The evolution of business class

Business class travel has come a long way since its conception in the late ’70s. Travel + Luxury pores over the archives to chart the evolution and future of premium flights.

Australians are world experts in long-haul travel. Our carry-on bags are packed with precision, containing essential items for surviving multiple stopovers, 13 per cent humidity and brutal jet lag. A 14-hour flight to Los Angeles? No problem. Economy flights from Melbourne to Greece with two stopovers? Easy-peasy.

Our airline staff are even more impressive travellers, circumnavigating the world while still managing to smile through interactions with problematic passengers, distressed infants and vegan or gluten-intolerant travellers who forgot to pre-order their meal.

“The distance is nothing to us,” says Annie Oeding, one of Australia’s first female flight services directors, who began her career with Qantas in the early 1970s.

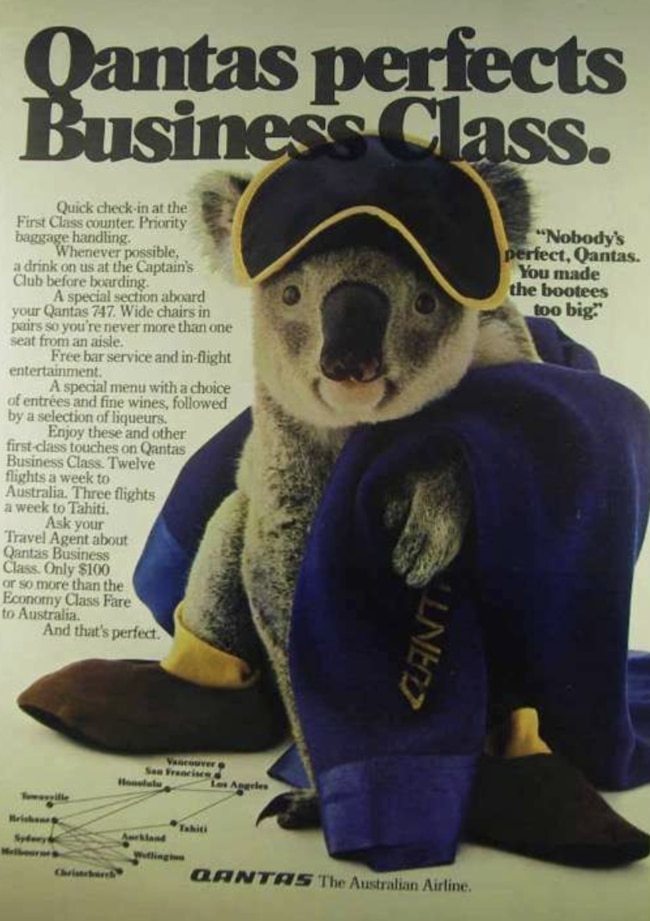

It shouldn’t be surprising, given our collective proclivity for international travel, that Qantas takes credit for inventing business class, that comfortable cabin inserted between the ultra-luxurious amenities of first class and the no-frills squeeze of economy.

It’s a contested claim. In the years before 1979, when Qantas officially launched “business class” on its Boeing 747-238s, other international airlines had begun spruiking a more comfortable alternative to economy, or “tourist class” as it was known, for passengers willing to pay a premium. In 1977, Thai Airways promoted a “closed-off section between first class and economy” called business class on its DC10s. The layout, however, remained similar to economy seating and resembled what we know today as premium economy. British Airways, Air France and Pan Am had also started developing a premium product, sitting full fare-paying passengers at the front of the economy cabin and offering perks such as priority boarding, lounge access and superior dining options to those served to travellers on discounted economy fares.

What is indisputable, however, is that Qantas’s iteration – a cabin designed with a 2-4-2 seating configuration plus all the aforementioned benefits and a dedicated airport check-in desk – was the closest to the business class we know today.

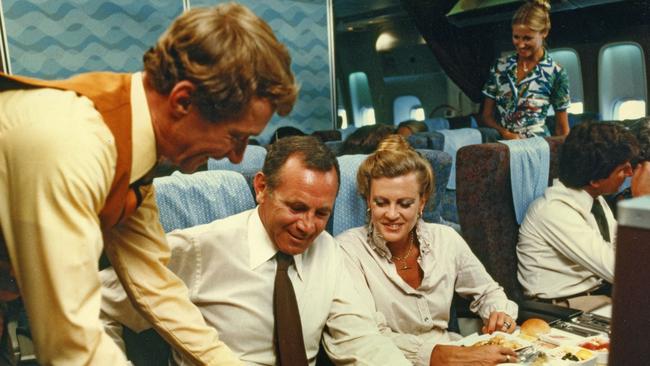

Oeding witnessed the evolution of premium seats during her time working as an international flight attendant. It was a gradual process, she explains, as airlines realised a growing need to cater for business people and politicians, who flew frequently.

“What Qantas tried to do on the 747s was create an area we called the B-Zone, which was the area behind first class,” Oeding explains. “They were economy class seats, but we tried to give passengers an extra seat between them when we could.”

Before the frequent flyer system was introduced, airline staff were tasked with manually identifying passengers who were regular travellers and paying full ticket price.

“In the early days, we always had a passenger manifest and there would be notations, which were basically hand written or came out on Roneo machines [a precursor to the photocopier]. We’d get people coming through the doors who would say ‘Can I get an upgrade?’, and try to persuade you they were a frequent flyer. We would just show them this three-foot-long list that said ‘frequent flyer’ beside passengers’ names.”

Once the legitimate VIP passengers were identified, Oeding says staff would try to make their experience extra special. “We’d ask them things like ‘Would you like a complimentary glass of wine?’, without trying to ignore the person beside them who had probably scrimped and saved to get a seat.”

In the early ’80s, an advertising stoush began between airlines rolling out the new passenger category. The now defunct US airline Pan Am, which in the late ’70s introduced Clipper Class to its fleet – an option for full fare-paying customers that included free drinks and lounge access – took aim at Qantas’s higher business class fares via a series of print advertisements.

“We don’t think anyone should have to pay a 15 per cent surcharge to go to America,” one of the airline’s ads proclaimed. “So one thing’s for sure. Fly Pan Am Clipper Class from say, Sydney to Los Angeles, and you’ll be at least $100 better off at the other end.”

Qantas retaliated, comparing its spacious business class seating to the first class seats of its rivals, stating they were in many cases comparable.

By the mid-’80s, most of the world’s major airlines had taken Qantas’s lead, fitting out aircrafts with exclusive cabins featuring spacious seating, more leg room and better aisle access. The cuisine was also of a higher standard than in economy, but convenience-style food and tray service remained de rigueur until the mid to late ’80s.

“I remember, for example, business class passengers were given little celluloid packs of four oysters, and of course they still received a tray,” Oeding recalls. “I personally preferred putting a tray down because it gave us that little extra time to spend with the passengers; it wasn’t such a rush to get things out.”

It wasn’t until the new millennium that business class underwent its first major shift. Towards the mid-’90s, airlines such as British Airways had switched reclining lounge-style chairs in favour of cradle seats, which provided more leg and foot support for long-haul flyers.

But in 2000, BA debuted the first fully reclinable flatbed, until then a luxury afforded only to those paying top dollar for a first class ticket. Developed by London design firm Tangerine, the new BA Club World cabin accommodated eight seats to a row in an opposing configuration on the airline’s B747s. In order to achieve BA’s requirement that at least seven seats needed to be retained per row to stay profitable, the team had to position some seats facing towards the rear of the plane, a concept some passengers disliked. To make the idea more appealing, engineers placed the reverse-facing seats by the window, giving the backwards-facing passengers a prime position. It was a hit, and the design is still in use by some carriers.

Sarah Johnson, senior curator at the Qantas Founders Museum, says when it comes to the history of air travel, “There has always been this intersection between luxury and cutting-edge design.” Johnson cites Marc Newson’s Skybed, Qantas’s first fully reclining business class seat, which the industrial designer developed for the airline in 2001, as a perfect example.

Shortly after the innovation was unveiled, Newson was tasked with designing the interior of the Qantas Airbus A380; everything from the soft furnishings to the fine bone china and glassware used in business class cabins. Johnson notes that these items, as well as business class menus and the first versions of Peter Morrissey’s logo pyjama sets, have become collector’s items among aviation enthusiasts.

With oversized entertainment screens, chef-prepared meals and soft bedding, today’s business class offering far exceeds even the plushest first-class cabins of the ’80s and ’90s.

“There have been so many enhancements to business class in recent years,” says Michael Schischka, general manager of Mary Rossi Travel. The growth of the category, as well as that of premium economy, is a reflection of travellers’ demand – and willingness to pay a premium – for a comfortable in-flight experience.

“When you consider that most international flights out of the country are at least nine hours, comfort is a huge factor for Australian travellers,” he adds.

The aviation industry was a major casualty of the Covid pandemic. Data from McKinsey Global Institute estimates airlines collectively lost about $162bn in 2020. Rather than let their aircraft gather dust, many took the international travel disruption as an opportunity to upgrade and refit their fleets.

Emirates is pouring $US2bn ($3bn) into a major retrofit of 120 of its planes, a process that began this month and will include a complete business class cabin overhaul on its A380 and Boeing 777 aircrafts. Finnair is also refreshing its Airbus product; likewise United with the Polaris cabin. Australian flyers had their first taste of the new British Airways Club World offering in October. The list goes on. In June, Air New Zealand announced plans to roll out a new class within its business category, the Business Luxe suite, which includes sliding partitions for privacy and a “buddy seat” that allows two passengers to dine together.

Companies at the forefront of aviation interiors are banking on sustainability, privacy and interconnectivity as areas in which passengers will see the biggest changes in the business class cabin in coming years.

Lydie Blanque, strategic product marketing director of cabin interiors at Stelia Aerospace, says frequent flyers on Airbus planes may soon have their seats pre-programmed to individual preferences.

“Airbus’s future cabin will be connected thanks to a platform enabling real-time interconnection of core cabin components,” she explains, adding: “We strongly believe passenger wellbeing and predictive maintenance will be two game changers in the future moving towards a unique, feel-at-home journey intermingling emotions and experiences.”

There seems to be no end to how airlines will seek to out-do one another in the lucrative passenger-pampering stakes. Some of Qatar’s QSuites in the centre of its business class cabin can be configured into a double bed; Emirates and Etihad have snazzy onboard bars. There’s Saks Fifth Avenue bedding, Armani/Casa crockery, pyjamas by Zimerelli and The White Company, and beauty potions from the likes of Bulgari, Neal’s Yard Remedies and Clarins, luxuriously packaged in pouches by brands such as Globe-Trotter, Marimekko and Bric’s.

In that rarefied space beyond the economy-class curtain, things can only get better.

Sky-high fine dining

No one is better placed to track the evolution of business class cuisine than Neil Perry. In his 25-year tenure as Qantas creative director of food, beverage and service, Perry has both witnessed and influenced the huge changes in in-flight food.

“Back in 1998 when we first started in business class, they used to wheel out a big casserole dish into the cabin and serve customers with tongs directly from that,” Perry recalls. “We were the first major airline to move to having our cabin crew plate up individual plates in the galley and carry them to the customer at their table.”

The restaurateur, who last month celebrated the silver anniversary of his partnership with the airline, admits the transition from cart service to plated dishes was a big change for crew at the time.

“We have got better and better as our crew have become more experienced at this kind of service, and it’s testament to not just the quality of crew but their enthusiasm to make the effort to ensure the food is beautifully presented.”

Perry says Australians’ love for international travel and multicultural cuisine is a driver for his team to offer a wide variety of options to passengers.

“Business class travellers, in particular, over the past 30 years have become even more worldly and sophisticated. They stay in great hotels around the world, they eat in beautiful restaurants so we make sure we deliver something in the air that is absolutely restaurant quality.”

In-flight wellness and Qantas’s upcoming Sydney to Europe non-stop flights are two major factors driving the next iterations of business class cuisine, according to the chef. In 2017, the airline embarked on a research project with University of Sydney’s Charles Perkins Centre to study the impacts of long-haul flying.

“It’s really exciting stuff,” Perry says. “(It) means we will continue to investigate what relationship food and beverage has to in-flight wellness, jet lag and hydration. From what ingredients we use, to what time we serve particular meals, it will all be about maximising the feel-good factor both on the palate and on the body.”

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout