This river run is one of the great Australian road trips

Follow one of the nation’s most important waterways on a journey filled with bush folklore, legendary sheep barons and Indigenous heritage.

It used to be a 250km trek from the grand homestead at Dunlop Station to the farm’s back fence. In its heyday, this vast property in outback NSW covered almost 400,000ha of scrubby grey loam and red-dirt country. It was owned by Samuel McCaughey, an ambitious Irishman on a mission to amass land and wealth during the “sheep’s back” era of pastoral glory in the late 19th century. McCaughey was an innovative fellow. He quickly realised the importance of water in a region where rainfall and the levels of the Darling River are reliably unreliable, and set about building dams, drilling bores and establishing large storage tanks. He experimented with sheep breeding and irrigation, became a member of NSW’s Legislative Council and was eventually knighted. And when the federal Land Tax Act was passed in 1910, he gave much of his fortune away.

McCaughey’s story is just one thread in the rich fabric of the 950km Darling River Run, a road-tripper’s delight that stretches from Brewarrina in NSW’s central north, west to Bourke and Wilcannia, and south to Wentworth, where the Darling meets the Murray.

It’s a route paved with bush folklore, Indigenous heritage and warm country hospitality, and it’s enormously popular with travellers with time on their hands and the means to do it in style. Expertly kitted-out 4WDs tow five-star caravans and camper trailers on bitumen and dirt, tracing the waterway and taking detours to see the opal fields of White Cliffs, the rock art of Mutawintji National Park and the ephemeral lakes of Menindee.

These days, Dunlop Station is, in some ways, a shadow of its former self. Measuring a mere 880ha, it sustains only about 700 sheep and goats, but owner Kim Chandler is nurturing the land and keeping this fascinating slice of history alive. Six days a week, she generously invites tourists into her home. On the veranda where McCaughey once hosted dignitaries and businessmen, she tells the story of the canny Irishman and the sprawling pastoral empire – 1.3 million hectares at its peak – he built with his brother. She also details how she came to buy the property, virtually sight unseen, from a couple who had holed up in the place, accumulating piles of junk and threatening with firearms anyone who came poking around. It was quite a task to clear out their detritus, re-establish electricity and plumbing, and conduct repairs, but the sandstone homestead, with its soaring plaster ceilings, original Axminster carpets and antique furniture, transports visitors into a time warp.

Chandler’s entertaining tour takes in the 45-stand shearing shed where, after some intense negotiations with recalcitrant shearers, the first fully mechanised shearing session took place, in 1888, powered by the Wolseley machines that would revolutionise the wool industry. Visitors also see the imposing Dunlop Store where McCaughey’s employees could buy everything from booze to bridles and boots, goods shipped up and down the Darling on barges. Wandering through the cavernous space, you’ll find saddle bags, blacksmith tools and boxes of nails still on the shelves as though awaiting a customer.

“A lot of people go away from our tours with a renewed interested and a ‘wow’ about the history of the area,” says Kim. “At the same time, the income we’re earning is helping us to put the property back together.”

My abridged version of the Darling River Run began a few days earlier – after a long day’s drive from Sydney – in Brewarrina, where the Barwon and Culgoa rivers merge to form the Darling. Barred windows, impenetrable fences and boarded-up businesses signal the trouble seen in a town where disadvantage can be traced, at least in part, to the massacre of 400 Aboriginal people in the late 1850s. But it wasn’t always thus. “Bre”, as it’s known, is home to one of the oldest human-made structures in the world. Fish traps, created from carefully positioned stones in the Barwon River, enabled Indigenous people to corral and catch fish for thousands of years. Eight tribes would gather on the riverbanks to partake in the seasonal bounty. At the Brewarrina Cultural Centre, guide Bradley Hardy outlines the traps’ ongoing importance to the community.

“What’s so powerful about the fish traps after all these years? It’s a powerful meeting place, gathering place, sharing place – that’s our home,” he says.

About 100km further west is a town synonymous with the bush and beyond. The phrase “Back o’ Bourke” was coined by Scottish poet Will Ogilvie, who arrived in the riverside settlement by Cobb & Co coach in 1889. He spent 12 years droving and working on stations from the Channel Country in Queensland to the Murray’s end in South Australia, and described the outback as a place “where the wildest floods have birth … the bitterest land of sweet and sorrow”. Henry Lawson, too, had a stint in the town, sent by his editor at the Bulletin in the hope he might lay off the bottle and find some good yarns. He succeeded on one of those fronts, finding plenty of grist for his creative mill. As Lawson famously quipped: “If you know Bourke, you know Australia.”

But he was no romantic when it came to the harsh realities of life out here. His poem, The Song of the Darling River, laments the stream’s inability to be a constant source of life because of drought and mismanagement. Given the fierce debate that continues to surround the Murray-Darling Basin, the sentiment remains relevant. In the 13 years Kim has lived at Dunlop, she’s seen the river full only five times.

Lawson wrote:

The skies are brass and the plains are bare,

Death and ruin are everywhere –

And all that is left of the last year’s flood

Is a sickly stream on the grey-black mud

The salt-springs bubble and the quagmires quiver

And – this is the dirge of the Darling River.

You could spend hours at the excellent Back o’ Bourke Information and Exhibition Centre, where names such as cattle king Sidney Kidman, Harry “Breaker” Morant (a legendary horseman in these parts), Afghani camel merchant Abdul Wade and explorer Charles Sturt, who searched fruitlessly for an inland sea, are all part of the town’s history. As is the river, on which fortunes were made during the booming age of the paddleboat. The Darling is the colour of milky tea, flowing low and slow in its deep channel during my visit. It must be quite a sight when the waters arrive from Queensland, turning trickle into torrent and breaking the banks.

Heading west from Bourke takes you deep into the outback. Interminable stretches of red dirt vanish into the horizon. The unsealed highway looks so smooth and wide a jumbo jet could surely land with little more than a bump. Every now and then a B-triple road train roars past, the lack of tarmac seemingly no obstacle to reaching its destination. Red kangaroos bound off into the mulga and gangs of emus flounce waywardly in front of our car, their feathery skirts bouncing as they run. There are goats everywhere. Once labelled feral, they’re now called “rangeland” and they’ve become a crucial part of the rural economy. Anyone can claim ownership of ruminants that wander on to their property, and they’re typically rounded up, trucked off to slaughter, halal style, then shipped to the Muslim market. As Liz Murray of Trilby Station, which adjoins Dunlop, writes in the info booklet handed to guests: “Without a doubt, no grazier would still be viable here … without the income provided by feral goats over the years.”

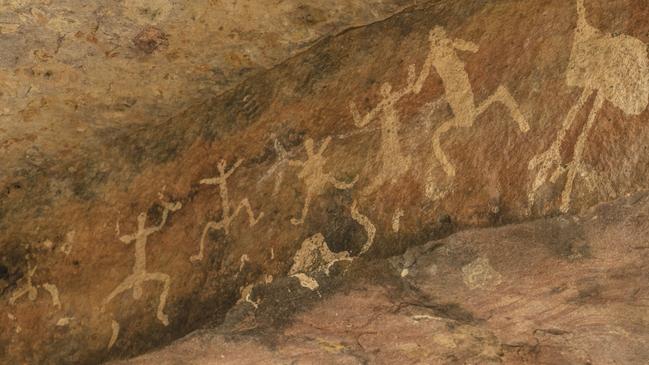

The campground in Gundabooka National Park is spartan but dotted with caravans. Travellers tend to fires as darkness descends and the stars emerge, twinkling in the cold night air. There’s a gentle communal vibe that requires nothing more than a wave and a brief “hello”. The next morning, my husband and I take an easy stroll to the oddly named Little Mountain lookout where we survey the imposing hulk of Mount Gundabooka. A short drive away is the Yapa Mulgowan Art Site, a hushed and special place that shows the richness of the area’s Indigenous links. Located in a tranquil gully sliced in half by a creek, its craggy caves and overhangs are adorned with hand stencils and painted figures. As I descend into the gorge, holding on to boulders for balance, I can’t help but think of the hands of the Ngemba and Paakandji people that may have gripped the same rocks.

Later that day, we hoof it through grassy woodlands in the Valley of the Eagles to summit Mount Gundabooka itself. It’s a solid climb as we tread gingerly across the scree, but the prize is a magnificent vista across plains stretching into the distance. On our return we gaze back at the rocky escarpment, glowing golden in the late afternoon light like the towering ramparts of a citadel.

Pastoral history is back on the agenda in Toorale National Park, once part of millionaire McCaughey’s colossal real estate portfolio. He built another substantial homestead here, beside the Warrego River, as a wedding present for his niece. Clad in corrugated iron, with wide verandas and five chimneys, it was reportedly an elegant abode decked out with handpainted wallpaper and the very best furniture imported from Europe. Visitors are welcome to explore the grounds but the house is fenced off for safety reasons. Lawson, who worked here as a roustabout, might have wandered through the old forge where a giant set of bellows now stands covered in dust and cobwebs. Did he lean against the silvery timber of the post-and-rail yard, worn smooth by time, weather and unknown hands? Did he meet either of the two men whose unfortunate demises are marked by a pair of gravestones: 23-year-old Paddy Taylor, killed by a fall from his horse, and Robert Kirkpatrick, who was mysteriously “found dead”?

Away from the homestead the rust-red landscape feels infinite, stretching flat and featureless. Yet take a turn off the national park’s main thoroughfare and you’ll find the Warrego flood plains, a place of almost unfathomable watery abundance. Birdwatchers are drawn here to see brolgas, bustards, cormorants and pelicans. Black swans and ducks paddle among the reeds while parrots chatter excitedly in coolabah trees. In such an arid region, it feels like paradise.

Floods are a fact of life at Trilby Station, once part of the Dunlop operation and now a 130,000ha working property about half an hour’s drive from the hamlet of Louth, where the road crosses the Darling. Fifth-generation farmers Liz and Gary Murray have created an excellent set-up for travellers, with camp sites arranged along the river, around a billabong or at a central area with power access, a communal fire pit, camp kitchen, and bathroom and laundry facilities.

When heavy rains flow south from Queensland and meet the Darling, the Murrays have weeks to prepare for what could be four months of isolated island living, surrounded by flood waters. They buy up supplies, move livestock and machinery to higher ground and ensure the dinghies, chopper and Cessna are in reach. The property is high and dry during my visit, and we snaffle a site on the billabong, watching galahs bicker in the river gums and pelicans glide silently on patrol along the water at dusk and dawn.

For city dwellers like me, Trilby provides captivating insights into life on the land: a life of fickle weather and fluctuating stock prices; of self-reliance and resilience; of the challenges and joy of raising children remotely.

“We just love the lifestyle … and it’s good to be able to show the people who come out here why we love it so much. It gets into your blood and the dirt gets under your fingernails – and in your ears and up your nose,” Liz says with a laugh.

Weeks later, I’m still finding red dirt in the crevices of my car. It’s a reminder of one of Australia’s storied road trips, and a promise of the parts of the Darling River I’m yet to see.

In the know

The Darling River Run website is packed with useful information on the route, accommodation and points of interest.

Dunlop Station is 135km from Bourke on Toorale Road. Tours operate seasonally, Tuesday to Sunday, 11am; $20 for adults, with morning tea. Unpowered camping sites are available along the river; $20 a night for two.

Brewarrina Cultural Museum is open Monday-Saturday and offers four daily

tours during the week, two on Saturday; $25 an adult.

The Back o’ Bourke Information and Exhibition Centre is open seven days a week. To visit the exhibition costs $23 an adult.

Trilby Station has unpowered campsites from $25 per couple a night; powered sites from $40; three cottages range from $150-$180 a night.

Outback Beds is a network of more than 20 accommodation options in outback NSW and southwest Queensland.

Penny Hunter travelled at her own expense.

If you love to travel, sign up to our free weekly Travel + Luxury newsletter here.

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout