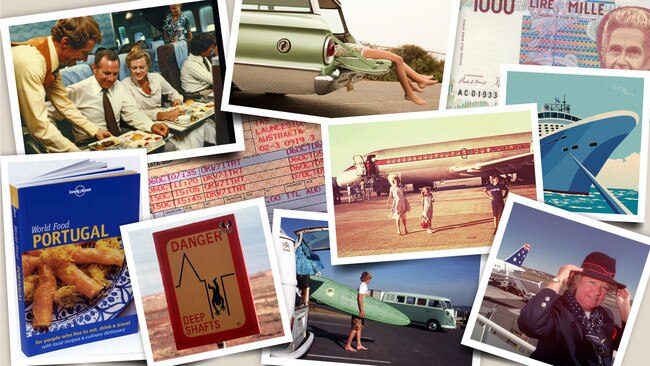

Remember passport stamps, postcards, traveller’s cheques?

From lugging thick Lonely Planet guidebooks to getting info off TikTok videos: we look back at how we travel has changed.

Overseas travel used to be the preserve of the wealthy and leisured. Phrases such as “the trip of a lifetime” meant just that for many of us. Special savings accounts were opened, plans could take years to fall into place, relatives and friends would gather at the airport to wave goodbye and weeks or even months later reassemble to welcome home these suntanned and victorious adventurers.

Invitations would be issued for slide nights so everyone could travel vicariously through our carousel of exotic lands and experiences and admire our haul of souvenirs. Now, most of us think nothing of jagging a good airfare and flying off at a moment’s notice or hitting the road for long journeys across our great southern land.

But … how the travel process has changed in terms of technology, timing, gadgetry, bureaucracy, security and expectations. Read on to discover more about the joys of nostalgia and those big, bold leaps forward.

Home and away

Pose by the Pyramids, post on social media and a posse of family, friends and followers knows exactly where you are. It wasn’t always thus. The young international traveller could go incommunicado for months with news of adventures relayed by aerogramme, the invention of Major Gumbley, a British postmaster in Iraq in 1933.

The tissue-thin, blue sheet of paper folded into its own envelope and encouraged scrunched-up handwriting to inform parents on a need-to-know basis. More elaborate tales could be told on air-mail stationery, adorned with a Par Avion sticker.

Postcards held the virtue of fewer words but pretty pictures and exotic stamps, and with luck might be delivered before the sender returned. For news from loved ones back home, we headed to the poste restante counter at a post office, where mail was held until claimed. Phone calls were for special occasions only (or a desperate plea for more money), often reverse-charged, and involved queuing at phone boxes for an expensive operator-connected and time-limited trunk call.

Pack it all in

It’s not as if printed travel guides have departed the Earth (Aussie-born Lonely Planet still does a brisk trade), but it’s almost 70 years since American Arthur Frommer held out the promise of Europe on $5 a day, later $10 (what price would grace the cover of a Frommer Guide today?) stimulating a new era of budget-conscious travel. For more sophisticated journeys, green oblong Michelin guides were the go.

Think also fold-out (but impossible to refold) maps. Giving reliable instructions to the driver could be the make-or-break of a relationship. Other essentials: phrase books; My Trip journal; a money belt to thwart the Artful Dodger. And camera equipment for photographs, maybe 8mm movies and, later, video; leave space for the Kodachrome rolls to bring home for developing, a costly exercise that made picture-taking judicious.

The mobile phone is today’s one-stop shop for recommendations, spoken directions, translations and all things pictorial. Just add a GoPro or drone.

Cash and carry

Floating the Australian dollar 40 years ago spruced up the economy, but in the days of fixed exchange rates travellers could nail costs to the cent. In the 1970s, one of our dollars bought $US1.50 (today, 64c); Levi’s 501s were bought in bulk.

Traveller’s cheques were the safe way to carry cash, often issued by Thomas Cook or American Express and usually (but not always) honoured by hotels, shops and banks.

While still available, these cheques have been in decline since the ’90s, replaced by credit and debit cards. Also sinking with the sun, bureaux de change (charging ludicrous commissions) and, indeed, cash itself. Whole trips can be taken without encountering local currencies and the challenge of quickly mastering denominations (in a bar in dim lighting).

Some cash is still advisable for, say, street markets and avoiding unpleasantness in countries (hello, USA) where tipping is non-negotiable.

Hale and hearty

For all the kerfuffle about Covid “vaccination passports”, throughout much of the 20th century a World Health Organisation-endorsed International Certificate of Vaccination or Prophylaxis, known as the “yellow card”, was necessary for entry to many countries and still is for some in Africa and South America.

Its target was curbing diseases such as cholera, typhoid, smallpox (eradicated in 1980) and yellow fever. Covid has been the travel disrupter with proof of vaccination and face masks compulsory for a time and still not uncommon, along with hand sanitisers and wipes. It has also been a wake-up call on travel insurance, once considered an essential, but which lapsed into an optional extra. The government site Smart Traveller provides up-to-date advice on countries’ health and visa requirements (unhappily, mostly gone are gloriously decorative visa stamps).

Planes, trains and automobiles

The domestic two-airlines policy kept TAA and Ansett in lockstep on fares and timetables until 1990, when competition (remember Compass?) freed up the Australian skies. Internationally, Qantas entered the jet age in 1959 with the Boeing 707, but it was the arrival in 1971 of the 747, or Jumbo, with more and cheaper seats, that carried many on their big adventures.

First class, with fine china, was there upfront, but business class (in the 1970s) and premium economy (’90s) also offered refuge from cattle class for the upwardly mobile.

Private jets, once the preserve of rock stars and billionaires, are now accessible (at a price) in group charters by operators such as Abercrombie & Kent and Captain’s Choice. Even individual private jet charters are within reach when advertised for an empty return journey after a VIP flight. Six states acting as fiefdoms (sound familiar?) and adopting three rail gauges thwarted Australia’s hope of an efficient national network.

What an eye-opener for travellers to explore Europe on Eurail passes, finding trains that were mostly reliable. And what about the Shinkansen, or Bullet Train, in Japan, operating in time for the Tokyo Olympics in 1964 and giving us the concept of “very fast” ground travel. We had the almost-glamorous Southern Aurora, with sleepers, making the Sydney-Melbourne journey, and the Sunlander from Brisbane to Cairns.

Today aspire to the luxury of the Indian-Pacific (Sydney-Perth) and The Ghan (Adelaide-Darwin), and the Venice Simplon-Orient-Express always holds international historic appeal. Let’s face it, most of our first travel experiences were in the back seat of a car as families headed off to their favourite holiday spot (there was only one).

Long hours before personal devices with only sibling squabbles for entertainment; perhaps also the car radio, but these weren’t standard fittings and how easily those aerials could be snapped by envious vandals. Travelling economically? We propped pillows against windows on overnight coaches, a Greyhound or Firefly Express perhaps, that plied the highways.

Flights of fancy

Knowledge of the “Golden Era” of flying is likely to be gained through movies, but most of us can recall when time in the air was more couth. Or perhaps we manipulate memory. Passengers dressed up to fly, even if it meant arriving at the Gold Coast in hats, tailored skirts and heels, or suits and ties.

Cabin crews were smartly attired and uniformly good-natured, and fellow travellers less inclined to inflict injury as they hoisted cabin bags overhead. We could take airline shuttle buses from downtown terminals and arrive at departure lounges with printed tickets in hand and be issued with paper boarding passes.

All still possible but, more likely, passengers have checked in online, selected seats and digitally downloaded boarding passes. While some airport operations have become service-lite, security has intensified and become more hands-on with pat downs, metal detectors, luggage X-rays and swipes for explosives, the outcome of hijacks in the 1960-70s, bombings (Lockerbie, 1988) and, of course, September 11.

In-flight meals now seem more modest, and often at cost, but there was a time when menus took no account of “dietaries” (vegetarian, gluten-free) and entertainment was one film on screens that descended from above; no self-start film, TV and music collections, podcasts and games. Lights burning into the night as passengers devour airport novels are now rare, but thankfully no more cigarettes light up. The greatest invention? Let’s say suitcases with wheels and baggage tracking devices.

Location, location, location

Before gap years, young people tended to finish their education, work and save for a few years then head overseas, often to London where they lived the Barry McKenzie-like dream of a bedsit (no refrigerator but with a cash-hungry heater) in Earls Court, working in the West End theatre (ushering and checking handbags for IRA bombs), buying a Kombi from the motley selection circling Australia House on The Strand and touring Britain and the Continent. Throw in a Contiki tour. But the world has never been entirely our oyster.

Parts of Southeast Asia, now popular destinations, were war-torn, and some countries in Africa and South America prone to rebellion. Our interests tended to be guidebook sights, so yet to come were expedition tourism (although national park hikes were popular), cultural tours and wellness retreats.

Food can now frame a whole holiday with dining, markets and cooking experiences. We may well follow an itinerary we’ve enjoyed on a celebrity chef’s TV show or seek out the adventurous street-food choices of YouTube vloggers. For many, the top priority was to travel OS; we’d discover our own backyard later. That “later” came with Covid when the door to the world shut. We’ve found much to love in our regions, and the growth of indigenous and environmental tourism confirms there’s no place like home.

You must remember this

How did we rekindle treasured moments? We filled shelves with ornaments (windmills and Tudor houses), snow globes and dolls in national costumes.

We displayed souvenir ashtrays and matchbooks. We nurtured stamp and coin collections, photo albums and autograph books, and kept addresses of our new best friends (especially those we might stay with).

Tea towels, T-shirts, fridge magnets, posters for framing, egg cups and Toby Jugs; these were a few of our favourite things. A special call-out to slide nights and stealing a glance at how many boxes of Kodak 36s had still to be loaded in a cartridge for projection.

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout