The Melbourne Holocaust Museum is life-changing

The recently renovated building in Elsternwick brings history’s darkest days into the light.

Having read extensively about the Holocaust and watched films such as Schindler’s List and The Pianist, I feel some trepidation when approaching the Melbourne Holocaust Museum.

It’s a feeling that only grows when I encounter a formidable security booth beside the closed front door.

It’s a reminder of the fraught times in which we live, and that the hatred behind the genocide of 80 years ago isn’t limited to the past and the other side of the world.

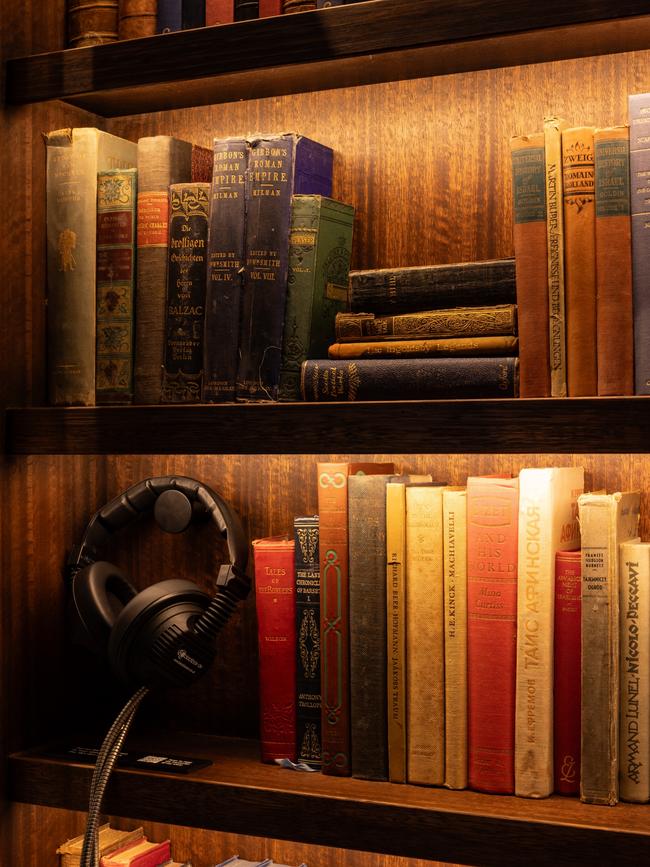

Cleared by security staff, I enter the building and immediately breathe easier amid abundant natural light and softly finished blond wood. Reopened last November after an extensive rebuild, this museum, research and education centre welcomes visitors with remarkable calm. Designed by Kerstin Thompson Architects, the five-storey structure in the inner suburb of Elsternwick won a 2023 national award for public architecture from the Australian Institute of Architects.

The interior garden, the courtyard and terrace offer relief from the museum’s confronting information, stories and artefacts, gathered since this institution was established in 1984 by local Holocaust survivors.

The original two-storey 1920s building’s facade has been subtly retained in the new structure (which follows several expansions over the decades). Honouring the past is important here.

Head of programming and exhibitions Dr Breann Fallon says this place is not just about the past, however.

More than a museum, it’s also a memorial and custodian of memory, she says, yet “it’s as much about the present and the future”. The exhibitions and experiences are designed to help visitors “take those lessons forward” in their own lives. “It’s a social justice project.”

Before entering the main permanent exhibition, Everybody Had a Name, visitors can choose from one of several Melbourne Holocaust survivors as a guide of sorts. Taking the postcard with a youthful photo of Abram Goldberg, I use it at five screens through the exhibition to learn about his experiences in Nazi-occupied Poland, including through video testimony. It’s one of several ways the exhibition breaks this big, dark chunk of history into smaller, personalised parts.

The first of six sections, called The World That Was, explores Jewish life in Europe before the Holocaust began in 1933. It includes black-and-white film of Greek merrymakers, and I learn that 73,000 Jews lived in Greece back then.

It’s the first of numerous surprises for me about the diversity of Jewish identity and experience in the exhibition. Those books and films keep coming – including One Life, in cinemas now, and The Zone of Interest opening February 22 – but they can only begin to tell the millions of different Holocaust stories.

In the next two sections, Rights Removed and Freedoms Lost, I look through a translated facsimile of a 1938 German children’s picture book of appalling anti-Semitic propaganda, and am even more disturbed by a display about eugenics. One side presents the Nazis’ take, which focused on “racial purity”, the other how eugenics was applied in Australia with the attempted “breeding out” of the Indigenous population. A 1937 quote from a Commissioner for Native Affairs is chilling.

In Life Unworthy of Life and Survival Against the Odds, small objects speak volumes. A worn leather handbag, one of few possessions a woman escaped with. A father’s portrait of his young son, painted on a postcard in a prison-like ghetto; they died in the Auschwitz extermination camp.

I’m surprised by photos of Jewish refugees in Shanghai, where 17,000 fled in 1933-39, and in a different way by a substantial model of extermination camp Treblinka. Polish-born Chaim Sztajer, who escaped from Treblinka, handmade it from memory in Melbourne. I wonder at the courage required to willingly return to this place over and over in his mind.

The final section, Return to Life, celebrates Melbourne Holocaust survivors in particular. Food is prominent among their stories. There is the Glick family, for example, who introduced Melburnians to bagels, and Mirka Mora, now mostly remembered as an artist, who established herself here as a restaurateur. My virtual guide, Abram, is a 99-year-old board director at the museum. Even more than it began, Everybody Had a Name ends positively.

It’s not recommended for children under 15, but another permanent exhibition, Hidden: Seven Children Saved, is designed for 10 to 14-year-olds. Technology is used in projections, audio and a virtual reality experience called Walk With Me.

It’s a powerful example of how the museum makes history more meaningful through personal stories with a local connection. Wearing a VR headset, on a swivel seat that enables 360-degree viewing, I follow octogenarian John Chaskiel to his boyhood home in Poland and then on to locations where he recounts more horrific times, including at Auschwitz. We move to happier memories in Melbourne and the film ends at an extended-family gathering with a moment of simple but extraordinary joy.

Carrying a little of John’s joy with me, I exit the museum and search for a Jewish treat. They are easily found here in Elsternwick and neighbouring suburbs such as Balaclava, where most of the 8000 Holocaust survivors who migrated to Melbourne started their lives over again.

At Aviv, a renowned purveyor of handmade bagels and European-style cakes, I buy a chocolate babka. Soft and sweet, it’s a reminder that good things, even life itself, can endure in the face of evil and death.

In the know

Melbourne Holocaust Museum is 9km from the CBD, and just steps from Elsternwick train station. Open Tuesday to Thursday, 2pm-7pm and Sunday 10am-6pm, with extended hours for school holidays and some public holidays. Exhibitions (including temporary ones) and the VR experience are individually ticketed; Everybody Had a Name is $18 for adults.

Melbourne’s Jewish Museum of Australia reopens after renovations on February 29 with a refreshed permanent exhibition, two temporary exhibitions and a new children’s space.

Sydney Jewish Museum’s exhibitions include The Maccabean Hall: Celebrating 100 Years, which reveals the history of the museum’s building from its beginnings as the NSW Jewish War Memorial.

Brisbane’s Queensland Holocaust Museum opened last year.

Adelaide Holocaust Museum opened in 2020.

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout