Skiing in Arlberg, Austria

With powder coating the landscape and bustling bars to recover in, Austria’s epic skiing and apres-ski scene is just as you left it.

In the winter of 1895, a parish priest from the Austrian mountain village of Warth received in the post a rather cumbersome package from a clerical colleague in Scandinavia. It was a pair of thin wooden planks, measuring more than 2m in length and apparently designed to be strapped to the feet. The unexpected arrival aroused the interest of the local newspaper, which reported a slight issue with these newfangled snowshoes: “No one has the scantest idea of how to use them.”

From where I’m standing now, at the top of the Kapall chairlift, 2330m high in the place they call “the cradle of alpine skiing”, it’s safe to say the people of the Arlberg have got those planks figured out. So much of how we ski today, from the lessons we take to the turns we learn to the equipment we use, can be traced back here. Looking around, you must admit they had some pretty good material to work with.

An unbroken view of snow-covered alps stretches to the horizon. Skiers plunge over the crest, carving exquisite lines 1000 vertical metres down a world cup course to the village of St Anton; others lounge on deckchairs in the sun, sipping beer or eating strudel. A golden retriever trots past, leaving pawprints in the soft spring snow. Could the scene be more European?

Geologically speaking the Arlberg is a massif, a mass of mountains. It’s also massive. Ski Arlberg resort boasts 88 lifts, 300km of groomed slopes, 250km of off-piste and 80km of cross country. A €45m ($70m) investment in four new lifts, including the 1.8km Flexenbahn cableway, has completed the missing link between the villages of St Anton, St Christoph, Stuben, Zurs, Zug, Lech, Schrocken and Warth, making this the largest inter-connected ski resort in Austria. It must have felt eerie last season, when it was open only to locals.

“We felt like sheikhs of the mountain,” our ski guide Yannick Rumler says. But even now at full capacity there’s plenty of space on the slopes, and barely a wait at the lifts.

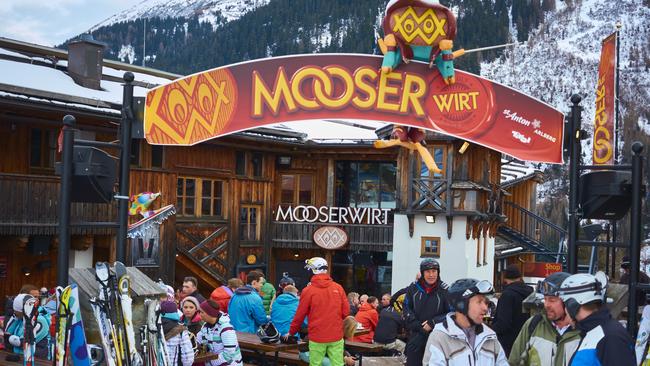

The return to pre-pandemic revelry couldn’t be announced any more empathically than at the Mooserwirt in St Anton, one of Europe’s most infamous apres-ski bars. At the slope-side entrance hundreds of skis and poles are strewn like debris from a storm surge. The music thumps and the terrace throbs as one technicolour organism, hundreds of skiers squished into a heaving, virus-taunting swarm of humanity, dancing on tables and pumping fists to the latest Euro-pop hits.

The boutique Mooser Hotel occupies the same building as the Mooserwirt, but the atmosphere couldn’t be more different. A true ski in/ski out hotel, it takes all of 30 seconds to glide from the ski lockers to the base of the Galzigbahn gondola. The hotel’s 17 snug suites pack a host of luxe touches into modest square metreage. My room has stylish wood panelling, designer furnishings and a “Swiss pine climate box” humidifier. The bathroom is a glass cubed centrepiece, privacy provided by electronic blinds (or just gaze at the mountains from the tub). It also claims to have gold standard soundproofing.

So here comes the test. There’s total silence inside my room, but as I open the door to my balcony the roar becomes deafening. It’s not the Mooserwirt, though, but a mountain stream gushing down a steep gully, swollen with snowmelt and conducting a sublime spring symphony. Of die Popmusik I hear not a peep. Incredible. I sink into my sheepskin covered balcony beanbag and soak up the late afternoon sun, the infinity pool shimmering below and the teasing foothills of the alps rearing above.

The alps are sporting a bold new look this spring, coated in orange sand blown 3000km from the Sahara Desert. A succession of bluebird days suits the desert vibes, and the snow conditions reflect the balmy temperatures: firm in the morning before softening to mushy moguls by mid-afternoon. I ditch the ski jacket and take to skiing in a T-shirt.

We quickly find the rhythm to spring skiing: hit the slopes early and ski like mad while the snow is good, have lunch on a sun-kissed terrace, then head down for apres-ski (or the hotel spa) before things get too slushy. It’s the essence of intelligent design.

St Anton attracts sporty skiers keen to test their skills on slopes used for the 2001 World Alpine Ski Championships and 2021’s Ladies Ski World Cup. Across the valley, the north-facing Rendl side is more incognito and a locals’ favourite, with terrain parks, firm-packed snow, and a glorious, long home run.

Rumler points out the Kuchenferner glacier, explaining with some sadness it’s one of only five left in a region where there used to be many. He’s hoping his future children will have the chance to see it before it is gone. Rendl also marks the start (or end) point of the 85km run of fame, a one-day traverse of the entire Ski Arlberg resort to Warth, and the longest resort crossing in the Alps.

The interconnectedness of the Arlberg means you’re never stuck repeating the same runs. Instead, you village-hop – in much the same way that a cruise ship calls in to different ports – setting course for a destination in the morning, then looping back home, or even skiing on to a new hotel in a new village, your luggage transferred ahead and waiting for you. It’s a wonderful concept.

We ski to lunch in historic St Christoph, at the crest of the Arlberg Pass, where the smell of sausages and the sound of music draws us to the Hospiz Alm restaurant, a rustic farmhouse so picture-book traditional I half expect to find the von Trapp family chowing down on a Wiener schnitzel.

In a moment of “you only live once” abandon, we skip straight to dessert, ordering the kaiserschmarrn (emperor’s mess), a scrambled pancake with rum-soaked raisins, served by a lederhosen-clad waiter on a sunny balcony fit for the kaiser himself. After lunch we tour the restaurant’s opulent wine cellar, holding more than 3000 bottles of Bordeaux and accessed via a wooden slide, to save clomping down the stairs in ski boots. I feel a bit like Willy Wonka, making my entrance, even more so when the psychedelic scale of the cellar is revealed. The baby bottles are mere magnums and the largest is a whopping 27 litres. I spot a Chateau Latour up for grabs for a cool €85,000. OK, so it’s no candy store.

We ski again to lunch the next day in Stuben, where long-time local identity Rudi Pichler joins us at the Fuxbau (Foxhole) restaurant. Pichler tells me the interlinking of the resort has done wonders for smaller villages such as Stuben, allowing guests to base themselves here and still access the entire resort.

I order what might be the savoury equivalent of kaiserschmarrn, a bowl of kasespatzle, a type of egg noodle stopped dead by an onslaught of melted cheese, topped with crispy fried onions (think haute macaroni cheese). Pichler explains the dish should only be eaten when an active afternoon awaits to work it off. He must have read our itinerary, because lunch is but a brief stop on our traverse to Lech. It’s the day I’ve been waiting for.

There’s always time though to pay our respects at a statue of Stuben’s favourite son, Hannes Schneider (1890-1955), a man who is to alpine skiing what Monet is to Impressionism. Founder of the Arlberg’s first ski school (in 1921) and pioneer of the “Arlberg technique”, a turn still taught today, no one glamorised skiing globally quite like Schneider.

We take six lifts to Lech, skiing down one valley and then hoisted up the next, each new vista somehow more breathtaking than the last, every run different and exhilarating. From the Flexenbahn gondola we gaze down on mountain goats, and from the new six-seater Madlochbahn chairlift we can almost skim the tips of our skis across the surface of the frozen Lake Zursersee, smooth as white quartz.

The peaks give way to trees, trickling streams and timber-clad chalets as we glide into Lech, kicking our skis off at the terrace bar of the Hotel Post. The River Lech is twinkling iceberg blue in the afternoon sun, the sun is shining and a celebratory round of Aperol spritz has just landed at the table; can somebody please pinch me?

On our final day we ski the famous white ring, a 22km circuit that links Lech with Zurs, Zug and Oberlech. It feels like a victory lap. Not so long ago, I wondered if we’d ever see sights like this again, and I’m not taking this moment for granted.

Lost in a reverie, I barely notice other skiers flying past. Fast lane or slow lane, we’re all having the most fun you can have on two planks.

In the know

Ski Arlberg winter season runs to about April 23, depending on snow conditions. The resort is well served by train from Zurich Airport (2 hours and 45 minutes), Innsbruck (one hour and 10 minutes) Salzburg (three hours) and Vienna (five hours and 30 minutes). Arlberg Express offers a shuttle service from Zurich Airport. Lift tickets from €61 (about $94) a day. Mooser Hotel rooms from €306 ($470).

Ricky French was a guest of the Austrian National Tourist Office.

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout