Memories of Madagascar, land of the lemurs

Madagascar’s unique cultures and dazzling biodiversity make it an unforgettable destination.

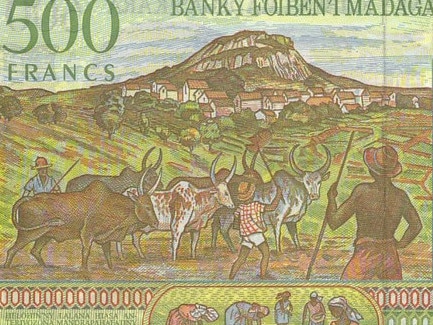

Tucked away in my writing desk there’s a crumpled banknote that’s probably the most powerful souvenir I own. The note is pale green. On one side is a traveller’s palm tree and a portrait of a woman with plaited hair, but it’s the flip side that takes me back to Madagascar in a second. It’s a village scene, simply drawn but rich in detail, dominated by a rocky hilltop piercing the sky. Houses cluster at its base above a tree-filled, terraced valley scored with red volcanic soil. In the foreground, three herdsmen in hats guard a mob of majestic-horned zebu cattle.

The scene is so vivid to me, even now, because I have been to this place and marvelled at it with my own eyes. Halfway through a 10-day road-trip across the world’s fourth-largest island, my driver, Andry, stopped at this exact spot and suggested I take a photo. As I got the camera ready he pulled a 500-franc note from his wallet and unfolded it between my eyes and the view beyond. Same, same.

It’s a memory I cherish as much for its novelty as for Andry’s thoughtfulness in taking me to see one of his country’s lesser-known landmarks. I don’t know the name of the village; I thought I’d written it down but now suspect the Malagasy words in my journal mean “five hundred”. So let’s call it the 500 Village.

Four-wheel drives and foreigners are rare sights in rural Madagascar and I remember children surging down the hill to greet us. And later chasing our vehicle down the muddy red road as we departed, squealing with joy and taking turns to shake my hand.

At this point we have been five days on the road, covered 1674km, and I am still no closer to comprehending Madagascar. It is a country that doesn’t look, feel or sound like anywhere else I’ve been. Its vastness, unique cultures, dazzling biodiversity (about 90 per cent of plant and animals species are endemic) and, yes, its poverty leave me dumbstruck as we continue our odyssey.

Andry often turns to study my face and ask, “Do you like this country?”. I’ve rarely been so exhilarated by a place but struggle to find the right words in French to describe its stunning novelty. Madagascar is the size of France so there’s only so much you can see in 10 days. You need to choose your targets. Mine are the national parks; I want to experience what it’s like being completely surrounded by plants and animals found nowhere else on Earth. Amazingly, in the decade from 1999 to 2010, Madagascar added 615 new species to global taxonomy, including more than 40 mammals and 60 reptiles.

At Ranomafana National Park, I brave the threat of malaria to clamber through humid, intensely buggy rainforests in search of prosimians, our earliest ancestors. These primitive primates, marooned on Madagascar when it broke away from mainland Africa about 160 million years ago, never evolved into monkeys and apes. Lemurs are found only on this Indian Ocean island. There are about 110 species left; almost all are critically endangered. As we head deep into the forest, guide Mami shows me the world’s tiniest chameleon hiding under a leaf, a weird giraffe-necked weevil and, eventually, my first lemurs. We spot a pair of bamboo or gentle lemurs, which look like badly drawn cats, foraging on the floor and later a family of three Milne-Edwards sifaka, including a four-month-old baby on its mother’s back, swinging through the trees like mini-Tarzans.

At Isalo National Park there is no rainforest, only a desert-like expanse of grasslands, oases and fabulous rock formations with names such as “crocodile emerging from the water” and “the chameleon and the tortoise’’. It’s a landscape to inspire wild imagination.

From my balcony at Motel de l’Isalo, gazing across broad yellow plains planted with palms and aloe, I fully expect a stegosaurus to lumber into view at any moment. Instead, there are only wild goats and the occasional Bara cowherd. This land is sacred to the Bara people, who bury their dead in caskets studded with coins for the afterlife and place these in caves high up on the rock faces. The higher the tomb, the closer to god.

Between national parks, we visit cities such as Fianarantsoa, a handsome 19th-century hilltop settlement where the houses have steep roofs and planter boxes and schoolchildren shadow me in the streets calling out, “Bonjour, vazaha!”. Hello, white man!

Andry is incredibly patient with my novelty. Wherever we stop, a crowd of amateur anthropologists gathers to witness the foreigner, observe his dress and mannerisms, and shout at him in French or Malagasy.

A group of Betsileo people see our vehicle parked by the road and come to investigate. The male leader is grinning widely with his remaining teeth. He draws close and yells something at me in Malagasy, the confusion on my face only encouraging him to increase the volume. Andry laughs at the bizarre scene, and then the man starts laughing, and then we’re all laughing like lunatics, no common language necessary.

Very occasionally I manage to convince Andry to let me eat at a simple “hotely”, a roadside diner of questionable hygiene and limited menu. At one I order a “soupe Chinoise” with no meat, s’il-vous plait, that nevertheless arrives with sickly grey bits floating about a clump of noodles. I palm it off to two street urchins who shovel the greasy mess into their mouths and thank me enthusiastically afterwards. Haute cuisine is a relative concept.

Every grand adventure needs a dramatic climax and ours comes at Perinet reserve, officially the Andasibe-Mantadia National Park, about three hours’ drive south of the capital, Antananarivo. The park is home to many unique animals including 11 lemur species, but there I’m really only interested in the indri, the largest living lemur. It survives only in a few patches of primary forest in the central highlands and dies in captivity, a fact that makes this shrinking habitat seem all the more precious.

I stay at the Feon’ny Ala (Voice of the Forest) guesthouse in a simple A-frame bungalow. There’s little to recommend the place aside from the resident dwarf lemur in the palm tree outside the restaurant, and its location. Guests — all except me dressed like Raiders of the Lost Ark in breathable beige and variations on the pith helmet — sleep in the same jungle as the indri. At 5am, I’m woken by the most alarming call, like a cross between whale song and a siren, sad but urgent. Two hours later, after a mad scramble into the dark, damp heart of the forest, I’m standing below a towering tree where a family of five indri clusters in its highest branches. We’re swarmed by bugs, drenched by rain, waiting for the show to begin when a plaintive, resounding boom floods every space in the forest.

The territorial cry is designed to be heard up to 4km away; at such close quarters it reverberates in my rib cage. One moment I’m feeling terrified, the next profoundly sad. But as other family groups begin responding in the distance, the cries from our indris become louder and more preposterous, and suddenly I’m laughing so hard I’m gasping for air, tears merging with the rainwater streaming down my face. It’s a joyous, ecstatic, unforgettable encounter.

On the drive back to Tana, Andry turns to me and asks, one final time, “Do you like this country?”. I look at him in disbelief and we both break into grins. He knows the answer well by now.

-

IN THE KNOW

GO May to October is high season, before the rains come (including cyclones between January and March). Take warm clothing if spending any time in the cool highlands.

STAY Hotel Colbert has 109 rooms and eight suites, three restaurants, a spa and poker machines, and a winning location in the smart upper town of Antananarivo; hotel-restaurant-colbert.com.

PLAN Book a customised itinerary via email with Transcontinents, which has been organising travellers’ adventures across Madagascar since the 1950s; transcontinents.mg.

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout