This luxury cruise will leave you wild about the Kimberley

Locals are wild about WA’s wilderness frontier - and a luxury cruise ship is the ideal way to drink it all in.

There’s a moment on any good expedition cruise when the unimaginable happens. You know what you’re meant to expect on your trip, of course – you’ve read the brochures, you’ve seen the photos – but this beat of exhilaration is one you can never anticipate or plan for. You feel it rather than see it or hear it: it’s as though your synapses are suddenly buzzing together with a lot more energy than usual. It’s a dense, lung-filling joy, and a sense of profound gratitude that no one has ever experienced this exact moment before, nor will again.

That episode unfolded on day nine of my 11-day cruise from Broome to Darwin through Australia’s Kimberley region on Silversea’s Silver Cloud, when the ship anchored in Koolama Bay at the mouth of the King George River. At 6.30am, ours was the first Zodiac out, so the water was glassy and undisturbed by anyone else’s growling outboards or choppy wake, and the first rays of the sun were beginning to burnish the huge sandstone cliffs from a shadowy dark orange to a bright blazing copper.

Our boat had lucked out with the exact expedition guide you want when you’re exploring the most geologically interesting leg of the journey: Graeme Hillary from South Africa, or “the rock guy”, as he was known among the guests. A geologist with a fondness for wraparound sunglasses and neon rashies, Hillary swoons before interesting erosion patterns or smudges of cyanobacteria the way an epicurean might melt at the taste of lightly seared foie gras. He was infectiously enthusiastic; a morning spent examining rocks will convert you to being a “rock guy” pretty soon, too.

-

So the scene was perfectly set for “the moment”, which came when the Zodiac swooped around a wide bend in the river and the ancient grace of the Kimberley was framed in technicolour. The engine was cut and we sat and watched and breathed and felt – totally speechless, utterly moved. Hillary’s earlier commentary had primed us to understand the staggering age of these jagged cliffs, Jenga towers of blocky, geometric shapes, which have been stretching out of the teal green water and into the sky for hundreds of millions of years. The land and sea were bisected by a caramel-coloured lattice of honeycomb erosion.

“It’s called tafoni,” he told us in tender tones. On the shore, a quick neon-blue flash grabbed our attention as a sacred kingfisher darted between the mangroves. We had seen plenty of extraordinary sights on this trip already – the racing rapids of the Horizontal Falls, the astonishing aqua-blue of the clouds as they reflected the colour of Ashmore Reef, and the time at Montgomery Reef when my eye happened to be focused on the exact spot on the water where a slate-grey dugong curved into view as it took a breath of air. But there was something about this particular still, serene scene that was almost shocking in its beauty. Our perceptive guide was the first to break the silence. “Oh, man. This is awesome. It’s like we’re the only people on Earth.”

We were, in fact, some of the only people in the Kimberley at least. The region, once a separate landmass that mashed into the larger Australian continent 1,800 million years ago, is roughly three times the size of England, but has a population of only 35,000, mostly in towns like Broome and Kununurra. Silversea has been sailing this remote coastline for a decade, but even with a recent uptick in interest from other cruise lines, the vast emptiness out here is indisputable. Every so often you might see another ship in the distance, but when you take your place on that first dawn Zodiac, it really is just you and nature turned up to full volume.

-

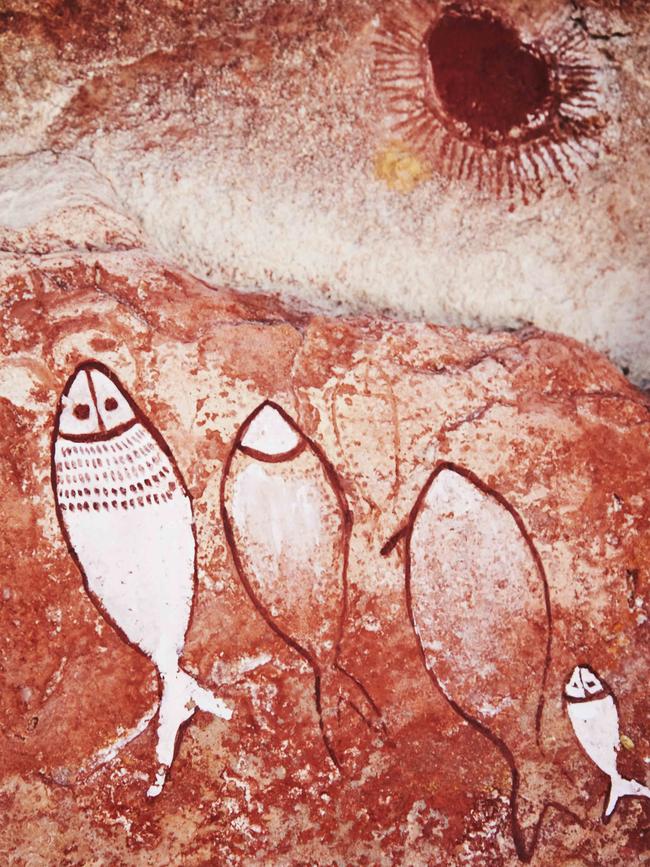

The sense of emptiness was somewhat deceptive, however, since people have lived in this forbidding terrain for tens of thousands of years. Beyond the landscape and the wildlife, the major draw for a Kimberley expedition like this one is a chance to explore the artwork of some of the 30 First Nations cultures that occupied these lands for at least 40,000 – and perhaps as much as 65,000 – years. There are two types of rock art around here, both unique to the region. The wide-eyed Wandjina figures surrounded by haloes of lightning depict creation gods, and their likeness is still painted by First Nations artists today. The older, more mysterious lanky figures of Gwion Gwion art are less understood, though equally captivating.

On day three of our expedition our Zodiacs hauled out to one of the thousand tiny islands of the isolated Buccaneer Archipelago. This was Freshwater Cove, known as Widgingarra Butt Butt in the language of the Worrorra people, a description of the spotted quoll said to have shaken its spots off to form the creek that twists its way along the shoreline. Our guides, Gideon Mowaljarlai, Neil Maru and Raelarni Charles from the Arraluli clan, daubed our faces with smudges of ochre as part of a Welcome to Country ceremony, before Maru led us to Cyclone Cave to give us our first glimpse of these ancient markings.

-

As we returned to our inflatable craft, a rumour went round that we had just missed meeting Snappy, the large territorial croc who regularly patrols the water around here. “Oh, no, that wasn’t Snappy,” Maru said with a grin. “That was Nibbles.” There are two of them? I hastily stepped back from the water’s edge. Snappy and Nibbles might sound cute, but I expect, up close, they are very much not. Later, at Jar Island in Vansittart Bay, we observed the mystical Gwion Gwion art. No local First Nations groups claim it definitively as their own. The only steady belief they share is that the Gwion Gwion bird created the paintings with its own blood. “The oldest art in France has been completely closed off to the public – you can only see a replica,” said Will Versluis, a Silversea guide and anthropology lecturer, referring to the Paleolithic art of the Chauvet Cave in southern France. “Yet we can stand right here and see this art up close.” He made a “mind-blowing” gesture to his temple and the group nodded in shared awe.

Silver Cloud, which replaced its sister ship Silver Explorer in the Kimberley this year, is in stellar shape for a vessel built in 1994. “It’s pretty good to have a hotel of this calibre in this remarkable location,” expedition leader Peter Bergman pointed out during one of our daily recap sessions, and he was right. The ship has had two major refurbishments since then, in 2017 and 2023. Unlike Silver Explorer, Silver Cloud has an open-air pool, which saw a lot of traffic on our voyage’s hottest days. My deck four suite was perfectly spacious, with a walk-in wardrobe and a two-seat sofa – the ideal spot to enjoy 4pm Champagne and caviar, brought each day by my liveried butler, Suraj.

The dining variety, while not as broad as on an ocean vessel, was thoughtfully calibrated for days spent adventuring – most of us gravitated towards light salads and cold meats in La Terrazza for lunch, then something more substantial for dinner at either The Restaurant or the flamboyantly French La Dame. The former is the place for grilled filet mignon or New York strip steak, and exquisitely prepared Indian curries. La Dame is all dramatic silver cloches, flowers and foams. The bisque de homard – lobster bisque – and the colourful wreath of fresh fruits and berries in the assiette de fruits dessert topped and tailed one memorable three-course meal.

-

Of the 212 guests, most were Australian, with a smattering of Americans, Brits and Kiwis and a solitary Austrian. You’ll find Australians on almost every cruise ship in the world, but so many is rare, and it was nice. They didn’t gorge themselves on obscene amounts of food. They were generous about dispensing ibuprofen or sunscreen if you’d left yours at home. And, for the most part, were fit, active and early to bed. Unsurprisingly, they do like a drink. “We always have to bring on extra alcohol when we have a lot of Australians on board, especially beer,” hotel director Ivar Drageseth told me. Best of all they seem truly adventurous and curious. Adventure tends to lose a bit of its lustre if you’re not experiencing it with people who are as enthusiastic as you are.

I shared my moment of awestruck grandeur on the King George River with my fellow Zodiac crew. As our guide sputtered the craft back to life we glided past a two-metre crocodile sunning itself on a barely visible rock in the centre of the river, its jaws open in the proverbial “smile” that the nursery rhyme urges you never to return. Later, we squealed with laughter as the Zodiac raced under one of the two towering King George Falls, and we emerged dripping and elated. Then we motored up to a Zodiac manned by the ship’s hospitality team bearing celebratory glasses of Champagne – an expedition ship tradition that takes place in some of the most beautiful and remote parts of the world.

There were many more boats and guests around us now so the landscape had lost a little of its silent, faraway magic and we sat back with our fizz to chat, getting to know each other. Caroline was from Perth, and her daughter lives in the Pilbara, so she had already explored this area a fair bit on land. Why did she choose this voyage? “We want to get out and really get among it,” she said as the cliffs cast long shadows over our boat and a solitary brahminy kite circled overhead. “Australians should have a lot of pride about this region. This is ours.”

The writer travelled as a guest of Silversea. The company has six Kimberley cruises scheduled for next winter.

This story is from the October/November issue of Travel + Luxury Magazine

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout