The cheat’s way to do the most famous walk in the world

Some pilgrims do the 800km Camino de Santiago carrying their own gear, others take guided tours, this route is a more gentle approach and involves lots of local food and wine.

Some days on the road are so perfect I wish they might never end. When the sun is soft, and the path fringed with wildflowers and grasses shoulder high. When all around flaxen fields of wheat are embroidered with poppies like vermilion threads.

When in the distance an ancient church floats like a marooned ship and the only sounds are the wing beats of startled birds and your own footfall.

With fellow travellers, I am in northwest Spain, congregating in the ruins of an 11th-century monastery, welcomed by a friendly dog with a small scallop-shell motif, emblem of the Camino de Santiago, attached to its collar.

An albergue, or hostel, slots into the towering ruins, cafe tables are set in the roofless nave and transept beneath a peerless blue sky. Full disclosure. I am not walking the Camino. Not properly. Not yet. But I am making a quick reconnaissance, dipping in and out, walking a few kilometres here and there, sampling the mood, the food, the road and beauteous landscapes of Spain. Meeting the pilgrims.

I’m relying on my new friend Iona for practical insight. She has made the pilgrimage twice, once from Portugal, once from France. Because the Camino de Santiago is not one route, but a network forged over mountains and through forests by Catholic pilgrims as long ago as the early 9th century. Battling disease, wolves and bandits, they came from all corners bound for the cathedral in Santiago de Compostela built over the tomb of the apostle Saint James. We’re exploring a section of the most popular route, the Camino Frances, or French Way (also known as the Way of St James), which commences in the French Pyrenees and winds for some 800km through beautiful countryside and ancient cities. On fence posts and street corners, yellow arrows and scallop emblems point the way. (If that distance sounds daunting, you need walk only the final 100km from Sarria to qualify for a certificate, collecting stamps in a passport as you go.)

My journey begins in Burgos in Castilla y Leon, a soulful region home to the longest stretch of the French Way (380km). We are bunked down in a small hotel with a rather ecclesiastical vibe (dimly lit and a bit musty), opposite an astonishingly beautiful UNESCO-listed Gothic cathedral crammed with treasures including Flemish paintings, gleaming chalices and a great central lantern beneath which lie the mortal remains of El Cid. Burgos is a lovely city. The old road linking France to Madrid is lined with plane trees clipped in the French fashion, and little restaurants where the preferred aperitif is not sherry, but vermouth served in a martini glass with olives.

Throughout the afternoon, pilgrims drift into the albergue near the cathedral dossing on bunks or washing dirty Camino togs to hang on the terrace to dry. Others are enjoying a wine in the bar opposite (no vino no Camino is a widely accepted pilgrims’ axiom). These hostels are found all along the French Way. Cash only. One night only unless injured. Some have private rooms. (Other walkers prefer to book hotels or join fully supported tours.) While the pilgrims turn in early, our merry little band of interlopers is out late sampling the edgy fare of local celebrity chef Isabel Alvarez at En Tiempos de Maricastana. Think: Thai-inspired croquetas and a sort of smoothie made using local red beans, an intensely regional product with only 500kg grown each year, served with olive oil ice cream.

Next morning, we set out on foot into a landscape virtually unchanged since medieval times. Every sun-kissed village, no matter how small, has an enormous church, often Romanesque, sometimes topped with gargantuan stork nests, half a dozen birds decorating the roof like elegant gargoyles. That marooned ship of a church turns out to be 13th century; cresting the threshold there’s an Indiana Jones moment as we tiptoe into the dark soaring interior with its Gothic crypt and magnificent altarpiece. On we stride, into the village of Castrojeriz, which, like many, grew up along the Way and today relies heavily on pilgrim foot traffic.

The village is deserted; there was a festival yesterday and everyone is having a lie-in. We find a cafe open on the town square and plop in the sun, ordering a cafe con leche before chatting with foot-weary pilgrims as they drift into town. Next port of call is the beautiful city of Leon, but not until we sit down to another late, long lunch (it’s the Spanish way). We have suckling lamb and Cecina, a cured beef like the Italian Bresaola, at a long timber table in Hotel Real Monasterio de San Zoilo, a restored monastery.

I’d walk from France to Leon just to visit the beautiful 13th-century cathedral; the wonderful stained-glass windows celebrating the trees and plants of the region are reminiscent of the work of William Morris. The great stone front gate is less appealing, depicting the final judgment; bishops and men of import are heaven-bound. Others, mostly women, are being popped into pots of boiling water or fed to demons. On a lighter note, Leon has a lively old town with loads of tapas bars and an interesting building by Gaudi.

From Leon we travel to the highest point on the French Way, the iron cross or Cruz de Ferro, at 1500m. The landscape transforms swiftly as we climb from the golden plains of Castilla to mountain forests of holm oak and chestnut trees and meadows laced with foxgloves.

Along the way, pilgrims’ cafes serving homemade empanadas and red wine are wedged into low stone buildings tucked into the steep roadside.

A quick stop is made to explore the storybook hilltop castle in Ponferrada. The Knights Templar were based here in the 13th century to protect pilgrims from bandits and other miscreants. This was a time before comfy HOKA walking shoes and moisture-wicking T-shirts. Back then the look was more scratchy robes, and a water or wine-filled gourd slung across one shoulder. Before the Knights Templar, the Romans were here busily dismantling mountains to mine gold at the nearby UNESCO-listed Las Medulas, today an otherworldly, russet-red landscape well worth a detour.

Green hills and mist-filled valleys announce our arrival to lovely Galicia, home to the best food along the entire Way, according to pilgrims. The first Camino milestone is the pretty village of O Cebreiro. A chap playing a Galician gaita or bagpipe (Galicia has Celtic roots) greets walkers. Traditional pallozas (circular stone houses) are interspersed with little restaurants. Octopus empanadas are popular. The local church is enchanting and important for many reasons, but especially because in the 1980s parish priest Elias Valina Sampedro is credited with reviving the Camino, travelling its length painting yellow arrows for the modern era’s newly minted pilgrims to follow.

We join the trail again on foot, and pilgrim numbers are building, a steady stream flowing through green fields and dappled forests towards Santiago de Compostela. Breaking for coffee in the garden of a busy cafe, we’re joined by a group of well-dressed walkers carrying small packs just large enough to accommodate an energy drink and lipstick.There is a definite Camino pecking order, hardcore pilgrims walking 800km carrying their own gear, dossing in hostels on disposable sheets, and those staying in smart hotels with support vehicles. There is no judgment among walkers apparently ... or not much. But we’re lucky enough to be dossing in lovely Hotel As Torres da Hermida, a 300-year-old restored manor house tucked down a country lane with gorgeous meadow and forest views. I have an 18th-century bread oven in my otherwise contemporary room. Always handy.

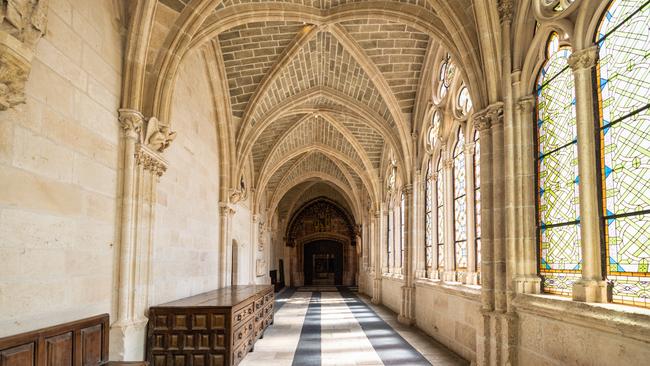

This lovely building is typical of the incredible architecture all along the Camino. Especially atmospheric is Monasterio de San Julian de Samos, dating from the 6th century. It’s a vast, echoing complex, once one of the most important cultural centres in Europe, today home to fewer than 10 Benedictine monks. Accommodation is available here for those seeking a retreat. And there’s a charming gift shop manned by the monks where I buy several boxes of homemade chocolates and biscuits so holy that they’re surely kilojoule-free.

Back into that stream we dive, now veritably thundering with pilgrims. With the cathedral and end in sight, the pace is quickening.

Everyone walks their own Camino, at their own pace, but everyone ends up here, in the cathedral square, where emotions spill over. Weary walkers cry and embrace, cheer wildly or simply rest on their packs, contemplating the impressive cathedral. Some have ridden bikes; others have travelled with their dog. An 80-year-old French woman whom we passed a day earlier, bent double under her pack, slowly hobbles into the square. Everyone has a story, and most say they are changed, sometimes profoundly, by stepping away from the 21st century to follow in the footsteps of medieval pilgrims for two to three weeks. Friendships are made, lives reset.

Unsurprisingly, the elaborate Pilgrims mass held in the cathedral twice daily takes on special meaning (arrive an hour early if you want a seat). We’ve heard a rumour that today the priests will be deploying the famous Botafumeiro, a giant incense thurible. Hoisted by half-a-dozen robed men and trailing fragrant smoke, it swings in a great ceiling-scraping arc in front of the main altar and is hugely impressive. Even visiting nuns are whipping out their mobile phones to record the moment. I recommend booking a tour that takes in the cathedral’s vast roof and tall tower. There are many steps and it’s slightly vertigo-inducing but the far-reaching views are wonderful.

Walk over, it’s time to eat. Our guide assures me the Galicians consume more seafood than anyone except the Japanese. In the historic markets, an entire hall is devoted to seafood vendors. Another is lined with little restaurants where chefs are happy to prepare the fish you purchase next door. Check out Abastos 2.0 with its daily-changing market menu of delicious seafood, such as little cockles with lime, flash-grilled razor clams, and crispy empanadas with hake.

The city’s swankier restaurants include the moody, groovy Indomito, opened last December by Martin Vazquez, the first chef in Galicia to earn a Michelin star. The fantastical desserts are outstanding. Restaurant Gaio is also very good, offering Peruvian/Asian fusion fare: mackerel gazpacho, John Dory ceviche, sheep’s milk creme caramel.

But my favourite food moment is more modest. It’s a small brown cardboard box of shortbread biscuits purchased from a nun through a tiny hatch in the wall of the convent in the old town. A heavenly end to my first taste of the Camino.

In the know

Walking tours of Camino de Santiago are available from Australian and international tour companies. Check the Spain Tourism Board, Xunta de Galicia and Junta de

Castilla y Leon websites for itineraries, accommodation tips and further details.

Christine McCabe was a guest of the Spain Tourism Board, Xunta de Galicia and Junta de Castilla y Leon.

If you love to travel, sign up to our free weekly Travel + Luxury newsletter here.

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout