The evolution of cruising: a yacht in the Galapagos for 12 people

In the competition among luxury tour operators to create the most exclusive of travel journeys, a state-of-the-art expedition yacht with room for only 12 guests has emerged as the swishest way to island hop.

In the mid-1980s, Kurt Vonnegut wrote a deeply satirical, allegorical novel called Galápagos in which an ageing hustler flees the scene of his latest swindle for a luxury cruise at the end of the world. After a series of catastrophic but familiar-sounding events (a financial collapse, a pandemic) strand those aboard the ship in this distant place, the novel zooms out, and throttles forwards, over millions of years, to see that the cruisers’ descendants have evolved into something a little bit less than human. It is funny, surreal, ridiculous, and not too terribly flattering to modern-day human institutions and behaviour.

All of which makes perfect sense when you visit this island chain 1000 kilometres off the coast of Ecuador – somewhere in the middle of what sailors used to call the doldrums – the place that Charles Darwin made famous when research he’d done there spurred him on to write his masterwork, The Origin of Species. These islands have that effect on you. Rocketing you way out of your personal perspective to think in massive terms, geological eras. About human greed and pettiness. In mighty, mighty metaphors. And, at a time when everything in our lives, from technological developments to cascading natural disasters, seems increasingly like something out of science fiction, the Galápagos seem like a very reasonable destination to run away from it all.

-

This may be due, in part, to the islands’ own seeming unreality. Every landscape, vista and wildlife interaction there seemed to me, on a visit last December, aboard andBeyond’s new expedition vessel, Galápagos Explorer, to be so strange, so unique, that I found myself continually groping for analogues, in myth, in art, in hallucinatory experience. Were these chocolate fondant-like mountains of long-ago lava flows, for example, bearded as they were with miles of spectral white, bony palo santo trees, like something out of surrealism, or adaptations of Bible stories?

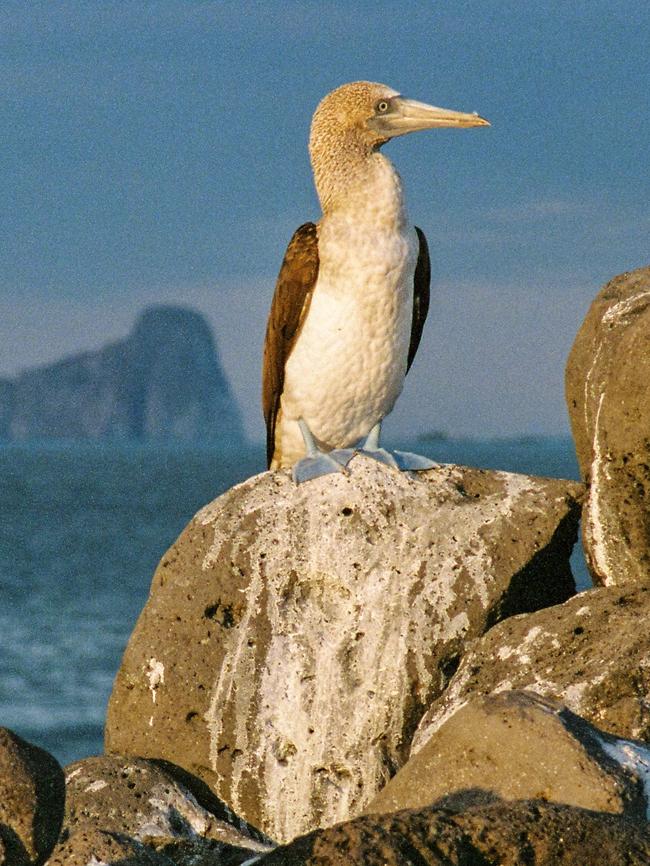

Here again I turned to Vonnegut, or Darren Aronofsky’s wildest sci-fi movies. And those black glassy beaches covered in trippy, technicolour crabs, canine-like sea lions, and brilliant white birds that looked like they were wearing mascara and nail polish applied by a child? Something out of Dali, perhaps. There, the coves of royal blue water where we swam with green sea turtles, flamingos, white-tipped reef sharks, and penguins, all at the same time? Henri Rousseau, maybe?

Again and again I wanted to place the experience in something out of the wildest fiction, in terms of surrealist context – all of these incongruous pairings of species, the improbably dreamy terrain, the inexpressibly beautiful light. But ultimately the sensory experience of the Galápagos seemed so spectacularly unlike anything else I’ve experienced, I could think of no better way to understand it than imagining I must have been wearing some sort of virtual-reality headset and exploring some ancient ecosystem – long since paved over, gone extinct. Or maybe it never even existed at all.

And that is another – perhaps the chief – reason to visit the Galápagos, for the feeling you’ll have there of the precarity of nature, of all life. The patent fragility of the ecosystem here is everywhere on display, but so too is the successful care put into its preservation. Of the 97 per cent of the islands that are designated as national park and rigorously protected as such, only the tiniest fraction less than three per cent, is ever visited by tourists.

The rest is the sole domain of nature, and visited, if ever, only by the scientists of all stripes who have in the Galápagos the single greatest active laboratory for studying the adaptability of species. Not without some surprises, as Franklin Ramirez, a longtime veteran guide and naturalist, told me. In just a single generation of some birds, scientists can witness evolutionary adaptations previously thought to take aeons – beaks growing shorter and sturdier in lean times, say, and longer and more articulate in flush.

Generally speaking, the outfits with whom you would travel to the islands will offer to take you on one of two itineraries, sailing the western islands, or those in the east (for hard-core divers, you may want to add a discursion to the north, to the islands of Darwin and Wolf, where you may find rockier seas, but some of the best underwater scenery in the world). For the rest of us exploring civilians, the closest equivalent for the day-to-day routine may be that of a safari, with a morning adventure and another in the afternoon (snorkelling or hiking or swimming amid these extraordinary places, like travelling back to Eden, where even the wildlife is utterly benign, having become so habituated to humans over the past several decades).

But if you are visiting the Galápagos, you are doing so on an expedition ship. If you are not naturally inclined to take your holidays aboard a cruise, I will assure you that the most luxurious way to experience the islands is in fact on one of these premier voyages.

The first time I came to the Galápagos, it was aboard Silversea’s relatively massive Silver Origin. And I loved it – loved the boutique-hotel-scale of the ship (with a maximum of a hundred guests and almost as many staff), but large enough to feel very calm on the sea, complete with a gym. I loved, too, the relative anonymity of being able to eat alone at one of the two restaurants, while also feeling fussed over by a personal butler. On Silver Origin, the expedition deck was a wonderful, choreographed whirl of activity and we would depart in platoons for each adventure.

So, this time around, when I travelled back to the islands, I thought I might try something different, something more intimate. The andBeyond vessel, a 38-metre luxury expedition yacht, was totally ideal – more like a sailing adventure with a gaggle of friends. There were seven of us guests, and the staff, more than double that, were the most incredible mix of naturalists and gourmands, who put on fabulous meals and then ferried us on our sorties. And on our seven-night itinerary, if we felt like pampered kids, that may have anticipated the childlike wonder we felt upon each arrival on a new island.

You may know of the Johannesburg-based andBeyond for its rightfully beloved safari camps across Africa. It has a significant and expanding footprint in South America as well (trekking the Inca trail in Peru, upscale camps in Chile, trips to Easter Island). Along with their expedition cruises in the Amazon, this is its first venture into waterborne experiences, and it is what you might expect from a premier safari outfit – if your expectations were high.

On the main deck, beyond a comfy camp-style living room, appointed with prints of naturalist illustrations, a warm, wooden-table dining room was hung with vintage maps of the islands. Most meals were served here, and all of them truly exceptional, on artisanal flatware and crystal stemware. I, sadly, became a bit notorious among the staff for wanting to eat everything at every meal, because each dish was so good and I didn’t want to miss a bit of it: a variety of creamy, silky local ceviches, as well as the more citrusy Peruvian versions, grilled whole fish, seafood soups, wonderful Galápagos-grown beef and lamb.

From the main deck, a spiralling staircase led down to the surprisingly spacious cabins and suites, six in total, which were both thoughtfully efficient (with places to tuck glassware, say, to keep items from shifting with the movement of the sea) and beautiful – wallpapered in botanical prints, and accented with Ecuadorian textiles. Up one flight from the main deck, the bar and covered lounge area was a favourite gathering place for lunchtime seafood barbecues and post-excursion sundowners.

The uppermost deck, with a hot tub and sun loungers, was where I went to watch a pod of maybe 500 dolphins off the coast of Floreana Island. Anywhere else in the world this would have been a show-stopping wildlife experience. Here, in the islands named for the antique, leathery-looking giant tortoises (from galápago, an old Spanish word for turtle), which still lumber around the island of Santa Cruz in huge numbers, a place of astonishing biodiversity, it was just filed away with a slew of others.

-

One of the ways in which the national park works to control wear and tear on the islands and their various animal inhabitants is to limit the number of visitors allowed on any one site at a time. This means that, when travelling with a bigger group, an excursion may book up, and you might have to settle for an alternative offering (an afternoon on the beach at Pinnacle Rock on Bartolomé Island, say, rather than the snorkelling in a nearby bay you were hoping for). We never had that problem on Explorer, and never really ran into other groups on nature walks or swims. Which makes for an incredible feeling of exclusivity.

I expect that my cruise mates and I were fairly typical of the fellows you might meet on Explorer (a travel writer; a wildlife photographer; a Hong Kong-based tech developer and his wife; a Chilean family; and an Ecuadorean travel agent). But because of this private-tutor sort of masterclass in wildlife, each of us seemed to take quantum leaps of understanding about various species, about the utterly bizarre local flora, about local lore and the history of the archipelago with each of our excursions. About ourselves, even, and about one another.

This bonding with our fellow cruisers, and with the incredible guides and staff, piled up to pack quite an unexpected emotional punch. So that, after a week on board, and swimming with sharks, floating with sea lions, drinking the finest wines in the world, I stepped back on shore feeling not only like a wizened old naturalist and super explorer, but like I’d made lifelong friends, with the memories to match.

The writer was a guest of andBeyond, which hosts regular seven-night departures on Galápagos Explorer; cabins from $US10,950. andbeyond.com

This story is from the April issue of Travel + Luxury magazine.

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout