Things to do on Kyushu, Japan

The past hangs suspended in the present on Japan’s third largest island, where luxury resorts resemble farmhouses and craftspeople offer ample diversions.

As a child, Ayumi Shiiba used to capture hotaru (fireflies) in a straw basket and watch them dance. Now, in her guest-facing role at the newly opened KAI Yufuin hotel in the northeast corner of Japan’s Kyushu Island, she urges me to turn off all the lights at night except a spiral-shaped pendant lamp designed by craftsperson Chika Iwakiri. Suspended above my futon, the lamp is woven from sweet-smelling shichitoi grass grown locally and also used in tatami matting. “It’s a very beautiful light that reminds me of the fireflies,” she says. I later read that Japanese firefly basket lanterns once served as light sources for rural villagers.

KAI Yufuin is built in the style of a ryokan where immersion in onsen hot springs and other aspects of local culture are part of the experience. I’m intrigued by the promise of the lamp, but I’ll need to wait a few hours to try it because the sun is yet to set over terraced rice paddies cascading down the nearby hill. Earlier in the day, I flew into Fukuoka, Kyushu’s capital, before boarding the Yufuin No Mori (meaning Yufuin’s forest) express train for the two-hour journey to Yufuin. Built in 1989, Yufuin No Mori was the first of 13 sightseeing trains now operating in Kyushu. Its classic design with elegant wood-panelled interiors offers a sharp contrast to the country’s sleek Shinkansen bullet trains.

From the station and the charming streets of the main town, KAI Yufuin is a short drive up a winding mountain road, situated amid a thicket of bamboo. With 45 guestrooms, including two free-standing suites, it’s the latest of 20 hot springs properties operated by Japanese-owned Hoshino Resorts under its KAI brand. An understated entrance flanked by walls lined with unsplit bamboo leads into the main building, designed by architect Kengo Kuma to resemble a (very fancy) farmhouse. The dark, subdued reception area and lobby is minimally furnished, and the textured floor mimics the traditional earthen tataki style. The lobby flows into the “travel library”, where guests can help themselves to reading matter and tea, then out to a sweeping deck overlooking rice fields.

The deck, in turn, connects the main building to the onsen, a soothing space comprised of indoor and outdoor baths, along with a post-bathing lounge. With a ceiling made of black woodgrain panels and walls and floors lined with black pebbles, the indoor bath has the same moody charcoal cast as the lobby, dramatically framing views of 1583m-high Mount Yufu. The dining room is located on the lower floor of the main building, where softly lit washi paper walls delineate different seating areas.

The multi-course kaiseki dinner features food rich in flavour that emerges from the kitchen with the relentless efficiency of a sushi train. There’s wild boar meat and shiitake mushroom pate wedged into wafers, soup with abalone fish cake, assorted sashimi, tempura prawns and a shabu-shabu hot pot of thinly sliced beef and game meats, served with dipping sauces.

I return to my room certain in the knowledge that I have overeaten. Before collapsing into bed, I turn on the one special lamp and fall asleep to its gentle flickering, dreaming of fireflies.

The next day, I take the train to Saga prefecture, home to rich cultural traditions, including carpet weaving, sake brewing and tea making. From Takeo-Onsen station in Saga, the Nishi Kyushu Shinkansen line – Japan’s newest and, at 66km and 23 minutes, its shortest bullet train route – runs to Nagasaki, a compelling destination in its own right, but I’m catching a jetfoil to the far-flung Goto Islands, a scattering of about 140 isles off Kyushu’s west coast. Japan’s oldest surviving historical record, the 1300-year-old Kojiki, holds that Heaven and Earth were conjured from primordial oceans, before kami (gods) birthed the islands of Japan. It seems easy enough to believe during the two-hour journey to Fukue Island, the largest and southernmost in the Goto archipelago. Through salt-sprayed windows, I gaze at the muscular, mostly uninhabited, rocky formations rearing out of the East China Sea. The landscape seems just as primeval and mysterious today as it must have done when the Kojiki’s author, an eighth-century scholar, sat down to impose order upon an unruly collection of stories at the behest of Empress Genmei.

From Fukue Port Terminal, it’s a 10-minute journey by road to the Retreat Goto Ray. As manicured trees give way to jungle so untamed it threatens to reclaim the bitumen, guide Miyuki Ogawa notes that Fukue Island is blessed with lush pastures, unspoilt beaches, jungle-clad mountains, the rambling ruins of the last castle built in Japan and a grand street of samurai-era residences. Oh, and a volcano, Mount Onidake. “But the last eruption was thousands of years ago, so don’t worry about it,” she adds.

“Before collapsing into bed, I turn on the one special lamp and fall asleep to its gentle flickering, dreaming of fireflies”

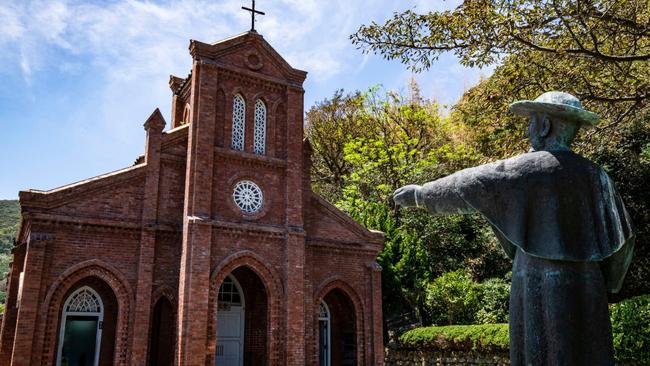

That eruption is what laid down the rugged black “lava coast” rock upon which Retreat Goto Ray is built. Designed by the late Yukio Hashimoto, it forms part of the Okcs hospitality brand. The clean, simple lines of this low-set structure’s exterior reveal little, but step inside, and the 6m-high floor-to-ceiling glass in the lobby reveals breathtaking views of sea and sky. Also eye-catching are the stained-glass windows that pay homage to this region’s Christian heritage, after communities of the faithful arrived seeking refuge from persecution during Japan’s two-centuries-long ban on Christianity (see More to the Story).

Drained of colour, the windows offer glimpses of the vibrant green foliage beyond. Over three levels, 26 spacious guestrooms each feature an open-air onsen, ocean views and abundant natural light. After settling in, I shrug on the supplied yukata robe and head upstairs to the dining room for another kaiseki meal, this time shaped by the abundant produce of the Goto Islands. A keen spear fisherman when not in the kitchen, chef de cuisine Ko Takahira snagged some of the ingredients in the nine-course meal, including mackerel sushi, amberjack sashimi and simmered long tooth grouper. Yet the melt-in-the-mouth grilled Goto beef is the star. The proximity of the sea means the cattle graze on mineral-rich grass, enhancing the flavour and texture of the meat.

The island offers ample diversions. Producers and craftsmen, including noodle-makers, camellia oil-extractors, blacksmiths and oke (wooden bucket) builders, all have open-door policies. We visit the workshop of Hitoshi Yamada, who scoops crystallised salt from giant urns as he explains how to harvest salt from seawater. It’s a process that dates back to the 17th century and here, as elsewhere in Kyushu, the past hangs suspended in the present, close enough to touch.

Denise Cullen was a guest of the Kyushu Tourism Organisation.

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout