The Great Barrier Reef’s most seductive new hideaway

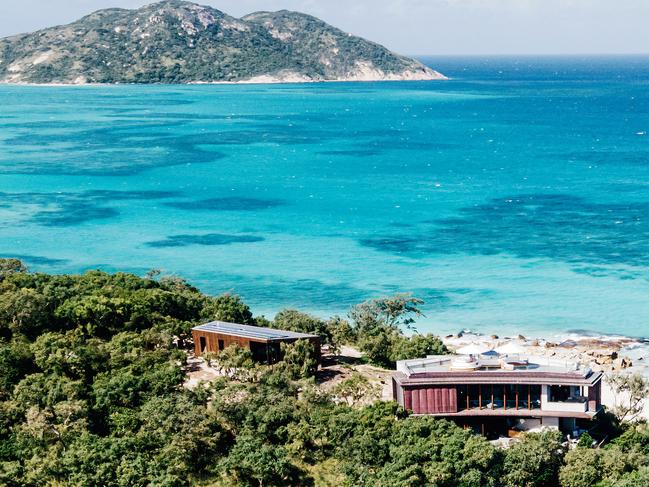

A striking new private retreat on Lizard Island may be the most spectacular and sought-after holiday rental in the country.

This article appeared in issue seven of Travel + Luxury magazine. Pick up a copy in The Australian on Friday, 24 June or explore the full edition online.

Untethered from the mainland, adrift in the Coral Sea, Lizard Island is breathtakingly remote. This unspoilt idyll, an hour’s flight on a puddle jumper from Cairns, is moored in opalescent water, encircled by iridescent reef and lulled by breezes that act like an antidepressant for twitchy travellers. Until recently, the island’s namesake resort – beloved by nature fanatics and wayward romantics alike – was the only bolthole on this splendid patch of the Great Barrier Reef. But earlier this year a holiday home was unveiled on the island’s west coast. Rising from a granite bluff, the house is a bold study in modernist design. There may not be another high-end beach bungalow like this one anywhere in the world.

At first, the aesthetic marvel projects an air of tropical brutalism. It’s all concrete surfaces and daring contours, garlanded in acacia, eucalypt and pandanus. On closer inspection, the austerity of this concrete citadel dissolves. As you enter up a staircase, you’re dazzled by its convivial interior comprising an open-plan kitchen and living area, complete with an outdoor dining alcove. Windows slice through the brawny structure, suffusing it with sunshine. Another softening aspect is the judicious deployment of New Guinea rosewood, whose exquisite honey colour and swirling grain fills in doorways, cabinets and beds. One of the home’s three tranquil bedrooms is on this floor. Down a dramatic spiral staircase are two other suites, as well as a sitting area that spills open to an inviting terrace.

The whole thing feels quintessentially Australian: airy, fluid, and in conversation with nature. Helping you settle in is Paul Steinfort, an indefatigable majordomo who was waiting earlier at the airport with refreshments and is now explaining the workings of the place. “The glasses are here,” he says, releasing a drawer with a touch. “And, more importantly, the cellar is here.” One of the home’s knockout features is a curvilinear kitchen island. Meticulously assembled from layers of celadon quartzite, it resembles an avant-garde bracelet. Don’t get too enamoured. The house comes with a private chef and two avid attendants, so you won’t be using it much. The team are employed by Lizard Island resort, a short drive away.

The abode meshes privacy and proximity: it’s close enough to the resort for access to spa treatments and diving excursions, but removed enough to feel utterly secluded. Cosseted guests have the run of three private beaches with zero chance of rubberneckers. The next morning, Hibiscus Beach was calling me. When a yellow-spotted monitor lizard obstructed the path, a Mexican standoff ensued. Eventually, the visitor prevailed and “Gary the goanna”, as he’s affectionately known, scurried away. Hibiscus is the perfect crescent shape, with powdery sand, driftwood sculptures and piles of smooth boulders plonked at each end. Baitfish darted in the limpid water, emerald-hued crabs scuttled over the rocks and crested terns eagerly ogled their aquatic prey from above. Snorkelling out from the shore revealed an intoxicatingly beautiful underwater world. Miraculously, the island’s fringing reef has escaped the calamitous bleaching of further south.

It was these coral reefs that bedevilled Captain James Cook in 1770. One of the island’s earliest European explorers, Cook ascended the summit to spy a path through the jumble of reefs impeding his journey to the mainland. You can hike to Cook’s Look today for soul-stirring vistas, or you could take one of the inland walking tracks to encounter shell middens shaped over thousands of years, evidence of ancient feasts and ceremonial rites, along with stone artefacts. “Lizard Island has a long Indigenous history stretching back 6,500 years and a beautiful calmness,” Leon Pink, the resort’s general manager, told me. The Dingaal traditional owners, who consider the location a sacred place, reserved it for the initiation of young males and for the harvesting of shellfish, turtles, dugongs and fish.

The bucolic island was declared a national park in 1937 and a marine park along with its satellites in 1974. The antecedents of the resort, and by extension the house, date back to 1967, when the state government called for expressions of interest to transform this utopian spot into a tourist facility. Developer John Wilson, aligned with a consortium, had an ambitious plan. “He wanted to build a rugged nature lodge in a new Australian design vernacular,” says his son, Steve Wilson. “He built it, ran it, expanded it, and sold it in 1982.” (Andrew “Twiggy” Forrest bought the island for $42 million last year, and it’s managed by resort operator Delaware North.) Shrewdly, the senior Wilson carved off a sub-lease for a coastal cabana. The younger Wilson kickstarted the process in 1990 and contended with 32 years of red tape, seesawing approvals and litigation to bring it to triumphant fruition.

“It’s the best block of land on the reef – the Bennelong Point of the Great Barrier Reef,” he says. The project is a deeply personal one: Wilson, an entrepreneur with an extensive background in the investment industry, spent pivotal moments of his childhood here. Lesser mortals might have quit, given the seemingly insuperable obstacles, but he is nothing if not tenacious – along with his wife, Jane, he is also restoring a heritage-listed mansion in Brisbane.

On Lizard Island, Wilson was abetted by an architect who shared his vision for a robust hideaway, one that could harmonise with nature and also withstand it. James Davidson is the intrepid principle of JDA Co, a Brisbane practice known for designing smart, climate-resistant buildings. This undertaking required a mix of cyclonic moderation and hedonic abandon. “It’s a beautiful site, but it’s on a peninsula battered by strong winds, rain and sun,” Davidson says. The resort sustained significant damage from Cyclone Ita in 2014.

First came the self-contained timber cottage, adjacent to the main house, five years ago. Initially, with no approval for an access track, its construction posed a riddle. The canny pair barged materials to the main beach, transferred them on a raft to Hibiscus and then hauled them up onto the site. In a sustainable touch, solar panels on the cottage channel energy to the house. For the main dwelling, they set up a concrete batching plant to minimise truck movements. The spiriferous staircase, a construction feat in its own right, brings to mind a giant nautilus. Interior walls display a faux bois texture that adds warmth. Aside from appearing elegant, the rosewood is hardy enough to resist buckling and warping. Perforated copper louvres, which shield parts of the exterior from debris, will patinate over time, melding with the vegetation. Cantilevered elements create shade and mimic the prow of a boat. And the rooftop, with its metal handrails and sleek jacuzzi, evokes a superyacht. Up here, the biblical sunsets are polychromatic stunners.

“Nature has blessed us, so we said let’s build this strong, sculptural form and use that as a frame of endless views – you can get lost in them,” says Wilson. I was perpetually transfixed by both panoramic vistas and architectural gestures. An oculus above the staircase even functions like a clock by recording the passing of the day. Another marvellous scene came from my outdoor tub – each room has one – when a soft precipitation descended and local pheasant coucals uttered their eccentric oop-oop sound. “The key part is its total privacy,” says Wilson. “No one can see you and you can be as free and open as you want.” His favourite vantage point is looking in “from a small dingy off the beach”. Glimpsed from the water, the house recalls a Bondian lair, a slick convergence of concrete, copper and glass.

Lounge lizards take note: comfortable perches abound. The playful furniture selected by interior designer Sophie Heart includes Edra sofas, B&B Italia tables, Dedon folding chairs and Patricia Urquiola Gogan armchairs. In the garden room is a bespoke lounge upholstered in an aqua fabric, adjacent to a yellow painting by Fiona Omeenyo. Echoing the island’s spiritual presence are galvanising Indigenous artworks that animate the house. In the master bedroom, a monumental painting by Susie Pascoe floats above the bed. Pastel-hued concrete cups and dishes are a light-hearted nod to the industrial structure. The home is superbly accoutred with a smart system for adjusting lighting, music and embedded screens. Guests can summon a Riviera motor yacht for snorkelling at nearby Clam Garden, Cod Hole and the Ribbon Reefs, where you can work up an appetite.

Over the course of my stay, chef Kyle Dixon, a softly spoken English native, served a flurry of exceptional meals. The resourceful cook poaches flawless eggs for breakfast, makes pasta from scratch, and serves his own shallot and garlic relish that deserves to be bottled. Guests are encouraged to share their preferences before arrival. I eat everything except lizard, so I was delighted with his choices. One standout dinner involved barbecued painted crayfish infused with fermented chilli, butter and garlic. Dixon served it alongside grilled eggplant with harissa and radicchio salad topped with gouda. On our last night, Steinfort set up a table on the beach. When a squall arrived, he bolted into the darkness to fetch a striped gazebo. “If you’re comfortable, I’m happy,” he says, pouring Chablis.

Visiting the Lizard Island house left me speechless in more ways than one. There was the metaphorical kind of being floored by the sublime setting, inventive design and exceptional service. And the medical variety. The night before arrival I contracted laryngitis. Luckily, a voluble friend had joined me and acted as my interpreter. Bereft of my voice, I was an antic version of Tilda Swinton in A Bigger Splash, but without her drop-dead stylish Dior get-ups. Faced with a guest who relied on mime, charades and chicken scratches on a notebook to communicate, the team were unfailingly sweet and empathetic. You never know, though. Maybe it was psychosomatic. The house might leave you speechless, too.

The writer travelled as a guest of The House at Lizard Island. Rates start at $16,000 per night for two guests, with a three-night minimum, and it can sleep up to six guests. thehouseatlizard.com

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout