Think you’ve been everywhere? This scarcely visited kingdom awaits

You’ll be welcomed royally as one of only a few tourists who visit this pristine paradise each year. But be warned, this is the only country to have a daily ‘sustainable development’ tax for travellers.

When Bhutanese people go to the temple, they make supplications and offerings not just for the protection and redemption of themselves and their loved ones but for all sentient beings. And that includes you, Dawazan, so move forward, sturdy little horse that you are. The entire country is behind you, so cast off your doubts. We have your back.

Yet I feel Dawazan wants to cast me from her back, for this track up to Tiger’s Nest, a breathtaking monastery above the Paro Valley, is steep, and she pulls up often, disgruntling her handler, Daw. She takes no inspiration from his headgear, a Ferrari cap with its prancing horse, and the fact he wears it backwards is perhaps a sign to Dawazan that she too should turn around. But on each occasion, with admonitions from Daw and firm tugs on the reins, she resumes a plodding ascent towards this eerie eyrie.

Tiger’s Nest, or Paro Taktsang, is a foundation stone to the spirituality of Bhutan, and the most accepted legend is that Guru Rinpoche, an 8th-century Tibetan mystic, flew to this ledge on the back of a tiger. After three months meditating in a cave, Rinpoche descended to begin the conversion of these eastern Himalayan valleys to Buddhism. The monastery’s engineering, a stunning feat given it’s been clinging to the cliff 900m above the valley since 1692, makes it a beacon but also a lung-burster in these altitudes, so I happily accept the horseback option. But only to a halfway cafe, then it’s on foot through the cypress forest for me and guide Karma, who’s part of the package at my luxe lodging, Amankora Paro.

The monastery has a dozen temples, and monks sit cross-legged in several, quietly chanting. A distinctive door, behind which Rinpoche is believed to have meditated, is opened once a year, on a date determined by the astrologers. The oldest relic here is a statue of the Guru, which has survived two fires and potential dissection. Legend has it that while struggling to tote it up the mountain, its bearers discussed easing the load by cutting it up. And then the statue spoke. “There’s no need for that, a strong man will come and carry me.” That strongman is Singye Samdu, lauded as the protecting deity of Taktsang.

In Bhutan, such spirituality is felt at every turn, particularly breezy corners on mountain roads where the wind catches massed stands of prayer flags to blow blessings and teachings across us all. Every home flies five coloured flags representing the elements, their grouping signifying harmony. Most also have a shrine room, and it’s in one, in a village in the Haa Valley awash with red rhododendrons, that I witness a springtime ritual of cleansing known as so-choe. Here monks, some barely in their teens, are chanting, drumming, clashing cymbals and blowing horns, one of which looks decidedly strange. “It’s a kangling, a femur trumpet,” my new guide, Tshewang, explains, and I’ve not misheard. This human thigh bone instrument is common in rituals such as these involving wrathful deities, and the cacophony is driving the misfortunes and obstacles away for the coming year. The family don’t take part, as they’re busy entertaining, because so-choe is open house, with village visitors fed peppery rice porridge, pork, bitter greens and potato with cheese, plus khapse, a crispy biscuit.

The house also welcomes guests in Bhutan’s homestay program, an immersive experience, particularly in less-developed areas such as Haa. I’m staying at one further up the valley, a humble home, yet I am welcomed royally by Gyem, her sister Bem and niece Namgay. The family otherwise survive on growing potatoes, barley, wheat and turnips, although their crop has been blighted first by a mite and then wild boars, and they’re just scraping by. Tshewang explains the family, like many Bhutanese, believe their misfortune is partly down to superstition, which, he says, may be holding them back from a scientific solution.

Namgay, who’s 10, speaks lovely English and is very attentive, getting me a cushion for the chair, as I can dine the Bhutanese way, cross-legged on the kitchen floor, for only so long; then she provides a side table for my yak butter tea. One morning she appears in a beautiful ensemble of a multi-coloured, ankle-length dress, called a kira, plus a toego, a jacket of rich purple with deep blue cuffs. I think she’s showing me her Sunday best but, no, this is her school uniform. Many Bhutanese wear traditional dress in daily life, and Tshewang gets about in the male equivalent of a knee-length tunic of finely checked woven material called a goh, with knee-high socks (omso).

Weaving is Bhutan’s national art, and the best museum in the capital, Thimphu, is the Royal Textile Academy. The foyer features an enormous silk tapestry of another giant of Bhutanese spirituality, Zhabdrung, a 17th-century master who united these remote valleys to create the nation. Upstairs is an array of magnificent kira and goh, mainly in silk, although wool and cotton are common for everyday wear. Rudimentary items, such as bags, can be woven with nettle, a more rustic yarn. Your take-home souvenir could be a woven scarf, shawl or bag from the street market next to the Textile Academy. Or visit Thimphu’s Gagyel Lhundrup Weaving Centre to watch women working the looms with incredible dexterity and patience. A pure silk kira can have up to 30 colours and take six months to finish, which is why, upstairs in the shop, a proper ceremonial get-up can be $US7000-$10,000.

One afternoon we pass the hubbub of the Changlimithang archery ground, and Tshewang is streaming the match on his phone. Amid the crowd’s whistling and jeering, an archer lines up his shot, while three women form a kind of cheer squad. The exchanges can get quite personal, Tshewang explains, and at times physical.

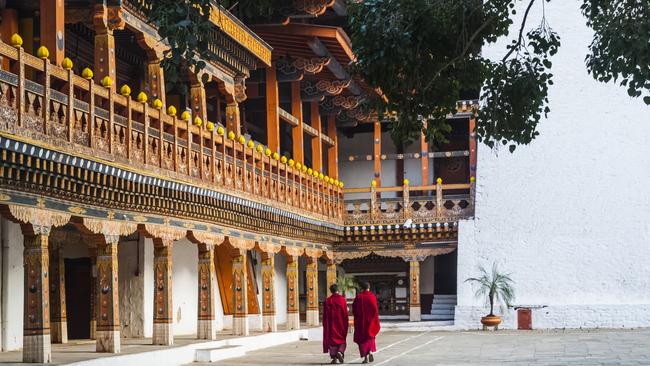

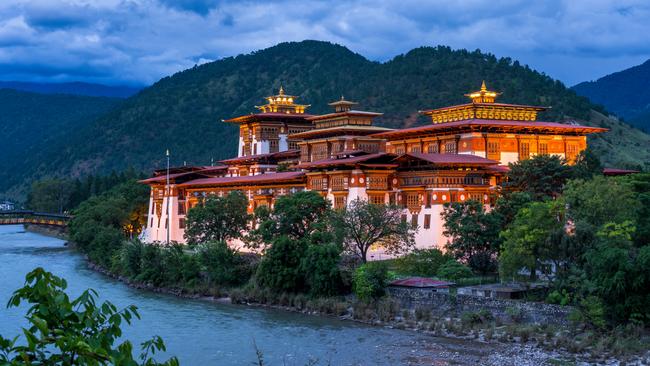

Bhutan’s most storied valley is Punakha, which, although ceding its capital status to Thimphu in 1961, maintains a dominant presence through its main dzong, or fortress, still the seat of the Bhutanese clergy.

Strategically located at the confluence of the Pho Chhu (male) and Mo Chhu (female) Rivers, it stands sturdy and imposing, with a softening line of flowering jacarandas along one side. Its temple is the most impressive I see in Bhutan, high-ceilinged and more open than most but still drenched in iconography.

At its centre is a large Buddha, wall paintings depicting his 12 principal deeds, “basically his life story”, says Tshewang. It’s flanked by the two towering figures of Bhutanese spirituality, Zhabdrung and Guru Rinpoche, but to the side is another significant character, especially in this valley, the Divine Madman. I’ve already come across this chap, at the Royal Wildlife Preserve in Thimphu, where the hallmark exhibit is Bhutan’s national animal, the takin. Resembling a musk ox, Tshewang reckons it’s a bit ridiculous, with the face of a goat and the body of a cow, but that’s its origin story. In the 15th century, Lama Drukpa Kunley was asked for a miracle to prove his powers. So he devoured an entire cow and a goat, assembling the bones to create this creature, which he then brought to life. From then on, Drukpa was known as the Divine Madman, and his most notable trait is potency.

He arrived in Punakha, the legend goes, looking for an arrow he’d fired from Tibet. When he found the roof it landed on, he seduced the woman of the house who bore him a child. Thereafter, the Divine Madman would defeat demons with his “magic thunderbolt of wisdom”, and now householders put phalluses over their doorways to ward off evil spirits. The imagery is everywhere, especially as souvenirs in the village of Lobesa, and displayed in all colours, patterns, textures and sizes. But there’s a sincere side to it, at Chimi Lhakhang, a nearby monastery.

Women come to its temple to pray for their fertility, with some strapping a large wooden phallus to their backs for the traditional circumambulations of the stupa. Inside the temple, a photo album of beaming parents with babies and toddlers is testimony to these people’s faith.My last day is a significant one, Tshewang advises, a day of the protective deities. Bhutan’s calendar is not set in stone but determined only a few months in advance by astrologers, who may deem it propitious to drop certain dates and/or repeat others.

So on a hill outside Thimphu, we visit Simotkha Dzong, which is preparing for the arrival of Punakha monks moving to this higher valley for summer. Students from the Institute of the Science of the Mind are weeding and sweeping with rudimentary brooms, joyously happy in their work, while monks chant and tap narrow green goat-hide drums.

“This kind of ritual is low-key, secret,” says Tshewang. “So it’s kept soft.” That’s because the deities here are peaceful; only negative forces are met with loud bangs to drive them away. The temple has an unusual icon, a black statue that I recognise as Zhabdrung, seemingly the only mystic in Bhutan with a beard. So what great legend is behind the black Zhabdrung, I enquire. “Nothing,” Tshewang says, “It’s just discoloured because of its alloy composition.”

In the know

With its particular customs and protocols, not to mention daunting mountain roads, Bhutan is most easily enjoyed with a guide and a driver, and local tour companies are able to arrange everything. Contact the Tourism Council of Bhutan/Bhutan Department of Tourism or Bhutan Ministry of Foreign Affairs for online visa applications and updates on the government’s Sustainable Development Fee for visitors.

More to the story

Bhutan’s significant collection of high-end lodges are slow-release experiences, slightly outside the main centres and discreetly nestled in forest or on mountainsides. At Amankora Paro, you arrive at an anonymous roadside stop and are escorted through the forest along a path of pine needles to be greeted with the traditional khatat scarf. Only then is the resort revealed, the largest of five Aman properties in central and western Bhutan but still with only 24 suites, across a collection of rammed earth buildings secreted among the trees.

The suites, all identical, are large, reasonably private to the outside, and with sumptuous ensuites dominated by a central bath. They stand separate to the main lodge, which houses a long, glass-walled living room that’s the place for cocktails and nightcaps, or simply drinking in the Himalayan views. Meals, with a diverse menu of Bhutanese, Indian and international dishes, are taken downstairs in the dining room, which flows onto a terrace.

The stand-alone spa includes a glass-walled yoga studio and hot-stone baths inspired by Bhutan’s time-honoured healing rituals. Amankora Paro tariffs include all meals, house wines, spirits and beers, laundry, airport transfer and picnics enroute between the five lodges. Aman can organise a unified trip, dealing with visas and Bhutan’s $US100-a-day “happiness tax”, and will provide guides and drivers. Suites from $US1900 ($2857) a night, twin-share, excluding taxes and fees.

Jeremy Bourke was a guest of Bhutan’s Department of Tourism.

If you love to travel, sign up to our free weekly Travel + Luxury newsletter here.

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout