Saudi travel push puts human rights in spotlight

The Arabian kingdom is investing billions of dollars in the travel sector but will western travellers want to go there?

Lounging on a carpet on the desert sands of Gharameel, I look at the stars. Locust-like insects whir, invisible. “See?” asks Rawa, my stargazing guide. “Three ladies following a coffin.” She pulls a sweater over her red T-shirt, picks up a laser pointer and traces the night air with a thin beam. The top of the coffin aligns with the North Star. “That light showed the way,” Rawa says, “for desert wanderers. My ancestors.” The three women represented by the stars, she explains, were out to avenge the death of their father, the man in the coffin. “At least,” she adds, “they are not there just for being beautiful, like many women in our folk myths.”

In daylight, northwest Saudi Arabia is the colour of persimmon. Phantasmagorical formations of eroded sandstone rear over dunes and plains that dissolve in distant heat. There is no scale here. There is only space. It is a parsed world. Alongside peerless landscapes an hour’s drive from Gharameel, the desert reveals ancient footprints. Pre-Islamic Hegra was founded by Nabateans who moved 600km south from Petra in today’s Jordan in about the first century BC to expand their empire. Across the 50ha Hegra site, archaeologists have discovered 130 tombs gouged from cliffs and excrescences.

The locusts are asleep in the midday sun, and until my guide speaks, I hear only the roaring silence of the desert. Adjohara (the name means Jewel) stops outside the tomb “of Lihyan son of Kuza”. It resembles the facade of a six-storey building, alone and proud, its elaborate, pedimented entrance dwarfed by four columns. On the top, a staircase led Lihyan to a better world. “We know this place as ‘girls’ mountain’,” says Adjohara at the Jabal Al Banat necropolis. “Out of more than 30 tombs, 26 belong to women.” The Royal Commission for AlUla (RCU), which controls Hegra, permits entrance only to this one tomb.

Women had agency in the Nabatean world. “We know this from images on coins and inscriptions talking about their legal status,” Adjohara explains. She wears thin silk gloves to protect her hands from the sun, each finger with a roll-back top, like a convertible car roof. This facilitates mobile phone usage. At Jabal Ithlib, we inspect the Diwan, the largest structure at Hegra. A man-carved cave 10m deep and 10m high, topped by a kind of monster pleated chef’s hat, the Diwan was a meeting place for the elite, with rock couches and narrow ledges for refreshments. Around the corner, Adjohara points out three lines of dot-less Kufic script on high gully walls. “Here it is clear that modern Arabic descends from Nabatean. They added dots later, to make it easier for non-Arabic peoples to differentiate between similar letters in the Koran.”

Like all desert kingdom dwellers, Nabateans were skilled hydrological engineers. Alongside a sunken tank, our driver, obeying some inner compass, withdraws across the sand and kneels to pray. Three thousand years ago, long before Muslims worshipped here or anywhere, a strategic position on the lucrative frankincense route (“like controlling the oil trade today”) drew thousands of camel caravans to Hegra. By the 2nd or 3rd century BC, AlUla, in the modern province of Medina (population: one million), had developed into a regional hub. Hegra, the major historic site of the region, thrived until it fell to the Romans in the 2nd century AD. The Nabateans, desert-dwelling master merchants, traded, besides frankincense, in peppercorns, ginger, myrrh, ebony, silk and cotton, as well as beads and glazed ceramics. Besides the north-south axis of the Arabian peninsula, traders voyaged west to Egypt.

At the dawn of the Islamic period, AlUla, which lies in the foothills of the Hijaz mountains 1000km northwest of Riyadh, found itself on the pilgrimage route from the Levant to Mecca. (Before World War I, the Ottomans built the narrow-gauge Hijaz railway on that route, and several engines loll in forgotten AlUla sidings.) Contemporary AlUla (population: 5000), also known as Wadi al-Qura (“valley of villages”) has 2.3 million date palms, as well as extensive citrus groves. Petrodollars have brought modern-day frankincense, in the form of a Harvey Nichols store in a former farmer’s mudbrick house.

Overall, the oasis showcases the first completed project in a new Saudi tourism masterplan, within which the Royal Commission, convened in 2017, specifically promotes and protects the AlUla region as Saudi’s premier heritage attraction. In the walled AlUla old town (the word was originally written Al-’Ula; the commission closed up the spelling – awkwardly, to my mind – as part of its rebranding exercise), tiny white shells twinkle in the walls of 900 closely packed and mostly roofless houses.

‘Saudi-watchers interpret both tourism and golf as an attempt at reputation-laundering. I doubt that’

Desert farmers founded the settlement in the 12th century, and their descendants worked the soil until the 1980s, when everyone shifted to the new town. The old town is now a heritage site. In a boutique hotel, a man pumps a small pair of bellows over a coal brazier on which he has set a silver-spouted dalla. Coffee etiquette decrees that he pours me half an (already tiny) cup of his cardamom-flavoured brew. “Just a little,” I am told, “so he can offer you more.”

THE FINAL FRONTIER

Does Saudi represent the final frontier of tourism? I feel perfectly comfortable, as well as safe and respected. As a woman, you can dress more or less as you want in AlUla as long as you use commonsense and avoid shorts and sleeveless tops. Head coverings are not required. The women of AlUla, or those visiting from elsewhere in Saudi, appear on the streets in a range of gear, from niqab to Gucci. Men and women mix freely in the restaurants. The mirror-clad Maraya entertainment complex, which includes a state-of-the-art 500-seater concert hall, is showing an Andy Warhol in AlUla exhibition curated by the director of Pittsburgh’s Warhol Museum. A delightful female guide shows me around, talking with gusto about the activities of Warhol’s Factory – some of its activities, anyway – and swishing her floor-length black abaya playfully against free-floating, cloud-shaped helium balloons.

That said, most Saudis dwell in permanent ethical midnight, with no guiding North Star. As long ago as 1957, British writer Jan Morris, who travelled widely in the region as a foreign correspondent, wrote, “The once proud name of Saud is becoming all but synonymous with intolerance.” The visitor must make their choice: does a holiday constitute collusion? Should one boycott a country on account of its human rights record, as dire in Saudi as it is in China, or Egypt, or Myanmar? Or will tourism turn out to be, as is naively touted, a regime-softener?

When Crown Prince Mohammed bin Salman, known as MbS, established his Royal Commission, he announced that non-religious tourism overall (not just in AlUla) will account for 10 per cent of GDP by 2030. The as-yet unbuilt centrepiece of this “Vision 2030”, the Neom resort-city on the Red Sea, is billed as “the world’s most ambitious tourism program”. The commission is controlled by the Saudi sovereign wealth fund, a multi-billion dollar investment vehicle, also known as the Public Investment Fund. This body also sponsors LIV, the golf super league that aims to establish the kingdom as a golfing destination. The recent Lionel Messi furore reveals another prong of Saudi sports outreach. The Argentinian superstar’s French team, PSG, suspended him for two weeks for making an unauthorised visit to the gulf state. (Messi is already, as of last year, a paid ambassador for Saudi tourism.) The 35-year-old was in discussions regarding a transfer to the Saudi Pro League for a reported $1.9bn two-year deal before it was reported he would play in the US.

Saudi-watchers interpret both tourism and golf as an attempt at reputation-laundering. I doubt that. If Saudi Arabia really cared what people in the West thought, it would cease criminalising homosexuals and journalist Jamal Khashoggi would still be alive. Is the regime instead planning economic diversity for the day the oil runs out? I doubt that too – the black stuff isn’t going to cease gushing any time soon. Tourism simply creates another income stream for the elite. Perhaps they hope Riyadh or even Neom might rival Dubai as a regional tourism capital. Whatever the motivation, as a participant in Saudi’s ambitious tourism experiment, today’s visitor to the AlUla oasis is presented with the one impressive taster that is actually open for business, with accommodation and historical sites accepting visitors, as well as a range of easily accessible restaurants and activities.

PAST MEETS PRESENT

As AlUla matures as a destination, luxury brands are arriving. Banyan Tree already operates a 47-villa hotel among sandstone outcrops of the Ashar Valley in the heart of the oasis (popular with the Saudi royal family, apparently), and not far off, Shaden, part of the French Accor group, is currently revamping its accommodation for next season.

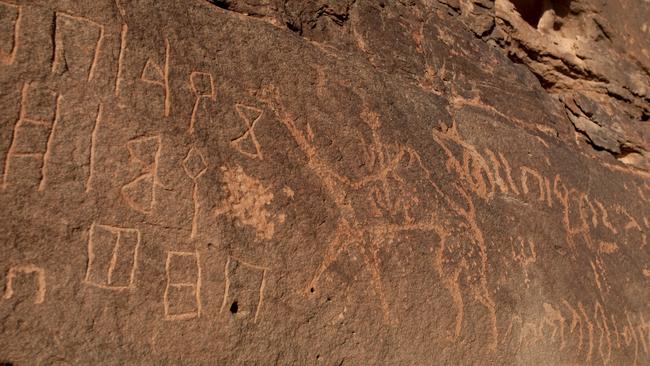

I walk one day in the oasis behind the old town (nobody stops you strolling around). The fragrance of Assyrian plum bushes wafts over gardens planted with cabbages of a blueish hue. Women, all here in burqa or niqab, sit on benches, while children play on swings suspended from palms. Close by the playgrounds and cabbages, I visit the so-called lion tombs, built 2500 years ago at Dadan, and once, before Nabateans, among the most developed independent kingdoms in northern Arabia (the Old Testament Book of Ezekiel mentions Dadan). Leonine reliefs guard a necropolis 50m above the oasis floor, the tombs entered via square-shaped holes. An archaeologist tells me he estimates just 6 per cent of the whole lost city of Dadan has been excavated. At Jabal Ikmah, a slim rocky gorge close to the site, he shows me what he calls “Nabatean Twitter”, in the form of hundreds of inscriptions carved in different alphabets.

The Habitas resort in the Ashar Valley, where I stay, consists of 96 chalet-style “pods”. Each has its own electric bike tethered outside, and mine comes with a Celestron AstroMaster 130 telescope. Up at the infinity pool, women pose for their Insta feeds in string bikinis, niqab-clad countrywomen sipping watermelon juice a few feet away – the modern equivalent of the camel-and-Cadillac shot. US-born Lita Albuquerque’s blue lady sculpture (Najma) sits cross-legged atop a rock, overseeing the bizarre proceedings below. Behind my pod, I stumble on a petroglyph of an ostrich.

Habitas’s second location in AlUla is a caravan park where 25 air-conditioned vintage Airstreams look out on to shimmering red cliffs on one side, and on the other, a Bedouin-style tent furnished with rugs and carved wooden sofas. Across the two sites, occupancy is presently 50 per cent Saudi nationals. The commission’s ambitious plans for its Nature Department include the reintroduction of the critically endangered Arabian leopard. A ranger named Bessam drives me around Sharaan, a newly created 1542sq km reserve half an hour from AlUla (Sharaan currently offers pre-booked tours only). “I come from the Black Mountains near here,” Bessam says, threading the outsized Toyota through gullies and secret waterholes before cresting a ridge. “It’s thrilling for me to see these animals and birds coming back. Sandstone is perfect for ibex, as wolves can’t climb up to eat them.” Before us, an apparently limitless vista unfurls, spiked with teetering sandstone needles.

On my last morning, I float over Hegra in a hot-air balloon. I start to see patterns in the rock. Saudi’s grand tourism plans have yet to unfold, and their realisation will be, to a certain extent, contingent on a radical improvement in the country’s human rights record. But for the first time, Western tourists can at least glimpse the proud and extraordinary past of these pre-Islamic desert kingdoms.

IN THE KNOW

British-based Trailfinders offers a Discover AlUla itinerary over four nights from £5899 ($11,100) a person twin-share, depending on season, and including international regional flights, private tour featuring accommodation at Habitas on a half-board basis, selected sightseeing and private transfers. The Australian Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade advises travellers to exercise a high degree of caution in Saudi Arabia, to avoid travelling within proximity of the border with Yemen, and to check Smart Traveller alerts and updates.

Sara Wheeler was a guest of the Royal Commission for AlUla.

TELEGRAPH MEDIA GROUP

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout