Pompeii, Acropolis, Delphi, Assos, Jerash, and the joy of ancient ruins

Beauty, architecture, solemnity and a vivid experience of history await you at the world’s most amazing ancient ruins.

Here are nine of the most beautiful ancient sites to visit — and one you sadly cannot.

The Vesuvian cities, Campania, southern Italy. Pompeii is the quintessential dead city. This bustling provincial town was preserved by the eruption of nearby Vesuvius in AD79 and for as long as Pompeii stands it will serve as a memento mori. The frescoed walls are stunning, particularly the scarlet-hued Villa of the Mysteries. Pompeii is best seen as a combo with nearby Herculaneum, which was fried by an intense wave of heat before being swallowed whole by pyroclastic lava. As a consequence the second floors, in some cases, survive. Herculaneum was a seaside town, further up the social scale than Pompeii, and one of its lavish villas housed a philosopher’s library — some of the charred scrolls are preserved at the National Library of Naples.

Agrigento, Sicily. The honey-hued Doric Temple of Concordia is the centrepiece of the so-called valley of the temples and it is one of the finest surviving structures from the world of Greater Greece, or Magna Graecia. But the entire site, commanding fine views of the Mediterranean, is a providential gift. It’s from across this sea that Agrigento’s destroyers, the Carthaginians, came in 406BC. The flourishing city never recovered.

Assos, Turkey. Not much of the 6th century BC Temple of Athena at Assos remains, just a few Doric columns with their fluting worn by the passage of time. What makes a visit to this humble site in western Turkey memorable, aside from its ancient provenance, is the view from 1200m above the Aegean to the Greek island of Lesbos and beyond. When you look out to the peaks of Lesbos on a bright day, across the Aegean with its sheen of crushed glass, you see the world as the ancients did.

Jerash, Jordan. Easily accessible from Amman, this miraculously well-preserved Hellenistic city (likely founded by Alexander of Macedon) was rebuilt on a Roman plan and among its glories are a circular forum with a colonnade in the Ionic order wrapped perfectly around it, an arch erected to the Emperor Hadrian in the early 2nd century and a main street flanked by Corinthian columns. It’s referred to as the Pompeii of the Middle East, or the Rome, but it possesses neither the melancholy of the former nor the majesty of the latter. Jerash is its own thing: a well-appointed outpost of Roman power that retains many of the grace notes — baths, theatre, hippodrome, beautifully worked stone, lovely mosaics — of the ancient art of life.

Acropolis, Greece. It has the deepest historical and artistic significance of any site on this list: the taproot of Western culture, no less, although obviously some of its exquisite Parthenon sculptures — among the great artworks from any age — are elsewhere. The Acropolis, or high city, is a complex composed of the 5th century BC Parthenon and the Erechtheion (named for the mythological founder of Athens) flanked with its famed caryatids, and other lesser shrines.

If you feel a sense of nerve-tingling solemnity as you enter the complex through the Propylaia, that’s as it should be: this is the sanctuary of an Olympian deity. A massive gold and ivory statue of the goddess Athena, in her guise as a virgin (“parthenos”) once stood at the heart of the structure: the cella. It is at once a religious precinct and a celebration of the Athenian triumph over Persia in 479BC, 40 years before work on the Parthenon began. In antiquity the place was a riot of colour and the air reeked with the stench of animal sacrifice.

Ephesus, Turkey. An Aegean city whose roots are Greek, Ephesus rose over the centuries to rival Rome. Beautifully preserved and lovingly restored, the double-storey facade of the Library of Celsus, once a pile of rubble, is a triumph of classical cosmetic archeology. As a stop on St Paul’s evangelical mission, Ephesus serves as a bridge to 1st century Christianity and remains a place of religious pilgrimage 2000 years later. In high season be sure to arrive early as the tsunami of tour groups can batter the independent traveller.

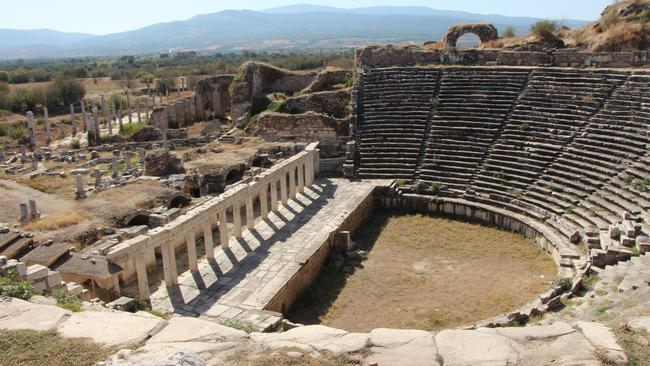

Aphrodisias, Turkey. A joy to behold, Aphrodisias is nestled in a rural landscape inland from Turkey’s western coast, with a blue-green mountain range as a backdrop. It may be the most beautiful ruin of all, which is fitting as the town was consecrated to the love goddess Aphrodite, and she was never less than easy on the eye. The site’s architectural emblem is its monumental tetrapylon gate. Made up of four clusters of four columns, some with spiral fluting, it is partially restored. The city was founded near a quarry of fine marble and in antiquity it was famous as a producer of high-quality statuary. Owing to its isolation and late rediscovery — serious excavation didn’t begin until the 1960s — Aphrodisias preserves a remarkable number of sculptures, carved panels and inscriptions. Time dissolves at lovely Aphrodisias.

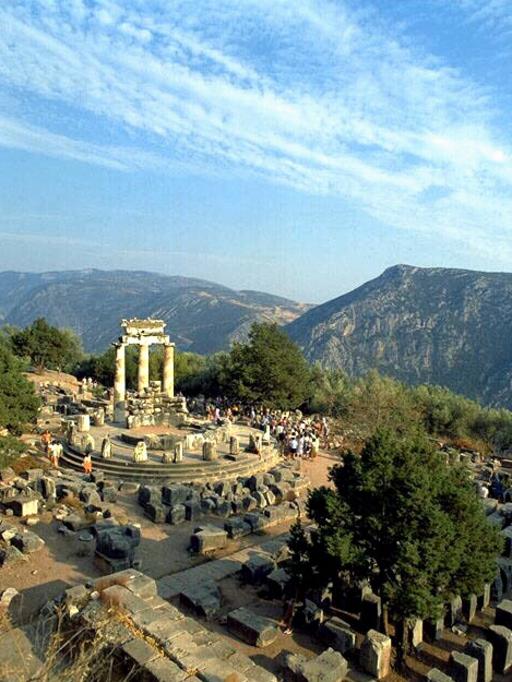

Delphi, Greece. Clinging to Mount Parnassus, cascading in terraces down its wooded slope, are the sacred ruins of Delphi. Within this mountain sanctuary stands the 4th century temple of Apollo. Son of Zeus by Leto, Apollo was the presiding deity here and slayer of the primal serpent Pytho. Delphi was the omphalos, or naval stone — from the 6th century BC the spiritual centre of the world — and rulers from across the Mediterranean sent envoys to consult its riddle-speaking oracle.

Delphi doesn’t disappoint. Winding around the terraces you come across a theatre overlooking the spiritually charged landscape, as well as the reconstructed Treasury of Athens, a stadium that recalls the Pythian games (remember the Pytho) held every four years, and the remains of a circular temple to Athena. When it’s time to come out of the weather — it’s snowy in winter, sunbaked in summer — head for the archeological museum for a glimpse of Delphi’s famed charioteer with the spooky eyes. He is one of the few complete bronzes to survive from antiquity — most were melted, leaving us with marble copies.

Epidaurus, Greece. The theatres of classical antiquity have done pretty well in the struggle against time. The 4th century BC theatre of Epidaurus, designed to seat 14,000, is one of the largest and most beautiful. It is missing its stage apparatus but the views across the hills of the eastern Peloponnese are wonderful. And something elevating this theatre above others is its location as the hub of a sanctuary to the god of healing, Asclepius. This was an important pilgrim site in antiquity — a kind of vast pagan clinic. At the museum you can learn everything about physical and psychic health in the centuries before Christ.

Palmyra, Syria. Coming to Palmyra in the late afternoon, as the sun’s last rays drape the Syrian desert, the ancient caravan city’s roseate colonnade with its Corinthian capitals is all aglow. Palmyra, an oasis of palms, as its name suggests, is magical. Under its 3rd century queen, Zenobia, it rose to challenge Rome. The rebellion was put down and the proud Zenobia taken to Rome in chains, where she likely met her end. Her legend adds to Palmyra’s allure. Despite the recent destruction of the Baal Shamin temple and the continuing presence of Islamic State in what was Syria’s premier tourist attraction, Palmyra is included here as a small act of resistance.

There is reason for hope. Few of the standing columns in the great surviving sites from classical antiquity have not, at some stage, been piles of column drums buried by sand or garlanded with weeds; many still are. The Library of Celsus at Ephesus stands upright courtesy of a few modern crutches. The Parthenon itself has had its share of misadventure — including a hit from a mortar shell in 1687. Palmyra will surely rise again.

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout