The best place to get custard tarts in Portugal

Stunning royal palaces, one of the world’s oldest universities and of course, local food – here is our guide to visiting Portugal.

‘It is up, always up,” the Portuguese guide says, gesturing at the ancient cobbled street winding its way skywards. He is not our guide but someone else’s, and they are on their way down.

We are in the riverside city of Coimbra in central Portugal, home to one of the world’s oldest universities, which is our destination this morning. Founded by King Dinis I in 1290 in Lisbon, the university was relocated in 1537 to a royal palace on top of a hill in Coimbra and is now a UNESCO World Heritage site.

My wife, always suspicious of my map-reading skills, is reaching for her phone in anticipation of an Uber ride, but pride is at stake and I insist on walking. “He told us to just keep walking up,” I say, scouring the terracotta rooftops for anything that looks like a university. “How far can it be?”

A better question would be “How steep can it be?”; it’s not called Rua Quebra Costas (Backbreak Street) for nothing.

After more steps and another vertiginous bend we finally arrive at an ornate staircase leading to the university’s main courtyard, a shimmering white plaza with breathtaking views over the town and the Mondego River far below.

It is the end of term and graduating students waft around the courtyard, smiling but vaguely sinister in their billowing black capes. Walking around the university is free but to see inside its greatest treasures – such as the university’s exquisite chapel, the Capela de Sao Miguel, which dates back to the 11th century – you will need to buy a ticket for €12 ($20), with timed entry to the sumptuous Baroque library, one of the richest in Europe.

Completed in 1728, the library – also known as the Joanina Library in honour of King John V, who authorised its construction – is the finest surviving example of Portuguese Baroque, exemplified by its fabulous painted ceilings, gilded oak bookshelves and intricately carved internal balconies.

Conceived essentially as a vault for the conservation of its priceless collection of books, the library was built with walls 2m thick. Six massive tables inlaid with Brazilian hardwoods are covered each evening with leather mats to protect them from a colony of insect-eating bats that lives somewhere up in the rafters. No photographs are allowed inside the library, perhaps for fear of waking the bats before the mats are down.

Walking back, we realise we are not the only ones bamboozled by the snakes and ladders of Coimbra’s medieval old town. The narrow cobbled streets are full of tourists squinting at their phones. A black BMW comes to a halt beside the cathedral and a small crowd gathers to watch as it squeezes between two stone pillars, nearly losing a wing mirror in the process. Google Maps will tell you the name of any street in Portugal, but it won’t tell you how wide it is.

That evening a tip-off takes us to Ze Manel dos Ossos, which translates as “Manel of the bones”, a tiny restaurant in a narrow alleyway near the river. The menu is in Portuguese and the walls are adorned with animal heads and horns and notes from appreciative diners. The whiskery black head of a taxidermied wild boar scowls at us all night; it might be the ancestor of the animal that went into our delicious boar and bean stew.

The restaurant’s signature dish, a legend online, is a rustic plate of pig bones. If bones are not your thing, there is always fish, but when we attempt to order it our waiter counsels us darkly, “You come to Manel for meat, not fish.” He’s right, of course. Cod you can find anywhere in Portugal, but you have to come to Manel for the bones.

Our Portuguese holiday began not in Coimbra but in Lisbon, the City of Seven Hills, a metropolis even more undulating than San Francisco. As locals joke about San Fran, if you ever get tired of walking around Lisbon you can always lean against it; Porto, the country’s second city, is worse.

In both cities the high points are dominated by castles, forts and churches, which have battered walls and hybrid architecture that tell the story of the Reconquista, the 13th-century Christian reconquest of Portugal after five centuries of Moorish rule. King Dinis was the first king to rule a Portugal at peace after the upheaval.

As well as building a wall, named after himself, to defend the riverside area of Lisbon, Dinis left his fingerprints on Castelo Sao Jorge, the castle that looms above the city’s historic centre. Legend has it that a Christian knight, Martim Moniz, finding one of the castle doors left open, hurled his own body into the breach, preventing the Moors from closing it and enabling his fellow knights to seize the castle.

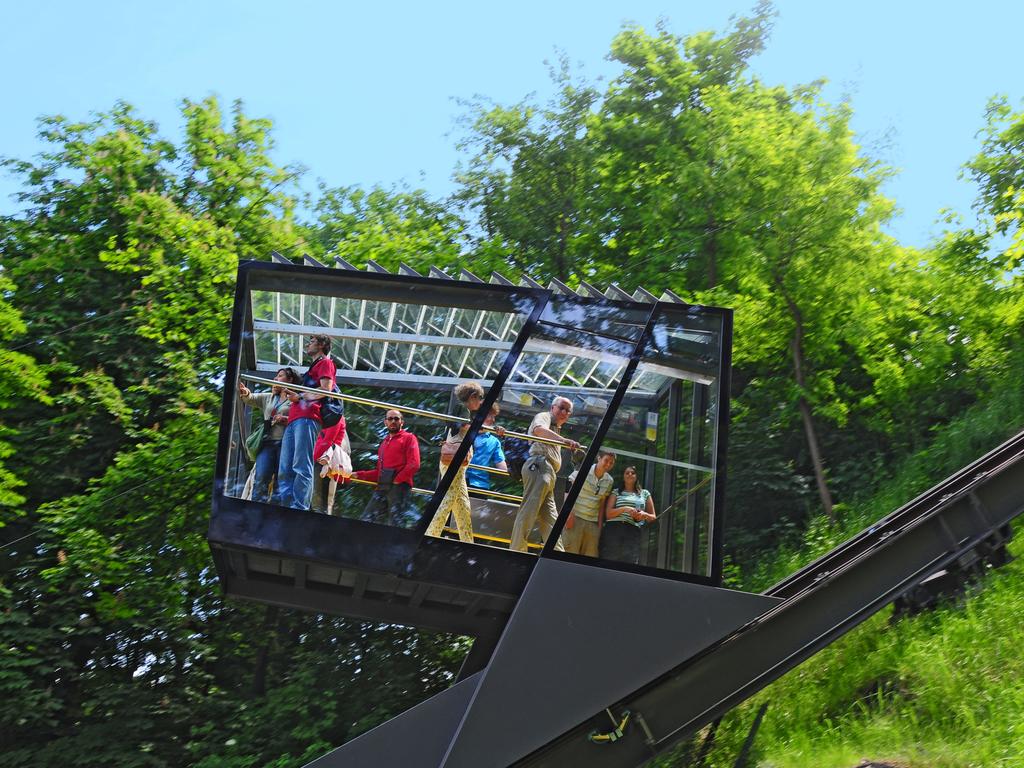

Moniz has fittingly given his name to the city square at the base of the hill from which visitors today can catch an outdoor escalator, the Escadinhas da Saade (stairway of health), one of several levitating devices installed to meet the challenge of Lisbon’s seven hills.

Another is the historic Santa Justa lift, a wrought-iron structure built at the turn of the 20th century in a style reminiscent of the Eiffel Tower. Once an integral part of the city’s public transport system, the Santa Justa lift is now one of Lisbon’s most popular tourist attractions. A ticket to ride in one of the elegant polished wooden cars costs about €5 but the queue can be a turn-off.

Raoul Mesnier du Ponsard, the Portuguese engineer who designed the Santa Justa lift, also designed Lisbon’s three funicular railways, all built between 1884 and 1892. The most popular of the three, the Elevador da Gloria, goes to the bohemian Bairro Alto district; the ride only lasts a minute or two but the view from the San Pedro de Alcantara lookout is spectacular.

Still on the trail of King Dinis, we catch a train to Sintra, a town in the foothills of the Sintra mountains that served as a retreat for Portuguese kings and queens until 1910, when the monarchy was overthrown and replaced by the first republic. Nestled among precipitous peaks, the old town of Sintra is another UNESCO World Heritage site.

The sun is shining as we pick our way through the gaggle of electric tuk-tuk drivers hustling for business outside Sintra’s nondescript railway station. The road into town meanders gently downhill, then back up to the Palacio Nacional de Sintra, originally a Moorish palace before King Dinis set to work transforming it. The 33m-tall conical chimneys built in the 15th century to serve the palace kitchens have become a symbol of Sintra.

Outside the Palacio Nacional more tuk-tuk drivers loiter, hoping to discourage us from attempting the steep, 2km walking trail to Sintra’s 10th-century Moorish castle. Seized from the Moors by King Afonso I in 1147, the castle once dominated both the surrounding territory and the naval approach to Lisbon. Snaking along razorback mountain ridges and often obscured by clouds, the moss-covered battlements afford brilliant views across the coastal plain to the Atlantic.

Nearby, on Cruz Alta, the highest point in the Sintra mountains at nearly 550m, sits the crazily colourful Palacia National da Pena, a whimsical eruption of 19th-century Romanticism built on the site of a medieval monastery. With its red and yellow towers and ornamental battlements, it looks like an outsized entry for the Royal Agricultural Show cake competition. Inside the palace, everything is as it was in 1910 when the royals fled to Brazil to escape the revolution.

Our final stop is Porto, where even the city tramlines look like funicular railways. Prince Henry the Navigator was born here; perhaps he went to sea to avoid climbing all those hills. The guidebook recommends climbing the Baroque Clerigos bell tower, at 75m the tallest in Portugal, but in this wickedly undulating city the 225-step spiral staircase feels like 224 steps too many and we opt instead for a beer in a parkside cafe.

We spend our last day cruising through the beautiful Douro Valley, one of the world’s oldest wine regions (also UNESCO World Heritage listed). British wine merchants came to the Douro in the 17th century after a trade spat with France prompted King Charles II to ban the importation of French wines. The Douro’s terraced hillsides, densely planted with vines, remind me of the rice paddies in Java; hardly a square metre is uncultivated. Around every bend in the river is a hill and on top of every hill is a wine estate.

But in Portugal even the rivers have to be climbed, and over the course of several hours the boat rises a total of about 70m through a series of gigantic lock gates before arriving at the pretty village of Pinhao.

Back in Porto, we have only one climb left – to our eccentric attic apartment on the fourth floor. Wherever you go in Portugal, it is up, always up.

Tom Gilling travelled at his own expense.

If you love to travel, sign up to our free weekly Travel + Luxury newsletter here.

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout