – lined up good naturedly onstage – in loudly, joyously, declaring the festival OUVERT.

Across five days we’ll watch several films with English subtitles at cinemas within “flaneuring” distance of our hotel, our appreciation of the themes, of the filmic medium, deepened by Johnson’s talks. “French cinema allows for conversation,” he’ll say. “The French favour character over plot.”

We’re staying in the upmarket Presqu’ile district between the city’s two rivers, the fast-flowing Rhone and the slow-flowing Saone, and its two hills, Fourviere and Croix-Rousse. My hotel room balcony affords a dramatic view of the gleaming white exterior of Notre Dame de Fourviere Basilica, a hilltop landmark built in the 1880s as a way of thanking the Virgin Mary – rendered in blinging gold atop the next-door chapel – for sparing the city from invasion during the Franco-Prussian war.

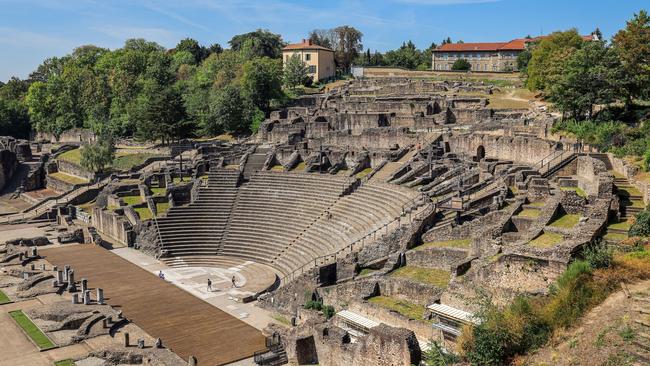

We’ll get to marvel at the basilica’s soaring mosaic-and-marble interior after we’ve perused some other UNESCO World Heritage-listed areas along the way. Lyon is an immensely walkable city, with a history that begins on Fourviere Hill with the ruins of Lugdunum, which was founded in 43BC and became the capital of the Gauls during the Roman Empire. Objects related to Roman-era Lyon are housed next to the site, in a museum-bunker designed in the 1970s by French architect Bernard Zehrfuss and blending so deftly into the landscape it is almost invisible to the eye. Inside, two huge light-channelling windows make the ruins seem part of the exhibition – or like a scene in a movie.

We stroll into Vieux-Lyon, Lyon’ s old town, which has the most Renaissance-era architecture of any French metropolis. Here are pastel-coloured stone mansions with tiled roofs, staircase towers and covered traboule passages created as short cuts and used as escape routes for the French resistance during World War II. Facing demolition in the 1950s, Vieux-Lyon is now a protected treasure, the grime that coated its facades – evident in The Watchmaker’s chase scenes – long scrubbed away. Along its cobbled streets are bookshops, boulangeries and a museum celebrating Guignol – a puppet symbolising the canuts, the silk industry workers whose clicking looms soundtracked Lyon for centuries. Here, too, is the Museum of Cinema and Miniatures, which boasts a collection of cinema exhibits from feature-length films such as Star Wars (Princess Leia’s bra), Mary Poppins (Mary Poppins’s umbrella) and Vertigo (the camera used by Alfred Hitchcock), and more than 1000 tiny reproductions of everything from a Japanese temple to the lamp-lit Art Nouveau interior of Maxim’s restaurant in Paris.

Lyon is also a gourmet’s paradise, boasting the largest number of Michelin-starred restaurants and famous chefs outside of Paris. We eat delicious multi-course meals at restaurants with gingham napkins and floral antique plates (Le Bistrot d’Abel) and desserts so amazing we applaud them (the ile flottante at Marguerite), then head across to Les Halles de Lyon Paul Bocuse, a covered market overseen by a giant wall mural of the chef known as the Pope of Gastronomy. We watch frog’s legs being fried and pike dumplings being made, and I say “non, merci” to the gratton (bits of fried pork fat) and gateau de foie de volaille (chicken liver cake) and “oui!” to pink sugar praline brioche and coussin de Lyon, pillow-shaped pieces of green marzipan filled with curacao-flavoured chocolate ganache.

We visit the Beaujolais wine province, a sub-region of Burgundy 25km north, dropping into the Hospices de Beaune, a riot of Flemish-Burgundian architecture (and a setting for the 1966 French British comedy hit The Great Stroll), along the way. Over lunch at Chateau des Ravatys, a stately pile surrounded by 34ha of vineyards, we sip crisp whites and flavoursome reds produced from organic chardonnay and gamay grapes, and Johnson namechecks the lauded 2013 documentary A Year in Burgundy, a paean to French wine-growing traditions. On this trip, art and life are always intertwined.

Our two days in Paris, a city with more cinemas per capita than any in the world, keep the metaphorical cameras rolling. Inside the striking, Frank Gehry-designed La Cinematheque francaise (“Like a dancer lifting her tutu,” the architect said of the building’s sculptural aesthetic), we explore a permanent exhibition of work by French illusionist and motion picture pioneer George Melies, goggling at his 1902 sci-fi short A Trip to the Moon, its assemblage of wizards, sailor girls and frock-coated boffins newly hand-coloured, and given a postmodern soundtrack by French electro-popsters Air.

In Le Brady, an independent cinema on Boulevard de Strasbourg, we get a private screening of The 400 Blows, the 1959 coming-of-age classic by French auteur Francois Truffaut, co-founder of the influential French New Wave art film movement. We take a guided walk between the Church of the Holy Trinity and Place de Clichy to see the film’s settings in real time.

Our final stop is Montmartre Cemetery, a secluded resting place where winding paths lead past the burial plots of key cultural figures such as composer Hector Berlioz, painter Edgar Degas and actor Jeanne Moreau. But it is Truffaut (1932-84) to whom we’ve come to pay our respects.

“So, we have gone from the birth of cinema to the death of one of France’s most influential filmmakers,” Johnson says as we gather around Truffaut’s flower-strewn grave. “It is through Truffaut and his colleagues that France continues to embrace cinema, and I hope you will too.”

Which in true cineaste’s parlance means, that’s a wrap.

In the know

Renaissance Tours will conduct a 12-day art trip, Authors and Artists of the South of France, led by author and broadcaster Lucienne Joy, departing May 10 from Nice and concluding in Aix-en- Provence. From $11,950 a person, twin-share. For details of the next cinema-themed trip, keep an eye on the Renaissance Tours website.

The Musee Melies is at La Cinematheque francaise.

Jane Cornwell was a guest of Renaissance Tours.

If you love to travel, sign up to our free weekly Travel + Luxury newsletter here.

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout